Michael Stipe pops his head around a pillar. “Hello! It’s Michael!” he says, though we’ve met before and he’s very famous. It’s early evening and we’re in the lobby of Stipe’s London hotel, two minutes’ walk from the Extinction Rebellion protest in Trafalgar Square. All is shiny, stately and calm, though we can hear the occasional police helicopter above our heads. This pleases Stipe. He’s a supporter of the protest; in fact he’s just released his first solo single, Your Capricious Soul, with a pay-as-much-as-you-like price tag, all monies going to Extinction Rebellion.

“I mean,” he says, “I came into London today, and I can’t think of a better excuse to be late for a meeting than a bunch of people who are literally looking at the end of us – and we’re taking a bunch of species with us if we go – and trying to do something about it … Oh! Have one of these!” He digs into his bag and gives me his own specially designed XR sticker.

We take the stairs to his suite – “I asked for a small room,” he says, laughing at himself, “but they insisted” – where Stipe fiddles expertly with the coffee machine and shows me how he likes to slice a pear. “You cut it like this, and then you can stand the core up on a plate, like a column. Then you photograph it from all sides and animate the images, so it looks like the column is spinning,” he says.

Stipe, as you can tell, is not your usual pop star. In fact, he’s not really a pop star at all these days, though he’s working on solo material, occasionally produces other bands, such as Fischerspooner, and is still best known as the singer in REM. Now 59, slight and neat, he has the hard-to-pin-down feel of a much younger person. There’s no weight about him, no sense of him becoming settled in his ways. Instead, he reminds me of a curious faun: skittery, friendly, interested but naturally shy. He’s a talker, but he’s not dominant; he doesn’t swamp you with big ego charisma, though he’s utterly charming. How astonishing that he became so famous, I think. You wouldn’t imagine he’d be able to bear it, despite his ease in a suite. Instead of a lead singer, Stipe has the air of an artist, regarding the world from unusual angles.

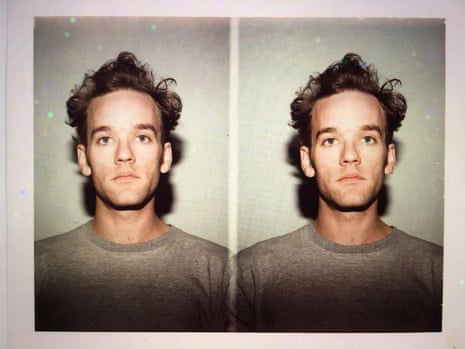

And actually, since REM split, in 2011, Stipe has been just this, making installations and video work, sculpture and photography. He filmed his first artistic mentor, Jeremy Ayers, dancing for seven minutes, then set it to house music composed on a Moog. He makes books and experimental sculptures in his studio in New York, where he lives with his long-term partner, Thomas (pronounced Tohma) Dozol, who’s also a photographer. In fact, in the years since REM, Stipe has been quite at ease with exploring his art, with not performing. “It feels like the real me,” he says. “I’m working in all these different mediums and it makes sense.” At one point he grew the most enormous wild man beard, though it’s trimmed short today. He wears a green polo shirt, jeans, green socks and a beautiful large gold ring on his left hand.

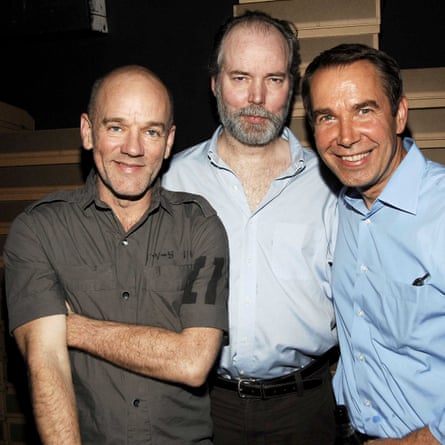

Stipe is in London as part of a short promotional tour, with a double set of duties. It’s the 25th anniversary of REM’s Monster, and there’s a special box set coming out, so he’s been chatting about that to journalists, alongside REM musicians Peter Buck and Mike Mills. Separately, he’s also here to discuss his new book of photographs, the second in a series made in collaboration with other people. The first, Volume 1, came out last year: it featured just 35 photographs and was made with artist/curator Jonathan Berger. The second, Our Interference Times: A Visual Record, with writer Douglas Coupland, has just been published. And it’s Interference Times that we’re here to contemplate. We put the book on the table, open it at page one… “A window,” says Stipe. “In black and white. And kind of shitty, like a shitty cellphone picture. Every image after this is colour, like boom, here we are in real life. Or fantasy life. It’s basically the mind of Michael.”

Our Interference Times is a far weightier tome than Volume 1, and has a different tone. Volume 1 played with ideas of celebrity, intimacy and family, showcasing snaps of a young River Phoenix in the back of a car, of Kurt Cobain’s hands. There were also a couple of pictures, not taken by Stipe, but owned by him, of James Dean, of Marilyn Monroe as a baby, and an outrageous Esquire dinner party at the former New York nightclub Studio 54 featuring Andy Warhol and Donald Trump. I interviewed Stipe onstage at the ICA about Volume 1 last year: we noted that few of the portraits showed people looking straight at the camera. Stipe is too offbeat, too wary for that.

The new book is less densely populated, though there are pictures of people, and those without humans show evidence of our interference with nature’s design. Stipe talks about one, which seems to be there to deliberately annoy neat freaks. It’s a picture of a manhole cover, a pavement and a fence. None of them fit together properly. It’s maddening … though Stipe sees it differently.

“You have these striations from a natural material, made into concrete,” he says. “You have these stones laid out as a mosaic, a manhole cover. And then a tree that’s been cut into slabs. It’s man attempting to create order from chaos. A lot of the book is really about that old waltz between man and nature.”

Actually, there are a lot of regimented grids in the book, though these are often out of whack, or they’re details of something that you can’t quite work out, that you think is something different. On more than one occasion, you find yourself turning your head, wondering: What IS that?, until you see. Photographs are laid out to play off each other, with one almost chatting to its facing companion. For instance, here’s a photograph of a naked, painted man… “I painted him,” says Stipe. “I took the picture from on top of a ladder, he’s lying on the studio floor. I turned it upside down, so he looks like Icarus falling from the sky.” Opposite this floating, delicate figure is a shot of a heavy marble statue of Hermes fastening his sandal, which Stipe saw in Versailles. The contrast between the fluidity and solidity enhances both.

Often what Stipe and Coupland, who are old friends, were interested in – especially Stipe – is the interaction between our old analogue lives and our new digital ones. There are many photographs of photographs: mobile-phone snaps of a computer screen displaying an older picture created with a film camera. Stipe is fascinated with how this doesn’t really work, how the different media don’t talk to each other very well, even though they’re essentially doing the same thing. The pixels shudder, the focus is kaput. He’s interested in how the past and future are overlapping, but ineptly, inelegantly. Does this mean that the past was better? After all, this is a book he’s promoting, not a computer game, and one for which he spent a lot of time getting the details right. He wanted the images to bleed right out to the edges, he wanted the pages to only be numbered once in every five. When I mention that I love how the book smells (like old books), he’s really chuffed: he was careful to choose a particular ink, with a particularly pleasing aroma. “I like that the book is an artefact,” he says. “Ten years ago, I did a whole series of pieces about books, because we all thought that books were going away and we’d all be looking at everything backlit from now on. But we were wrong.”

One of the shots is of his lyrics to Hope, from Up, and Stipe mentions that the song is about a man trying to save his own life by turning to a seemingly ridiculous experimental medical procedure (injecting himself with alligator DNA). He connects it to this same analogue-meets-digital feeling.

“This weird 30-year period that we’re in,” he says. “Actually, I think it’s going to be 40 years – until the next shoe drops, when it’s like: ‘Holy fuck, where are we?’ The next shoe dropping will be something mad like a world leader announcing: ‘Yes, in fact we are living among aliens, or they are living among us. And we’ve known it for 80 years and we didn’t tell you because we thought it would freak you out.’ Or, the next shoe dropping is another Fukushima, but on a grander scale. Or it’s that medical research advances so quickly that suddenly there’s a cure for everything, but you have to be a billionaire to be able to afford it.”

What he means, I think, is that the future is amazing and terrifying, and almost upon us: how are we dealing with it? How is it changing us? He wonders about social media. He used to post pictures on Instagram, and there was a time when he’d put up selfies taken with famous people, but cut the other famous person out of frame, just leaving himself, grinning like a loon. “Yes, cutting Salman Rushdie’s face in half, or Patti Smith, or Tilda Swinton or Sofia Coppola. With me laughing or smiling in that centre. I thought it was funny.” He’s stopped now, moved his Instagram to private, and has no Twitter presence at all. At one point last year, his website was just a series of mad moving images, though now it’s promoting Your Capricious Soul.

He’s not frightened of the future; he’s just interested.

“Visually, with digital technology we’re actually coming closer to nature,” he says, “If you look at anything natural under a microscope, it breaks down into fractals. And we are now looking at the world in fractals, through pixels, rather than a halftone, which is how we used to see images with print.”

Stipe has taken thousands of photographs in his time: about 37,000, he thinks, kept in “a house” and in storage facilities. He’s a massive hoarder (when he puts on a jumper later, he mentions that it’s one that he bought in the 1990s, and found the other day when going through a storage container), and he started photography young, taking a course when he was 13, then studying photography and painting at the University of Georgia before leaving to form REM. And he often used his training and art sensibilities while in the band – directing videos, overlooking graphics and stage design. His photographs became LP covers, and he used his camera as a diary when touring. Despite all this, he says that he would have preferred to have been a fine artist, but he doesn’t like his drawing line. In Our Interference Times, there’s some of his drawing near the front – a profile, drawn when he was very young, some school work, a copy of some graphic writing. “I liked how it looked, which is very unusual for me,” he says. There’s also a picture of a smashed lightbulb, representing an incident that happened when Stipe was three years old.

“I bit into a lightbulb because I wanted to be the filament,” he says. “And the only way that I knew to get inside was to bite through. So I did. My father and my uncle got the glass out of my mouth, they got some glue, and they put the lightbulb back together to make sure I hadn’t swallowed any glass. I distinctly remember doing it. The desire to be the filament…”

To become the light? I say. That’s an easy metaphor.

“Well, I was a year out of scarlet fever,” says Stipe. “I had scarlet fever as a two-year-old and it boils your brain. You use your synapses differently. And that’s become part of my mythology of myself, and I go along with it. I do think differently and I know that. I’m neither synesthetic nor on the spectrum, but there are similarities. I talk differently, I know!”

Stipe’s phone buzzes: his friends, fashion designer Erdem and Erdem’s sister, Sara, a documentary maker, are in the lobby. They’re going for dinner, but Stipe has something he wants to say first.

“I’m worried about people that are trying to eliminate or delete or get rid of the mistakes,” he says. “It’s like, no, no, no wait, that’s where brilliance lives. That’s where instinct lives. That’s where God lives. That’s the spark. You know, when the book was printed, I looked at it, and I got halfway through and I was like: ‘This is such a weird book. It’s so weird.’ I’d thought, as I used to do with my lyric writing, I thought I was being so clear and so obvious and actually overstating my points. Overdoing it, really. But actually, the book is weird. It might take a bit of work, but I feel like if you go from beginning to end and you close the book, you might look up and see something a little bit differently than you had before.”

Stipe puts on a beanie hat, and his 90s jumper, and we go down to the lobby. He wants to check on the Extinction Rebellion protest before dinner. Erdem is a bit worried – he doesn’t like crowds, in case they turn nasty – but we all walk to Trafalgar Square, to wander between the tents and the flags, to dart through the crowd around an anarcho-rap band, the people queuing for vegan curry. It’s like the Green Fields at Glastonbury. And Stipe is utterly at home, moving swiftly between everyone, always looking, never stopping. I leave him there, in the dark, completely happy.

Our Interference Times: A Visual Record by Michael Stipe with Douglas Coupland is published by Damiani (£45). Michael Stipe’s Your Capricious Soul is available to download now