The Military Origins of Layering

The popular way to keep warm outdoors owes a debt to World War II–era clothing science. An Object Lesson.

I used to think of layering as a timeless concept. The idea of wearing many light articles of clothing rather than a few heavy ones was everywhere: my brother’s Boys’ Life magazines, advertisements from my local outdoors store, my summer camp’s suggested packing list. But, like any way of dressing, layering had to be invented.

In his 2005 memoir, Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia, claimed that his outdoor-clothing company, founded in 1973, was the first to bring the concept to the outdoors community. But the idea goes back further than that. Almost every American’s understanding of layering comes from the mid-century U.S. military.

In 1943, the Quartermaster Corps—the branch of the U.S. Army charged with procuring uniforms, among many other essential logistics of war—introduced an experimental new uniform kit, which it named the M-43. The ensemble included a woolen undershirt, a long-sleeved, flannel shirt, and a sweater. But the star of the kit was a new field jacket, which was (somewhat confusingly) also called the M-43—a nine-ounce, tightly woven cotton sateen garment, drab olive in color, sporting big pockets on the chest and at the hips.

Today, Americans need look no further than cotton T-shirts, cargo shorts, and camouflage to see how military styling has entered everyday life. But the M-43 jacket was not just a style. It also taught an idea to millions of Americans. Just as the military jeep brought four-wheel drive to the masses, so the M-43 made layering a civilian staple.

The designers intended the jacket to be used as the outer shell in different climates around the world—global outerwear for global war. In extreme cold, a soldier would pair the M-43 with multiple thin layers underneath. In warmer climates, he (the jacket was designed for men’s bodies) could keep the outer shell but peel off the other layers.

The military did not invent layering. In the 19th century, home economists published research on managing body temperature, which in turn depended on understandings of dress that dated to centuries earlier. In just one example of nascent clothing science, Charlotte Gibbs argued in 1912 that “several layers of lightweight material are better than one layer of thick material.”

Even though it didn’t create the concept, the Quartermaster Corps sought to build an R&D program to transform clothing into a technology. A former Harvard Business School professor, Georges Doriot, took charge of the Harvard Fatigue Lab research units that were modeled after the male-dominated field of industrial hygiene—the study of the body at work. Doriot considered the layers of the M-43 uniform to be as important as weapons and battle tactics to America’s military success. “The greatest enemy, besides what we normally call the enemy, is nature,” he explained during a 1946 congressional hearing.

The military tested the new clothing assembly that would confront this natural enemy in a series of specialized research facilities, including the Cold Chamber, a 16-by-32-foot refrigerated room with a two-person treadmill and a snow machine. Military scientists adjusted temperatures, wind velocity, and treadmill speed to assess their effects on volunteer test subjects. One day, soldiers might be dressed in furs and mukluks as the scientists looked on through a large glass window. The next, the test subjects might be clad only in underwear in the cold. The soldiers’ skin temperatures, measured via sensors attached to various parts of their bodies, helped scientists assess the effectiveness of the outfits.

A Desert Chamber and a Jungle Chamber used similar techniques to measure the performance of clothing and bodies in extreme heat and humidity. Doriot’s team also tested new ideas about uniforms with a human-size metal mannequin that it called the “Copper Man.” Like the human test subjects on the Cold Chamber treadmill, the mannequin might be dressed in any number of layers. He had heating elements inside so that his “skin” would mimic that of a human. Since he couldn’t speak for himself, thermocouples relayed data about changes in his “skin” temperature as his outfits changed. All of this research helped Doriot’s team understand how layers worked to trap air and prevent the loss of body heat, and these insights informed the design of the M-43.

Military research reports—available in Doriot’s papers at the Library of Congress—confirmed that the jacket and its accompanying layers kept soldiers warm in weather as cold as 0 degrees Fahrenheit. The reports also suggested that the jacket system worked well in the rain. Moreover, the tight weave of its cotton fabric meant that it kept out cold blasts of air on windy days.

But convincing other military officials and soldiers of its benefits took a concerted effort. For the M-43 layering system to work, soldiers had to know how to use it. So military experts developed a layering-education curriculum, which shows how the M-43 became both a popular style and a model for dressing according to scientific principles. During one 90-minute indoctrination class, soldiers listened to a lecture on how to stay alive in the cold and watched a demonstration of how to wear and adjust each item in the M-43 uniform assembly.

In interviews conducted by the Quartermaster Corps, soldiers during the war said they liked the M-43, but not always for the reasons the scientists had expected they would. The soldiers cared as much about the look of the jacket as they did about its practical details, such as the length and pocket space. One soldier said, “This uniform makes us feel like soldiers. The old one didn’t.”

Layering was familiar to outdoors enthusiasts long before Yvon Chouinard and Patagonia came along in the 1970s. In fact, earlier outdoor-industry professionals played an important role in proliferating the layering principle. L. L. Bean, Eddie Bauer, and Harold Hirsch (of Hirsch-Weis and its skiwear brand, White Stag) were among the many civilians who worked as wartime consultants on equipment and clothing design. After the war, they brought design innovations and clothing-science concepts from military research to civilian product lines at their eponymous companies. White Stag’s advertising campaigns, for example, proudly pointed to the military origins of its new civilian styles. The 1943 4-Season “Off-Duty” Jacket, featuring the big pockets and loose fit of the M-43—a “leisure jacket gone military!”—not only capitalized on the cachet of association with a victorious army, but also continued to spread the Army’s lessons on the science of dress to everyday American life.

Hirsch reflected on the original olive jacket as a versatile and technically sophisticated innovation during an interview in the late ’80s, near the end of his life: “The soldier could be more active, more mobile, with light weight clothing” such as the M-43, he said.

Walk into a research facility at an outdoor-clothing manufacturer today, and you will find modern versions of the Cold Chamber and the Copper Man. Similarly, military R&D labs still rely on approaches to studying clothing and human bodies that were developed during World War II.

The arrival of synthetic materials such as nylon further improved the function of layered clothing in wet, cold conditions. Gore-Tex, a waterproof and breathable synthetic laminate that hit the consumer market in 1976, offered what some considered a better alternative to cotton. But new fabrics and fibers only update the materials; the layering principle popularized by military science remains.

The military shaped Americans’ sense of style in other ways, too. After demobilization, the historian Paul Fussell explains, veterans who had gotten used to “loose, highly informal” uniforms were primed to keep shifting men’s fashion toward casual wear. Out were the “trim fit and exaggerated shoulders” of the prewar period. Looking prepared to get one’s hands dirty, as a soldier might in an M-43 jacket, became more important than a tailored appearance.

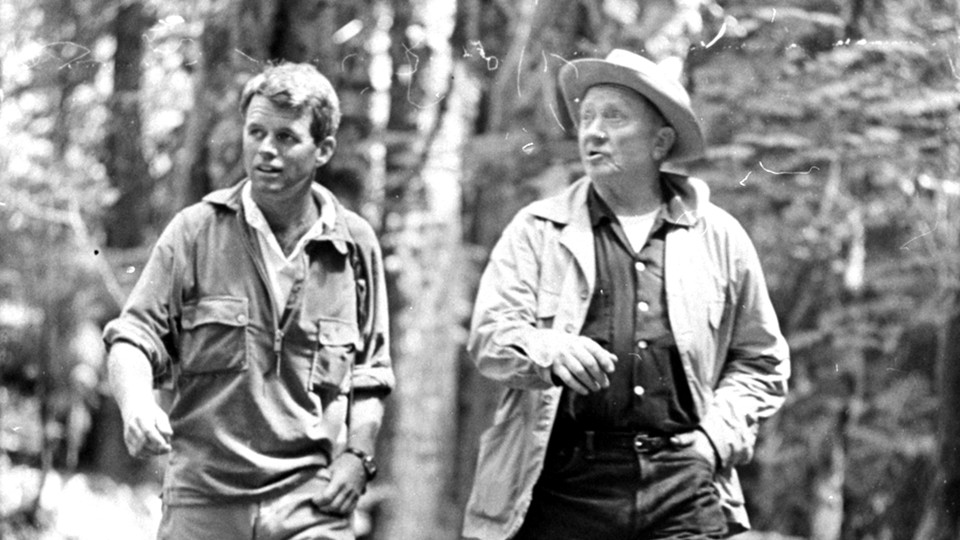

But the field jacket wasn’t a static symbol. In the 1960s and ’70s, for instance, antiwar protesters adopted a redesigned field jacket. On their bodies, the jacket questioned how masculinity and ideology might have led to the catastrophe unfolding in Vietnam. At the same time, outdoor recreationists were flocking to military-surplus stores to buy field jackets as a relatively affordable piece of their excursion ensembles.

Their faith in the layering system was not inevitable. In World War II, every American general and combat soldier thought he was an expert on how to dress. If you’ve been hunting, or have a favorite type of shoe, “you think you know all about it,” Doriot explained to Congress in 1946. His research laboratories and education programs converted die-hard wool fans on the military front into layering’s early adopters. Without him, civilians might never have come to believe that layering was a natural ally in the war against the cold.

This post appears courtesy of Object Lessons.