Before the NFL begins its 100th season on Thursday, Meek Mill and Meghan Trainor will perform a free show in Chicago’s Grant Park before the Bears take on the Green Bay Packers. It is the first event for Jay-Z and Roc Nation’s eyebrow-raising partnership with the league, but it’s nowhere close to being the most controversial kickoff concert in NFL history. That honor belongs to a quaint little soirée known as “NFL Kickoff Live 2003 From the National Mall Presented by Pepsi Vanilla,” after which Congress passed legislation to ensure nothing like it would ever happen again.

The NFL didn’t feature a stand-alone opening game until 2002, when then-Commissioner Paul Tagliabue and league officials convinced the city of New York to let them organize a Bon Jovi–headlined pregame concert in Times Square. It was advertised as “the world’s largest tailgate party” and framed as an economic boost for local businesses suffering in the wake of 9/11. “They really wanted to show the country, and the world, that New York City is back,” John Collins, the NFL’s head of marketing said. The event also worked as a stimulus package for the NFL: Ratings of that Thursday night game went up 11 percent from the previous season’s opening Sunday slate.

In keeping with the post-9/11 response theme, the NFL chose D.C. for the following year’s kickoff. The government let the NFL use the National Mall, and Tagliabue met with the chairman of the Joint Chiefs in May (two months after the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom) with a plan to make the event a salute to troops. The Pentagon agreed to integrate the concert into Operation Tribute to Freedom, a newly launched initiative to “demonstrate public appreciation for American men and women in uniform.”

“I guess you could cynically look at it and say, well, the NFL is exploiting [the war]. We look at it differently,” Collins told the Washington Post. “We bring people together, and on our most American unofficial holidays like the Super Bowl, we do a pretty good job of wrapping ourselves in the American flag—which I think we have our fans’ permission to do.”

But this was no USO show. The NFL courted corporate sponsors, and PepsiCo paid $2.5 million to promote its newest flavor of soda through the festivities. The Mall was festooned with advertising banners, and Pepsi Vanilla signs covered the fencing that cordoned off a large chunk of the public space during the week leading up to kickoff. Secretary of the Commission of Fine Arts Charles Atherton complained to the Atlanta Constitution that tourists couldn’t “walk down the middle of the Mall between the Capitol and the Washington Monument because of the stage, fencing, Jumbotrons, giant tents and signs.”

The NFL argued that sponsors were needed to pay for a free concert, and a league spokesperson told reporters that a “balance had been struck between commerce and the common good.” That common good was a show headlined by Pepsi spokeswoman Britney Spears. “What the NFL is doing is exactly what Operation Tribute to Freedom is all about,” said Army Col. Dan Wolfe, the initiative’s executive officer.

The concert was free, but fans still needed to get paper tickets to gain access to the Mall. The front section was reserved for 25,000 service members and their families, and a total of 300,000 fans were expected to attend. Besides Spears, the show also included performances by Mary J. Blige, Aerosmith, Good Charlotte, and Aretha Franklin. After the show, giant screens on the Mall broadcast the season opener between Washington and the New York Jets.

Spears, Blige, Franklin, and Good Charlotte frontman Joel Madden appeared at a pre-show press conference alongside uniformed service members to promote the event. When a reporter asked Madden what the concert would mean for his career, he replied, “Uh, free Pepsi and Skins tickets.” The line was met with raucous laughter and applause.

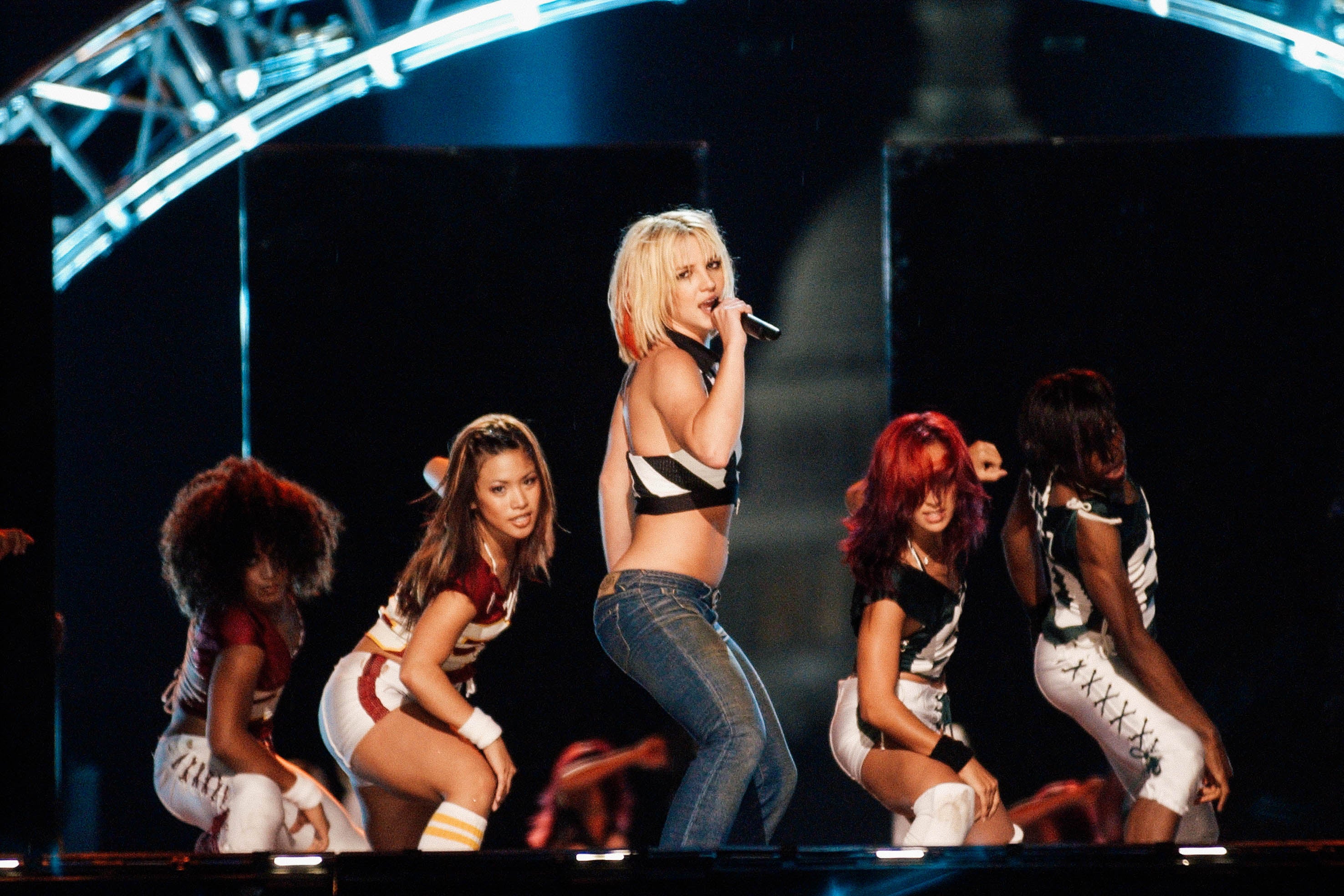

You can find videos of Spears’ performance online. Backup dancers wearing Santana Moss and Jessie Armstead jerseys help her strip down to a referee-striped crop top and hot pants, and during her performance of “I’m a Slave 4 U,” she struggles to remove the microphone from its stand and stops making an effort to lip-sync. Besides the U.S. Capitol looming behind the Pepsi-branded stage, it was a pretty standard Britney Spears concert, but the appearance nonetheless offended some spectators. “Abe Lincoln’s view down the National Mall should not include pop singer Britney Spears gyrating at a Pepsi-sponsored concert,” harangued the lead sentence of an Associated Press report.

Two weeks after the concert, Democratic New Mexico Sen. Jeff Bingaman condemned the “NFL fiasco on the Mall” and introduced an amendment to an appropriations bill that “bars the use of Federal funds to permit the use of the National Mall for a special event unless the permit expressly prohibits the erection, placement, or use of structures and signs bearing commercial advertising.” It passed in a 92-to-4 vote.

Luckily for the NFL, advertising is allowed in Grant Park. But if the league ever wants to kick off its season from the National Mall again, it’ll have to do so without any branding for itself or its generous participating sponsors. What kind of Tribute to Freedom would that be?