Empathy isn’t one of football’s commanding virtues. You don’t play because you care about the other guy’s pain. You play because you want to crush him. Same goes for watching—either you disconnect from the consequences, or you can’t really enjoy it.

While Andrew Luck’s decision to retire has baffled many fans (and I include journalists here, because journalists are the biggest fans), every NFL player understands why he’s doing it. When you make it to the NFL, people tell you that you’re living the dream. They tell you how lucky you are. They tell you it’s a good thing you don’t have to get a real job like they had to, because their lives suck and yours is awesome. When people constantly tell you how great you have it, it’s hard to do anything but nod and agree, even when you feel something else entirely.

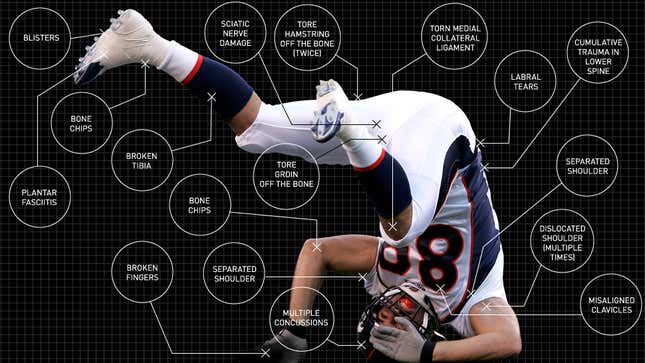

Fans only see NFL players on Sundays, and only the guys who are healthy enough to play. But there are 349 other days of the year, and there only 22 guys on the field at a time. The rest of the days and the rest of the men are caught up in what Andrew Luck referred to as, “the cycle of injury, pain and rehab.” If you play football past high school, you are familiar with it. Three of my six seasons in the NFL ended on injured reserve. Broken tibia, ruptured groin, dislocated/separated shoulders, torn hamstrings, cracked ribs, fingers, concussions, bulging discs, torn knee ligaments, etc. The glory was fleeting; the injuries were constant. And everyone I spoke to reminded me that I was living the dream.

But it was never my dream to be lying on a training table for four hours a day, hooked up to machines, ice bags strapped to my body, while my teammates went to meetings and practiced. It was never my dream to wake up in the morning and wonder how I’d get through the day, to drive to work in pain and confusion, on the verge of tears, trying to understand how things got to this point. What I had done wrong—because, if I was so unhappy while living the dream, I must have done something wrong, right?

It was never my dream to turn on the TV and hear entitled assholes speculating about my health, my injuries, and devoting segments on their shows to discussing my medical file, guffawing their way through segment after segment about the hell I have endured. But that’s what life becomes for NFL players: reciting tired sound bites through gritted teeth and long, sleepless nights, handfuls of pills, and early-morning rehab sessions, sideways looks from coaches who want you on that field, who need you on that field, or else your ass is gone. That feeling that follows you wherever you go, whoever you talk to, that the line of questioning will be—when are you coming back? How’s the shoulder? We’re counting on you!

“Oh, it’s coming along,” you’ll say, knowing that it isn’t. Knowing that it’s only getting worse. Knowing that there is something else in the way, some worm in your conscience preventing the unabashed, enthusiastic healing process that is integral to a speedy football recovery. When the mindset is singular and the body is newer, healing is less complicated. But when the injuries pile on top of one another, and the residue from each one sticks to your bones, and your muscles refuse to forget what you’ve put them through, then your “love of the game” finally gets a cup-check, and that’s right about at the age of 27 or 28.

Call it a confluence of perspectives. The body is no longer cooperating. The adrenaline of game-day has subsided. The adulation of the fans no longer excites. Neither does the big check every week. The shine begins to wear off the Shield. You imagine yourself on a beach. On an island. Far from a football field, free from the mental anguish and paranoia you live with every day. Still, you soldier on, because everything in your life has steered you onto that field.

As a child, the spinning football called me to chase it. My heroes wore red and gold. They postered my walls. By the time I saw John Taylor catch the winning touchdown from Joe Montana in Super Bowl XXIII, I was a full-fledged, capital-B Believer. Whatever I could do to get there, I would. And I did. And once I put on my pads, like all football players, I became a prisoner of my success; a slave to my toughness. I wore that badge with pride and had no qualms about where it was taking me. But then my body started to fail me; injury after injury, disappointment after disappointment.

No matter how rough things got, though, I always worked my way back, never wanting an injury to define me. Never wanting weakness to be my final act. That’s the pact you make when you put on that helmet. That’s what grandpa expected, that’s what dad expects, and what all of your coaches and friends and neighbors expect. That kid who told you you’d never make it. That coach who cut you in college. The reporter who said you weren’t worth a shit. You’ll show them all. You’ll have the last laugh.

And so you play until they drag your lifeless body from the grass, and it’s all you can do to muster a thumbs-up as they wheel you into the tunnel, knowing that’s how you secure your legacy. Every football player knows how to make that sacrifice. But few know how to walk away. That seems to be changing, and thank god for that.

Somewhere, Andrew Luck is laughing.

Nate Jackson played six years in the NFL and has written two books, Slow Getting Up and Fantasy Man. He co-founded Athletes for CARE, a non-profit that advocates for the health and wellness of athletes. He lives in L.A.