As a full-time professional musician and teacher of brass instruments for almost 30 years, I have frequently explained to students the inaccuracy of the old adage that “practice makes perfect” (Practice does not always make perfect – it depends on natural talent, researchers find, 21 August). It is obvious that practice in fact makes permanent, not perfect. That is to say, that if you hack away for hours every day on a musical instrument playing complete nonsense, you will indeed eventually become extremely proficient – at playing complete nonsense.

This is a factor that may have been overlooked in the study that the article references – just how to measure the quality of practice rather than just the quantity. Digging a little deeper into the study shows that the practice quality was only assessed by each individual performer in a self-completed questionnaire, rather than being assessed by a qualified independent source.

The virtuoso trombonist Christian Lindberg practises 10 times a day for 24 minutes at a time. When I asked him why he didn’t round it up to 25 or even 30, he explained that he can’t operate at peak levels for more than 24 minutes at a time, so the practice after that would be redundant or even harmful. This is something that I constantly have to explain to the enthusiastic parents of my pupils that are eager to know how long their child should practise. If concentration is high and clear goals are set, some impressive results can be achieve relatively quickly. But if you practise for hours a day, gazing out of the window with your mind elsewhere, you are going to be disappointed.

Another adage that does the rounds on the music circuit is that amateur musicians practise until they get it right, while professionals practise until they can’t get it wrong. I’m certain that there is some value in this too, and that the 10,000-hour rule does hold some value, but only if the quality of the time spent is top-notch.

Steve Thompson

Head of brass, Eltham College and St Dunstan’s College, London, and trombonist, Shakespeare’s Globe

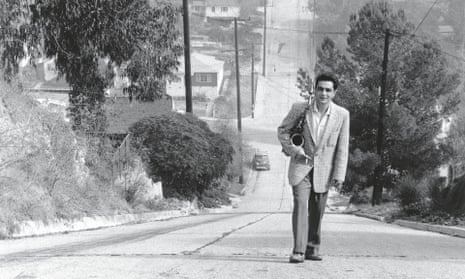

The alto saxophonist Art Pepper never practised, and on one occasion, after six months of not playing, strung out on heroin, his sax in hock, he was persuaded by a group of concerned musicians – Miles Davis’s rhythm section, sans Davis – to make an album with them; they paid to get his horn out of hock and got him into the studio. Pepper, having first wiped the green mould off the horn’s reed, ran through the keys to check they were working and then went straight on to make one of the great jazz albums, Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section – with no alternate takes.

Russ Denton

London

Join the debate – email guardian.letters@theguardian.com

Read more Guardian letters – click here to visit gu.com/letters