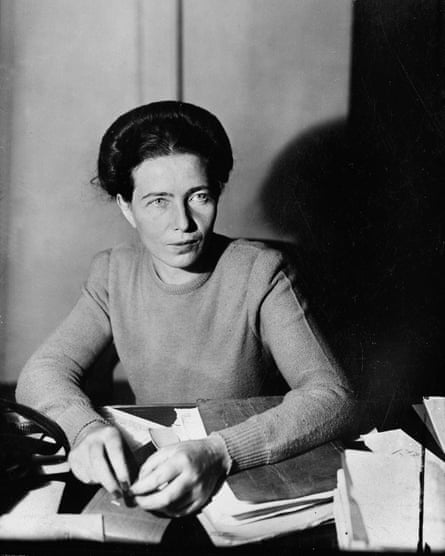

Simone de Beauvoir is a feminist icon. She didn’t just write the feminist book, she wrote the movement’s bible, The Second Sex. She was an engaged intellectual who combined philosophical and literary productivity with real-world political action that led to lasting legislative change. Her life has inspired generations of women seeking independence, and this was largely attributed to her unconventional relationship with the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, which seemed like a love that didn’t come at the cost of her freedom or professional success.

But in the decades since Beauvoir’s death in 1986, several waves of previously unknown letters, diaries and manuscripts have shocked readers who thought they knew her. Her letters to her American lover, Nelson Algren, showed the depth of her passion for another man. Letters to Sartre revealed not only that she had lesbian relationships, but that her lovers were young and her students. There is no doubt now that she hid both significant professional successes and serious moral failings from the story she told in her autobiographies. So what are we to make of the author of The Second Sex, 70 years on from its publication? In light of what she didn’t tell us, was she as feminist as we thought?

The short answer? It depends on what it means to be feminist and which Beauvoir you have in mind. (The long answer took a book to write.) But it is now clear that Beauvoir’s most questionable moments played an important role in transforming her convictions; that she condemned her own actions and renounced the philosophy that underpinned some of her and Sartre’s most infamous behaviour; and that she became several different kinds of feminist over the course of her career. There are chapters of Beauvoir’s life that read less like liberated sex and more like case studies in sexism – but there are also instances where she decided to call it out, even when that meant accusing herself. Her life raises a question she had to live: are we the sum of all of our actions, or the sum of our worst?

Evaluating the feminism or “worst actions” of a 20th-century philosopher whose life has been highly politicised is no easy task. In the 20th and 21st centuries, a wide variety of feminisms have emerged, often contradicting each other and frequently invoking strong progress narratives to show how previous generations’ (or even contemporary opponents’) efforts were wanting. The contents of these progress narratives vary widely depending on the political and historical context: for example, the UK celebrated its centenary of women’s suffrage (for women married and over 30, admittedly) in 2018, but French women only gained the right to vote two-and-a-half decades later, in 1944. So it was surprising to discover, when researching the reception of The Second Sex in France in 1949, to find it – and feminism in general – vociferously dismissed as passé.

Gradually surprise gave way to suspicion, as a pattern emerged in reviews: again and again, Beauvoir was criticised for thinking “feminism was still relevant”, for writing female protagonists in her novels, and spending too many pages on women’s points of view. “What about men?” reviewers asked. What they liked best was the Beauvoir who told them what it was like to be with Sartre, the woman who fuelled imaginary fires with fictions of free love.

Although philosophers and scholars of French literature have recognised Beauvoir’s intellectual importance and independence for decades, representations of her life have often focused disproportionately on her early adulthood, when she formed her legendary romantic “pact” with Sartre. One day in 1929, near the Carrousel du Louvre, they decided theirs would be an open relationship, forsaking no others: they were “essential” to one another, they said, but would keep “contingent” lovers on the side. In 1929, this was a curious arrangement – and it has continued to intrigue readers.

Less attention has been given to the content of Beauvoir’s own philosophy, before and after she met Sartre. It is this dimension of the newly released diaries and letters that makes it especially interesting to reconsider her life and legacy. Tarnished or not, she was a woman who claimed that women’s lives should not be reduced to erotic plots – and her life has persistently been reduced to an erotic plot. And what she said about feminism repeatedly made people angry – so if she was passé, what was there to be angry about?

Behind the mythical persona was a philosopher who wanted women to be “free to choose themselves”. Human beings were “the sum of their actions”, and she believed it would be reassuring to think that we each have a foreordained destiny, a unique raison d’etre that justifies our existence. But it would also be false. For Beauvoir, each human being is a becoming without a blueprint. She started developing this view in the late 1920s, before she met Sartre, and began to publish her philosophical disagreements with him in the 1940s – but by then they were both become famous in France and her ideas were often credited to him. (And outside France, important texts by Beauvoir were untranslated.)

Beauvoir developed her ethics after rejecting the perspective that underpinned her relationships with women in the 1930s and early 1940s. These ethics would also lay the philosophical foundations for The Second Sex. Here, she claimed that the desire to feel that one’s existence is “justified” affects women differently than men, because women are expected to justify their existence by loving others. She argued that becoming a woman was difficult in distinctive ways, because history, literature, psychoanalysis and biology presented women with incompatible myths of femininity instead of encouraging them to become free, fallible and fully human.

In 1949, her critics described her as anti-women, anti-maternal, anti-marriage. But although she thought economic work helped women, she did not think that work by itself could make women free, nor that marriage and motherhood were without value. The goal of The Second Sex was to help women cultivate a confidence in their own vision of the world – to recognise the value of their own freedom – that she later called rapport à soi (self-rapport). Because women couldn’t live up to all the incompatible myths of femininity, Beauvoir thought, they often felt like failures. Instead of asking themselves what they wanted for their lives, they berated themselves for not being what others wanted.

Beauvoir’s novels were often criticised for having female characters who did not live up to her feminist ideals. But after cataloguing stifling stereotypes of femininity, Beauvoir did not want to furnish new galleries with oppressive mythical portraits. She did not want to write “strong women” who reinforced women’s feelings of division and inadequacy. In a period when possibilities for women’s lives were differently constrained than they are today, she wanted her reader to be able to dream, fail and dream again, always in the knowledge that failing didn’t make them a failure.

Whatever else it was, Beauvoir’s feminism was not triumphalist and her literary strategy was risky when she turned to writing her own story. Over the four volumes of her autobiography she hid times when she failed to live up to her own standards – and she hid some when she exceeded even her own dreams for herself. She never set out to be the woman who wrote the feminist bible, and the life she lived before she did contained several things she wished could be otherwise. But the catch about becoming is that you can’t undo the past; you can only renegotiate its meaning as you look to the future.

When Beauvoir wrote about her life she acknowledged that there were some “unavoidable discretions” that prevented her from telling all. She made no secret of the fact that her life was distorted by her omissions – but that is one of the reasons why it is so interesting to read it again in light of them. The word distortion comes from the Latin torquere – to twist, to torture. As a person, Beauvoir had to live with her distorted public persona for decades, and sometimes its consequences were twisted and torturous. But whether or not you like your feminism triumphalist or your autobiographies transparent, Beauvoir’s chapter in the history of feminism is one to interrogate, not ignore – because of what she did and what she thought, and also because of the way what she did has been too often used to distract people from what she thought.