In the Straits: An Inmate Turned Millionaire Turned Lone Survivor

Illustration by Owen Freeman

The waves roll in like ghosts. They’re invisible, gliding fast toward the boat, before they emerge from the dark to reveal themselves in the beam of light that pours down from the vessel. Three and sometimes four feet tall, the waves slap the bow, propelling the boat skyward until it thuds back down and the next white-crested apparition hits.

“Think we ought to turn back?” asks the man gripping the steering wheel.

“We’ve just got to push through,” answers his friend. “You don’t want to try to turn around in this shit anyway, because it’ll swamp you.” They should keep the bow pointed straight at the incoming waves, the friend says; if one hits them sideways they’ll capsize.

Just minutes ago, as the two men left the marina at Cornet Bay, the forecast they consulted called for small, two-foot waves. Now in the middle of Deception Pass in near-complete darkness at 4:30am it’s clear that forecast was wrong. And so Michael Powers, 40, holds the wheel steady. Richard Seay, 54, offers guidance. Familiar roles for them both.

When they met a decade and a half earlier Powers was just a few years out of prison. Seay (pronounced like “sea”) was a drywall installation veteran, cantankerous and headstrong. Together they built a construction company—Powers in charge, Seay grumbling into his ear—a company that these days hauls in some $20 million a year. The two were inseparable. Powers even married Seay’s cousin, Heidi. Lately though, things between the guys had turned awkward. Citing a poor attitude, Powers had fired Seay—twice. They avoided talking business at family gatherings. Only recently had they called a truce. Today was going to be special. An unforgettable Thursday: May 2, 2019, the first day of halibut season.

Richard Seay (left) and Michael Powers.

They convened that morning at Powers’s office in Arlington, 40 miles north of Seattle, and drove up together in his Ford F-150, pulling the boat, a 20-foot Duckworth Navigator Sport. The pair reached Cornet Bay on Whidbey Island around 4am. After backing the craft into the water they set a course for the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The route took them under the Deception Pass Bridge and through the smaller strait of the Pass itself.

In the depths below swim creatures as big as pit bulls. Pacific halibut, the world’s largest flatfish—their eyes on one side of their head to scan for prey—possess astonishing strength. Taken alive the beasts can thrash apart a boat’s interior. Some sportsmen even pack firearms to put halibut out of their misery before bringing them aboard. Powers has stashed a small handgun in the front pocket of his jeans for that reason.

As the waves hammer the boat, he does as Seay advises. Pushes through. Once they’re out of the Pass and into more open water the waves will calm and they can start fishing, they’re both sure.

They don’t know that less than an hour after setting the boat in the bay, only one of them will be alive.

Deception Pass, the narrow strait where the disaster unfolds, is the centerpiece of the Pacific Northwest’s most mesmerizing vista. Cars regularly come to a standstill along the two cantilever bridges that connect Whidbey Island and Fidalgo Island—collectively known as Deception Pass Bridge—as passengers steal a few extra seconds of the view, sometimes backing up traffic for long stretches.

In the light of day the water blazes an intense blue, rocky cliffs and lush evergreens jutting up on both sides. Looking west from the slender, two-lane bridge you can easily make out Deception Island a little over a mile away at the far end of the strait—an emerald gem in an azure pool. To the left of the strait, a thin vein of beach traces Whidbey Island’s northernmost reach with sun-bleached driftwood and millions of smooth, sea-worn stones.

The lavish canvas hides a truth about Deception Pass. You don’t have to peel too far back in time to see that, under the wrong conditions, this is a perilous place to stick a boat. News archives teem with reports of sunken craft, drownings, bodies never found.

So treacherous are the waters that speed through the Pass, kayakers come to train and test their paddling mettle against currents that are among the world’s most powerful, as swift as eight knots (or nine miles per hour). But the danger can be invisible to the naked eye. During the day the rock- and driftwood-strewn shore is crowded with beachcombers and tourists agog at the panorama. On the bridge pedestrians soak in the view from 180 feet up.

Not at 4:45am. At that time there are no spectators. No one to witness a 20-foot sport fishing boat in trouble. No one to come to the aid of two men drowning.

The wave that overcomes Michael Powers’s Duckworth is unlike anything they’ve seen all morning. Even in the sparse light beaming down from the boat and illuminating about 10 feet in front of them Powers and Seay can see this one is different. It’s not a wave so much as a wall. A vertical barricade of water, maybe as tall as 12 feet.

In the seconds before it hits, Powers thinks: tsunami. Could there have been an earthquake? Did the earth move and send this rolling destroyer? But it’s the words that issue from Seay’s mouth that scare Powers the most. Seay, who’s been the reassuring voice since they left the dock, has time to get out two chilling syllables.

“Oh. No.”

The boat doesn’t rise with this wave like it did the others. There’s no incline for the vessel to glide up. Instead the bow stabs into the wall. The wave blasts the windshield, smashing all three window panels instantly. The sound reminds Powers of a car crash. Shattering glass. The violent beating against metal.

The wave passes, drenching the men, both still in their high-backed seats. As soon as the wave is behind them they notice: The boat lists to its port side, at about 30 degrees.

Powers thinks the craft will right itself. He fumbles in the dark and turns on the bilge pumps to empty out the water; he stands on the starboard side, hoping his weight will level things out.

Then the boat crackles with static. Powers sees the radio’s orange light illuminate. It’s Seay, mic in hand, pleading.

“Mayday. Mayday. We’re in trouble. We need help.”

Powers fumbles again in the dark. He lifts a seat cushion and pulls out two life preservers. He hands one to Seay just before another big wave hits.

One second Powers stands in the boat, the next he’s out—and completely under water.

His first thought: I didn’t take a big breath before I went under. He’s still caught in the wave, can feel it push him down. His impulse is to start kicking to reach the surface for at least one gulp of air. Then he realizes he doesn’t know which way is up. He waits. The life jacket, still clutched in his hand, pulls him as he fixates on his empty lungs. I don’t have a breath. I don’t have a breath. I don’t have a breath. His head breaks the surface.

He sees the boat. It’s completely vertical, straight up and down like in the movie Titanic. The front sticks out maybe three feet above the water and descends quickly.

Blurp. It’s gone.

He starts yelling for Seay. “Rich!” He hears moaning and swims in what he thinks is the right direction, six-foot waves throwing him about. As his eyes adjust to the dark he spots his friend, floating on his back, 50 feet away.

He first laid eyes on Richard Seay at a jobsite installing drywall. Truth is, he thought he was a total ass. Seay, 14 years older than Powers—then about 26—seemed to look down on the kid. “I don’t use routers,” the balding, middle-age man boasted. Who is this guy, Powers wondered, other than a jerk?

When Powers launched his own drywall operation, not easy for someone like him, who had been to prison twice, a friend recommended hiring Seay. “Rich? The guy I did the side job with?” Powers was incredulous. “I don’t like that guy.”

But the friend pressed him to give Seay a chance. “He’s really a good hand. He’s been doing it a long time.”

It was one of the best decisions Powers ever made. “He turned out to be completely invaluable,” he would recall years later. Seay ran all the big jobs in the field. Powers ran the office and landed the big contracts.

They cavorted outside of work, too. Fishing, gambling, drinking. Powers had grown up without a dad, but it would be a stretch to call Seay a father figure. He was more like Shakespeare’s character Falstaff, the insatiable and carousing but ultimately big hearted advisor to Prince Hal, the future King Henry the Fifth. That is if Prince Hal were a two-time ex-con with an amputated index finger and a taste for hip-hop.

In casinos Seay would get the pair kicked out before they even had a drop to drink. At the blackjack table one night at Angel of the Winds casino, joking around with each other, they laughed so hard that Seay, stone-cold sober, fell out of his chair. When they tried to order, the server informed them they were cut off. “But,” Seay complained, “this is our first stop tonight.”

When Powers invited friends to watch mixed martial arts on pay-per-view at his new house in rural Arlington, Seay brought his cousin, Heidi, and her dad. Out back, standing around the bonfire that night, Powers fell for Heidi hard. She was a single mom three years his senior. He was a single parent by then, too. That night he told her father he was going to marry her.

When Heidi and Powers formed their own family—her daughter, his daughter, his and her son—Seay stayed very much a part of it. He lived behind a park and the kids would come over and play. He made their son a kite and bought him remote control toys.

A photo of Powers and Seay seated at a sushi restaurant a few years back illustrates their dynamic perfectly. Powers, his face scruffy, wears a Seahawks T-shirt and beanie. Seay, with a horseshoe of graying hair wrapped around the back of his skull, sports a maroon T-shirt. Together they hold up for the camera a massive platter weighed down by three python-thick sushi rolls. The look on Powers’s face is your standard issue “I’m about to enjoy some great fucking sushi” smile. Seay emotes something else. He’s got his arm around Powers, and his expression is one you’d expect from a character in a movie who’s about to lay some truth on you. His eyes squint. His lips purse. The mouth is open but just off to the side in a kind of stage whisper, the better to tell his audience of one the secrets of life.

When he reaches his friend in the water Powers sees that Seay had managed to slip the red life preserver over his neck but didn’t get the straps around his torso. He’s floating on his back. His eyes are closed and he moans. A grunt escapes with each breath.

Powers yells. “Rich! Rich! Talk to me.” Again and again the waves splash over the tops of their heads. Whenever Powers sees one get close he shuts his mouth to keep the water out. But Seay, unconscious, keeps his mouth open.

Powers shouts again. “You’ve got to open your eyes. Talk to me.” He tries to slap Seay awake, like in the movies. Nothing works.

With a life jacket still in one hand, Powers pulls Seay up by the jeans, bringing him closer, and places his friend’s head up on his shoulder, so it’s at least a couple of inches higher out of the water.

He holds him like that as he listens for the helicopter blades, hoping that Seay’s radio Mayday got out, that help is coming. He also scans for a boat he remembers motoring behind them on their right flank, shortly before the biggest wave hit. But he doesn’t see its lights. Maybe it got hit by the same wave, its passengers now in the water, too. He screams, hoping he can locate the other passengers. Nothing.

He finally pulls on the life jacket clutched in his hand, only to realize it’s too small to be completely effective. In the rush he’d actually grabbed from under the boat seat his 11-year-old daughter’s yellow junior-size vest.

Twenty minutes in, he hears a gargle.

The moaning stops and it sounds to Powers like Seay is choking on water. He spins him around so they’re face to face. He attempts resuscitation, plugging his nose and blowing a breath into his mouth. Foam comes out. Powers washes the foam away with water and blows in another breath. He puts a hand on Seay’s back and with the other tries a chest compression, but he can’t get enough leverage to make a difference.

He performs mouth-to-mouth and the compressions for another 10 minutes until there there’s no more foam coming out. There’s no more gargling either. No breath. Richard Seay is gone.

When sunrise comes at 5:45 Powers has spent an hour in water that’s later estimated to be 47 degrees. (Experts say a human can remain in the water at that temperature for 30 to 60 minutes before going unconscious—and one to three hours before death.) As the sky slowly brightens and the water calms, he takes in his surroundings.

He can make out the Deception Pass Bridge, less than a mile away. To the south, the driftwood-covered beach of Whidbey Island. In the other direction, and much closer, a grassy hilltop that seems to rise straight out of the water, an appendage of Fidalgo Island.

But it’s what he doesn’t see that holds Powers’s attention. There are no boats. Not one. How can that be? It’s the opening day of halibut season. These waters are usually lousy with people fishing on opening day. Where the hell are all the boats?

Still holding Seay’s lifeless body he takes another look at that grassy outcropping. An idea blooms in his mind. A sudden sense of purpose.

Powers lost his best friend—his cousin by marriage—on the morning of May 2, 2019, the first day of halibut season.

Image: Kyle Johnson

Alone was nothing new. As a kid, so many things made him feel alone, apart. Those stupid green trinkets at Wellington Elementary didn’t help. In the mid-1980s they went to the low-income students, who exchanged the plastic octagon vouchers for lunch in the cafeteria. A young Mike Powers, then six, didn’t like the way the tokens made him feel. They embarrassed him. Signaled to the other kids that he was poor. Not that he wasn’t. His mom was raising two children on a telemarketer’s salary.

Another thing that set him apart: adoption. Bill and Elizabeth Powers had a biological daughter, nine-year-old Niko, but when a second child was stillborn they decided to adopt. In 1978 they brought home a son, born to a 14-year-old mother in Spokane. Bill and Elizabeth named the infant Michael William Powers (the middle name after Bill).

The promise of a prosperous, two-parent household dissolved just three and a half years later. On December 5, 1981, at age 39, Bill Powers, a circulation manager at the Journal American (today’s Bellevue Reporter), died of a heart attack. Without Bill, or his salary, Elizabeth struggled to support the family. She, Niko, and Mike bounced from home to home—in and around Woodinville and Redmond. Every six or nine months a new place.

Those green octagon tokens were just the start. Elizabeth’s adopted son never felt like he belonged. His clothes weren’t quite right. He was overweight. He wore glasses. Picture a corpulent, bespectacled kid in a mullet and a pink DARE shirt and you have a good idea of how Michael Powers looked in the 1980s.

To cope, he acted out. When the family rented an apartment next to an Albertsons, Mike acquired the habit of slipping into the grocery store before he caught the bus to school. He’d swipe Twinkies and other snacks. At a toy store he stole Legos. His desire to fit in led to more crimes. When he was a teenager and got a job at Safeway he pinched cartons of cigarettes. He sold the pilfered smokes to the kids who hung out at the Redmond YMCA, then made friends with his clientele.

He left home at 15, squatting with other teens in an abandoned building in the University District. One kid taught him how to pry the locks of UW dorm rooms with a credit card. He stole computers and bikes, turned them around for cash.

At 18 he found a job as a telemarketer like his mom and moved into his own place in an apartment complex a few short blocks from Crossroads mall in Bellevue. He turned his unit into a party pad. Music posters. Black lights. He cleared out a closet and let a friend crash there. By now he’d updated his look: pierced ears—in which he stuck a gold hoop earring, a clear stud, or both—and a gold chain around his neck.

The life of the party was methamphetamine, which he used heavily, including intravenously. Meth became the answer to everything. The answer to being more social. To maintaining a semblance of confidence. It even became a source of income.

On Friday morning, October 25, 1996, the Eastside Narcotics Task Force rushed the second floor of the apartment complex, warrant in hand, and busted open door No. 2708. As that happened, officers standing behind the unit saw two bags of methamphetamine tossed out a window, in an apparent effort to destroy evidence. Inside the cops found Mike and four friends, one of whom had thrown the drugs out the window to protect Mike. On the coffee table sat a scale—for portioning out meth—and, by the TV, an unloaded sawed-off shotgun.

Convicted of two felony counts of possession and intent to distribute a controlled substance, Mike, still just 18, received a 41-month prison sentence.

When he was released, at age 20, a friend introduced him to the construction trade, where a journeyman might pull in $27 an hour installing drywall. Big money to Mike, who had moved back in with his mom. He entered an apprenticeship program and took a drywall job.

That same friend also introduced him to heroin. The drug consumed Mike. Within six months he was regularly dope sick, experiencing severe withdrawal if he didn’t have heroin—vomiting, running nose, uncontrollable rocking back and forth.

Part of him even missed prison. In prison he worked out and stayed in shape and made lots of friends. In prison they make your meals for you. They do the dishes. It’s not hard, and life outside had gotten really hard.

He eventually lost his job after showing up one day strung out and leaving early. He’d been in the construction site’s porta-potty, shooting up.

Elizabeth entered his bedroom one afternoon and found him passed out, with the needle still sticking out of his arm, his lips blue. She tried to slap him awake, called 911. Paramedics injected him with Narcan, the opioid blocker.

He had likely just escaped death, but he turned his ire toward Elizabeth. “Mom, what did you do? You can’t call 911. My PO”—meaning his probation officer—“is going to find out about this.”

“You weren’t breathing,” she fired back.

To quit he tried detox. A doctor prescribed a cocktail of seven powerful detox drugs. Mike took them at home. He lasted three days.

On Labor Day morning, September 6, 1999, Mike decided he couldn’t take it any longer. He’d rather be back on heroin, in prison, or dead. He hatched a plan to bus to Seattle, a 20-mile ride away, and rob somebody of their drugs. He left the house with a pocket knife.

On the bus and flattened by withdrawal, the only way he could make the nausea stop was lay in the seat in the fetal position and rock back and forth. He stayed that way, rocking, on what seemed like the longest mass transit ride in the world, until he sat up in time to notice a bustling commercial area. He exited at the next stop, but he was in Redmond, not Seattle—another 15 miles farther—which he didn’t realize until the bus pulled away.

Still intent on Seattle, he stepped into a QFC to buy needles. He would need them when he got the drugs anyway. The pharmacist took one look at him and turned him away.

Outside he noticed a line of cars queued in front of a drive-through ATM. Around 1:25pm, according to King County Superior Court records, Mike approached a Chevy truck near the ATM. He tried to open the passenger-side door. It was locked. So he brandished the knife, demanding the man sitting behind the wheel unlock the door. When the man refused and began to drive away, Mike tried to break the passenger-side window, slamming it hard with his elbow. The truck screeched away, turning heads.

Panicked, Mike ran back to the QFC parking lot, and spotted a woman getting into the passenger seat of a Jeep Cherokee. Still brandishing the knife he pushed her out of the way and jumped in. He looked for the keys and then noticed: a three-year-old child in the back seat. He jumped back out.

He tried to calm her. “Lady, I’m not going to hurt you. I promise. I promise.” He said he just needed a ride to Seattle. She played along just enough to hit the panic button on her key fob.

The alarm blared throughout the parking lot, drawing attention. Mike ran again, but didn’t get far before two cop cars sped his way.

Apprehended and sitting on a curb, his elbow broken from trying to bust the truck window, he wished he could tell the cops standing in front of him the truth, to let the words escape and proclaim the only thing he really needed and even wanted in that moment: “Just take me to jail. Just put me in a cell.”

The sun is little more than a white ball perceivable through the gray screed of clouds above Deception Pass, but as the morning matures and the sky pales Powers gains a better sense of his situation. Gauging the distance between himself and the nearest solid ground—the cliff capped by the grassy meadow—he’s convinced a good, hard swim will get him there.

First he has a big decision to make. When he tries to swim with Seay’s body, dragging him by his red flannel shirt, he gets almost nowhere. Without the body to pull he might have a decent chance. And with Seay’s life preserver on himself an even better one. But it’s Rich. His best friend of 15 years. His cousin by marriage. If he takes the life preserver the body will sink and likely won’t be recovered. He imagines the funeral. Rich’s mom—the sister of Powers’s mother-in-law—and girlfriend won’t get to see him, not even his body, one last time.

For 10 or 15 minutes he struggles with the inner battle, in dialogue with himself. Then suddenly that dialogue is with Seay. If Rich could talk, what would he suggest? What would Rich say to do? He decides his friend and trusted adviser would tell him to do everything he can to save himself. Anything you can do to increase chances of survival—do it.

Even while Powers removes the life preserver from Seay’s body he’s conflicted. It’s a selfish decision, he thinks. A hero wouldn’t do this. But a hero would. In a sense, one of his just told him to do it.

Michael Powers starts swimming north, toward the grass-covered outcropping.

The final stint in prison is enough. After his arrest for the attempted robberies in the Redmond parking lot—and one last run-in with the law, a crashed Chevy Malibu while high at the wheel—the state sent Michael Powers to the maximum security prison in Walla Walla, and later to minimum security in Yacolt.

Released September 4, 2002, he knew he never wanted to return. Two months in a Seattle homeless shelter convinced him he never wanted the drug or street life again either.

He started where he left off, a drywall installation apprenticeship. One of the first jobs was a new Pottery Barn in University Village. He’d worked out in prison and to stay in shape he started going to the gym before work and discovered he had more energy than the other guys on the jobsite, who seemed kept alive only by the grace of their coffee thermoses.

He also found he was a really good drywall framer. “I’m taking you on every job,” the foreman told him. Work became his new addiction. Wake up. Go to work. Go to a side job. Go home. Repeat. Except this drug brought in money instead of sending it up a vein in his arm.

Amazingly he qualified for a subprime home loan—the type that would crash the market just five years later—on a spread in Arlington, an hour drive from the jobsites in Seattle. Eleven months after his prison release he closed on the house. The mortgage ate up his paychecks fast. He didn’t have money left over for reliable transportation, but found a deal on an old Ford Ranger. He convinced the owner to let him pay the $1,500 in installments. But that meant almost nothing left from payday for his other financial obligations, including the house payment.

At work he heard about a contest for apprentices at the Evergreen State Fair. The prize: exactly $1,500 in cash, plus the bragging rights as the best new drywaller in the state.

He won, and with that win Michael Powers became one of the most sought-after construction workers in the region. Well-placed mentors in the industry took him out for lunch, asking what he wanted to do next. The future, so unlike his past, looked promising.

But how could it be that easy? Of course it couldn’t.

About three months later at a side job the Skilsaw bucked backwards. It chewed through his left hand and took his index finger clean off. Surgeons at Harborview were unable to sew it back on. Without his index finger or full use of his damaged hand his construction career appeared over. The best drywall hanging apprentice in Washington state…couldn’t hang drywall.

He spun into a deep depression. Gained 50 pounds. Out of money, he frequented a food bank. Finally, after three months, he landed an interview for a job working in the office of a construction company. “I’ll get you doughnuts and make coffee and clean your office,” he told John, the owner.

“I’ve got this software that I bought and spent a bunch of money on,” John said, “but I’ve never really figured out how to use it…. Why don’t you figure it out?” Powers took to it fast. The software was for creating construction bids. He spent weeks building databases and was soon bidding for new business.

The company pulled in $3 million one year, $4 million the next. John offered Mike $70,000 a year to run his office—more money than the telemarketer’s son had ever seen.

He soon branched out on his own, forming his own company in 2007. He brought on Rich and that was that. The company, Powerco, now Alliance Partitions Systems, installs drywall for commercial and government clients. Projects include new buildings for the likes of Fred Meyer, Zara, King County Library System, the Seattle Fire Department, and the Kirkland Police Department. The ups and downs tracked with the Seattle building boom and building bust, bringing in $2.5 million in 2008, but $1.6 million in 2010 due to the recession.

Along the way his leadership inspired loyalty, just as it had a decade earlier, when a friend tossed meth out of that apartment window to protect him. On a Friday in 2010, in the middle of a project, the Kenmore City Hall, Mike realized he could no longer make payroll. He and Rich Seay drove out to the jobsite to deliver the news. The company, he told the crew, was finished. Through tears Mike said how sorry he was. They’d get one more paycheck, but he and Seay would have to finish the project themselves, just the two of them.

When Mike returned on Monday, he was astonished. The entire crew had shown up. “What are you guys doing here? I let you go on Friday. I told you I don’t have any money left.”

“That’s okay, Mike, you pay us when you can.”

Once out of the recession the company took off again. In the first half of 2019, Alliance Partitions did more than $14 million in jobs, putting it on track for its highest grossing year ever.

Meanwhile, Mike and Heidi, married in October 2010, built a life. They bought a big house in Tulalip, another on the shores of Lake Goodwin. Together they’re raising three kids. The couple even weathered a separation last year. Still legally divorced, they’re back living together in the same home.

In some ways it was like he’d never been to prison. Ex-cons lose their right to vote and to own firearms. Mike successfully petitioned the state, and in 2016 he acquired a conceal-carry permit and voted for the first time in his life.

The morning Mike drove to the office to pick up Seay for their halibut fishing trip, his life could not have been better. The ex-con turned millionaire. Prince Hal in a kingdom of his own making.

Michael Powers, photographed at Deception Pass, served two prison sentences before he founded a thriving construction company.

Image: Kyle Johnson

How could he come so far only to have it end this way? Michael Powers is losing hope. As he swam north toward the grassy outcropping the current pulled him farther away until the beach to the south became the closer option. But as he swam toward the beach the current pushed him again, farther west, out into the much larger Strait of Juan de Fuca. Now he’s drifting south, down the west coast of Whidbey Island.

At some point he realizes his waterproof watch is working and he’s able to track the hours. He’s been in the water for three. No matter how hard he swims the current pulls him away from the shore, and keeps pushing him south.

Four hours in the water. He still has the gun he tucked into his jeans pocket back at Cornet Bay, just another tool in his halibut fishing kit. It’s got four bullets. Around 9am he finally spots a fishing boat and decides he’ll shoot the gun in the air to draw the crew’s attention.

His fingers are so stiff reaching into his pocket is a painful, agonizing struggle. Once the gun’s out he fires until it’s empty. Crack. Crack. Crack. Crack. He drops the pistol and swings his arms back and forth, making a rainbow of swinging limbs, screaming at the top of his lungs. No one on the boat hears him over the noise of the engine or sees him in the undulating water. He is a tiny, imperceptible dot in a literal sea of gray.

Five hours in the water. He keeps trying to swim to shore but it’s feeling like a lost cause. He can barely move his hands now. His fingers are locked, hands like claws trying to gain purchase in the water. He places the red life preserver under his knees and floats on his back.

Six hours in the water. What will happen after he’s gone? He thinks about his business and all the people who rely on him and the work. He loses it at the thought of his kids. He thinks about them one by one. He never had a father. Now they won’t either. Will their early lives spiral the way his did? He imagines the story they’ll tell for the rest of their lives, about how their dad died when they were 8, 11, and 13, respectively. He thinks of the girls in particular, about how they’re coming into their teenage years. He feels like he’s leaving them when they need him most.

Around 11am, he loses consciousness.

Joe Robinson is at the helm of his boat, the Macy Rae, off the west coast of Whidbey Island, when he notices two vessels in the distance behaving strangely. The yacht appears to be ramming the sailboat. He’s been on boats nearly his whole life and he’s never seen anything like this. The halibut—and his three fishing pals on board—will have to wait. The lanky, 43-year-old carpenter and former professional crab fisherman cuts a path to go see what the hell’s going on.

As he closes in with the Macy Rae—a 20-foot aluminum vessel named after his daughter—Robinson determines no one’s ramming anything. The yacht and sailboat are circling each other. And the passengers are out at the railings looking down, throwing a life ring and other objects overboard to something below.

It’s a man in the water, floating on his back.

Robinson yells over. “Is he with you guys? Is he off one of your boats?”

No.

“What the fuck are you guys doing then?”

Robinson moves in; the yacht and sailboat steer out of the way.

The eyes of the man in the water are wide open, but when Robinson and his crew toss him the end of a rescue rope the man does not respond. It bounces off his shoulder and he doesn’t try to grab or reach for it. Doesn’t react at all.

Robinson yells. “Hey! Hey!” He can see his arms moving, treading water. “Does this guy speak English?” Maybe he’s foreign. Maybe he fell off a cargo ship. Robinson angles his boat so it’s alongside the castaway. One of his crew pulls him aboard.

His body temperature is dangerously low. Robinson recognizes the extreme hypothermia. They pull off the tiny yellow life vest, cut away his clothes, wrap him in a blanket, and rub his chest and legs to get his circulation going.

When Robinson radios the Coast Guard they tell him to bring the man to Cornet Bay. A 40-minute boat ride. Robinson is livid. His passenger doesn’t have that much time.

He ends the conversation and calls 911. Tells the dispatcher he’s headed toward the closest shore, at the south end of Joseph Whidbey State Park. Twelve minutes later, with sheriff deputies, EMTs, and an ambulance parked nearby, Joe Robinson risks sacrificing the Macy Rae and runs it aground on the rocky beach.

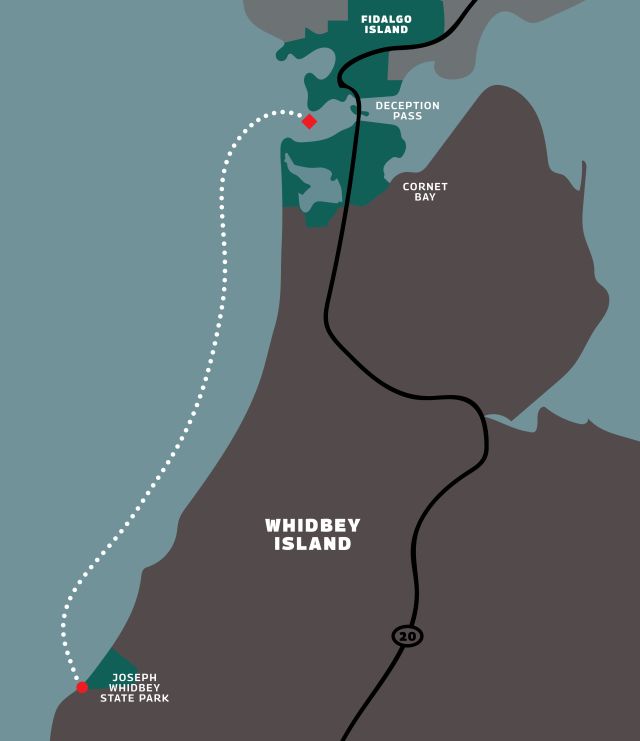

The fishing boat capsized near Deception Pass, versus where Powers, nearly eight hours later, was brought to shore.

Image: Jane Sherman

Michael Powers spent nearly eight hours in the water, from about 4:45am, when his boat went down, until 12:30pm, when Joe Robinson and crew pulled him out. Why did no one come to his rescue before that? Blame a tangled web of interagency communications.

At 4:57am the captain of a boat in Deception Pass—the one Mike remembered being at his right flank—called 911. The captain told the dispatcher that he had been behind a boat (perceptible only by its lights) then suddenly saw it disappear in a wave. Fearing for his own boat’s safety the captain waited to reach calmer waters before making the call. The Island County Sheriff’s Office immediately sent rescue craft in that direction. But the Coast Guard received a report that a vessel with a matching description made it safely ashore; the search was called off.

Nevertheless, the 911 call and the volatile waves in the Pass prompted a brief shutdown of the Cornet Bay boat launch. That’s why Mike, to his dismay, never saw any boats in the Pass, on one of the most popular boating days of the year.

After the rescue by Joe Robinson, a helicopter brought Mike to Harborview Medical Center in Seattle at 2:45pm. When he awoke the last thing he could remember was floating in the water, contemplating his death, some four hours earlier. The medical staff crowding around his bed seemed afraid to tell him something, debating under their breath about how to deliver some news.

Mike, despite the tubes down his throat, croaked, “I’m aware Richard didn’t make it.”

Joe Robinson (left) and the crew that helped rescue Powers (right) at Harborview, May 3, 2019.

Image: Courtesy Mike Powers

Rescuers, he learned, had recovered Seay’s body. Mike would later recall their drive up to Cornet Bay that morning, how they had talked in a way they hadn’t in years. They revisited the two times Mike had fired Seay for hurting morale by complaining, loudly, about new employees. Seay said he enjoyed his new job—constructing Sound Transit’s Northgate station. It was the right place for him, he said, because there, where he wasn’t so personally and psychologically invested, he could focus on what he loved about the work: building something. He thanked his friend for freeing him.

Now that friend struggled to survive. In the hospital Mike couldn’t move his arms or legs and feared he was permanently paralyzed. A nurse pulled Heidi aside in the ICU. He’s here and alive, the nurse said, which is a good sign, but he’s not out of the danger zone. The staff worried about blood clots and brain damage from prolonged exposure to such cold water.

But as the hours crept by, with friends and family dropping in—his mom, Heidi’s mom, Seay’s girlfriend, even Joe Robinson and the crew from the Macy Rae—Powers’s body healed. After two days he was discharged and back into his old life. Make that his new old life.

On a spectacularly bright Friday afternoon in June, Michael Powers wheels his white, chrome-trimmed Ford F-150—special King Ranch edition—out of the parking lot of his shop, Alliance Partition Systems in Arlington. He just bid a good weekend to his staff, including the newest employee, Joe Robinson. (That’s right, Powers hired his rescuer.) The truck turns onto Smokey Point Boulevard and the sun hits that immaculate trim, sending glints of reflected light all around.

Thirteen minutes later he pulls into a tony neighborhood that’s as far from an abandoned U District building as a homeless teenager could hope to travel. He reaches a long driveway and parks in front of the house, a white and brown, 3,400-square-foot manse.

He’s wearing shorts and a gray Seahawks T-shirt with the sleeves cut off, exposing a tattoo of an Irish cross on his right shoulder, on his left a heart with “Heidi” and their kids’ names scrawled through it. He carries a clear plastic bag containing brand new basketball jerseys into the house. He had them made for his daughter’s team.

When he enters all three kids rush toward him, his daughters and his son. So do two dogs, a basset hound and Saint Bernard, who press their noses against his bare legs. Heidi, in the kitchen, asks if he wants lunch before they go. In a few minutes the whole family will head to the airport, bound for Spokane, where his daughter is competing in a 3-on-3 basketball tournament. She’s Heidi’s daughter from a previous marriage, but you’d never guess it. Powers can’t hide his pride for her as he dishes advice. “Don’t eat too much before the game.”

He steps onto the deck. The backyard is a lush fortress of neon green foliage. All this is what he stood to lose in the straits. After a lifetime of hardship compounded by bad choices, Michael Powers finally figured it out—and in the span of a few hours nearly lost it all.

But he didn’t get to keep everything. He lost his best friend, the man who found him at the end of his messy, old life 15 years ago and joined him as he plunged into this one—where a step-daughter hugs you for bringing her sports jerseys, where a Saint Bernard dampens your knee with its snout. The boat accident put it all into sharper focus, reminded Michael Powers of where he had been, how far he’d come.

He can close his eyes and be back in the moment just before it happened. They’re on the water again. It’s dark and cold. The waves—unseen at first, then swiftly illuminated and ghastly—won’t let up. He wants to turn around. Retrace. It seems so much easier. Out of the dark come the words, the stage-whispered guidance from that voice he knows so well. If they try to turn around now, the man to his left says, the boat will overturn immediately. Overturn before the Mayday goes out on the radio. Before anyone can grab a life preserver.

Just keep going, Mike. Keep straight.