The efforts by Woodstock’s original promoter, Michael Lang, to mount a 50th anniversary concert may have ended in disarray, but there are still two upcoming concerts for people wanting to relive the dream.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

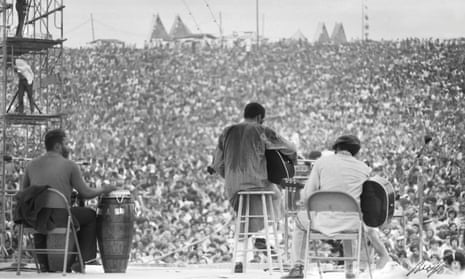

In their own way, they echo the enduring dilemma of the sixties: follow the straight path with an “interpretation” of the epic free-concert; or let your flag fly in a looser, four-day festival that hews closer to the anti-establishment abandon of the 1969, 400,000-strong love-in.

On the site of the original Woodstock, now known as Bethel Woods Center for the Arts, there will be a three-day event fronted by Santana, John Fogerty, Arlo Guthrie and the unlikely figure of Ringo Starr. Up the road hardier types can pitch their tee-pees close to the former homestead of Max Yasgur, landowner of the original Woodstock site, for the Yasgur Road Reunion.

The two are separated by two miles but the differences are stark: Bethel woods, site of the original Woodstock on what was Yasgur’s land is now a lavishly manicured seated concert site, replete with copious concession stands and a museum filled with artifacts from the peace-and-love era.

The Reunion site is far more basic with a stage, a campground and basic amenities for washing and cooking. It’s here, from 15 August to 18 August, that Jeryl Abramson will host an event that, she says, is a truer invocation of the Woodstock spirit.

“It is what it always was – the establishment vs the anti-establishment,” says Abramson, who met her late husband Roy Howard at the ’69 gig. “We’re the anti-establishment staying true to the spirit of the sixties and they’re the establishment staying true to the spirit of the earlier sixties.”

At the Yasgur Road Reunion event, Abramson plans to host two dozen bands, including Melvin Seals and the Gerry Garcia Band and Pink Talking Fish, to as many as 5,000 people, while Bethel’s capacity is 15,000. In contrast, Michael Lang’s now-defunct Woodstock 50 was hoping to get closer to the original’s 400,000.

Since 1985, when she and her husband purchased the homestead from Yasgur’s widow Miriam, Abramson has been waging her own epic battle to stage Woodstock reunions. She points out the difference between the Bethel Woods operation and her own alternative festival.

“They’re preserving the site, and we’re preserving the spirit.” But if all goes according to plan, the two festivals can co-exist.

For the last few months, the drama of Woodstock 50 has dominated efforts to celebrate the festival’s golden anniversary. Lang finally admitted defeat ten days ago, telling the Associated Press it had “not been surprising that we weren’t able to pull this off” after a last-ditch attempt to move the concert to Maryland triggered an artist rebellion.

Meanwhile, the 50th anniversary of the 1969 Woodstock Music and Art Fair will continue in the original punch bowl at Bethel Woods, now reconfigured as a commercialized concert venue owned by cable TV billionaire Alan Gerry. “We are in full-tilt-boogie, as they say,” Darlene Fedun, the Bethel Woods CEO, told the Poughkeepsie Journal earlier this month.

Abramson doesn’t feel bad for Lang exactly, and thinks the fiasco was “perpetuated by his own actions”.

“He did an amazing thing at 24 years old and he should be remembered for that,” Abramson says. “His mistake was trying to out-do what he did last. I feel for him. It was an overwhelming thing for such a young person. I don’t know that anyone could live up to that legacy.”

How far Bethel can go in invoking the free-concert spirit in 1969 is, apart from the advantage of geography, relatively limited. Tickets are limited to 15,000, yet the county is reportedly preparing for upwards of 100,000 visitors to mark the anniversary. Police are warning that only ticket-holders will be allowed within a perimeter set by state police.

The history of Woodstock is almost by definition convoluted. The 1969 festival was held 80 miles from the Catskills town of Woodstock, which has been dining out on its tie-dye association ever since, the town of Bethel has maintained a different relationship.

According to Abramson, Bethel spent “almost 50 years, essentially, trying to forget it happened here and doing things to stop people from gathering freely”.

Meanwhile, Abramson started a 17-year battle for town permits to hold an annual August “reunion”. The ban was lifted in 2013 and permissions were issued for Woodstockers to legally gather at what is known in hippie-speak as “the Farm”.

The shift, Abramson says, came in ’89 when the town’s attitude went from “We don’t want those crazy hippies here” to “How can we make money?”

Nowadays, says Abramson’s son Zack, state bureaucracy has crept into every detail of planning and execution. “Forget about trying to put the show together, the application fee can increase to a quarter million dollars. Unless you have corporate backing there’s almost no way to do it.”

Lighting up a joint at the concert venue could easily be accompanied by a tap on shoulder from a state trooper. At a “Mountain Jam” concert at the Bethel Woods site in June, 11 people, including the front man Adam Ezra Olshansky of the Adam Ezra Group, were arrested, according to state police.

The fact that Bethel police are picking up marijuana smokers speaks to an enduring rift that Woodstock ’69 left in the local community. Police lieutenant Cazzaro told the Guardian the original concert was “poorly organised, dangerous and left behind a mountain of trash”.

So as revelers make their way to Bethel this weekend, Abramson has her fingers crossed that it will turn out well. No brown acid, no trash mountains.

“The Woodstock demographic has shorted out, so now we want to get the message out that there is a better side to Woodstock. We’re open and whatever you wanna do there are places to do it, whether here with us, or Bethel Woods, or both.”