The Comic With the Amazing Technicolor Wardrobe

Julio Torres, the star of the HBO special My Favorite Shapes, brings life to clothing and objects alike: “It feels like my thesis statement is, ‘Everything matters.’”

Picture a stand-up comedian onstage. There’s probably a mic stand, a stool, and a spotlight. The comedian probably jokes, pauses for laughs, and develops a rhythm. Maybe there’s a little pacing back and forth, some physical comedy, a prop or two at the most.

My Favorite Shapes, Julio Torres’s first special on HBO, filters all of that—the very concept of a stand-up act—through a marvelous theatrical kaleidoscope. The comedian, a writer on Saturday Night Live and one of the masterminds of Los Espookys, HBO’s kooky Spanish-language comedy about a group of horror enthusiasts, performs most of his hour-long set sitting in a chair in front of a pastel, Dr. Seussian backdrop. Encircling him is a conveyor belt that delivers objects for him to present in an elaborate show-and-tell. As each “shape” arrives, Torres carefully considers it, holds it up to a camera that projects close-ups on a screen to his left, and offers a backstory.

Some are indeed just shapes with straightforward explanations—a piece of pink plastic with a chipped corner is “a rectangle having a really bad day,” as he puts it—while others are complex dioramas with ornate histories. Torres displays a low-key confidence, a delicate demeanor distinct from the bravado of the type of male comic who prefers stalking the stage during a performance. Eyes often cast downward, he speaks like a wary teacher concerned that his students won’t be able to grasp the lesson in time for the test. “I have a lot of shapes, but not a lot of time,” he announces gravely at the beginning of the special, “so we have to start immediately.”

Known for his off-kilter SNL sketches (oddly specific, often melodramatic fare such as “Papyrus” and “Wells for Boys”), deadpan bits on late-night shows, and his work on Los Espookys (which was renewed for a second season last month), Torres has built a reputation for making high-concept, absurdist comedy–slash–performance art—a Millennial, otherworldly Andy Kaufman by way of Central America. (A decade ago, Torres immigrated to New York from El Salvador to attend the New School, remained in the states on a visa, and just obtained his green card.) “I’m a stand-up comedian, but not just any kind,” he once said as a correspondent on The Tonight Show. “I’m the sort of queer, multimedia kind.”

“When you bring Julio into the equation, there’s … this element of glamour and introspection,” the HBO programming chief Amy Gravitt told me when we discussed Los Espookys before the series’ debut. “It was just a turn I had never seen before that was so delightful.”

But if Torres’s comedy comes off as singular, his style is only more so. He approaches his outfits as meticulously as he approaches his writing. He designs almost every item in his wardrobe, sketching out pieces in the same notebooks in which he jots down bits for his act. When we spoke in June in his Brooklyn apartment, he repeatedly described his work as “purposeful”: He wants his audience to see that he’s put thought into what he wears onstage, and he wants his look to serve as a gateway to understanding his identity, just as his “shapes” allow him to tell anecdotes about growing up an introverted boy in El Salvador. “It feels like my thesis statement is, ‘Everything matters,’” he explained.

In that sense, Torres is the rare stand-up comedian who tests the limits of the genre by deliberately considering and challenging every aspect of his act. “It’s all drag, anyway,” he said of performing. Most male comics put on casual clothing to “present mundaneness,” he explained: “Comedians like the idea of presenting that they were just wandering down the street having their musings and then they wandered onto the stage.” But Torres doesn’t want to express that at all, so he intentionally distances—and defines—himself through his eccentric choices. “Obviously, I’m not just like you!” he joked—sort of. “I’m actually not.”

Take what he wears in My Favorite Shapes, for example. Torres, his brown hair dyed blonde, dresses in a soft, silver, pleated robe jacket and matching pants that shimmer when he moves, with a stretchy white mock turtleneck underneath. He’s covered his hands in glitter, so when the camera zooms in for close-ups of the shapes, his fingers frame each object in sparkles. He looks like a glamorous mad scientist—though Torres told me that he had a different figure in mind. “I felt like I conveyed that I’m, like, this purposeful robot,” he said, “who’s just leisurely doing comedy.”

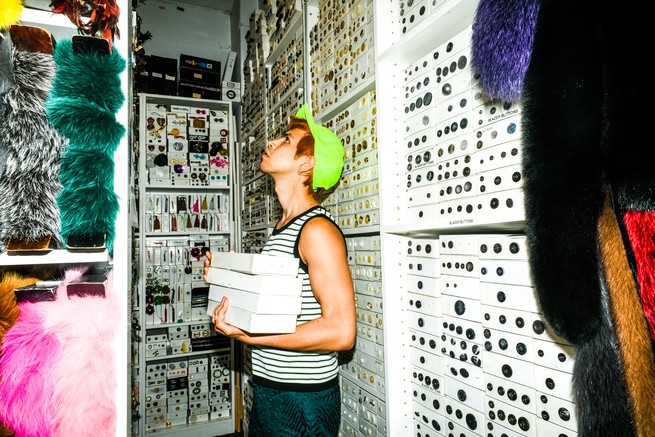

Torres has always thought deeply about the way he looks. His mother, Tita, is an architect and fashion designer who ran her own store, and as a child, Torres “would sketch big horrible princess dresses for her to make and sell,” he remembered. He’d go through phases of self-imposed fashion rules: No jeans, maybe, or no colors other than black and white. Now Torres sketches his designs, purchases the fabrics in Midtown Manhattan, and sends his ideas and materials to Tita in San Salvador, where she takes the pieces to a trusted local tailor to produce. (The long journey is necessary: A typical tailor’s “instinct is to adapt an idea into something they’ve seen before, especially with clothes for me,” Torres said. “Like, ‘Oh no, but a jacket for a man looks like this.’”) If he has a particularly complex idea, he calls on his sister, Marta, also a designer, who enlists her friends to help him with the job. When finished, the outfits get sent back to Torres to try on.

Sometimes—well, oftentimes—they don’t work out perfectly. “There’s a 50 percent success rate that something is going to end up fitting,” he told me. “You end up with a lot of failed experiments. Sometimes the back-and-forth doesn’t feel worth it. Like, this … ” He held up a life-vest-like top with thick black horizontal stripes. “What were we thinking here?!”

The top was one of many Torres removed from the closet inside his new apartment as he walked me through his process. He was packing for the Los Espookys tour, a series of live stand-up shows in New York and California featuring him and his co-creators and co-stars, the comedian Ana Fabrega and the SNL alum Fred Armisen, so he was taking stock of his performance outfits. There’s a delicate sea-foam-green top that frayed after he wore it once, at the Los Espookys premiere; its short life cycle was fine by Torres, since he never re-wears outfits after they’ve been publicly photographed. There’s a heavy blue sweater he wore in a late-night appearance during his “blue” phase. (His favorite colors are “shiny” and “clear,” but every once in a while a shade on the visible spectrum inserts itself into his life.) As he plucked out a pair of bright-orange pants he wore on Late Night With Seth Meyers, Torres noted that orange had been attracting his attention. He’s since dyed his hair the same shade.

Though it’s not the point of his clothing, his visuals do, in a way, bridge his work to his family abroad. Tita and Marta designed the set and furnishings in My Favorite Shapes, and Torres corresponded with them regularly about his outfit. “I liked feeling like I was collaborating with them, and I like celebrating my mom, not because she birthed me, but because she’s a smart, creative person whose work should also be displayed,” he explained. “She deserves as much attention and celebration as I do.”

Plus, the aesthetics can be a shared language between them. “With my mom, the look of it is the part that she can access,” he continued. “That’s the part that she can have an opinion on and can access, because I’m performing in a language she doesn’t know, so she knows how things look. Also, regardless, even if [my set] was in Spanish … I don’t know that [the humor] would be her thing. I guess we’ll never know, but the way it looks is something she understands. Literally.”

Torres’s apartment is blanketed with eclectic, unique pieces. Practically everything in the space could have been a candidate for My Favorite Shapes—his collection of busted clocks would certainly have been worthy—and some were indeed featured on the special. The chair he uses on-screen, designed by his mother and sister, sits in his office; some of the “family” of shapes have been scattered around his desk. He’s still in the process of unpacking and organizing and figuring out what goes where—though he says it’s not necessarily up to him where things end up. A rack for holding a potted plant sits empty on the floor, while the plant it’s meant for rests on the kitchen counter a few feet away. When I asked why, Torres matter-of-factly explained the reasoning: The plant chose to sit on the counter.

He likes to speak of objects not as mere objects, but as beings with identities, with souls of their own. Everything has had a life, however small—and the backstories he offers in the special tend to be as human, vulnerable, and complex as they are funny. A cactus experiences imposter syndrome, while a plastic toy—the kind with liquid perpetually running through it—wants badly to be liked. But Torres’s fixation on the nature of objects has always been evident in his comedy work: A Christmas gift doesn’t have to be just a gift. A sink doesn’t have to be just a sink. A box of items a porn actor finds can help her unlock her character’s motivations. That Torres can find so much to mine from everything around him is rather touching.

It’s also a bit strange, and he gets that. “I live in the real world, and I understand that sometimes a thing is just a thing, and you have to move on, and you just gotta see it for what it is,” he says in the special. “But frankly, I’m sorry, but that is the kind of thinking that got that man elected.” (It’s a rare overt political joke from Torres, whose commentary tends to be more subtle.) And he understands that his process of sketching and corresponding with El Salvador is a lot of effort for assembling a single stage outfit. But again, “everything matters,” so that effort is necessary. He once lugged around a fog machine just to add a dramatic element to his stand-up. When he was performing My Favorite Shapes before it became the HBO special—a special with, by the way, pretaped voice-over appearances from A-listers such as Lin-Manuel Miranda, Ryan Gosling, and Emma Stone—he carried the 50-pound conveyor belt with him to different cities. “It was just horrible,” he explained, “but it’s part of [the show], and that comes first.”

The same goes for his looks. “Comfort is not something I think about at all,” Torres said as he grabbed another top, a short-sleeved and shiny confection, off its hanger. “This is horrible. Touch it.” He was right; it was undeniably rough on the skin. “But I … ” He lowered his voice to a near-whisper. “I don’t care.” Besides, to him, other comedians put in just as much work choosing to wear something less provocative. “Someone steamed that hoodie,” Torres said. “Someone put it on a hanger, someone steamed it, the [director of photography] cleared it for lighting.”

To Torres, the only difference is in the fact that his choices inevitably raise more eyebrows, but “it’s a matter of control,” he said. “I want to decide everything around me, including what I wear.” Still, he acknowledges that experimenting so much with his style may become unsustainable. “I’ve thought about, like, Oooh, would I wear something that someone else designed?” he said. “I don’t know yet. I think we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it.’”

As he becomes more visible, Torres’s comedy—and approach to style—will continue to evolve, no doubt delighting some and baffling others. But before he cracks opens his notebooks to brainstorm new jokes, he has an apartment to finish arranging—there’s a sectional he’s working on designing with his friend, plus that empty potted-plant rack could really use a tenant that prefers the floor over the kitchen counter. The only thing he knows definitively is where his next stage outfit will go once it completes its life cycle: right into his closet, where it’ll stay on a hanger nestled among his other experiments. Once there, “it’s good,” he explained. “It can rest.”