How Pierre Cardin’s Futuristic Fashion Infiltrated Everyday Life

The space-obsessed French couturier has pushed his avant-garde designs, with tremendous success, into houses and closets around the globe.

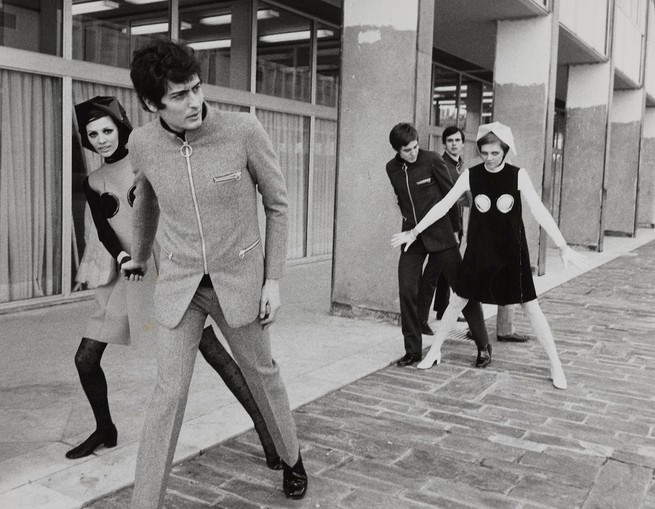

At 97, the French haute couturier Pierre Cardin still conjures designs daily in his office. Since his early career working for noted Parisian houses such as Maison Paquin, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Christian Dior in the 1940s, Cardin’s oeuvre has expanded from refined suiting—the memorable red wool ensemble Jacqueline Kennedy wore in 1961 comes to mind—to otherworldly silhouettes and materials. In 1964, the space-obsessed designer presented his landmark Cosmocorps collection, a pinnacle of mod style with its miniskirts and dresses, geometric details, and one-piece jumpsuit designs. Seven years later, Cardin became the first civilian to don Buzz Aldrin’s Apollo 11 spacesuit, and his extraterrestrial fixation continues.

The retrospective exhibition “Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion” at the Brooklyn Museum—timed to the 50th anniversary of the moon landing—explores the designer’s seven-decade-long career. Cardin’s multifaceted world is on full display: one filled to the brim with oddball space-age fashion, experimental textiles, product collaborations, and licensing opportunities, the latter of which sent his brand globally into homes and closets. Cardin persists today, reifying his vision for newness while predicting a tomorrow in which his designs will serve as a uniform of sorts: “In 2069, we will all walk on the moon or Mars wearing my ‘Cosmocorps’ ensembles. Women will wear Plexiglas cloche hats and tube clothing. Men will wear elliptical pants and kinetic tunics.”

“Future Fashion” uses Cosmocorps as a prism through which to view Cardin’s explorations of gender, technology, and popular culture via his unorthodox silhouettes. (One section is devoted entirely to “bold shoulders.”) While fairly staid in layout, the show comes alive in the penultimate gallery, a room done up in intergalactic style with twinkling LED lights and a Saturn-like halo installation. It features Cardin’s more recent designs, including a number of “Parabolic” hoop-skirted evening gowns that pack flat for travel.

Literal references to outer space aside, Cardin also revolutionized what brand licensing has become today, working with industrial designers to extend his namesake label beyond haute couture and the ready-to-wear market. This is evidenced in the show by the pairing of Cardin’s clothing designs with furniture or smaller household items (including a prototype of a pyramidal television). From the late 1960s onward, Pierre Cardin’s designs went mainstream with brand extensions, a difficult narrative that has remained at the forefront of the house’s history. A simple Google search of the designer’s long foray into licensing shows evidence of the harsh judgments directed at Cardin: “Pierre Cardin’s Demise to ‘Licensing King,’” reads one headline. Another touts the story “Pierre Cardin’s Bizarre Back Catalogue of Licensing,” while the Harvard Business Review offers words of caution with “How Not to Extend Your Luxury Brand.”

What articles of this sort tend not to consider is Cardin’s desire to freely develop his own universe beyond fashion, which he accomplished by entering the lexicon of 1970s and ’80s suburbia as a household name. I distinctly remember encountering the Pierre Cardin brand while growing up in suburban Canada, and at the Brooklyn Museum was instantly taken back to my childhood by two outsize cologne bottles on display, one with a space-helmet-like lid (for men), the other taking a dynamic rose, purple, and black form (for women). For any cultural form to truly transform daily life, it must play a role in people’s lives. It also often means, anachronistically, “selling out” (a concept that became a source of deep anxiety for 1990s alternative culture). But making a buck isn’t mutually exclusive to making art, and the two have always been intertwined, whether hidden or in plain sight.

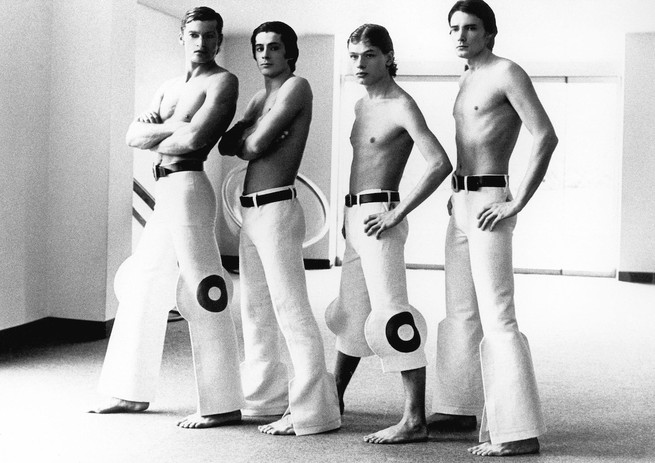

The avant-garde’s interactions with mass culture and consumerism are surprisingly common. Historically, artists and designers have used mass or industrial means of production and distribution as a way of bringing their ideas to the fore. In 1920, the Italian futurist Thayaht had the pattern for his one-piece tuta work suit, which aimed to democratize fashion by providing a single uniform that anyone could wear, printed in copies of the Florentine newspaper La Nazione, hoping readers would replicate the design at home. The modest men’s shirting, tasteful belts, and neckties Cardin sold in chain department stores both represented and funded his forward-thinking ways. These were affordable and wearable alternatives to his other, more experimental designs: wacky men’s linen pants with bulbous knees from 1972, say, or a men’s silver vinyl vest, shaped like an inverted triangle, that exposes much of the torso, from 1994. (This attention to the popular also extends to Cardin’s early designs for the Beatles and his costumes for The Avengers television series.) Cardin’s mission of influence doubles as a philosophy to dress all.

The average person may never wear a space helmet, or a black velvet evening dress with a Swarovski-crystal-encrusted, orbit-shaped sleeve, or an LED-lit jumpsuit (all on view in “Future Fashion”), but likely will have seen the Pierre Cardin signature emblazoned on any number of products. In this way, Cardin, working steadily for decades, has made a twofold contribution to style: pursuing his avant-garde work on the high end and making his name known in homes around the world on the other. Either way, he imagines a tomorrow where his designs will be worn and used by all.