HBO Max’s Golden Ticket

The details of the newly announced mega-service are murky, but it has one huge advantage over Netflix: the streaming rights to Friends.

As media conglomerates prepare for the next age of streaming television, it appears the most pivotal branding choice is the suffix. What punchy addendum do you tack on to your company name to suggest something new and exciting is in the offing? Disney and Apple went for a plus sign, as they spool up their Netflix competitors Disney+ and Apple+. WarnerMedia, which plans to pull together its ample TV and film libraries for one big umbrella package, is going with “HBO Max,” promising that its most recognizable channel will grow to gargantuan size. (NBC/Universal’s service is as yet unnamed; perhaps it can be called “NBC Ultra,” or maybe it’ll just add an exclamation point.)

HBO Max is the end result of AT&T’s multibillion-dollar acquisition of Time Warner, a move the telecom company said would help it compete with the tech giants that are muscling their way into the media world. The newly branded WarnerMedia—which includes HBO, the film studio Warner Bros., the cable-TV titan Turner Broadcasting, and a hundred-year-old archive of movies and television—is no longer interested in boutique operations. Services as disparate as the arty streaming archive FilmStruck and the venerable font of satire MAD magazine have been dissolved by WarnerMedia in recent years. Most surprising of all was the WarnerMedia CEO John Stankey’s edict to HBO that it had to start making more shows to compete with Netflix.

The message was poorly received by veteran HBO employees, who were essentially being chastised for producing one of the most trusted brand names in entertainment through careful curation. HBO’s longtime head, Richard Plepler, left the company in March. The future, according to WarnerMedia, will be one of greater scale: HBO Max will offer “10,000 hours of premium content” by bundling HBO, TNT, CNN, Cartoon Network, Turner Classic Movies, The CW, and the Warner film library. Details aside from that remain scarce, and the price is unknown (though early reports pegged it around $16 or $17 a month).

The initial announcement earlier this month was greeted with confusion by some industry analysts, given how crucial the price point is and the fact that (non-Max) HBO will remain available to cable-TV subscribers via services such as HBO Go and HBO Now. The AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson tried to clarify how the company will move forward and preserve its relationship with traditional cable operations while entering the streaming space, but the path forward is murky at best. Such is the nature of “old media” trying to transform into something newer and nimbler.

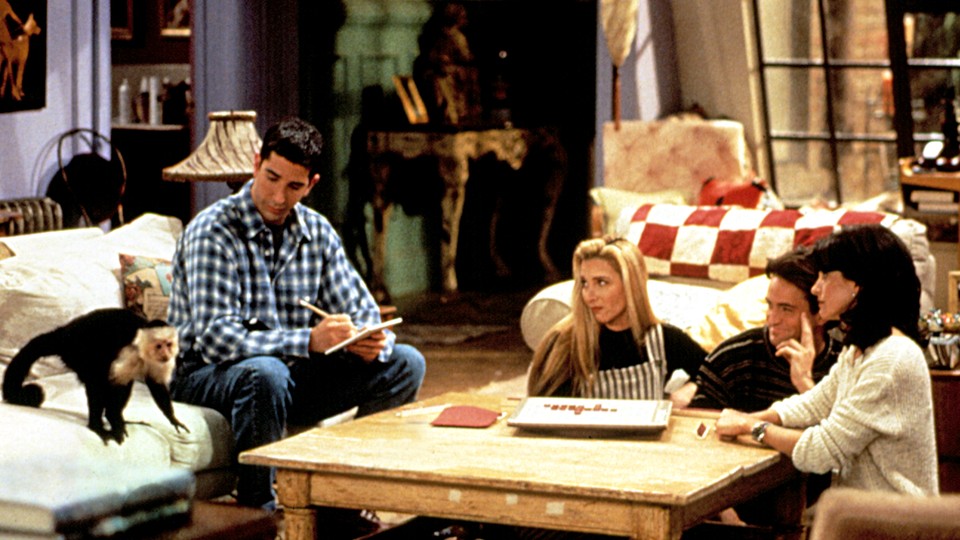

What better example of that clash between old and new than the pitched battle for control over Friends, a Warner Bros. TV series that hasn’t aired a new episode in 15 years but was touted by WarnerMedia as the crown jewel of HBO Max starting in 2020? Warner’s streaming division paid a reported $425 million to its TV division for the streaming rights to the show for five years, a staggering total that’s a testament both to the sitcom’s continued popularity with younger generations and to WarnerMedia’s desire to land a blow against Netflix, which paid Warner TV at least $80 million to house the show in 2019.

The incredible sums Netflix was willing to spend on Friends would’ve been oodles of easy profit for WarnerMedia every year. But WarnerMedia is instead essentially paying itself (more precisely, one division of the conglomerate is paying another) to invest in its streaming future. NBC/Universal, owned by Comcast, is doing the same thing with The Office, another long-finished show that became a syndicated favorite for Netflix. The series will move to NBC/Universal’s planned streaming service, which is yet to launch, in 2021 for the price of $100 million per year (Netflix reportedly offered $90 million).

Both of these departures were tearfully announced by Netflix’s social-media accounts, as if the company were saying goodbye to its own original programming. The amusing irony is that both Friends and The Office are readily available for purchase, as DVDs or as digital copies on iTunes, for viewers to own forever and watch whenever they like. But on a service like Netflix, these shows filled the same role that beloved sitcoms have since the dawn of television—they’re easy, comforting fallback options for when you just want to have something on.

That’s why WarnerMedia’s confusing rollout for HBO Max might not end up mattering much. Even though it has the name of a decades-old cable channel and is being launched with old TV episodes, that may be enough to get subscribers on board. The branding might change, and the pricing structures remain in flux, but people still want to watch an episode of Friends before they go to sleep. That familiarity is what WarnerMedia is banking on.