The saxophone has long been a staple of the jazz genre and, for a lot of people, the soothing tones of John Coltrane or Charlie Parker will remain as the defining sound of the instrument. Since then, however, the sax has been subject to much change; artists such as Joe Henderson and Jackie McLean pushed what boundaries they could in their personal explorations. And more recently, the name Shabaka Hutchings has resonated as another pioneer within jazz; the British-Barbadian saxophonist subscribes to no one method of playing his instrument. Either as a solo musician or with one of his three current bands, Hutchings is constantly revolutionising the UK jazz sound. Finding inspiration everywhere, from soca music to Nipsey Hussle, the saxophone holds limitless potential for this classically trained musician.

Last year, Sons Of Kemet, the British jazz four-piece, struck gold with their critically-acclaimed full-length debut, Your Queen Is A Reptile. The project sought to question the hierarchies within society by suggesting alternate queens, protagonists of black history and inspirations to the band. The iconic saxophonist’s future-forging band, The Comet Is Coming, more recently dropped Trust In The Lifeforce Of The Deep Mystery, which is as much sci-fi as it is jazz, with Hutchings at the helm. And then there’s Shabaka & The Ancestors, a more spiritually-led project that pays homage to their African roots.

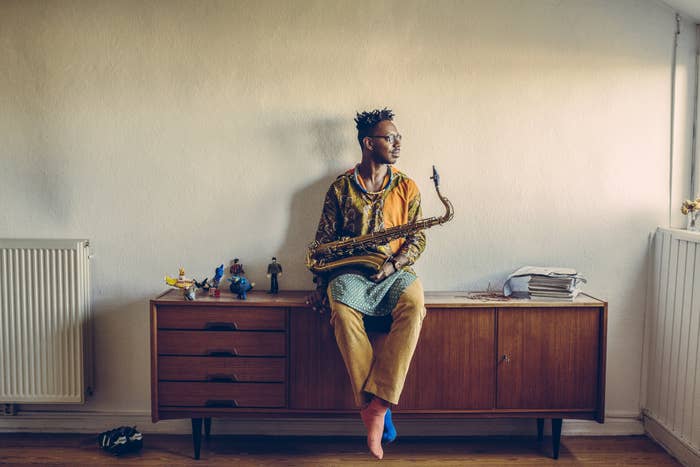

It’s fair to say that without Shabaka Hutchings, the UK jazz scene would be missing a vertebra in what is an incredibly strong musical backbone. We caught up with him to gauge his own perspective on music, as well as the journey and the many experiences that have led him to where he is today, right before he performed at Somerset House with Sons Of Kemet.

COMPLEX: How has 2019 been for you so far?

Shabaka Hutchings: It’s been great. Last year was focused on more Sons Of Kemet, with Comet Is Coming doing specific gigs. This year has been more focused on Comet Is Coming because of the album. It’s been good to get a different outlook on music making through Comet Is Coming because it’s a bit more punky and a bit more rock-based; it’s a different persona that I embody with Comet.

Who or what would you say were the biggest influences on your playing style?

That’s a tricky one because there’s not one particular person or type of music that is a massive influence. I get influence from different things and different periods in my life. So it might be that at certain periods, someone like John Coltrane is a really big influence, but it also might be that someone like Fela Kuti is that for me at a different period. At the moment, I’m listening to lots and lots of Nipsey Hussle, and I’m listening for specific things.

How exactly does Nipsey Hussle inspire you?

In a bunch of different ways. One, is just the way that he flows. If someone’s rapping with a certain swag or a certain attitude, it’s not necessarily what they’re rapping about, or how they’re even rapping, it’s just the attitude they approach telling the audience something. Even just Nipsey’s approach, almost like his demeanour and how he carried himself as someone who was successful and really wanted to push forward... For me, you know, I’ll be on stage, like, fighting the battle of music, trying to go as hard as I can. And that’s why I’m inspired by Nipsey Hussle and his journey: he proved that you can always go harder, and try to go as far as you can in this thing. It’s up to you how far you think you can go as a human being, or as someone from a historically marginalised background—you just have to break forward.

That’s the thing I think I appreciate the most about classical training: how to forget about my personality and learn how to be an interpretive machine, and through that, I believe in my own emotionality.

Aside from individual artists, your music is a culmination of cultural influences. What cultures would you attribute to your sound?

Yeah, I mean, I grew up in the Caribbean, so the most obvious one is the Caribbean—soca and calypso culture—and, in terms of that, it’s a lot to do with a level of hype, so if you go to see someone like Capleton or Buju Banton, or some calypsonians and soca musicians like Machel Montano or Alison Hinds, the thing that they’re trying to get the crowd to is a level of hype and energy. When they come onto the stage, they just want the crowd to lose themselves, to stop being restrained. It’s almost like being restrained is a trap; it’s something that we’ve learned to do that is separate from Afro-Caribbean culture, and it feels like the role of the musician is to remind people that ‘this isn’t what you’re supposed to be doing! You’re not supposed to be restrained—you’re supposed to lose your shit!’

It’s like, how do you do that as a musician, especially as a musician that doesn’t use words? You can’t tell people to just get up and lose it! It’s like certain musical signs and symbols within the saxophone or within a certain language to do with jazz might inform people and make them lose it. Other than that, hip-hop culture has had a big influence—it’s what I grew up with in the ‘90s. I grew up listening to Nas’ Illmatic, Biggie’s Ready To Die and the Lost Boyz. That’s had a big influence, in terms of it’s a big conversation, but in the way that I see non-instrumental musicality. When I hear rappers—in some ways, I try to forget about what they’re saying and see what they’re doing as musical by using words as music. It’s made me consider what I do on the saxophone in a different way, in terms of being able to take influence from these groups of musicians. I listen to a lot of music from around the world every day—that’s my thing: I try to listen to as much music as I can. It might be at one point I’m listening to a lot of Bulgarian flute music, or at one point I’m listening to Gamelan from Java.

A lot of the times, the way influence works is that if I hear something that I like, I listen to it a lot and then when I’m in the heat of the moment playing or composing, something might come into my head formed by a certain cultural influence. I do think that one of the tricks to influence is not to see it as influence; once you start to see yourself as being influenced by something, then it means that you start to define the thing. If I say ‘I am defined by Caribbean music’, it means that I’m gonna start to define Caribbean music for myself. I think everything is deeper than we see on the surface, so Caribbean music isn’t what I define Caribbean music as—all I can do is start a process of trying to see Caribbean music in as many different ways as possible and then maybe I can get something from my way of perceiving the contributions of these musicians.

Other than the obvious answers, what would you say are the differences between classical training and other ways of learning?

That’s an interesting question. I think coming up through classical training allows you, as a musician, to be versatile. That’s not impossible if you don’t have classical training, but it might be harder, so for instance: if you come up playing in bands, it’s very easy to be a really proficient musician in the music that you’ve surrounded yourself with directly. This does stretch you, but it’s not outside of what you started playing. The thing that I learned playing classical music is almost how to be a machine. If someone puts a piece of music in front of my face and says “this is the style you’ve got to perform in” and it’s not necessarily something that I define myself as, it’s about me training to learn how to be a vehicle for someone else’s musical vision—and that could be in any age, from the 1700s to last year. That’s the thing I think I appreciate the most about classical training: how to forget about my personality and learn how to be an interpretive machine, and through that, I believe in my own emotionality. Learning how to do that doesn’t do anything to my individual vision of music or personality because that’s who I am, but everyone has a different journey through music.

When I left music college and was trying to earn a living as a musician in London, it meant that I was able to work in a lot of settings that maybe you wouldn’t be able to if you didn’t have that that kind of training; I might be able to go and work in the West End, or do some work with an orchestra or film soundtrack stuff, whatever. I can read really well—I can carry myself as a trained session musician. It’s got its drawbacks because not everyone has the same trajectory as me. I was going to jam sessions and just doing as much playing as possible in all different kinds of scenarios. I know a lot of musicians that get stuck in the classical way of playing or approach to music, because there’s the whole hegemony thing attached to classical music where they’ll say explicitly and otherwise that it’s better than all other kinds of music. If you can get through that rigidity and that cultural imperialism, then you’ll be a really good musician and you can take from that culture. The problem is that classical culture takes a piece of you that isn’t given back by any means.

Your Queen Is A Reptile. What did the album mean to you?

For me, that album was a snapshot of what myself and the people around me had been thinking about at the time, so it wasn’t as dramatic as it might have been to the external listener. For me, this is what we talk about, this is what’s in the air right now, conversations are still going on and the issues are still present. The issue is not the Queen and it is not the reptile—it’s about structures of symbolism that define how power is seen throughout society and how we relate to it.

What did you think of the reaction to it?

It received a great reaction, but in some ways, I thought there’d be more of a kickback because we’re in Britain and saying Your Queen Is A Reptile. But we really didn’t get a lot of negative feedback. I think one of the reasons for that is that I made a big effort to really articulate what we mean by saying that, and what the album’s about. I’m not a big believer in putting out cryptic messages and leaving it to the audience to figure out what we mean. History is gonna be recorded by somebody, so unless the artists do it for themselves, or lead the public down the search and the route of thinking, then your words or what you mean can be manipulated. So I try to do as many interviews or be as expressive and as articulate in the interviews as possible. If someone goes “what do you mean your Queen might be a reptile?”, they can get an explanation which doesn’t necessarily make them agree, but makes them go: “I see what your perspective is and I see what facts of life have led to your perspective.” For me, this is how society has reached some kind of equilibrium: by people not necessarily saying I agree with every single person out there, but saying that they empathise or see how perspectives can differ. And then, from that point, we can start to make compromises.

What does your ‘anarchist approach to music’ with The Comet Is Coming entail?

The anarchist approach is basically just we all have to achieve autonomy—we all do whatever we want to do, and that was how the music was formed. Doing whatever we want to do doesn’t mean that there’s chaos; we’re not all operating in a bubble separate from each other. We appreciate that we make music within a system and a network that relies on everyone being sympathetic and listening, so I might have the freedom to do whatever I want to do, but if what I decide to do jeopardizes the role that the drummer or the keyboardist has, then everyone’s going to suffer. It’s an amount of respect and vulnerability almost to make it work. That’s something we’ve had from the beginning, and it has had its challenges; it’s not easy. If someone is doing something that you don’t like, it’s about trusting that they’re also trying to make the music the best it can be and it’s just a journey towards good music.

It’s up to you how far you think you can go as a human being, or as someone from a historically marginalised background—You just have to break forward.

I had the pleasure of seeing you at Cross The Tracks a little while back. What is the key to your unique live performances?

Well, we do a series of breathing exercises before we play. At this stage, I do it before we play any gig, but we started it with Comet Is Coming. The breathing exercises were influenced by a guy called Wim Hof, and what it does is it gets us on to a similar wavelength in terms of energy and in terms of all being focused on the communal aspect of music. I don’t know how it works, technically, all I know is that it works! When we do it, we might be running around on all different kinds of wavelengths, but then we get together in a circle and we do this exercise and it brings us all into one energy. From that, we can then go on stage and try to lift the energy on stage and in the crowd as much as possible.

For all its listeners, Brownswood’s We Out Here was a confirmation of the incredible young artistry happening right now. What did it feel like to be a director of such a project?

It was really easy. All the players are in working bands, so they all know what type of music they’re trying to get across; they know their vision. My role was just to make sure that the vibe in the studio was okay, and in most cases, it was completely fine—we didn’t need to do anything—it was just to make sure everything’s running smoothly, and that no one’s getting stressed out by one section over another. This is a period where bands are understanding what they need to do in relation to the audience so when they go into the studio, they all give a lot, and get a lot back.

What would you say are the limitations, if any, to the jazz scene right now?

It’s tough to say because you never know until you look at it from hindsight. There are things that I could say are limitations—you don’t know how musicians progress. For instance, a lot of the music being played now is modal-based and groove-based. That can be limiting in that three, four albums down the line, it could get to a point where everything kind of sounds the same, but then again maybe it’s not gonna sound the same. Maybe we’re gonna find a way to develop the music that everyone loves now into more and more creative stuff. The thing with creation is that you have to be at a point of having nothing to get something. You have to get at a point where everything that you think could go wrong with the jazz scene is nearly there, and then someone decides to take another path.

So is that the key to furthering the jazz scene?

Yeah, it needs to get to that point where it could be where acid jazz reached, which became a bit boring after all the celebration and hype wears off. But at that point where it starts to become boring, is the point where musicians can push through and say, “No, we need to creatively find a way to further the music.” It takes going to that edge, to that limit, to make artists really reach within themselves and decide what they want to do, what’s the function of the music on a big, macro level.

How does it feel to be signed to a label like Impulse? What does it give you?

It feels great. What it gives us, in practical terms, is a well-oiled machine. We work on the music, I compose, we rehearse and get it to a position and record it. What we want at the end of that is the machine that puts it out to the ears of the listeners. On another level, it’s really great to be a part of history, a part of the tradition that goes from John Coltrane to Pharaoh Sanders to Alice Coltrane. It’s something that contextualises the music and almost gives validity to what we’re doing. At no point are we trying to be Impulse artists—we’re just being ourselves and this validity has been given to us through the association of Impulse.

What would you advise other artists who want to follow in the same footsteps?

No. I think everyone needs to find out what’s right for them. There’s no clear cut way of doing anything in the music industry; it’s all about what works for the individual artist. It’s about if they’re conscious about doing it. For me, the thing to watch out for is are you conscious or unconscious? Are you signing for a big label because someone else signed for it, or is there a reason why you’re going down this path? There are a lot of benefits of staying independent. I love the idea of staying independent, and I would if I thought that was the best thing for me, and us. But at a specific point, just before the Sons Of Kemet album came out, I think signing to Impulse was the right thing to do—especially in terms of broadening the base in America, in terms of getting something that means, globally, people perceive the music in a different way. It shouldn’t be like that—it should just be about the music—but unfortunately we live in a world where the symbols and what things mean are based a lot in the psyches of people, so I did it [laughs].

How important would you say the US is for not only your music, but these other young jazz musicians?

It depends on where the artist is. America is important because it’s one of the big markets in the world; it’s got loads and loads of people and a structure of music, creation and production, that’s been there for a long time and knows what to do with artists once they’ve shown that they can play the game and have something to offer. This is the first period, however, that we’ve been going at it hard, over the last year in America. I only went to America for the first time four or five years ago, which was with Melt Yourself Down at SXSW, and again at Floating Points. Even up until about two to three years ago, it was just the odd gig here or there, but we were trying to refine what we were doing in England and Europe, and that was fine.

There has never been, in my head anyway, a pressing need to go to America, but if the opportunity is there and it’s the right time, then that’s great. It’s a logical progression. But for me, it can be something that’s in the front of your head as an artist’s endpoint and ultimate goal; for me, the ultimate goal is music, to make as articulate a musical statement as possible, have it be presented in a way that resonates with people and does to them what you want it to do. Once you’ve got that, you want to spread your music as much as possible, and if that means taking it to America, then it can happen and it’s great, but even if it doesn’t it’s no big concern.

What can we expect to see from you in the near future?

Well, we just finished the new Shabaka & The Ancestors album, which should be out at the start of next year, and we finished recording the new Sons Of Kemet album but that still needs a lot of production so that’ll also be out next year.