Why Google Maps Has a Fraud Problem

Google corners the search market with 63 percent of all queries on the web(Opens in a new window). You might've even expected that number to be higher given that Microsoft garners almost all of the rest and people have a genuine bias against Bing(Opens in a new window). Despite growing issues of trust(Opens in a new window), almost two-thirds of the world still chooses Google for search and Chrome as their browser(Opens in a new window). With clear dominance in the search market, the company's platform is an ideal target for fraud in the same way viruses and other exploits target Windows systems more than any other. When you want to find the largest pool of victims you start with the largest group of people.

Nevertheless, Google's efforts to combat the fraud on its platform appear minimal and mostly ineffective. The Wall Street Journal recently broke a story accusing Google of profiting over millions of fake and fraudulent listings(Opens in a new window) on its platform, but what seemed like news to many should have felt like déjà vu. This has been very public knowledge for over five years(Opens in a new window). More than half a decade ago, cybersecurity expert and hacker Bryan Seely(Opens in a new window) used an exploit in Google Maps(Opens in a new window)' business listings to change the contact numbers for the FBI and Secret Service to wiretap their calls. He successfully recorded 40 calls in a single day using this process in order to demonstrate the problem to the government. The government listened, told Google to stop, Google did, and then it started back up again three months later.

Five years later the WSJ tells the same story from another perspective: the victims affected by it. Here's a sample:A man arrived at Ms. Carter’s home in an unmarked van and said he was a company contractor. He wasn’t. After working on the garage door, he asked for $728, nearly twice the cost of previous repairs, Ms. Carter said. He demanded cash or a personal check, but she refused. “I’m at my house by myself with this guy,” she said. “He could have knocked me over dead.” The repairman had hijacked the name of a legitimate business on Google Maps and listed his own phone number. He returned to Ms. Carter’s home again and again, hounding her for payment on a repair so shoddy it had to be redone.This is hardly an isolated incident(Opens in a new window) and, as the WSJ also points out, Google has acknowledged the problem:

Mr. Russell, of Google, said the company removed more than three million false business listings in 2018. The company last year also disabled 150,000 accounts that uploaded the made-up listings, he said, up 50% from 2017. Google didn’t detail its countermeasures, citing security.As noted(Opens in a new window) by TechCrunch, Google responded to the WSJ article with the following information(Opens in a new window):

In the company’s response, Google Maps product director Ethan Russell wrote that of the more than 200 million listings added to Google Maps over the years, only a “small percentage” are fake. He said that last year Google took down more than 3 million fake business profiles, including more than 90% that were removed before users could see them. Google’s systems identified 85% of the listings removed, while 250,000 were reported by users. The company also disabled 150,000 user accounts found to be abusive, a 50% increase from 2017.

If that text seems familiar, it might be because Google recycled the same information the WSJ cited in their article. While Google hasn't resolved to do nothing at all, the effort it put into combatting fraud on its platform rests in a delicate balance between ethics and profit—two things that, currently, do not align in many areas of Google's business.

Google has also received criticism for failing to police click fraud on advertisements(Opens in a new window). Meanwhile, it has been accused by many of squashing the competition(Opens in a new window) to maintain the market dominance that allows them to act in this manner. It has entertained numerous class action lawsuits(Opens in a new window) as well as other notable litigation(Opens in a new window) involving these and similar issues. The company remains under constant fire for its questionable privacy practices and continued willingness to profit off the victimization of its users. After all, in 2018, Google earned $116 billion in advertising revenue alone and stopping many of these issues would cut into those earnings.Why Google Can Legally Profit from Fraud on Its Platform

It might seem illegal for Google to profit from millions of fraudulent listings and do practically nothing about them but it's not—and in some ways, that's a good thing. Section 230 of the US legal code (formally 47 U.S.C. 230(Opens in a new window)) protects Google and any other company that operates an online platform, from legal responsibility for the activity of users on that platform. Derek Bambauer(Opens in a new window), professor of law at the University of Arizona, explains:The real action is in 230(c)(1), which says that no provider (e.g., Google) or user (maybe also Google) of an interactive computer service can be held liable for content created by another information content provider. (Both "interactive computer service" and "information content provider" are defined in Section 230.) So, if I put up a review of your restaurant on, say, Yelp, that falsely claims the place is overrun with cockroaches and rats, Yelp is immune from getting sued for defamation. (You can still sue me, of course -- I'm the information content provider.) This remains true even if Yelp knows that the review is false.

An online platform makes it more difficult to catch the originators of the fraudulent activity and that leaves little legal recourse for affected consumers and business alike. As Bambauer puts it, "suing Google is definitely like tugging on Superman's cape: probably not one's smartest move. Google has a fleet of extremely good lawyers. Google is going to win. The best option businesses have is to start a fuss and put public pressure on Google." Unfortunately, as we've seen, public pressure at the level of TED talks and Wall Street Journal articles only illicit a recycled response from Google.

Section 230 acts as an almost impenetrable legal wall with very few notable exceptions: trademark violations and the FOSTA-SESTA amendment(Opens in a new window) that exempted instances of sex-trafficking. While the latter may sound like a good idea on the surface, the amendment broadly defines the circumstances in which a company bears responsibility for the content on its platform. In response, many companies (such as Craigslist and Tumblr) completely removed and disallowed any and all sexual content(Opens in a new window). Many have also argued that the amendment endangers sex workers(Opens in a new window) and does little to solve the sex-trafficking problem.

Meanwhile, more prevalent issues like fraud have not motivated lawmakers to amend Section 230 further. Doing so would likely lead to companies shutting down even more significant parts of their platform that aren't mired in the social politics of human sexuality. Without careful consideration, amendments to Section 230 can act as an on-and-off switch for what we're able to do online with consequences that span the globe. If we want to protect internet freedom we have to protect Section 230, but by doing so we're also allowing companies like Google to legally profit off of massive amounts of fraud.

The current situation also incentivizes companies to do less to avoid creating new liabilities. For example, while Section 230 does not protect online retailers from product liability claims(Opens in a new window) (e.g. exploding cellphone batteries), Amazon uses its marketplace to sidestep that problem. After all, the company doesn't directly sell the product to the consumer but simply takes a cut from the business that does. This issue became more complicated recently when a lower court decided Amazon could share liability for defective goods sold by a third party—but only if they warn consumers of the problem(Opens in a new window). For Amazon, choosing the more ethical option of warning consumers could cost it millions in mandated refunds.

Google may face a similar problem. The more effort it takes to warn consumers about the dangers of fraud on its platform, the more it risks creating a legal vulnerability that can circumvent the protections provided by Section 230. Furthermore, any solution to the problem—in part or in whole—directly affects Google's earnings and it has an obligation to its shareholders as a publicly traded company. This creates a complicated set of circumstances that encourage Google to continue with its current behavior. They attempt to develop better methods of automatic detection to root out fraud in advance and rely on users to report anything that gets missed. Doing more could result in an enormously negative impact on their business.What Google Can (and Should) Do to Help

Should legal complications absolve Google from further responsibility? Is it ethical to operate and profit off of a platform that can cause significant harm to a large number of its users? While it might feel simple to reach an ethical answer to this dilemma, reality poses the far more difficult problem of solving it. If Google attempts a solution that's vulnerable to costly litigation, it might lose the financial resources necessary to reach an effective solution. In a worst-case scenario, this would lead to the end of Google Maps.

While extreme results like this seem highly unlikely, we saw a massive shutdown of internet services when FOSTA-SESTA became law. Companies didn't wait for legal action to arise but rather shut down preemptively. Google has already threatened to shut down its news service over the EU's passing of Article 13(Opens in a new window) (later renamed Article 17) due to potential costs.

Regardless of what could happen, Bryan Seely argues that Google still has options:It is not in Google's internal best interest to find all the spam 100% of the time as it becomes really time consuming on a large scale with a lot of ambiguous/difficultly to determine listings. Some are obvious, others are not. Google should be interfacing and helping various countries and states to develop a "legal" or "not legal" business database API so that the entities like Department of State that gives business licenses gets checked when a business is online. The reason we issue licenses like that to organizations is for accountability and protection of consumers; this is almost a complete circumvention of that process.

For this to work, Google and the Government would have to work together. Additionally, Google could provide contextual tools for reporting fraud. For example, take this basic search for an electrician:

It's worth noting that at the most common screen resolution 1280x800(Opens in a new window), you will only see ads in your results unless you scroll. But let's take a look at the first option and how that business fares on Yelp:

If this company commits fraud, how would you report the problem to Google? Each search result has a little menu that's easy to ignore, but even that doesn't provide the option:

You can learn why you've been shown the ad but you can't report it directly from the only contextual option available to you. Furthermore, Google leaves a lot of literal room for providing helpful tools for its users:

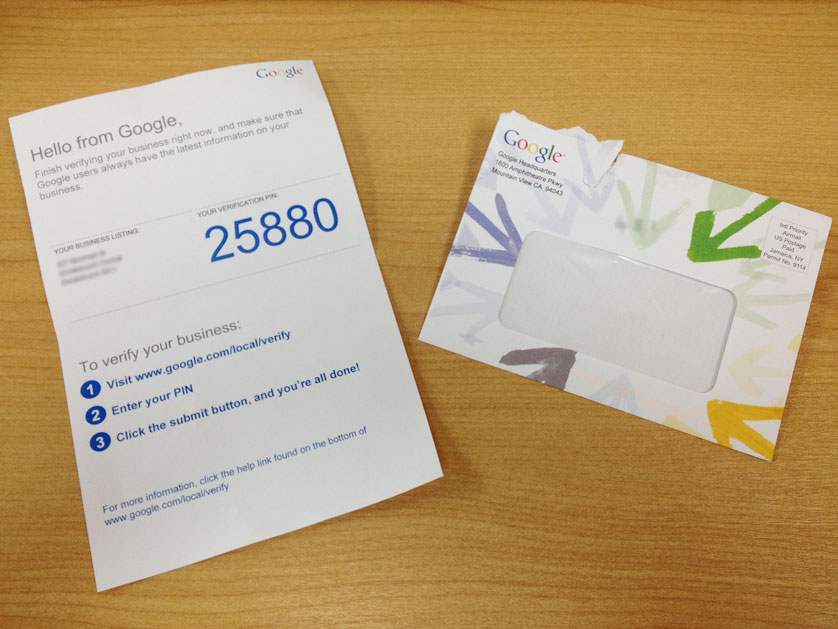

Google doesn't have to create liability by warning you of potential fraud and can simply display a link to information it already publishes about how to protect yourself and report an issue. Meanwhile, the company's most significant verification effort involves mailing a postcard to the user who wants to claim an address and publish a listing. By setting up mail forwarding, practically anyone could reroute mail from the address of an existing business to themselves to take over that address on Google.

The same process works for creating new listings. Seely estimates that an individual could fashion hundreds of fake listings per day. I attempted the process (without finalizing it) myself and it took under five minutes on my first try. That's 12 listings per hour, or 84 per workday if you take a long lunch break. With some practice, and perhaps help from account generators easily purchased on darknet marketplaces for as little as $10, it's not hard to see how a dedicated person could manage hundreds of fake listings every day. Even using a manual process you'd surpass 100 listings by putting in a little overtime.

Google could make the effort to institute better verification processes, such as the one Bryan Seely suggests, but it's hard to believe it will make the effort when it doesn't even bother to print DO NOT FORWARD on its verification materials (pictured above).

While Google will likely never eradicate fraud on its platform, and it's unclear which additional methods would help the most, it's abundantly clear that Google has spent at least half a decade ignoring worthwhile efforts that do not create further legal liability for the company. While it isn't fair to assume greed as Google's sole motivation, its behavior demonstrates a preference for profit over customer protections in several specific instances.What You Can Do to Motivate Google

Complex, widespread problems torture us in the news on a daily basis and trust in mass media continues to decline(Opens in a new window). Even when you can believe what you read, hear, or see, it can feel like there's nothing you can do about large and complex issues like this one.

While combatting online fraud will take a lot of work from a lot of people, small efforts from all of us can inch us closer to a safer online experience for everyone. Here are some options to consider if you want to try and help Google do the right thing:

While combatting online fraud will take a lot of work from a lot of people, small efforts from all of us can inch us closer to a safer online experience for everyone. Here are some options to consider if you want to try and help Google do the right thing:

- Report fraud and other scams when you see them(Opens in a new window). You don't have to be a victim to do this so long as you're reporting a business based on evidence (that's often easily found online) and not assumption.

- Tell Google to implement better solutions, like those discussed in this article, by sending in your feedback. One message won't matter on its own but many messages from users can. You can also tweet at Google Maps(Opens in a new window) with regularity to encourage them to address these issues further. Even with no reply, that tweet exists in public and will be indexed by search engines and that can, at least, increase recognition. (Google Maps also has an Instagram account(Opens in a new window).) You can also send feedback about problematic search results(Opens in a new window). You can even send them physical mail at 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway Mountain View, CA 94043—something you can do without leaving your computer(Opens in a new window). You have a lot of options(Opens in a new window).

- Contact your senators(Opens in a new window) and encourage them to address this issue intelligently by working with Google to create a better business verification system. If Google makes the effort, other businesses with similar (but lesser) problems will follow suit in order to remain competitive.

- Talk about this problem with people you know—especially the less tech-savvy who may not have the knowledge and experience to recognize fraudulent listings in advance. Practically no one trusts what they find on the internet(Opens in a new window), but (as previously mentioned) people put a surprising amount of trust in Google nevertheless. It's necessary to understand specific issues surrounding specific types of activities when you want to protect yourself online. Share that knowledge with others so they can do the same. You can share an article like this one, but you'll accomplish more with a face-to-face conversation.

It may take a while, even with so much exposure, but if we continue to put pressure on Google to make more of an effort to fix this problem we can improve this situation. These are just small ways anyone can help, but people like Mark Baldino(Opens in a new window) have put more significant efforts into combatting this issue. You should do what you feel is right. If you have another positive way to help motivate Google to reduce the fraud on their platform, please share it in the comments. We only have a chance at making this better with our combined efforts.

Special thanks to Bryan Seely(Opens in a new window) and Derek Bambauer(Opens in a new window) for their contributions to this article. Top image credit: Adam Dachis Now read: