When was the first time you heard of Kanye West?

Many of us were introduced to him as the guy who rapped through a wired jaw on “Through the Wire” in 2003. Other listeners who voraciously read through credits might have noticed that he produced multiple tracks on JAY-Z’s 2001 classic, The Blueprint, or even the Hov ballad “This Can’t Be Life” from the year prior.

But years before Kanye became a rising star in music and a go getter in several industries, he was actually a Go Getter.

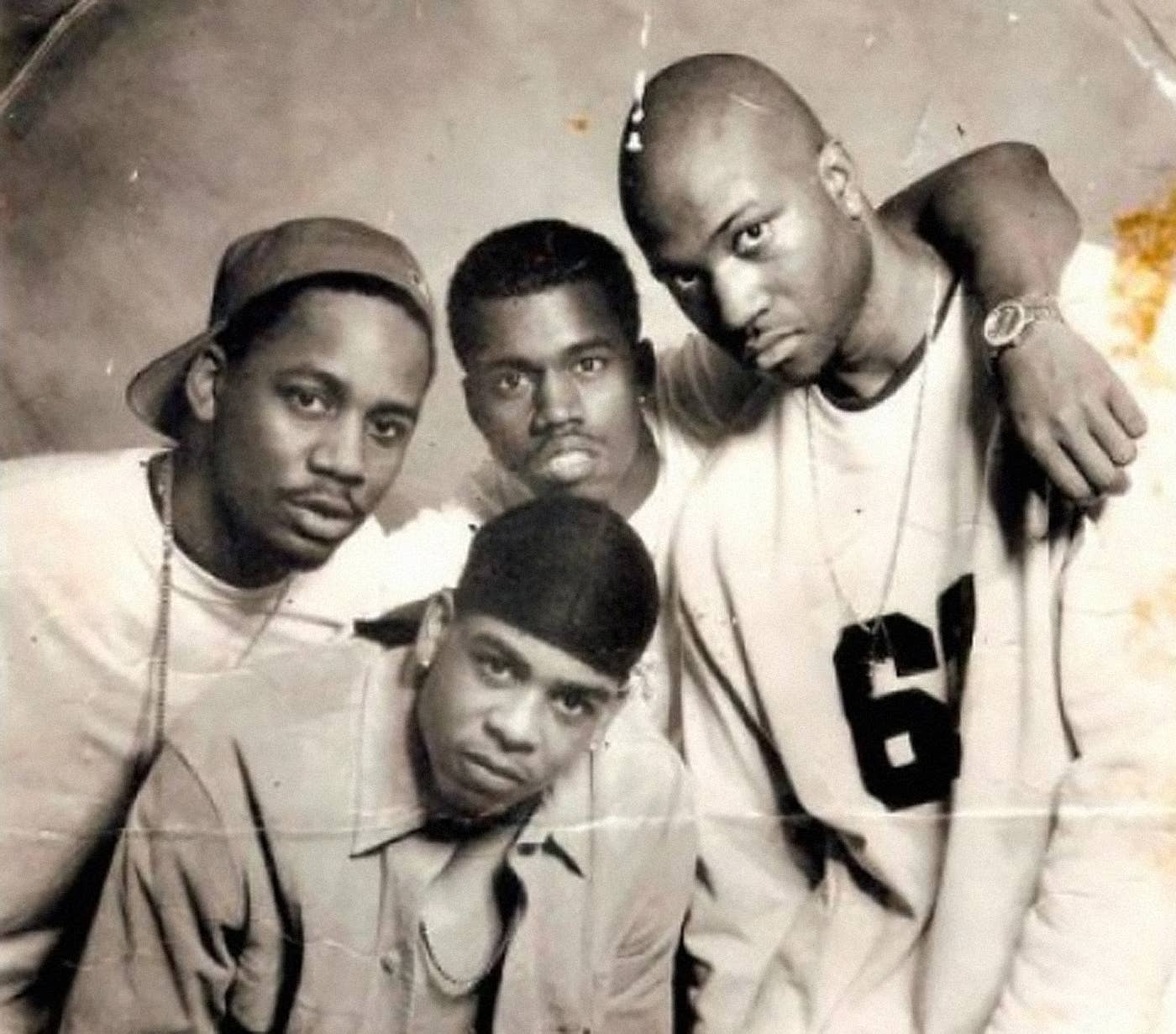

The Go Getters were a Chicago rap group in the mid-to-late ’90s, consisting of a young Kanye West alongside GLC, Timmy G, and Arrowstar. They were orbited by an extended crew of characters familiar to any Kanye fan, from collaborators like Really Doe, Malik Yusef, and Rhymefest, to the group’s managers: cousins Don C and John Monopoly.

The beginnings of the group can be traced back to the day Kanye met Monopoly in 1990, when they were each in their early teens. After being introduced by a mutual friend, the pair admired each other’s beatmaking skills and formed a short-lived production company. “I quit making beats nine months after meeting Kanye West because he was so good and it was like, why am I even doing this?” Monopoly recalls with a laugh.

Despite being cousins, Don C and John Monopoly wouldn’t meet until 1995. “I come from a kind of complicated family,” Monopoly explains. But they quickly became inseparable. At the time of the Go Getters’ formation, Don C and Monopoly had formed a company called Hustle for their music ventures. The cousins wanted to work with their friend Kanye around the same time that Don C’s short-lived rap career as part of a group called Major League ended. (“I'll pay $1,000 to whoever can find the Don C verse” on a song called “Hater Proof,” Monopoly challenges).

“When I got introduced to Kanye's room, it was crates of records everywhere. He had more of a vision and he was more focused than any of us, even as a kid.” - REALLY DOE

Kanye also wanted to work with Don C and Monopoly, but there was a problem. “‘Ye was signed to a production company as a solo artist, and he was frustrated that he couldn't rock with our company Hustle,” Monopoly explains. “So we created the Go Getters kind of as a go-around. It was twofold. One, this was his family. This is who he wanted to be with and who he wanted to come out with initially. And two, we couldn't put him out as a solo artist because of his situation. But that's why it was always ‘Go Getters featuring Kanye West.’ The Go Getters was always about pushing the Kanye initiative. At the time, the only way for us to get any music out was via the Go Getters.”

Kanye and company didn’t have to look far to find other members. Prior to the group’s formation in 1996, GLC was part of a duo with a friend named Andre, who everyone called Birdman (“He kind of looked like a bird,” GLC helpfully explains). Andre, a rapper and producer named Arrowstar, and Kanye all knew each other from grammar school.

GLC recalls Kanye reaching out with a very particular request. “Kanye was like, ‘You need to go solo,’” he says. “So I listened to him. Kanye was doing his solo thing, and then we decided we should come together and do the group.”

GLC knew just who to get to fill out the lineup of the group, which was known as the Chicago Outfit at the time. “I snatched up my little homie from down the street at the time by the name of Timmy G,” he recalls. “I snatched up Arrowstar, because he was cold as shit. He was a motherfuckin’ rap scientist. Arrowstar was the dude that Kanye credits with teaching him how to rap. Really Doe was a guy who lived around the corner from me. He had the potential to rap, but at that time he was in the early stages of really trying to get it together. Go Getters was a crew, and Doe was definitely part of the crew.”

The group frequently worked out of Donda West’s home. “We came from the South Side and we was a little less privileged than Kanye growing up,” Doe remembers. “We kinda grew up in the hood. Mrs. West gave us an outlet to create music in her home in the suburbs.”

It was that same house, Doe recalls, that gave him a clue just how focused his new groupmate was. “In my bedroom, I had the typical posters of Ferraris and girls in bikinis on the wall,” he says. “When I got introduced to Kanye’s room, it was crates of records everywhere. He had more of a vision and he was more focused than any of us, even as a kid.”

After Donda’s house, the group moved to their home away from home, Craig Bauer’s Hinge Studios. But first, they needed a new name since another group had been using Chicago Outfit first. John Monopoly was the one who came up with the name that stuck. “I have an uncle named Roc, [real name] Vernardo Parker,” he explains. “Everybody knows him in the city. He had a restaurant called Paje, a very popular soul food restaurant. He used to say, when a guy was a real hustler or a moneymaker, that he was a ‘real go getter.’ And when he said it one time, I was sitting right around him and I’m like, ‘Yo, that’s a dope name. We’re gonna call the group the Go Getters.’”

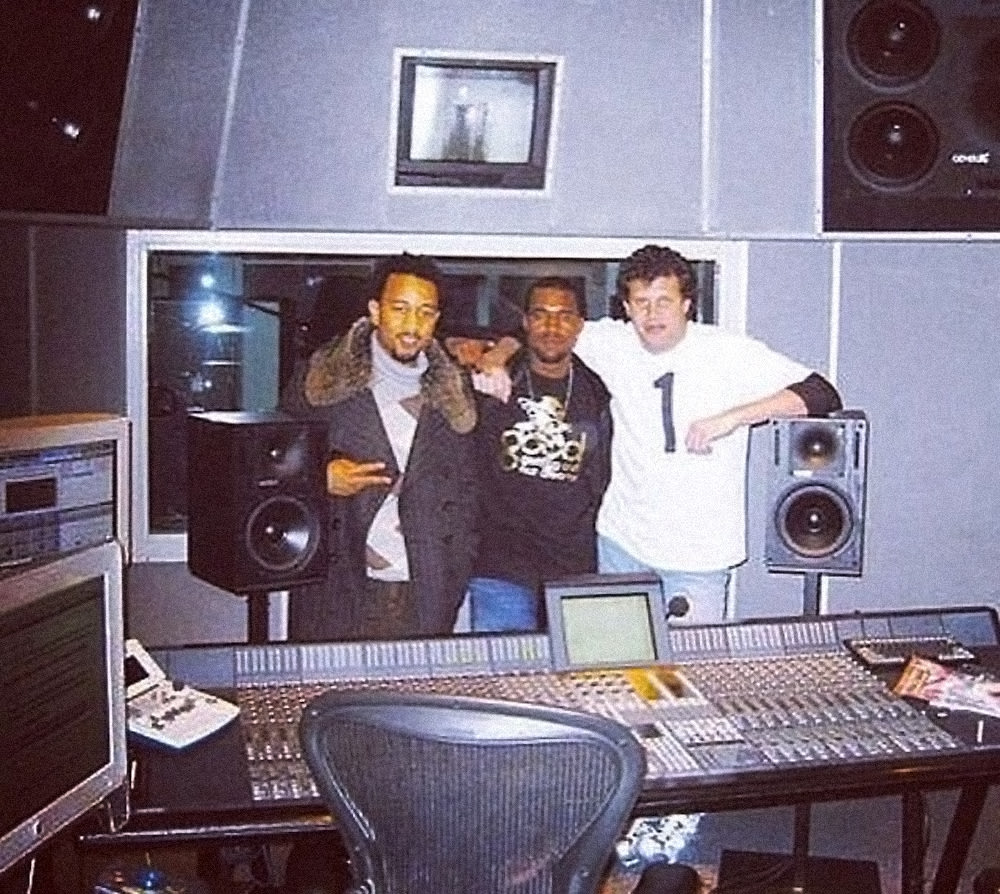

Craig Bauer opened Hinge Studios in early 1993, and a few years later, a young John Monopoly and Don C approached him with a proposal. Bauer, who moved his setup to Los Angeles in 2013, remembers it well. “They called me up one day,” he says of John and Don. “They both came down to the studio; Kanye wasn't there at the time. They walk in the door and we sat down and it was: How can we work something out? How can we get a break on studio time?”

Don C was years away from becoming the influential fashion designer he later turned into, but that doesn’t mean he wasn’t fly even in the ‘90s. “Don C was one of the coldest, freshest-dressing motherfuckers in the history of the city,” GLC says wistfully. “He had throwback jerseys before everybody had them. He was selling Nikes and shit back then off eBay. Way before Don was on the road managing Kanye or anything, he was already selling clothes. He was so smart. This dude was like 19 years old, in the newspaper for trading on the stock market floor and shit.”

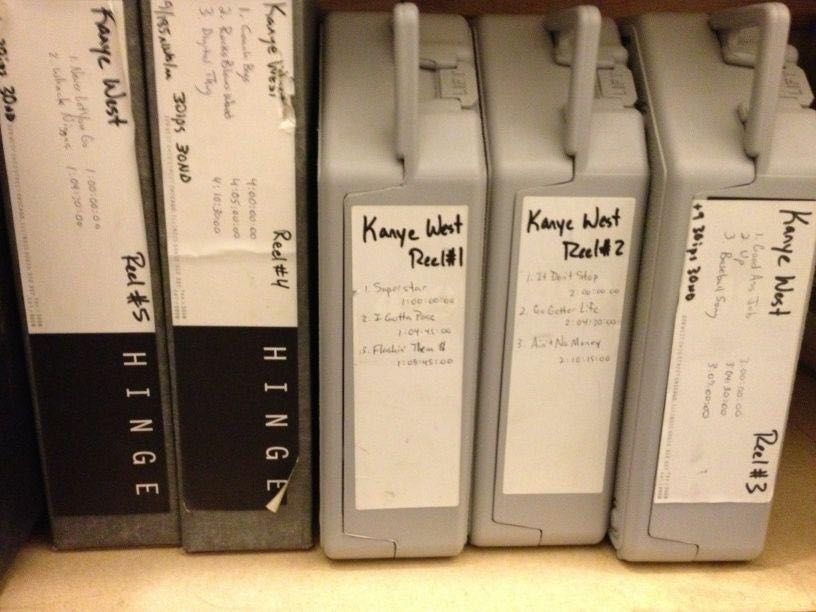

So Don and John managed to talk their way into Hinge, and the Go Getters started working there extensively. “They recorded tons and tons of stuff,” Bauer remembers. The group got along with Bauer, who was only about a decade older than the guys. “We built a strong relationship with Craig,” Really Doe says. “Craig was always there, he was always understanding, he always believed.” Monopoly agrees: “Craig was always a supporter. I looked at Craig more like family. He was always down for us.”

Bauer quickly took notice of the group’s dynamics. “It became clear that [Kanye] was sort of the forefront of the creative process of the group,” he remembers.

’Ye programed beats on his MPC, and then his groupmates would record vocals. Once the songs were finished, the goal was to get them on the radio. Luckily, DJ Pharris was there to help. The radio DJ met Kanye in 1996 through ’Ye’s then-manager Phillip Edwards. And Kanye’s main interest in Pharris? His mom’s record collection.

“KANYE WOULD not leave the house to the point where he grew braids at the keyboard. The guy just didn't stop. He knew he was destined for greatness.” - REALLY DOE

“I was staying in my mom's basement, in a place that they called London Towne Homes,” Pharris says. “Kanye used to come to my mom's all the time. I had so many records that he'd come and just borrow stacks of records to sample. He would leave out of the house with stacks of records taller than him.”

As many remember it, Pharris was the first person to play a Kanye West production on the radio. He worked at WGCI, where he played the group’s song “Uh Oh” (sometimes titled “Oh Oh Oh”). “GCI was the only credible station at the time,” Pharris brags. And the group members were ecstatic when the track got airplay. “I remember when ‘Uh Oh’ hit the radio,” Really Doe says. “It was just ridiculous. We thought we was on. We felt like nothing else mattered.”

Getting the song on the radio was not easy, though. Monopoly led a picket line outside the station to force it to play the track (you can see a sign from the effort below).

“I had a street team picket outside of GCI with these signs saying, ‘Play the Go Getters,’” Monopoly recalls, explaining that the song was already so hot that DJs would share snippets of it going into commercial breaks, but refused to play the entire track until he forced their hand.

GLC remembers, though, that Pharris played a track even before “Uh Oh” broke: a song called “Street Love” that the group recorded when they were still called the Chicago Outfit. “Every party you went to, when we walked in and we was on the radio… Man, that shit felt like we was walking on sunshine.”

“Street Love” was not an anomalous title. The group’s lyrics had a little more of a tough-talking edge than fans of Kanye’s solo work might expect. GLC explains that was because of where (most of) the group members came from. “Our music was an escape because of the shit that we was dealing with in the hood,” he says. “Like, Kanye's mama lived in the suburbs, so she used to allow us to leave what the news would call a war zone—the Auburn Gresham neighborhood in Chicago—and come out to her nice crib in the suburbs and record songs and do something to escape the environment that was being plagued with violence and genocide. So those songs were a reflection of that, on top of the fact that we were making light out of the situation.”

So, with songs on the radio, popular T-shirts (in maroon and gold, blue and gold, and blue and orange variations, in “Glue” font), ambitious managers, and Kanye West beats, why didn’t the Go Getters take off?

They almost did. Monopoly recalls that in 1999, the group was on the verge of a big deal with Elektra Records. He says there was a big meeting with then-label executive Merlin Bobb, but “somebody fumbled the ball. I’m not going to say who, but it wasn’t Kanye.”

“Kanye's mama lived in the suburbs, so she used to allow us to leave what the news would call a war zone—the Auburn Gresham neighborhood in Chicago—and come out to her nice crib in the suburbs and record songs and do something to escape the environment that was being plagued with violence and genocide.” - GLC

In fact, Monopoly remembers flying back and forth to New York City a lot towards the end of their time together, in hopes of gaining industry traction. He recalls a near-signing with Richard “Younglord” Frierson’s label around the same time Elektra was interested. And it was all possible thanks to a special friend. “When I was putting out the Go Getters, I was dating a young lady who gave me all of her flight benefits because she worked for American Airlines,” he says. “She gave me probably 20 flight passes, and I used those flight passes to go to New York and shop Kanye and the Go Getters, shop No I.D. [who Monopoly was managing, and who produced “Uh Oh”’s b-side “Let My Niggas In”], and build my company. None of that would have been possible if it wasn't for her giving me those flight passes.”

While the Go Getters may not have had landed a big record deal from all those flights, their central figure was taking off anyway. Around that time, Kanye hooked up with producer Deric “D-Dot” Angelettie, a former member of Puffy’s storied Hitmen production team. The pairing worked because, as Pharris recalls emphatically, a young ’Ye was “a huge fan of Puffy.” As Kanye’s beatmaking career took off, he moved from Chicago to New Jersey, and the Go Getters as a group slowly faded.

“It was never really a falling out or anything crazy like that,” Really Doe says. “We always felt like there was never an end to it, because we were family.”

GLC remembers that ’Ye was determined that if he made it out east, he’d come back and bring along his crew. “He was like, ‘Man, I’m gonna focus on these beats. I'm going to move out here to New York. If I get shit popping, we’re gonna do what we said we was gonna do.”

Kanye’s former groupmate kept sending him material after the move. “Every week, I'm sending Kanye CDs,” GLC says. “I was a recording motherfucker, man. I might send seven songs a week. Kanye would listen to them, and he would find shit that he liked. He would take parts of the shit and build off of it and create new songs. So he’ll take like the foundations that I would send him and he would take the shit to another level.” GLC cites Kanye’s verse on “Champions” as an example of using a flow that he originated: “I sent him the pattern that he used on ‘Champions.’ Not the lyrics, but the flow, the delivery.”

Once Kanye moved to New York, Roc-A-Fella and solo stardom followed shortly thereafter. When he found success, the former Go Getters were not surprised. They had seen his dedication firsthand. Really Doe says he “used to go to sleep to ’Ye making beats and waking up to him fucking making beats.” He adds, “I watched him one summer just not do anything [but make beats]. I mean, not leave the house to the point where he grew braids at the keyboard. The guy just didn't stop. He knew he was destined for greatness.”

When the members of Go Getters look back on their time together, they have nothing but fond memories. “We was ahead of our time a little,” GLC says. And what sticks with Really Doe is how much they all loved the music. Recalling a moment involving Kanye and his future “big brother,” Doe says, “I can remember when we was creating the Go Getters album and Jay had dropped ‘Ain't No Nigga’ with Foxy Brown. I remember me and ’Ye riding around for maybe two hours with that track on repeat, just listening to the lyrics.

“We were fans of the art,” he adds. “That’s what created focus: loving hip-hop and loving music.”

ComplexCon is coming to Chicago on July 20-21, 2019. Experience the festival and exhibition at McCormick Place, featuring performances, panels, and more. For ticket info, click here.