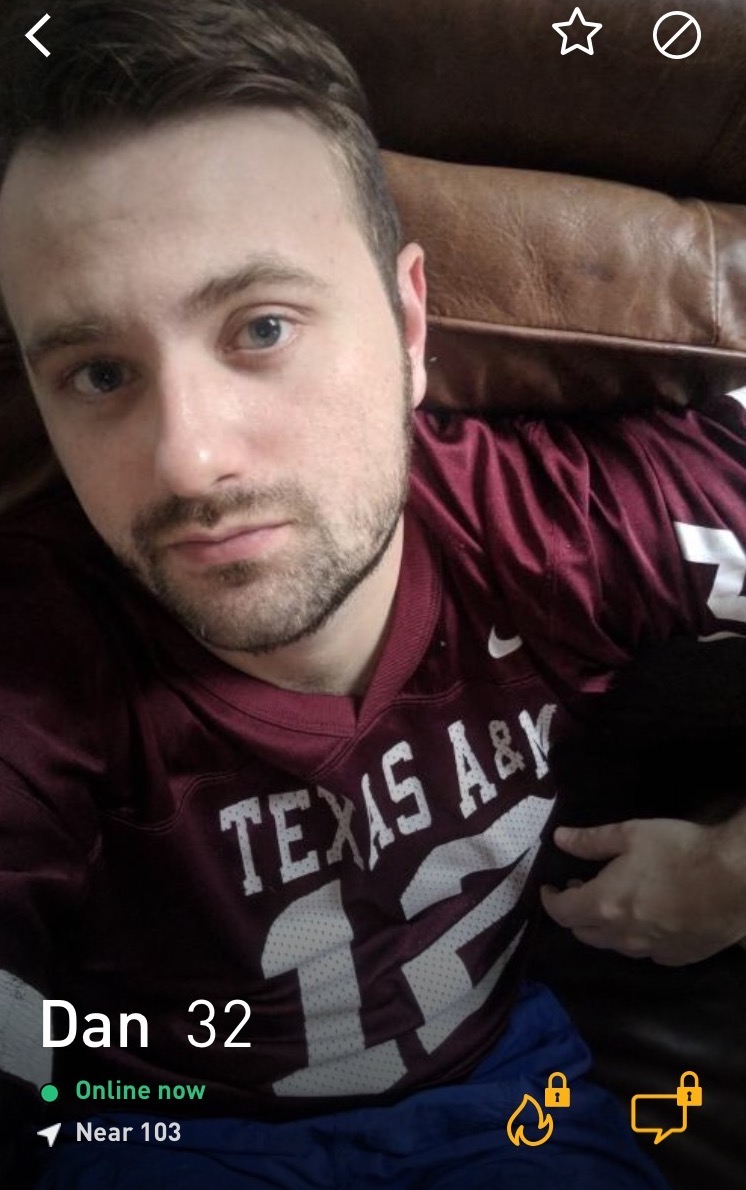

The man in the Grindr photo stared into the camera, his expression sullen yet enigmatic. In his bio he’d written “Be Kind.” But it was his Texas A&M football jersey that caught the attention of 26-year-old Casey Holliday as he scrolled through the dating app one evening last May. Holliday, who lives in Manhattan, attended rival Ole Miss, and the man reminded him of guys from college. His name was Daniel Spence.

That night in Holliday’s Lower East Side apartment, Spence, 32, strode in with a confident look that impressed Holliday, who lived with two roommates in a buzzer-less 5th floor walkup. Spence wore a Ralph Lauren T-shirt and matching sweatpants, the sort of shabby-but-not-too-shabby weekend look of a Wall Streeter who only shopped at Nordstrom. “He was southern-frat handsome,” Holliday told me. With a slight paunch, patchy beard and parted bangs, Spence resembled “the kind of guys with dad bods, thinning hair and destined to make hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Subscribe to Observer’s Daily Newsletter

Speaking with a soft, lilting drawl, Spence told Holliday he was the nephew of Austin advertising icon Roy Spence, whose firm coined the slogan “Don’t mess with Texas.” After graduating from A&M, Spence later said, he’d built his mother’s media company, which he inherited in high school, into a multi-million dollar operation before selling it. Holliday, a lanky 6-footer with short dark hair, enjoyed the conversation, but some of Spence’s comments struck him as odd, like when he claimed his godfather founded Popeyes. Holliday second-guessed him at first, but then reasoned, Somebody has to be that guy’s godson.

Glancing at a copy of Brooklyn Magazine on Holliday’s TV stand, Spence mused, “It’s such a valuable brand name. I’ve always wanted to own a magazine.” Holliday gave a slight eye roll before explaining that he worked for the magazine’s owner, Northside Media Group.

The dominant media icon of Brooklyn’s trendy Williamsburg neighborhood, Northside began in 2003 when trailblazers were settling in, rising to parallel acclaim as Williamsburg established its reign of Brooklyn hipsterdom. In addition to Brooklyn Magazine, Northside ran an annual music and tech festival, along with a food summit, both to wild success.

But behind the scenes, Northside was in trouble. In 2015, with a peak staff of around 25, the media company was sold to a Los Angeles conglomerate, which apparently mismanaged it. Two years later, the founders bought it back, accumulating heavy debt. By last year, its staff had dwindled to nine, and freelancers were demanding back-pay. After multiple relocations and the shutdown of Brooklyn Magazine’s print edition, there were rumblings of closure.

Holliday didn’t mention any of this to Spence in his apartment but alluded to it afterward. For two weeks, as Holliday pondered a relationship, Spence peppered him with more Northside questions—its valuation, price tag, investor interest. Holliday invited him to the upcoming music festival, where Spence could meet some people.

If Spence’s introduction to the media company was accidental, his interest in profiting from it fit a pernicious, eight-year pattern that stretched across several states. Spence was a scam artist, having bilked people out of hundreds of thousands of dollars, they allege, through Ponzi-like schemes, shell companies and other outright lies.

But he was no run-of-the-mill conman. In an audaciously twisted fashion, the majority of his victims were the people who trusted him most: childhood friends, family members and men he met on dating apps.

***

As the sun set over a sweeping Manhattan skyline, a large crowd frolicked on a boutique hotel rooftop in Williamsburg. The opening-night party of the five-day Northside Festival last June was jammed with premium sponsors, clients and influencers. Sifting through the crowd was Spence, who worked it with charm. When a chill blew through, he fetched several jackets from his apartment around the corner, which he rented for $5,400 a month.

Flanking Spence was a banker flown in from Cleveland, and a personal assistant, clad in a velvet suit and carrying Spence’s shopping bag. Spence dropped hints that he was in the market for a media company, wowing staffers with his industry knowledge and personal interest in them. When a Northsider named Emily confided earlier in the day that she was considering leaving the struggling business, Spence replied, “What would it take to keep you?” Under his leadership, Spence told Emily, everyone would receive raises, and she’d get an assistant. “I’m like, ‘You know exactly what we need to hear,'” she told me.

Days later, Spence was face-to-face with Northside co-founder Danny Stedman, a well-regarded influencer credited with creating one of Brooklyn’s most revered cultural brands. Stedman was seeking deep-pocketed investors interested in Northside’s cool cachet to save Northside, but two recent candidates had fallen through, and by the time Spence came around, Emily recalled, “Danny’s desperation was evident.”

Spence offered to inject millions into Northside in return for becoming CEO. Near-daily conversations continued for two months as the men shared their visions for the next era of hip-kid dominance. Spence delivered the same backstory he’d given Holliday—that he was the protege of “Uncle Roy” and that he sold his family media company for $60 million. At one point, according to Stedman, Spence thumbed a phone app to display a bank account showing $150 million, and later provided SEC documents confirming his wealth.

As the men warmed to each other, Spence opened up about the hardships of growing up gay in a right-wing Christian family. Sometimes he smoked weed out of a vape pen, presenting himself as creative, yet humble. “He had no pretense,” Stedman told me. Their bond culminated over an intimate dinner with Stedman’s wife.

Meanwhile, Holliday and Spence continued their quasi-romantic relationship. The first night Holliday visited his apartment, Spence insisted they initially talk in the first-floor game room, furnished with a foosball and an air hockey table, a flat screen TV and a dartboard. Rich people shit, Holliday thought.

As they sank into the sofa, Spence made another odd comment. “I’ve been in four major relationships, and after each one ended, I bought my ex a large piece of property.”

“Why are you giving me an end game, bro?” an unsettled Holliday joked. The response was laced with Holliday’s trademark sarcasm that, according to friends, belied a big heart and sensitivity about how others perceived him. Despite his outward self-assurance, one friend said, “underneath, he can be somewhat shy and reserved, especially concerning the most important aspects of his life.”

Spence pressed the subject, telling Holliday that his most recent ex, an aspiring actor named Max (his middle name) lived in a nearby brownstone he’d purchased; but he had put it back on the market because Max was planning a move to LA, Spence said, so in the meantime, Max was crashing with him.

Upstairs, after an awkward introduction to Max, Holliday strolled through the apartment, which featured industrial-rustic tones, reclaimed wood-beamed paneling, a dining room, dual-nozzle shower heads and a walk-in closet full of shoes and dry-cleaning bundles.

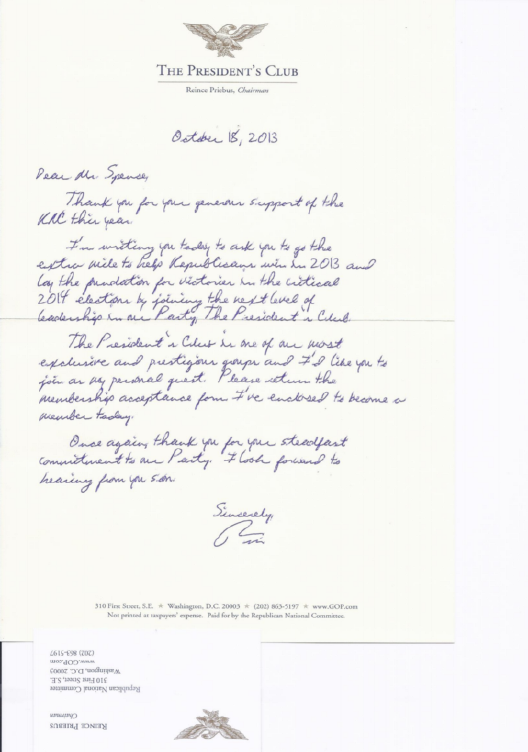

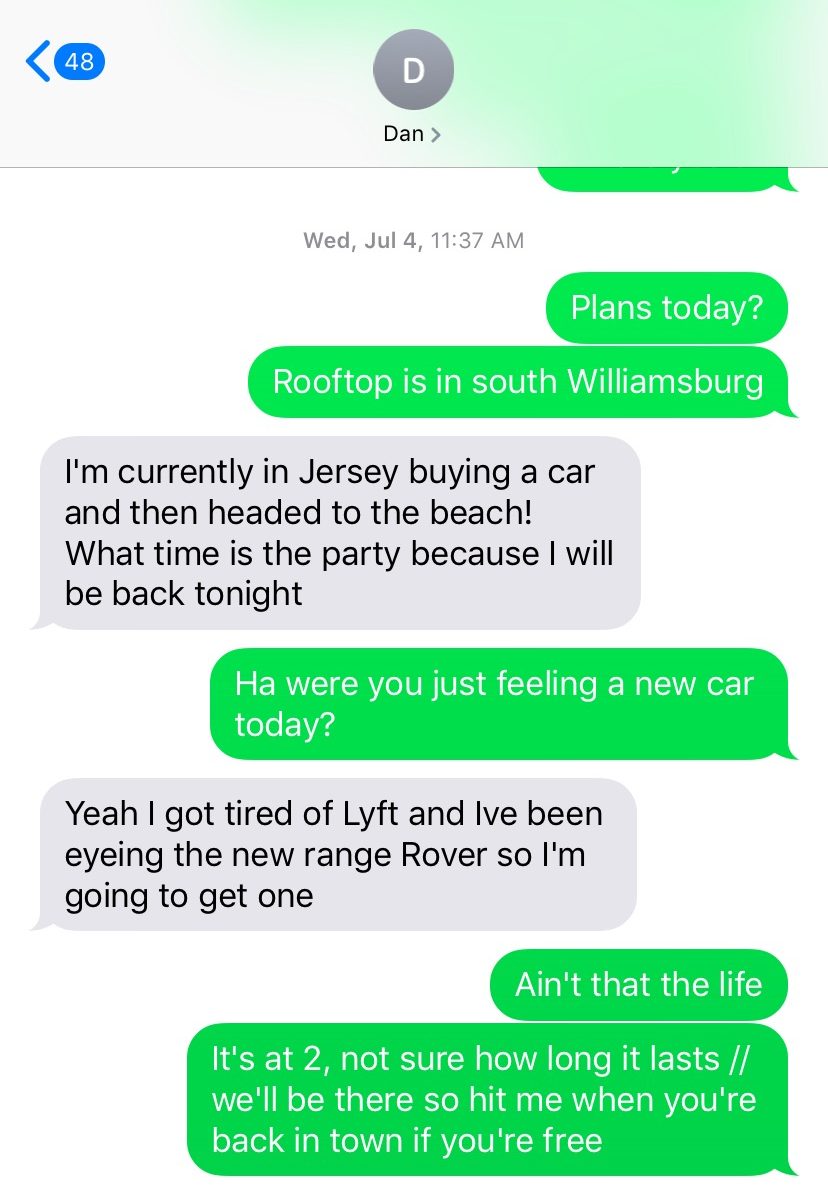

Evidence of Spence’s opulent tastes grew that month. There was the $40 burger joint with personalized names imprinted on the buns; Spence’s suggestion that Holliday accompany him to a Barneys tuxedo fitting; a screenshot of a 2013 letter scribed by then-RNC chairman Reince Priebus thanking Spence for his contributions; Spence’s odd claim that his identity had been sold on the dark web for $99,000 (“I’m only worth ninety-nine grand?” he joked); and a trip to Bergdorf Goodman’s restaurant, where Spence pre-ordered their meal and the purported head chef greeted them. Spence bragged about his newly purchased apartment in Crown Heights—or was it the Brooklyn waterfront?—big enough to park his yacht, and a Hamptons home, available to Holliday and his friends any time. In one text, Spence wrote, “I got tired of Lyft and I’ve been eyeing the new Range Rover so I’m going to get one.”

To Holliday, the head-spinning experience mimicked the Gossip Girl episodes he cherished growing up outside of Memphis, where he lived in a modest home his father built from scratch. But this was New York, where Spence’s behavior was normal… right? For countless millennials raised on Sex and the City, Dan Spence was a reality—the promise of a new and glamorous life awaiting them on the other side of the Hudson River. Whatever doubts Holliday had about Spence’s credibility—and he had a few—they were overshadowed by an uncertainty that a high-roller like Spence could have feelings for a guy like him.

But strange things continued happening. When Holliday and his roommates googled Spence’s name, there was no internet presence, other than an ugly business website. His Lyft account was registered to “Mary,” who Spence claimed was his head of HR. The open invitation to the Hamptons never materialized, and Max never moved out. Eventually, Holliday learned his own cell number wasn’t even saved in Spence’s phone. “The sketchiness started to be annoyingly sketchy,” he said. Most frustrating, Spence always had an excuse for being unable to hang out—too many meetings with bankers, politicos and editors, he lamented

The only time Spence seemed interested in an exclusive relationship was when the conversation turned to Northside. While he promised Holliday a large finder’s fee and a new title, Holliday told his boss that if Spence came onboard, he’d resign. As the weeks went on, Holliday felt his relationship with his one-time Grindr date drifting into more of a friendship.

Negotiations with Stedman made headway, and by mid-July, Northside faced a make-or-break moment. News reports had come out detailing Northside’s financial woes. Stedman was put on the defensive, accused of delinquency in freelancer wages dating to Northside’s reacquisition. In a message to a freelancer, Stedman reportedly wrote, “All intentions and hopes (not ready to make a promise) is that this will be paid in full in 45-60 days.”

By the end of the month, Spence’s law firm indicated that final paperwork would arrive within the week. Spence’s offer “was more than enough to reimburse everyone owed by the business and put us on a healthy pathway forward,” Stedman said. With international law firm Perkins Coie representing Northside, a signing party was scheduled, with plans to move the company to a hip new office space already under renovation.

“Dan was going to save the whole company,” one staffer recalled.

Days before the signing, Stedman was scheduled to meet Spence at a Northside outdoor film screening, but the would-be CEO didn’t show. A few days later, a flustered Stedman tracked down Holliday.

“Have you heard from Dan?”

***

Two years earlier, a Nashville resident I’ll call Brian received a Grindr message from Spence. At the time, Spence lived in Austin but was in Nashville, he told Brian, to represent his company in court. After a brief online chat, the two met for dinner.

Brian, 24, quickly took to Spence, who seemed personable and worldly. Sporting a crisp polo, Spence told Brian he owned a Southern-inspired clothier, was the nephew of Austin’s Roy Spence and ran the Houston-based ad agency KLS Media, which focused on mass tort law and claimed BP as a client. After dinner, Spence asked for a tour of Belle Meade, an old-money neighborhood dotted with mansions. “I need to get in on that,” Spence observed.

The evening had platonic vibes, but was still a thrill for Brian, who saw Spence as a potential mentor. “It seemed we were meant to be good friends,” he told me. One of Spence’s comments stood out: “I hate that the first thing you see when you google me is how much money I make.”

The next day, Brian searched Spence’s name and found a Bloomberg Executive profile suggesting annual earnings just shy of $4 million, with his mother earning $700,000 as KLS’s chief creative officer. A KLS website was under construction, but Brian’s search uncovered favorable Glassdoor reviews and press releases.

Over the next year, the two men texted or talked nearly every day. Brian had yet to come out to his family, and Spence coached him on how to approach it. In March of 2017, Spence pitched Brian on a deal involving a trust fund for asbestos victims, explaining that KLS was producing television commercials on behalf of law firms looking to recruit clients. KLS would take a cut of any settlement money. Brian says he invested $10,000.

Spence said he’d submit paperwork for signature cards allowing Brian to track the fund’s growth, requiring Brian to email his social security number and other personal information to a man named Andrew Lehman—KLS’s CFO, said Spence.

A few weeks later, Brian got a call from Goldman Sachs inquiring about a personal line of credit he never applied for. Spence told Brian not to worry; all the investors had been hacked, but the funds were secure—Andrew Lehman was handling everything. Brian received a formal letter, typed on Spence Family Investments stationary and copying several other apparent investors, dispelling any fears about the hack.

Beyond that hiccup, Brian, who was burning out at his job, was stoked about the new investment, as if his introduction to Spence in Nashville was fated. When Brian and friends visited Austin, Spence picked up the $800 dinner tab. Later, he told Brian that he’d sold KLS and was flush with cash, proposing they open a media buying house together. Soon, Spence was crowing about their first client—a Dallas car mogul looking to spend $20 million. Brian scouted out Nashville luxury apartments to convert into offices, dined with potential bankers and made plans to quit his job.

While this was going on, Brian noticed his credit score had dropped 100 points. He searched his financials and recalls that $42,000 in charges had been linked to an unfamiliar Navy Federal Credit Union account. Again, Spence claimed the glitch was related to the earlier hack and that Andrew Lehman would fix it.

Uneasy with that answer, Brian nevertheless planned to celebrate the new business partnership with Spence’s East Hampton crowd, and Brian hopped a flight to New York City. Upon landing, he received a voicemail from Spence saying that something had prevented him from traveling, but that he had booked a five-star hotel room for Brian. Even so, Brian looked forward to the Hamptons party later that week. But when the day arrived, Spence still wasn’t in town.

“It was the first time I saw the writing on the wall,” said Brian.

***

Spence grew up in Beaumont, Texas, and when he was 11, tragedy struck. As he and one of his three sisters crossed the street one evening, a truck hit the girl, killing her in front of his eyes. Spence told friends the accident never affected him, but according to one person close to his family, the experience left the boy deeply shaken.

His single mother, Mary Derby, toiled in the advertising world, teaching Sunday school on the side. Spence assumed a head-of-the-household role, cosigning onto his mother’s financial accounts and allowing her to lean on him emotionally. A svelte woman with a Southern sweet-but-reserved demeanor, Derby eventually launched her own ad agency out of her house, dispatching Spence to drop off materials to media stations and scout out billboards. She named the business KLS Media—the initials of Spence’s deceased sister.

Classmates from his small Christian high school recall Spence as charismatic and intelligent—a quick-on-his-feet problem-solver who schmoozed easily with adults. “He could talk his way out of anything,” one recalled. “He walked into the principal’s office like he was 35.”

But Spence never applied himself academically—he plagiarized at least one paper, according to a friend—and was more interested in getting rich quick. “That was Daniel’s dream, to become a millionaire overnight,” said a classmate. During a junior year trip to New York, he admired the city’s gleaming skyscrapers and announced his desire to own one. “Spence Tower,” he imagined.

After high school and a year of community college, Spence enrolled in Texas A&M. He joined a Christian fraternity, attended campus praise and worship gatherings and led a prayer group out of his apartment.

But during that time, he was also becoming a pathological liar, maintaining the façade of a full-time student, though he’d clearly stopped going to classes. “Little lies turned into bigger lies,” recalled a roommate, who said Spence blew tuition money on other things. (Records indicate Spence only attended A&M from January to May of 2009.) In 2010, he left town, skipping out on two months of rent, according to a civil lawsuit, and bilking an optometrist, leading to a second lawsuit and a complaint from a bondsman trying to track him down. By then, he was in Fort Worth, looking to make money.

Tyler Wagner had met Spence through his cousin, a member of Spence’s fraternity. “He presented himself as this good faithful Christian trying to do his best in the world,” Wagner told me. Spence suggested they start a business together; Spence would sell ads, and Wagner, a recent college graduate with little money, would design them. Spence claimed he had plenty of capital, thanks to his Uncle Roy’s mentorship, acquisition of KLS and the asbestos trust fund. After agreeing to become roommates, Spence insisted they move into an expensive Fort Worth apartment; Derby later joined them.

To kick off their venture, Spence would apply for company credit cards; Wagner provided his social security number. During the ensuing months, Wagner noticed that Spence had a habit of taking financial mail addressed to him. Wagner entered Spence’s room and saw stacks of paperwork showing that Wagner was thousands of dollars in debt, he says. When he confronted Spence, his roommate locked himself in his bedroom, complaining of vomiting blood.

Later that day, Spence and his mother vanished. Wagner visited the hospital, but there was no record of Spence. Spence left a message saying he’d checked into a different hospital in Houston and had received a cancer diagnosis, Wagner recalled. He never saw Spence again in Fort Worth.

Ultimately, says Wagner, Spence ran up $20,000 under his name and stole one of his personal credit cards. Wagner let the debt go to a collection agency. It grew to $25,000 and ruined seven years of his credit.

***

After reemerging in Louisiana, Spence and Derby were invited to stay at a friend’s house. At first, “they were super sweet,” recalled the friend, but soon began holing up in a bedroom in secrecy. After six months, they disappeared with the friend’s $6,000 diamond ring. “It was like [the film] Catch Me If You Can.”

The pair bounced around Texas, moving into upscale homes and taking luxurious trips together, including a month in the Hamptons. Was KLS doing that good? family wondered. A hint of truth came when a relative, who asked that only his first name, David, be used, received a call from his company saying he owed $17,000 in credit card charges. David logged onto his account and eventually traced several transfers to KLS Media and realized Spence had gotten ahold of his company card. Spence was also taking out loans in a sister’s name, too, according to one person close to the family.

David believes Derby might have been the mastermind. “They definitely worked as a team, as far as I’m concerned,” he said. “Who moves around with their son like that?” (Derby did not return phone calls.)

Meanwhile, Spence kept up with high school friends, claiming he was a New York real estate lawyer. Strange though it was, Spence sometimes did prove he had money, like the time he donated $40,000 for a university soccer team’s mission trip to Africa, as a favor to a friend. After that, three former classmates invested five-figure amounts into his funds, according to a high school friend. (None of the three classmates could be reached independently, but in a message, the father of one said of Spence, “He’s a modern day master scam artist. Period! I’m surprised he’s not dead!”)

Later, Spence offered to line up a friend’s husband with a BP internship through his consultancy contacts. A congratulatory email appeared in the husband’s inbox, and a contract arrived in the mail. Months later, the husband called BP’s HR department and learned there was no record of him.

“We were like, ‘Oh my God, this is a lie!'” Spence’s friend recalled.

By 2014, Spence and Derby were living in a nice house on a cul-de-sac outside of Nashville with three cars in the driveway, when he offered his landscaper, Justin Huffman, a chance to invest in his asbestos fund. “Everything seemed legit,” Huffman told me. He fronted $180,000, and his friends contributed another $155,000.

Months went by without updates. To quell any nerves, Spence invited Huffman to what he claimed was his Hamptons home. They arrived at a house party via helicopter and watched horses get auctioned off, Huffman said, and later travelled by limo to a Trump complex, where Spence claimed to keep an apartment. “The doorman was like, ‘Good evening, Mr. Spence!'” Huffman recalled.

Around that time, Spence applied for a multi-million dollar insurance plan to protect his estate, but was exposed when two AIG representatives flew to Nashville from New York to declare Spence was a fraud, Huffman said. (A police report purports that Spence signed AIG paperwork using a sister’s name; the sister told police that Spence had forged her signature and scammed Huffman “out of a quarter of a million dollars.”)

When Huffman learned the score, “I was mad as hell,” he said. He drove to Spence’s house, where a moving truck was parked outside. Huffman tailed the truck to another home, where a security guard Spence had contracted was waiting. (Spence confirmed the security detail in his own police report.)

Three weeks later, Huffman saw an 18-wheeler parked outside the new home. In the middle of the night, he says, he cut a hole in the bottom of the moving truck and fastened to it a fully charged iPhone to serve as a GPS. The next day, Huffman followed the signal through Arkansas and into Texas, making up 120 miles of highway. When he arrived at Spence’s new gated subdivision in Austin, he couldn’t get past a guard shack. He trudged to Spence’s home through a back-entrance park. Spotting Spence and Derby on the porch, “I made some hand gestures”—he declined to go into detail—”and said some other stuff, letting him know I knew where he was.”

Back in Tennessee, one of Huffman’s friends, Matt Bartlett, who’d invested $100,000 with Spence, organized continued stakeouts by phone through contacts in Austin. “I sent one of my boys who was a bounty hunter-slash-lunatic to watch,” he told me. (He declined to provide the bounty hunter’s contact information.)

Huffman and one of his friends filed charges, leading to an indictment for two felony thefts. “He met his match in Tennessee,” Huffman said. “I’m not normally that crazy. But someone steals that much money, it can cause you to do some strange things.”

Spence mailed Huffman and his friends reimbursement checks, but Huffman told police they bounced. In 2015, Spence was arrested (it’s unclear how) and jailed. A tearful Derby called one of Spence’s high school friends to lobby, unsuccessfully, for bail money. After three months, Spence pleaded guilty. A Tennessee judge gave him a six-year sentence but suspended it, placing him on probation. Against court orders, he returned to Austin.

Three months later, during a 2016 visit to Nashville, for what may have been a probation hearing, Spence sent his original Grindr message to Brian.

***

Though Brian had grown wary of Spence after the Hamptons debacle, business developments continued. Spence blamed the Hamptons no-show on a crisis surrounding their first client, the Dallas car mogul. In a three-way text with Spence and Brian, the purported car mogul—his photo was even attached to his phone profile—said, “Hey guys good work this week. We appreciate all you’ve done for our family.”

“Boy that Daniel is something else man,” the mogul added. “Bulldog.” The conversation veered toward private jets and bonus checks; Spence said they’d soon be celebrating over “sinfully expensive” champagne.

At the time, Spence was living with a boyfriend, Max. A slightly framed Long Island native, he met Spence through the dating site OkCupid shortly after moving to Austin following college. At the time, “I didn’t have a pot to piss in,” Max told me. Spence was always buying things for them when they’d go out, squired him around in his BMW 5 and pledged to convert to Judaism, endearing himself to Max’s parents. Max’s first adult relationship felt like love.

But Spence had an emotionally manipulative streak, Max went on. If he was serious about becoming an actor, Spence instructed, Max would need to quit his job, engage in twice-a-day workouts with a personal trainer and increase his daily food intake to 4,000 calories.

The efforts seemed to pay off, as Max began receiving official-looking letters from IMG Models, and Disney, which was casting for the film Richie Rich. A $20 million film produced by Annapurna Pictures about Peter Thiel was in the works, and Max would be perfect, Spence exclaimed. “I physically signed a contract,” Max recalled.

Spence told Max he was going to open a business—to be called Oceanview Drive Partners, named for Spence’s purported Hamptons address. Around this time, Max says Spence stole his social security number off work forms.

Max began noticing strange things. After Spence purchased a $1,500 puppy for Max’s birthday, the breeder left an angry voicemail complaining the check had bounced. Spence refused to fly anywhere, even during long trips. He also spent an abnormal amount of time on the phone with his mother.

Meanwhile, in Nashville, after repeated unsuccessful attempts to meet up with the car mogul, Brian again grew suspicious. He noticed that $35,000 had been charged to his new business credit card. Spence told him that Andrew Lehman was on top of everything. “Your diligence is the number one reason I want to go into business with you,” Spence reassured him.

Soon after, Brian recalls getting a call from a Navy Federal Credit Union investigator claiming he owed $42,000. Brian told the investigator that Andrew Lehman was taking care of it. “No one’s taking care of it,” replied the investigator. (I couldn’t track down anyone in Houston named Andrew Lehman; Brian now says he’s almost certainly fake.)

Brian says the investigator forwarded him recordings of his personal conversations with a man claiming to be Brian, asking about cash advances. But the man’s voice belonged to Spence.

“I didn’t want to believe it was him,” Brian said. “No one wants to believe a friend, who I still thought was a millionaire, could do that.”

In total, says Brian, Spence ran up $78,000 under his name, with much of the money funneled to Oceanview Drive Partners—in other words, $78,000 paid directly to Spence. There were also a few Popeyes charges Spence had put on Brian’s card. (Brian provided letters from Navy Federal Credit Union and the credit card company confirming the fraud investigation.)

Brian deleted all mentions of Spence from his LinkedIn account and told his friends to block him on social media. Brian assumes that Spence learned the credit card account had been flagged as fraudulent, and that Brian was onto him. Whatever the case, Spence texted Brian, declaring he was moving to Los Angeles for another venture. “Regardless of what I am advised,” he wrote, “I love you and will do whatever I can to wrap this up amicably.”

Suddenly for Brian, it was no longer about the money. It was personal: “He taught me how to come out to my parents. That’s where it seems perverted.”

There were other bad acts in Spence’s recent history. In 2014, Spence made a $2 million offer to purchase a Nashville home. When the signing date arrived, Spence ghosted. A judge issued an $189,000 judgement for the owner, which went unpaid. “We had verification he had $5 million from a legitimate New York bank,” the owner’s befuddled lawyer told me.

The following year, Spence made an offer for a $3.5 million Austin apartment, but at the signing table, he said the wire transfer had been delayed. Even so, Spence, his broker and then-boyfriend (prior to Max), celebrated that night with a penthouse dinner and a bottle of Cristal. For 10 days, Spence tried to stall the signing with various excuses and, after that, the buyer’s agent never heard from Spence again. “He baffled us all,” the broker, Eric Copper, told me. (In another example fitting Spence’s pattern, Copper said he later received a call from Spence’s then-boyfriend “practically in tears,” accusing Spence of exploiting him financially. The boyfriend declined to comment for this story, citing stress and privacy.)

After Spence violated his probation terms in 2016, Tennessee authorities couldn’t locate him. Meanwhile, Bartlett, Huffman and others had managed to find each other. They created a Facebook group called “The Hunt for Daniel Spence.” They used his mugshot as a profile image.

***

Spence and Max had moved to Williamsburg six months prior, in November of 2017. At first, Spence ferried his boyfriend around to chic gatherings with private bankers—for Max, the New York dream had come alive. Yet something was off. “My family was like, ‘When’s this movie happening?'” he recalled. Eventually, he and Spence began an open relationship—which explains why Max didn’t protest when Casey Holliday visited the apartment. “I felt trapped,” Max said.

Meanwhile, when Spence failed to meet Stedman at the outdoor film screening days before the Northside takeover, Stedman, unsure of where else to turn, cold-called Roy Spence, the Austin ad mogul.

“Dan Spence is not my nephew,” said the voice on the other end of the line. “This isn’t the first time this has happened, and it needs to be stopped.” (Roy Spence declined to comment for this article.)

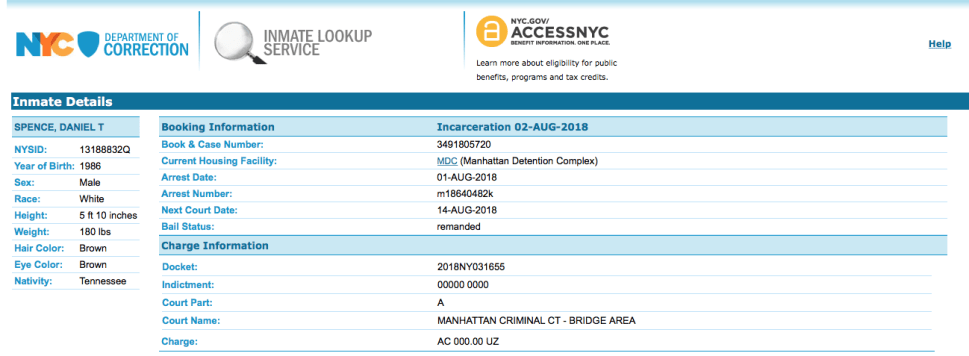

Roy Spence’s wishes, in a sense, had already come true; Dan Spence was in jail. Tennessee authorities had tracked him to Williamsburg. At 6 a.m. on the day he was to meet Stedman at the film screening, police arrested Spence at his apartment as a fugitive of justice. He was extradited to Tennessee and detained. In addition to his probation violation, more charges including theft and embezzlement were levied against him in the cases of Brian and Matt Bartlett.

When Stedman told Holliday about the arrest, Spence’s one-time Grindr date felt a sense of whiplash. On one hand, his uncertainty about Spence’s legitimacy was validated; he was finally free from any insecurity that he wasn’t good enough for a man of such wealth. On the other hand, he was pissed off at all the wasted worry.

Spence left behind more than $50,000 in back rent at his Williamsburg apartment. But recouping those charges will be difficult because Spence leased the apartment under Max’s name, according to property manager Sam Lesko. Spence, he said, forged tax documents suggesting that Max earned $400,000 a year. In addition, Spence left more than $11,000 in back rent for his Austin apartment—also under Max’s name—court records show.

Following Spence’s arrest, a tearful Max, accompanied by his mother, met with Lesko claiming he was a victim. Until that day, Max told me, he had no idea the apartment was rented under his name. When I mentioned that his old Austin property manager was also seeking unpaid rent under his name, Max seemed baffled.

With his credit score nearly ruined, Max says he couldn’t open a bank account. (His credit score is recovering now, he says.) “I got Anna Delvey’d,” he said—a reference to the notorious New York grifter exposed last year for scamming an international swath of socialites and bankers. “I was 24. Dan ruined my life.”

Spence declined the opportunity to be interviewed for this article and did not respond to messages sent through the Rutherford County, Tenn., Sheriff’s email system.

Meanwhile, Northside Media’s run is over, at least in its current format, says Stedman, its death knell sounded with Spence’s arrest. The Northside Festival won’t happen this month. “I know that myself and the many people who worked on Brooklyn Magazine and Northside look forward to celebrating this community in new and exciting ways,” Stedman said, offering gratitude for the people he’s teamed up with over the years.

For former Northsiders, the media company’s final chapter was a sad denouement. “We had great products and passion, but no capital,” said Holliday. “And here comes Dan, promising to make all our dreams come true. I pain to feel how Danny feels.”

This past April, Spence pleaded guilty to reduced charges in the Bartlett case. A judge sentenced him to five years, but allowed that prison term to run consecutively with the five-year remainder of Spence’s suspended 2016 sentence, which was reinstated. In Brian’s case, which is proceeding in a different county, Spence faces a sentence of six to 10 years, though it could drop if Spence agrees to a plea deal. His next hearing is later this month.

***

Not long ago, I met up with Casey Holliday in a Manhattan bar, the day before he was to start a new job. As it happened, Brian was passing through New York, so I invited him to join.

When they met, it was as if they were old war veterans who’d experienced the same battle with different platoons. Holliday sipped a Prosecco and Brian tippled an Old Fashioned. They both guffawed about “Uncle Roy” and Spence’s love for Popeyes and Range Rovers.

I suggested that Spence used the money he stole from Brian to court Holliday. “I guess I bought all those dinners,” reasoned Brian, patting Holliday on the back in a light-hearted moment.

More than anything, like almost everyone else I spoke with as I reported this story, they couldn’t figure out Spence’s endgame. Had he been planning to use the Northside deal to obtain a bank loan, disappear and pop up in another state with his mother? Was he after Stedman’s identity? Or was it all just a delusional ego trip—the fake asbestos ad guy reinventing himself as the fake badass magazine owner?

“I think he just sat at his computer and picked out people to use to make his imaginary life,” a high school friend suggested.

And then, there’s the question of how much money Spence ever really did have. “Between everyone, he’s got millions of dollars,” Justin Huffman suggested. “This was not a patty-cake operation.” But why the bounced checks? When I called Stephen M. Dalton, the Cleveland banker Spence flew to the Northside festival, he swore he had no recollection of Spence—until I mentioned his festival attendance, at which he said he couldn’t talk about former customers.

During a similar call, Stephen C. Jacobs, a lawyer for Herrick Feinstein—the law firm Spence retained during Northside negotiations—cited attorney-client privilege and declined to comment on the story, abruptly ending the call.

The thing is, there was much of Spence’s life that was true. KLS, at one point, was real. The tragic story about his sister’s death—that happened. His financial literacy and deep knowledge of the media industry is not in question. And when he said he had meetings with bankers, politicos and editors? He probably did.

But what of his relationships? “Was I a coincidence or did he target me?” wondered Holliday. “Did he like me? Or was I just maintenance to keep the deal going?”

Holliday isn’t sure he’ll ever get the answers. But he’s finally stopped wondering. “The only way I can make sense of it is by trying not to,” he said. “We always want to paint things in black and white, and they never are.”