Two leading rap musicians have released a short film and started a petition calling on the police to stop criminalising young black artists, who they say are being stifled by legislation that censors those who useviolent lyrics.

Krept and Konan’s petition on Change.org references the case of Skengdo and AM, who make drill – the darker, often bellicose sub-genre of rap music that originated in Chicago in the early 2010s before becoming popular in the UK.

Skengdo and AM were sentenced to nine months in prison in December for performing their song Attempted 1.0 at a London concert in breach of a “gang injunction” that banned the group from doing so because it was linked to “gang-related violence”. The petition calls the decision the beginning of “a clampdown on free speech for rappers”.

“Young people don’t get into serious crime lightly,” the petition reads. “They do so because of serious social problems … that is what’s driving the escalation of violence on London’s streets. The soundtrack is irrelevant.”

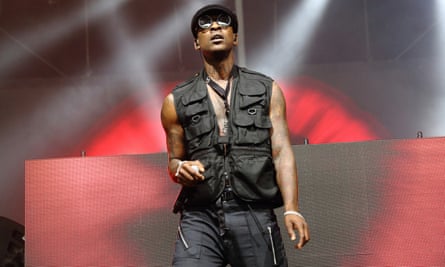

Speaking at the launch of their video Ban Drill, Krept and Konan said the song was inspired by Skengdo and AM’s legal battle over their music, and that criminalising music would hold back a new generation of artists.

“They’re stopping the next Krept and Konan, the next Stormzy, the next Skepta,” Konan said. “You’re stopping the potential. There’s not really many avenues to get off the street, music is the main one. When you stop that, you limit people.”

Rapman, who directed the video, said: “Would you rather have these so-called ‘bad kids’ on the street or in the studio? The police think that they need to do something, so they decide to try and ban the music. They’re doing more damage than good.”

Konan said: “When you’re on the roads and you’re doing this, no one wants to be doing it. No one wants to go to jail or get stabbed. That’s just the environment you’re in. When you’re doing music, touring and going to the Brits, do you think you’ll be thinking about committing crime or going back to that life? Of course not.”

The petition also refers to police use of the Serious Crime Act, which established the Serious Crime Prevention Order (SCPO), a civil order nicknamed the “gangster asbo”, which has also been used to target terrorist suspects. “We are asking you to stop the police from being able to ban drill music by using the Serious Crime Act to prosecute artists,” it reads.

The two rappers believe attempts to stop drill acts playing their songs continue a pattern, after police use of form 696, a controversial risk assessment that promoters and venues had to fill in from 2005 to 2017. It was scrapped after accusations that it was being used to racially profile urban music nights.

Konan wrote about the life-changing effect music had for him in a comment piece for the Guardian on Thursday. “Before music, there was just jail, gangs and getting arrested,” he wrote. “Without music, I do not know if I would be alive today. Best-case scenario, I’d be in prison.” He was also critical of police attempts to gag drill musicians. “To me, it’s just another version of stop and search, targeting a group of people without justification for a crime that hasn’t actually happened.”

Krept and Konan’s comments echo the open letter signed by Liberty which called the injunction against Skengdo and AM “demonstrably ineffective at tackling youth violence”. The civil rights group said it presented “a threat to all our civil liberties” that prevented young people from discussing “the reality of their lives with any hope of being heard”.

AM told the Guardian in January that he did not believe preventing certain songs being played would stop violence. “It’s PR [for the police],” he said. “If you’ve never been to this area, and you know there’s a crime problem because you read about it, it makes the police look like they’re doing something.”

YouTube has removed 30 drill music videos from its site after requests from the Metropolitan police. The force’s commissioner, Cressida Dick, said disputes conducted by young people on social media can escalate quickly and violently.

Krept and Konan are the latest rappers to speak out about drill. Giggs criticised the Sun last August for its coverage of the murder of the drill rapper Siddique Kamara, AKA Incognito, who was stabbed to death in Camberwell, south London. The tabloid’s front page claimed the DJ Tim Westwood and YouTube, which hosts drill videos, “profit from death”. Kamara had featured on Westwood’s video channel with his drill group Moscow17.

“It’s strange how when our music gets popular we make your shit newspaper,” he wrote on Instagram. “Black yutes were dying weekly and barely made the south London press, and what a surprise that it’s not about a kid losing his life, it’s just some bullshit story you made up about profit and Westwood.”

Five members of the west London group 1011 were issued with a court order earlier in 2018 that banned them from making music without police permission. The group have to notify police within 24 hours of releasing videos and give 48 hours’ warning of the date and location of any performance or recording, and let officers attend.