On YouTube, you can find a clip of Madonna appearing on American Bandstand in January 1984. She is still promoting her eponymous debut album, released six months before, and still just one among a raft of young singers mining a vein of post-disco dance-pop. She has yet to have a Top 10 hit in the United States, and the host, Dick Clark, still finds it necessary to explain who she is when introducing her. Her label’s expectations for the single she performs, Holiday, are so modest, it hasn’t bothered commissioning a video for it.

And yet it’s not just hindsight that makes the viewer realise something big is about to happen to her career. After she mimes to Holiday, the audience won’t stop screaming and cheering: Clark has to plead for quiet so he can interview her. Answering his questions, Madonna is funny and flirtatious and very, very confident. He asks her what her ambitions are. “To rule the world,” she answers.

Thirty-five years on, Madonna laughs when I mention it. “Yes,” she nods. “Sorry for saying that.” The thing is, she says, she wasn’t confident at all back then: it was all a front. “I may have been insecure, I may have felt like a nobody, but I knew I had to do something. If I was going to make something out of my life, I had to, you know, hurl myself into the dark space, go down the road less travelled. Otherwise, why live?”

She recalls feeling as startled as anyone else when she realised how famous she had become, less than 18 months after she had informed Clark she was going to rule the world. The Like a Virgin album had come out and sold 3.5m copies in 14 weeks in the US alone. She had scored six transatlantic Top 10 hit singles in under a year. Desperately Seeking Susan was in cinemas: her presence as the titular heroine had turned a low-budget film packed with cameos from New York underground luminaries – Richard Hell, Arto Lindsay, Ann Magnuson – into a box-office smash. No one was talking about her being just one among a raft of young post-disco dance-pop singers any more.

“It took my breath away. I can’t begin to tell you. I remember the first concert I did on the Virgin tour, in Seattle, when everything became big and I had no way of being prepared for it. It literally sucked the life out of me, sucked the air out of my lungs when I walked on stage. I sort of had an out-of-body experience. Not a bad feeling, not an out-of-control feeling, but an otherworldly feeling that nothing could prepare you for. I mean,” she smiles, “eventually you get used to it.”

You clearly do. The Madonna that sits before me, perched on an overstuffed sofa in a swish hotel not far from the house she owns in central London, certainly doesn’t give the impression of being a woman terribly plagued by insecurity: a solitary wobble comes when talk turns to her then-forthcoming appearance on Eurovision, a venerable television institution almost unknown in the US and that, it quickly becomes apparent, Madonna has never actually seen. “Well, Jean-Paul Gaultier is obsessed with it,” she shrugs.

Her unexpected, apparently unresearched and ultimately divisive plunge into the world of Ding-a-Dong, Dana International and nul points pour le Royaume-Uni notwithstanding, she radiates starry self-assurance. And why wouldn’t she? A list of her achievements in the intervening 35 years includes becoming the bestselling female artist ever, the most successful solo artist in the history of the American charts, the highest-grossing solo touring artist ever and, as she dryly notes, “still being alive”, her only real competition for the title of most legendary pop artist of her era, Michael Jackson and Prince, having both prematurely passed away.

Sometimes when she talks, she unmistakably sounds like a pop star forged in a different era. She is “dizzy” at the sheer turnover of pop in the digital age – “There are so many distractions, so much noise, so many people coming and going so quickly, it takes away the artist’s ability to grow” – and says the modern way of writing pop songs, where artists are thrown together with a rotating cast of random star producers and writers at songwriting camps, didn’t suit her at all. “Oh, I tried that on MDNA and Rebel Heart. I worked with a lot of talented people, but it’s too hard to have a vision when you work with so many people: there’s so much input. I didn’t enjoy the process at all. Sometimes it was great, but it’s very weird to sit in a room with strangers and go: ‘OK, on your marks, set, write a song together!’ You have to reveal yourself, you have to be vulnerable, and it’s hard to do that right away.”

She says the person she had the best experience with in the writing camps was Avicii, the Swedish EDM star who killed himself in April 2018. “I called his group of writers the Viking Harem – all these six-foot gorgeous blond men. I thought we wrote a lot of great songs together, but many of them never got finished. For a minute there, I felt like I was having that moment with one group of people, but then that switched, then it switched again and then it switched again. I didn’t like it.”

Nevertheless, uniquely among her peers, she is still resolutely a pop artist, still making music informed by what is happening in the charts and the clubs. These days, she sometimes learns about it via her 13-year-old daughter, Mercy, an “urban queen” whose taste in hip-hop apparently sits badly with her Elton John-loving brother, David: “He says the lyrics degrade women, and he’s right.”

“There’s nothing forced about it,” she says of her continuing quest to personify pop. “This is the music that I listen to in my house, this is the music that inspires me. Oh, you’re not allowed to make youthful, fun, sexy music if you’re a certain age? That’s a load of” – she dips into an English accent – “bollocks, to speak your language.”

And, whatever ups and downs her career has taken, she very much belongs to a select band of stars so impossibly famous that interviewing her is, by default, a discombobulating experience. Not because she’s difficult or unpleasant in any way; far from it. There’s no mistaking a certain don’t-mess steeliness, but she’s thoughtful and engaging. It’s just that she’s her. As she talks, I keep catching myself thinking: bloody hell, that’s Madonna.

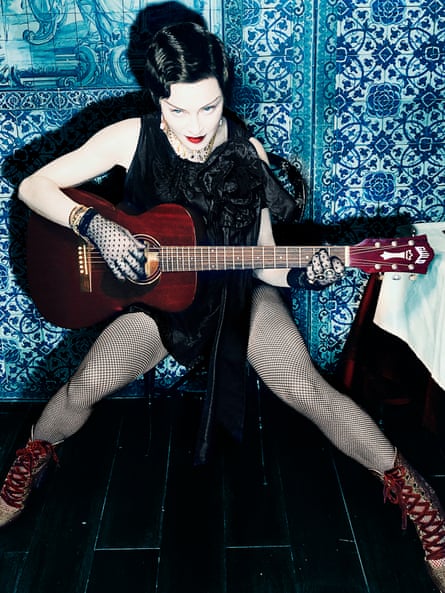

This state of affairs is compounded by the fact that she has turned up dressed as, well, Madonna, or rather Madonna as Madame X, the persona she inhabits on her new album, complete with the same bejewelled eyepatch that will subsequently cause Graham Norton to congratulate her for appearing at Eurovision “despite clearly suffering from a terrible case of conjunctivitis”.

Madame X is apparently “a secret agent, travelling around the world, bringing light to dark places, a spy in the house of love, curious, hungry for knowledge, wants to wake people up”. The album itself is a lot of things that fans want a Madonna album to be: provocative, personal, political, funny, quite eccentric and, as she puts it, “cheeky”, a charmingly decorous way of describing the lyrical content of Bitch I’m Loca, a track that ends with her urging the Colombian singer Maluma to “put it inside”. It reunites her with Mirwais Ahmadzaï, the French producer who worked on her two undisputed latterday classics – 2000’s Music and 2005’s Confessions on a Dancefloor – and serves up an eclectic grab-bag of mumble rap, reggae, post-Despacito Latin pop, pounding hi-NRG, an electronic version of Dance of the Reed Pipes from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, and fado, the latter influenced by her relocation to Lisbon two years ago.

She “100% moved there only for David” – he plays football for Benfica’s youth academy – and initially endured “a few months of lonely anguish, not really knowing anyone, not speaking Portuguese, trying to figure out how to fit in that world and make my children comfortable”, before making friends and being drawn into the city’s music scene. She talks enthusiastically about house parties “where you can’t move for musicians playing fado” and tiny bars without music licences where audiences are forbidden to clap the performers “so you have to rub your hands together as a sign of applause, which is pretty cool”.

The lyrics, meanwhile, variously touch on school shootings, the sitting US president, the decline in the value of celebrity, and sexual abuse and harassment. She’s not sure why the music industry hasn’t yet had a #MeToo moment to rival Hollywood’s. “It’s all the same – there are people abusing their power everywhere, in all areas of life, not just film and not just music. A musical artist is allowed to speak in a more personal way and be themselves and talk about issues in a way that say, an actor is not; they don’t have a voice, the voice and the opinions belong to the director or the studios. And if you’re a movie star and you want a part in a movie, there are a lot of people, mostly men, who are willing to exploit and abuse that power to degrade women. And they’re untouchable.”

She has recently spoken of how Harvey Weinstein was “incredibly sexually flirtatious” with her and “crossed lines and boundaries” when they worked together on 1991 tour documentary In Bed With Madonna. “Harvey Weinstein was untouchable. His reputation was universal – everybody knew he was, you know, the guy that he was. I’m not into name-calling, but it was like: ‘Oh, that’s Harvey, that’s what he does.’ It just became accepted. And I suppose that’s the scary thing about it. Because if people do things enough, no matter how heinous and awful and unacceptable it is, people accept it. And that certainly exists in the music industry, too.”

She came up against it herself in the years when she was trying to get a record deal. “I can’t tell you how many men said: ‘OK, well, if you give me a blow job’, or: ‘OK, if you sleep with me.’ Sex is the trade, you know? I feel like maybe there isn’t a movement so much because we’re already used to expressing ourselves in a way, or fighting for things, although I do wish there were more women in the music business that were more political and more outspoken about all things in life, not just … the inequality of the sexes.”

My time is nearly up, and our conversation turns back to the old American Bandstand footage of an ambitious 25-year-old. She says she still has ambitions: “Well, I’ve just put a record out, so I must still have ambitions. Yes, I want to be successful, I am ambitious. Yes!”

But you’ve been as successful as a pop star can ever hope to be – does that not curb your hunger a bit? She frowns. “But I don’t think my ambition has ever really been generated by what you maybe perceive as conventional success. I mean, being super-famous or super-rich was never my goal.”

Hang on a minute: you said you wanted to rule the world. “When I said I wanted to rule the world, I didn’t say: ‘I want to be the most famous person in the world.’ I didn’t say: ‘I want to be the richest person in the world.’ I said I wanted to rule the world.” She thinks for a moment. “Well, what did I mean then, in my very young mind? I think I just meant I want to make a mark on the world, I want to be a somebody. Because I grew up feeling like a nobody, and I wanted to make a difference. I think that’s what I meant.”

And with a handshake, she’s off, or rather, I’m off: politely ushered from the room, while Madonna sits on the sofa, immaculate, still sporting her eyepatch, looking as much like a somebody as it’s possible to imagine a human being looking.