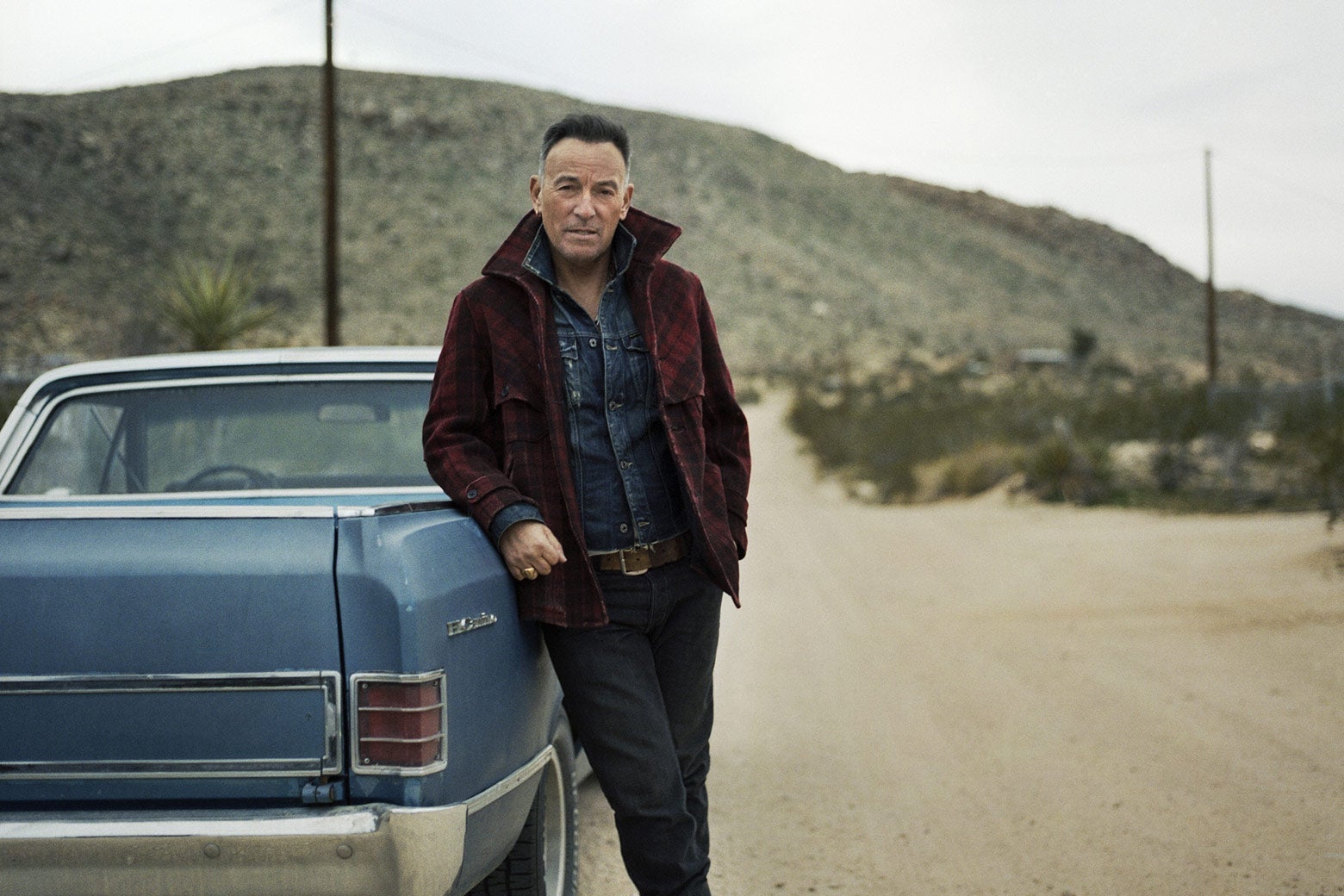

Bruce Springsteen has four or five basic musical styles, and he’s created imperishable songs in each of them. But the one I wince over the most is the acoustic balladeer who tries to channel the spirit of Woody Guthrie, with political references updated but affected twang intact. One of Springsteen’s most appealing moves in the past few years has been for the nearly-70-year-old star to acknowledge, in his memoir, Born to Run, and its stage counterpart, Springsteen on Broadway, that he’s always been partly a rock ’n’ roll Barnum. He is a showman who takes the stage in working-class drag (or as he puts it, in his father’s clothes), while in fact he’s never held a regular job in his life. It’s a sleight of hand that creates real magic. But Bruce’s dust bowl drawler, although modeled on some of the greats, tends to feel like a second, less-fitted costume pulled overtop the first. And then, though not always, it risks becoming baggy (carpetbaggy, one might say) and clownish, for instance on 1995’s The Ghost of Tom Joad, or the forced-fun hoot-a-nonsense of his mid-2000s Pete Seeger tribute album.

So when I heard that Springsteen’s first studio album in five years, and first of all-new material since 2012, would be called Western Stars, with song titles like “Chasin’ Wild Horses” and “Sleepy Joe’s Café,” I worried a bit that it was another mannered antiquarian exercise, maybe leaning less this time into Guthrie and more into Hank Williams and Gene Autry.

It turns out Western Stars, which comes out this Friday, does have a historical model. But it’s one much further inside Springsteen’s orbit and in his own professional lifetime. It’s the Los Angeles sound of the late 1960s and early 1970s—not the widely mimicked Laurel Canyon folk-rock style, but the more orchestrated, Nashville-influenced manner of Jimmy Webb and Glen Campbell, with dashes of Harry Nilsson and Burt Bacharach, among others.

California was where Springsteen’s parents migrated in his young adulthood, and it always has served as kind of a spiritual other, a sunnier flip side to New Jersey smog, in his imaginative landscape. Perhaps after all the introspective focus on his Jersey roots in the autobiography and the stage show, this felt like a natural sequel. It allows him to settle into the intimate singer-songwriter mood he favors for solo albums (as opposed to E Street Band outings), while winkingly acknowledging his Hollywood-bunkum side with the sweet strings. The choice might also resonate in subtle ways with problems in the political climate, but I’ll leave that case for later.

In any literal way, it’s one of Springsteen’s less self-revealing albums. And who could blame him for wanting a respite from the this-is-my-life business, after 500-plus confessional pages and 236 two-hour barings of his soul on Broadway? Instead, the characters here tend to be men adrift in Western states, in search of or, more often, on the run from their dreams. As he puts it on second track “The Wayfarer,” it’s the “same old cliché, a wanderer on his way/ Slippin’ from town to town.” The record is haunted by the Utopian romance of the Western frontier, but, because this is a Bruce Springsteen album, it’s encountered mainly in brokenness and loss. When the album is strong, which it is far more often than not, it manages to refresh those clichés, partly with lucid lyrical detail, but especially sonically. Foregrounding the orchestration (which is more panoramic than emotionally demonstrative) leads Springsteen in pleasantly unfamiliar directions, but seldom so far afield as to be jarring.

It eases in with opener “Hitch Hikin’,” which reminds me of the early Tom Waits circa “Ol’ 55,” with the music loping along like a pickup truck rolling through town, while Springsteen reminisces via homespun dialogues about a time when a young person could trust that thumbing it on the highway was a safe and benign way to get from point A to point B and discover a little of America along the way. The symphonic vistas open up further on “The Wayfarer,” which lays out the album’s thematic brief. Then it starts to dig into specifics. “Tucson Train,” an immediately classic-sounding Springsteen tale of yearning, finds a man who’s fled the “the pills and the rain” of San Francisco to operate a crane in Arizona anticipating—with excitement and perhaps trepidation—the arrival of his ex-lover on the 5:15 train. He’s found some kind of contentment working hard in the Southwest, and here comes the person with whom he “fought hard over nothing … till nothing remained.” Has he actually changed enough to handle it? The song ends on the ominous ticking of the clock.

The album’s gallery of solitary men gets even more grim and compelling with title track “Western Stars,” whose punning title refers not only to the nocturnal sky out past the Rockies but to celebrities from TV and movie Westerns. Its declining hero looks back on his scene with John Wayne (“it was towards the end”) as the high point of his life, but today he’s nursing a hangover with “two raw eggs and a shot of gin” while waiting to shoot a Viagra ad. On weekends he likes to head out to the desert to watch Mexican charros compete in rodeo events—another kind of “Western stars.” Other nights he might flirt with some “lost sheep from Oklahoma” in an L.A. bar, animal imagery that intersects menacingly with the previous line about a coyote crossing the narrator’s front porch “with someone’s Chihuahua in its teeth.” You could pair the song with another showbiz-derelict scenario with sexually threatening overtones, “Under Lime,” from Springsteen’s songwriting peer and one-time duet partner Elvis Costello’s last album, Look Now, although as usual Costello goes more directly for the jugular.

Less glamorous, though more sympathetic, is the situation of the guy in “Drive Fast (The Stuntman),” waxing wistful about his long-past daredevil glories and the girl who got away, but winding up with a couplet that’s one of Springsteen’s recent best, as he must know since he both starts and ends the song with it: “I got two pins in my ankle and a busted collarbone/ A steel rod in my leg, but it walks me home.”

How many songs by this artist famed for his highway-spanning, syllable-spilling epics and his marathon concerts clock in at under two minutes? There’s one here in “Somewhere North of Nashville,” a sparse miniature (with Springsteen’s rasp in full Steve Earle effect) about a songwriter who gives up love to pursue fame in Music City, where he fails more or less instantly. Now he’s splitting town with “nothing but this melody, and time to kill,” and precious few prospects of recovering what he’s squandered.

Western Stars ends with “Moonlight Motel,” an understated, fingerpicked ballad in which weekends of youthful erotic trysts at a stop “on a blank stretch of road/ Where nobody travels and nobody goes” give way to years of “bills and kids and kids and bills” and ultimately, it seems, to divorce. One day our forlorn protagonist rouses himself from his “lonely bed” to go revisit their former love nest, only to find “she was boarded up and gone like an old summer song.” He takes a bottle of Jack out of a paper bag and pours out a shot in the parking lot in love’s memory, and damned if it doesn’t choke me up just as a closing track oughta.

The album fouls out only when it (understandably) tries to break up the torrent of poignancy with something more upbeat. For instance “Sleepy Joe’s Café” is a vaguely Latin-style accordion groover about an idealized oasis “ ’cross the San Bernardino line” where working folk of all stripes can dance their cares away. It’s a concept similar to The Rising’s “Mary’s Place,” but the milquetoast “world music” arrangement and bland lyric make it eminently skippable. And that’s a masterpiece next to “There Goes My Miracle,” which seems to have wandered in by accident from Working on a Dream, Springsteen’s misfired attempt a decade ago to catch up with more current pop. While the melody has potential, the repetitively anodyne lyrics should be ashamed to keep company with the other songs on this album. And Springsteen strains for a bravura vocal that he maybe (maybe) could have managed in the 1980s, but not with his more worn and surgically compromised instrument in this century.

The one positive-minded track that clicks is “Hello Sunshine,” which was released as the initial single in April and epitomizes the record’s California country template. Some listeners have pointed out how it recalls “Good Time Charlie’s Got the Blues,” the 1972 hit by the otherwise little-known singer-songwriter Danny O’Keefe. But Springsteen’s take is a reversal—about breaking instead of contracting an addiction to melancholy. If you’ve read his book or seen the theater production, “Hello Sunshine” clearly seems to be about transcending the severe depression Springsteen went through several years ago, and the destabilizing effects of his own chronic restlessness. In this sense, it serves as the bridge between the album’s broader themes and his personal life.

So what, then, about the political angle? Given his legacy, it’s startling that the first new collection of Springsteen tunes since Donald Trump captured the presidency is absent of any overt sign of protest. And in many ways it seems the better for it. What could Springsteen have sung that he hasn’t sung before, as recently as 2012’s Wrecking Ball, about inequality, elite deception, immigration, the betrayed American social contract, and yet somehow finding hope? A more troubling consideration for Springsteen himself might have been that Trump’s populist schtick isn’t entirely unlike his own legendary crowd-rallying powers in full “the Boss” mode, except with the politics through a fun house mirror. Toward the end of last year, he was fretting that none of the Democratic presidential candidates could match Trump’s talents on that level and the Donald might have 2020 on lock. This more long-view-taking album might represent a sabbatical from ideological rhetoric while he mulls over that dilemma. Indeed, he might be keeping his powder dry for next year’s actual election cycle, when, he’s suggested, there may be a new E Street Band album and tour.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

On another level, though, Western Stars’ tight focus on white masculinity in crisis might also reflect a meditation on Trump Nation, the anxieties that feed it, and how its demographics overlap with much of Springsteen’s own constituency. It’s notable that his decision to make a (kind of) country album happens to coincide with the pop phenomenon of Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road.” The controversy about that chart topper’s country credentials has amplified an argument some fans and analysts are calling “the yeehaw agenda,” which attempts to correct the record on the roles of people of color in America’s frontier and rural history and culture. That debate, like Springsteen’s investigations here, addresses the urgency now of reckoning with who can lay claim to the fantasized American “heartland,” for what purposes, and with what consequences.

That this album doesn’t hit such points more head-on might frustrate those activists and fans who prize Springsteen’s outspokenness above all else. But Western Stars has the patience to dwell on painful questions without surging toward premature answers, with musical settings that help listeners linger there too. Coming from an artist whose ability to overdo a good thing has been at once his superpower and his kryptonite, that seems like aging gracefully.