In the first year of the 21st century my American editor and I sat in a restaurant talking about Michael Jackson. We hailed his uncanny brilliance and mourned it too – 30 years of making music, dance, film; crisscrossing styles, genres, types and tropes; confounding cultural codes. We brooded over the rumours and scandals that were turning him into an object of derision, even revulsion. We wanted, we said, to give him his due before (my editor’s words) “he self-destructs … Before he’s destroyed,” my editor qualified, “and self-destructs.”

Events moved too quickly: I couldn’t finish the book before he was arrested in 2003. He was indicted in 2004; he was found not guilty in 2005; he was found dead of an accidental drug overdose in June 2009. We hoped death would restore the measure of his greatness as an artist.

In the quiet, sombre documentary Leaving Neverland, released earlier this year, two young men in their 30s look into a camera and describe the childhood years in which they had sex with Jackson. They use that flat phrase, “had sex”, and they describe, almost wonderingly, how much they loved him, even worshipped him. They make us understand how often and how much sexual abuse depends on a child’s looking up to a powerful adult: trusting, needing, maybe loving that adult. Molestation and abuse are harsh unambiguous words, but we can’t fully understand them unless we understand that they are often inseparable from the lures and ambiguities of seduction. These feelings get all mixed up in a child’s mind and body. So we must not separate the acts and the aura of seduction from the acts and aura of abuse. Jackson was a cultural deity. And of course these boys were thrilled to be in his presence: millions of people – twice, thrice and four times their age – were thrilled to have him in their presence, if only via computer screens, concert stadiums and memorabilia. Imagine meeting Jackson face to face. Imagine being the child whom a god chooses as his favourite.

To any child, there is something of the god about every powerful grownup – be they parent, mentor, patron or counsellor. Wade Robson and James Safechuck were child performers from ordinary families. The Jacksons had once been an ordinary family and world fame had chosen them through Michael: now Michael was choosing their children. He visited their modest homes; he watched TV, goofed around and ate popcorn with them. The families were besotted. He brought them all gifts and took them on trips. He offered them a fairytale of upward mobility. The Jacksons had lived that fairytale – why shouldn’t they? He made the families feel special. He made the boys feel loved. Did he love them? Within the confines of his damaged, damaging soul, I imagine he did. We like to think we love with all that’s good in us. But we love just as fiercely with all that’s bad in us. “Childhood is the fiery furnace in which we are melted down to essentials and that essential shaped for good,” wrote Katherine Anne Porter. She should have added two more words. She should have added “and ill”.

In the video for a song he wrote and titled “Childhood” Jackson sits in a lush green forest, clad in white, and sings softly and longingly to the camera:

It’s been my fate to compensate, For the Childhood I’ve never known Before you judge me, try hard to love me The painful youth I’ve had …

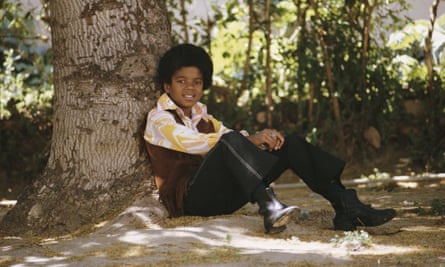

It’s our fate now to reread his videos and song lyrics, probing for coded confessions. “Have you seen my childhood?” he asks twice, in sad, sweet, boy-soprano tones. In a court of law it could be his plea for exoneration. For in fact we know a lot about Jackson’s childhood. We know what it cost him to be the family’s ticket out of poverty and obscurity.

We know he was beaten and psychologically tormented by his father, Joseph. According to persistent rumours he was sexually molested by at least one adult in the music business. So yes, we can say that, like Robson and Safechuck, he could not free himself from his experience of childhood abuse.

Instead, he recreated it. What began with Joseph Jackson was passed on by Michael Joseph Jackson. The son who kept surgically cutting away at his face partly because he didn’t want to look like his father did not cut away this legacy of abuse: he passed it on to another generation of boys. A tragic tale and a horrifying one. The predator-seducer pretending to be the pure-hearted protector of innocent children everywhere. I say pretending – and Michael was a peerless performer – but I think he also longed to be the pure-hearted protector of children’s innocence. That longing gave his pretence an uncanny power for a long time. It’s a power he still exerts over the masses of fans whose feverish rebuttals and teeth-bared denunciations can be found online.

The vulnerable genius was also the calculating paedophile. That’s what we must reckon with now, what we must refuse to simplify.

¶

Jackson, one of the 20th century’s greatest – most exhilarating, innovative and influential – popular artists was first accused of the sexual abuse of Jordan Chandler in 1993. He was 35 years old. A financial settlement was agreed. Ten years later, in 2003, he was arrested and charged with sexually molesting another boy, Gavin Arvizo. The 15-week trial that began on 28 February 2005 was an immersive and clamorous multimedia spectacle. Everything Jackson owned, from his penis to his art collection, was examined and photographed by the Santa Barbara police department. Reports on their findings, some official, some leaked, went global. The trial was televised daily with frenetic commentary. Eighteen months and 21 days after his arrest Jackson was found not guilty of all charges.

TimelineMichael Jackson child sexual abuse claims

Show

After Jordan Chandler makes allegations during a police interview that Jackson has abused him, an investigation begins. Jackson had met the 12-year-old boy the previous year.

Teenagers Brett Barnes and Wade Robson hold a press conference stating that they had shared a bed with Jackson on multiple occasions, but that nothing sexual had happened.

A lawsuit from the Chandler family alleges sexual abuse by Jackson and seeks $30m.

Jackson describes being strip-searched and photographed by the LAPD two days earlier as “the most humiliating ordeal of my life”. He states: "I am not guilty of these allegations, but if I am guilty of anything it is of giving all that I have to give to help children all over the world.”

Jackson settles out of court with the Chandlers for $22m – $15m goes to Jordan Chandler to be held in a trust fund until he turns 18.

After two grand juries fail to indict, and Jordan Chandler tells authorities he will not testify in court, the Los Angeles and Santa Barbara district attorneys end their investigation.

The lead single from Jackson’s album HIStory is released. A duet with his sister Janet, the song angrily addresses media coverage of the child sexual abuse allegations against him.

Jackson discusses regularly having sleepovers with children, including a young cancer patient named Gavin Arvizo, in Living with Michael Jackson – a documentary fronted by the British journalist Martin Bashir. "It's not sexual," said Jackson on-screen. "We’re going to sleep. I tuck them in. It's very charming." The film rekindles police investigations.

Jackson's Neverland estate is again searched by police, and a week later Jackson is arrested.

Michael Jackson is formally charged with committing lewd and lascivious acts with a child under the age of 14.

During Jackson's trial, Arvizo and his younger brother testify that the singer showed them pornography and made them drink "Jesus juice" – wine. Both say Jackson masturbated in front of them and molested Arvizo on multiple occasions. Blanca Francia, one of Jackson's former housekeepers, testifies she saw Jackson showering with Wade Robson. Witnesses for the defence, including Macaulay Culkin and Robson, say that Jackson never molested them.

The jury finds Jackson not guilty on all 14 charges brought against him.

In the run-up to This Is It, a planned residency at London's O2 Arena, Jackson dies age 50 of a cardiac arrest.

Wade Robson takes legal action against the Jackson estate, alleging that Michael Jackson molested him over a seven-year period between the ages of seven and 14.

Safechuck alleges Jackson abused him on more than 100 occasions after the pair met when Safechuck appeared in a Pepsi commercial alongside the singer.

Dan Reed's four-hour documentary Leaving Neverland opens at the Sundance film festival. In it Wade Robson and James Safechuck discuss at length the abuse they claim they suffered at Jackson's hands. It is described as "a public lynching" by Jackson's surviving family.

Leaving Neverland is shown on the HBO network in the US, with a UK screening on Channel 4 on 6 and 7 March. The Jackson estate sue HBO for $100m, claiming the network is in breach of a non-disparagement clause in a 1992 contract.

Radio stations around the world, including in New Zealand and Canada, begin to pull Jackson's music from the airwaves.

But being found not guilty by a court is a far cry from public exoneration. He had been disgraced. He was in debt. He made people squeamish. His record sales wavered and dipped. Nothing was beyond the shadow of any sort of doubt. Supporters insisted that the financial settlement was his only way of avoiding further exploitation. Doubters and opponents pointed out that surely more investigation was needed: there had been lawsuits, multiple rumours and Jackson’s unabashed admission that he shared his bed with boys. He couldn’t be tried again. The case moved to the court of public opinion.

And he moved about like exiled royalty – Bahrain, Las Vegas – plagued by debt, dependent on the hospitality of royals and moguls. He became an iconic figure in celebrity scandal-and-downfall narratives. There was the male sexual downfall narrative, which took in 20th-century stars from Fatty Arbuckle to Roman Polanski, Jerry Lee Lewis to Chuck Berry. There was the drugs and body disfigurement narrative, represented by Elvis Presley and by every ageing female star mocked for addiction problems and cosmetic surgeries. He was all but expunged from journalism’s official narratives of pop innovation and glory.

When I wrote my book I was grieving for Michael Jackson the artist. The uncanny little boy; the charismatic, slightly mournful young man, the shape-shifting child-man-woman-cyborg-extraterrestrial. The cultural polyglot who studied – mastered, gloried in – so many styles and traditions; one to whom no form of popular music and dance was alien.

I was grieving and I was confounded. Jackson’s acts and actions were like hieroglyphics we kept trying to decipher. We – for I was a fan, too – wanted him to explain himself in a way that could restore our trust. Child stars make us believe we understand them, that there’s mutual trust between us. We were baffled by our collective memory of Jackson the loving, lovable child who was now shutting himself off from us.

I was relieved, I was grateful when he died. He can get it all back with his art now, I thought. We can glory in that. And we did. Death restored his reputation as an artist. In the years that followed his grisly 2009 death – the overdose, the frantic attempts at CPR, the corpse in the body bag, the lurid autopsy details – there was a Jackson renaissance. Pop, jazz, and hip‑hop musicians adapted and sampled his songs; two generations of dancers recycled and recharged his moves. Multiple ways of reading his art sprang up and flourished. Academics began reading him through deconstruction, post-colonial and queer theory; performance, gender and cultural studies. He became the avatar of a transracial, transgender and trans-species world.

But now, 10 years after his death, Leaving Neverland has placed new demands on us. Am I chagrined and shamed that when I wrote my book I couldn’t push myself to acknowledge that this damaged man was almost certainly a sexual predator? Of course I am. As a critic I’m invested in believing I’m not in the grip of naivety or denial. I tell myself that at least I wasn’t alone. A lawyer friend observed recently that in the 1980s and 90s the sexual abuse of children was still (his words) a black hole in the culture’s consciousness. That black hole had a fierce gravitational pull: we circled around it, but we did not peer down it to deepen our knowledge of its social reach and psychological intricacies.

The crises that have created #MeToo and similar movements show how little we knew and how little we chose to know about … what’s the range of words? Sexual harassment, exploitation, molestation, assault and abuse, across all divisions of class, gender, race, ethnicity, religion and age. We know that few of the victims, perpetrators or complicit bystanders are famous. The famous ones can turn the story into a public tragedy that stirs our pity and terror. But no catharsis is available.

What happens now? Some people say they need to “cancel” Jackson, stop listening to him, stop watching him for a time. Some radio stations and streaming services have done just that. Fashion houses have withdrawn clothes that bear his image or (too obviously) his influence; statues have been pulled down in several European countries. But these are short-term actions.

In the meantime, Robson and Safechuck have sued the Michael Jackson estate, and in response the estate has denounced them and sued HBO for $100m. Like many, I am rooting for these men to win any legal and financial recompense they possibly can. Such recompense is usually the only form of public justice available to sexual abuse victims.

Finally, there are long-term cultural questions that plague us, questions about the relation between art and life. Usually, these questions take the form of: can we, should we separate the life from the work? And how would we do this? Can we grapple with these questions and not hide behind old-school simplifications? According to these simplifications:

1) We must not separate the life from the work because history has shown that the art will inevitably reflect the corruptions of the life. (This is usually followed by a list of the ethical and political ills that art can wreak on society.)

2) We must separate them because art is on the side of freedom; it offers beauties and pleasures that transcend the confines of moral disapproval. (This is usually followed by a list of major artists who have lived their lives as fascists, Nazis, misogynists or white supremacists while producing major art.)

Art versus life is too simple. Are we talking about our personal opinions and judgments of the art and the life? Or do we mean opinions shaped by social systems, by law, politics and history? We need the intelligence and the will to make these distinctions – in ourselves, not just in the art we choose. What makes us love or hate an artist? What makes us love and hate an artist, feel pleasure and unease, confusion and bliss all at once? What private needs and longings do we each bring to the work we love? When the dark materials of a life pervade, even taint the work, does that mean we must cast it off? It might mean that, but it might also mean that we fight for the parts of it that matter to us. We gather our resources in all their plenitude and variety: intellectual, emotional, moral; aesthetic, political. And we use them to analyse and demystify the work, to probe its clashes and contradictions, feel their power without being at their mercy. No evasions, no simplifications. The task is to read the art and the life fully as they wind and unwind around each other, changing shape and direction.