The first time I saw a live streaking event was on the Tuesday of my first finals week at the University of Notre Dame. I was an 18-year-old freshman who had seen maybe four instances of full frontal male nudity in her entire life, and two of them had definitely been accidental. I’d surmise most of my female classmates at the very Catholic university were in the same boat.

[Start Your #RWRunStreak With Us]

Still, we crowded the second floor of the Hesburgh library, eagerly awaiting the promised parade of Alumni Hall men trotting nude through the wide-open study space named after a priest. We were giggling. We were whispering. We couldn’t wait.

I don’t know what I was expecting, but it turns out that a large group of nude men, many of whom were covering their heads with such accessories as sombreros and oversized Yoda masks, isn’t that enjoyable to watch, especially when they’re jogging. I felt bad for them. It looked like it hurt. And after it was all over, I congratulated a friend of mine who had participated, like he’d just completed a difficult task.

And he had. Not in the same way a runner accomplishes something in the traditional sense. Running’s most dignified iteration involves running toward a medal stand, a finish line, a PR. Slightly less dignified but still impressive is the act of running away from something: a bear, a vice principal. Then there’s a third way to run, the act of running through something for the purpose of disrupting or entertaining. The kind of event we lined up for all the way back in the early aughts.

Yes, streaking—the kind people first think of when you talk about run streaks, and the silly counterweight to the emotional heaviness of giving your all. Just as an asthmatic pug is the same species as a greyhound, so too is streaking in the same species a Kipchoge marathon. It is running’s wacky cousin, its quirky neighbor. And it’s a reflection of how seriously we take our own rules, and ourselves.

Running through a public space fully or partially nude has a long history with motivations to match the era. During the 15th century, the Adamites protested the Holy Roman Empire’s buttoned-up morality by running naked through their Bohemian village, as Adam and Eve would have intended, if Adam and Eve, like the Adamites, had regarded monogamy as a sin. Historians say Quakers—Quakers!—revived the practice in the 17th century, protesting the Church of England and often urging onlookers to repent.

America’s first streaker was a Washington & Lee (then called Washington College) student named George William Crump. Though his motivations were lost to time, he was suspended for a semester after being arrested for running nude through his college town in 1804. But don’t worry about Crump. He would go on to become a doctor and, later, a congressman.

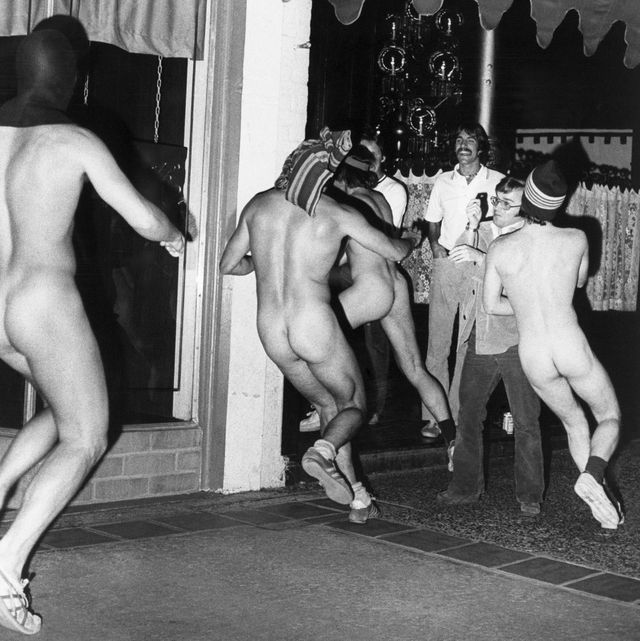

By the 1960s, American college students would rediscover the Adamite joy of gathering in groups and running naked through public places, much to university administrators’ chagrin. Observers can’t pinpoint exactly why young adults suddenly decided to take their clothes off and run around in nude groups, but it could have been due to several factors: changing attitudes toward sexuality and nudity, generalized distrust of authority and institutions, and the fact that streaking tended to garner a lot of media attention, which begat more streaking. People love attention!

But 1974 was the year that streaking went from a countercultural campus joke on The Man to full-on craze, like pet rocks or Slinkies. Streaking made the cover of Life magazine. A solo streaker even interrupted the 1974 Oscars, in an incident that some say was a pre-planned way for the award show to grab the zeitgeist, like a stadium security guard grabbing a nude interloper.

Around this time, streaks became more organized, involved more people, and transformed into spectacles. It became such an “epidemic” at Stephen F. Austin State University in Texas that college administrators made time and space designated for a nude run. (Think “The Purge,” but bouncing genitals instead of murder.) The largest group streaking event on record occurred in March 1974 at the University of Georgia, when 1,543 people got naked and went for a jog. My Fighting Irish were beset by the streaking craze then as well, and I can imagine that Our Lady’s first batch of female students, admitted in 1972, probably felt as shocked by all the library dong as I was 30 years later.

Streaking thrived through the 1970s and evolved as we approached the Reagan era. During the Me Decade, streaking expanded to become a “Me” activity, a way for a person to claim 15 minutes of fame.

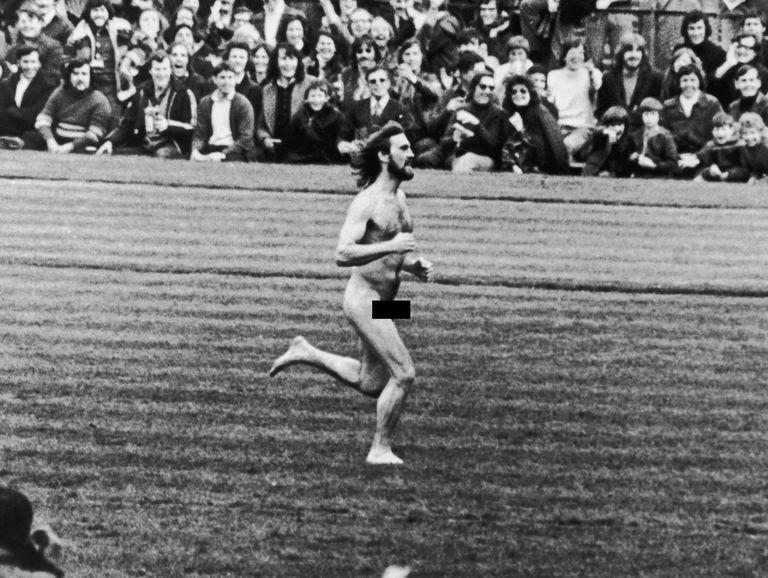

The first notable sporting event to be interrupted by an attention-grabbing solo streaker was the England-France rugby match at London’s Twickenham Stadium in—of course—1974. An Australian named Michael O’Brien made good on a bet with an English friend when he ran nude onto the pitch around the match’s halfway mark. As O’Brien was hauled away, a police officer placed his hat over the man’s nethers, which led to one of the most iconic photos of streaking, if not all of sports, in the 20th century.

This laid the foundation for the modern superstar streaker. The most successful is Mark Roberts of Liverpool, England, who has streaked more than 550 events since he started with a Hong Kong rugby match in 1993. He’s streaked soccer games, golf tournaments, Wimbledon, the Olympics, and a Miss World beauty pageant. At the end of halftime of Super Bowl XXXVIII, Roberts darted onto the field dressed as a ref, stripped down to a thong, and danced in front of a stunned Panthers kickoff squad before a Patriots linebacker tackled him. He was arrested, charged, and fined $1,000; pennies when you consider that sponsor GoldenPalace.com paid Roberts $1 million for the stunt. Roberts has become so notorious that security around big sporting events in the U.K. are given his photo in advance.

Roberts is a purist, streaking for the love of entertaining crowds during an event’s lull. He doesn’t interrupt in-progress games, nor does he bear any political messages—just the occasional paid—beyond “Hey! A naked guy!”

Today’s streakers are, no surprise, driven by social media, with a dash of politics. Take Vitaly Zdorovetskiy, known more commonly by his YouTube username VitalyzdTV, who disrupted a 2016 NBA finals game in Cleveland, Ohio, by rushing the court in a state of semi-undress, with TRUMP SUCKS sharpied on his chest and LEBRON 4 PRESIDENT on his back.

With 1:12 left in the fourth quarter and the Warriors with a comfortable lead, Zdorovetskiy made his move, barreling out onto the court and ripping his shirt off, running a few strides before being tackled to the ground by a swarm of security.

Zdorovetskiy’s breathless five-minute video on the two-second shirtless event has 7 million views on YouTube. It’s not the heyday 1970s anymore, but people still love the brave chaos of a mid-event streak.

Despite its resilience, there’s a lot about streaking that feels passé. Streaking is very white and very male. Yes, there have been notable female streakers, such as Erica Roe, whose topless run through a 1982 England-Australia rugby match earned the nickname of “The Twickenham Streaker,” despite Michael O’Brien’s groundbreaking work. And in 2000, Jacqui Salmond ran onto the 18th green at St. Andrews, interrupting the British Open and ticking off Tiger Woods—who, in retrospect, might have been better served by minding his own morality. But by and large, it’s a sport for white men because it’s easier for them to sneak into the sidelines of sporting events without being hassled by security guards. Just as it’s easier for them to go about the world without being hassled, or remain confident law enforcement will give them a fair judgment. It’s not streaking’s fault. It’s the world we live in.

While streaking of the 1960s and ’70s seemed to be driven by a the same spirit of fun and adventure that compels a 3-year-old to take all his clothes off and run fully nude into the middle of his parents’ dinner party, there’s something a little off in our increasingly enlightened culture about forcing a person to look at one’s naked body without the permission of the observers. Especially considering that being forced to look at nudity isn’t always that fun for observers.

Now, at Notre Dame, the much-gawked-at Bun Run of old has become a source of on-campus controversy and moral hand-wringing. Understandably so. Some people just want to study during finals!

There are also safety concerns for large public events where everybody’s naked. Princeton University had to axe its Nude Olympics in 1999 after seven students were hospitalized due to injuries obtained ostensibly while nude. There’s also the injury to a reputation or criminal record; ending up on a sex offender list is not worth the adrenaline rush of briefly interrupting a soccer game with your peacemaker. That perhaps explains the trend of today’s streakers, like Zdorovetskiy, leaving their goods under wraps instead of going full flop.

Streaking embodies the opposite of what runners love about running. Road and trail races require months of planning and bring strangers together to cheer for other strangers who have been training for months, if not years. Strip all the dignity from running—the self-discipline, commitment, sportsmanship, order—and what do you get? A 19-year-old sophomore in a foam cowboy hat who may have flunked his organic chem final that morning but, for a glorious few minutes, is greeted like a hero breaking the tape at Boston.