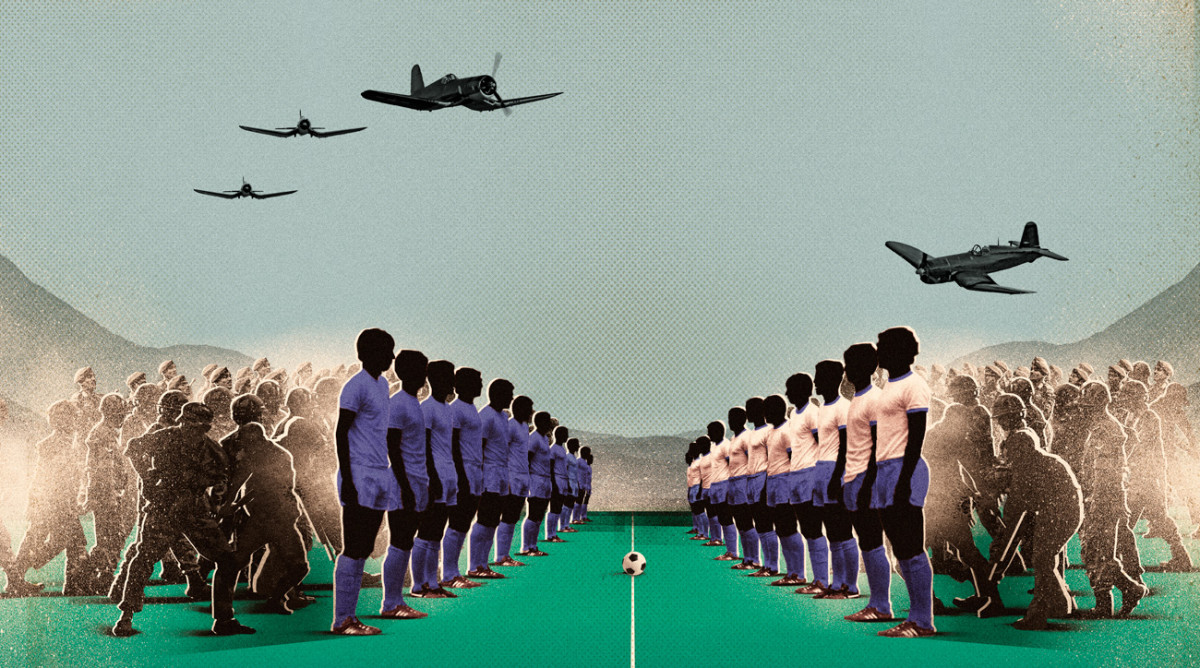

Soccer. War. Nothing More.

This story appears in the June 3-10, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

It rained hard in Mexico City on June 27, 1969, the night the men's national teams of Honduras and El Salvador played for the chance to become the first Central American side to participate in a World Cup. It was the second-most important conflict being waged between those two countries at that moment—and by far measure.

The first half at Estadio Azteca was played calmly, considering what was at stake. Players displayed none of the fervent nationalism that had been stoked by their respective governments back home, none of the animosity that had exacted a grave human toll already and would turn even worse in the days ahead.

“On the field, we respected each other,” says Salvador Mariona, the now-75-year-old captain of that El Salvador team. “Even today, the ones still alive [from that Honduras team], we have a strong friendship.”

El Salvador wore royal blue, trimmed in white; Honduras wore white, trimmed in royal blue, the common colors of their national flags. The countries also shared the same language, the same religion, with similar cultures—commonalities that would only make it more difficult to understand what followed two weeks later.

A few thousand soccer supporters, mostly Salvadoran, made the 700-odd-mile trip northwest for the match, the deciding contest in a three-game series. They joined Mexican locals in filling about 15,000 of the lowest seats of a stadium that held 100,000. In the eighth minute they all watched El Salvador’s tall, loping striker, Juan Ramón (Mon) Martínez, receive the ball unmarked at the edge of the 18-yard box and rocket a left-footed shot under Honduran keeper Jaime Varela’s ungloved left hand, inside the far post.

Back home, as Salvadorans danced beside their radios celebrating the early 1–0 advantage, the armies of both nations—carrying the same weapons and wearing identical uniforms—stood poised across their jungled, 243-mile border.

Earlier that month, the Honduran government had begun kicking Salvadorans out of its country, hundreds at a time, then thousands, often with a nudge from a military rifle. The reason: They weren’t Honduran.

Central America, a thick rope of seven countries that links North and South America, was not a stable place to begin with. Even on a map, El Salvador, the smallest and most densely populated of these nations, appears under pressure, with the larger Guatemala and even larger Honduras (nearly five and a half times El Salvador’s size) pressing down on it from above, smushing it into the Pacific. Farmable land in El Salvador was not only scarcer than in Honduras, it was also controlled by a wealthy elite that for nearly a century had told the country’s poorest farmers they weren’t welcome.

By the 1960s, some 300,000 Salvadoran peasant farmers—campesinos—had relocated to Honduras, where they could farm freely. And in ’67 Honduras passed a land- reform law that essentially asked all those people to go back home. The Salvadorans did not abide, so in ’69, Honduran president Oscar López Arellano, an impatient sort who’d gained power six years earlier by military coup, decided to force them out. This unfolded as the two nations were advancing through the first round of Concacaf qualifying, past countries like Suriname and Costa Rica, destined for one another.

In the days leading up to their first head-to-head, in ’69, handbills appeared throughout Honduras. The first printed word was a slang term for a Salvadoran.

Guanaco: If you believe yourself decent, then have the decency to get out of Honduras. If you are, as the majority are, a thief, a drunkard, a lecher, crook or ruffian, don’t stay in Honduras. Get out or expect punishment.

The first wave of expulsions came on June 2 as 500 Salvadoran families were forcibly moved from Honduras to the other side of the border. Game 1 would be played six days later, in the Honduran capital of Tegucigalpa, the home team winning 1–0. Fans of both sides clashed in the streets before, during and after the match, just as they did after El Salvador’s 3–0 victory in Game 2, a week later in San Salvador.

The situation at the border—the increasing deportations and the lack of room for the deported—deteriorated so dramatically that on the day of the deciding third match, in Mexico City, the Salvadoran government severed diplomatic relations with Honduras, accusing its neighbors of “crimes which constitute genocide.” Recalls Mariona, the Salvadoran captain: “We were focused on qualifying, but we knew the conflict was there.”

Following the Martínez goal that drew first blood, Honduras looked disorganized. It didn’t have the fleet of attackers El Salvador had—men like Martínez, Mario Monge and Mauricio (Pipo) Rodríguez, who could score from anywhere. Honduras claimed only one player like that. It had brought José Enrique Cardona onto the team just two weeks earlier, shipping him home from Spain’s fabled Atlético Madrid club. “He was on another level, as he had been playing in Europe,” Mariona recalls of the man nicknamed la Coneja, the Rabbit. “And that was reflected in the match.”

Eleven minutes after Martínez’s goal, the 5' 5" Cardona set up beneath a cross lofted into El Salvador’s penalty area and executed a blind bicycle kick, smacking the ball out of the air and driving it backward into the net. Goalie Gualberto Fernández could only drop to all fours as the scoreboard changed to read: EL SALVADOR 1, HONDURAS 1.

Within hours of the first expulsions, back in early June, Red Cross refugee centers on the Salvadoran side of the border had been overwhelmed. Local newspapers and radio stations seized on this opportunity to defend their nation’s honor and demonize their Honduran oppressors by claiming that the expulsions were murderous pogroms of mass rape and mutilation. But the director of the Red Cross, Baltasar Llort Escalante, said he saw no evidence of such atrocities at the refugee centers or at Salvadoran hospitals. According to the definitive 1981 book about the conflict, The War of the Dispossessed, by Thomas P. Anderson, violent human rights abuses by Honduran authorities “were isolated cases and not so widespread as generally believed in El Salvador.”

Honduran newspapers like El Cronista, meanwhile, reported “with unseemly glee” (Anderson’s words) on the “cleansing of the alarming number of Salvadoran campesinos who have infiltrated our soil” (the paper’s words).

“The media definitely fueled the fire at a time when people in power needed that animosity to be inflamed,” says Dan Hagedorn, who cowrote The 100 Hour War.

Fearful of an influx of returning squatters, El Salvador’s powerful landowners threatened President Fidel Sánchez Hernández with a coup if he didn’t attack his neighbors. Hernández’s Honduran counterpart, López Arellano, needed the public to loathe Salvadorans so he could forcibly remove them (and also to distract his own people from his self-serving leadership).

Salvadorian nationals who were residing in Honduras arrive at the Red Cross headquarters in San Miguel on July 7, 1969. Following the armed conflict between El Salvador and Honduras, 14,000 nationals residing in Honduras returned to their country.

Alfredo Quant/AFP/Getty Images

The site of the first match of the qualifying series, Estadio Nacional, was turned into an internment camp for Salvadorans. June in Central America means intermittent rain and temperatures in the 80s. The venue had no roof, limited facilities and, now, a throng of intimidated refugees.

A Human Rights Subcommittee within the Organization of American States would later state that “the press and radio bear an enormous responsibility” for the war that lay ahead. Following El Salvador’s victory in Game 2, “Radio Tegucigalpa spoke of ‘the enormous quantity of [Honduran] vehicles destroyed [in El Salvador], of violated women and sadistic beatings, of men brutally wounded by the crowds,’” Anderson wrote. “El Cronista, as usual, outdid everyone else, speaking . . . of hungry and thirsty Hondurans being served urine and manure, of women stripped and violated in the streets by Salvadoran mobs. Those of us who were there saw nothing of the kind, but it was impossible to intrude any rational statements into the Honduran press.”

Polish war journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski would later tell his own stories of abuse, but their veracity was called into question when he wrote that the restless Salvadoran crowd had held up “portraits of the national heroine Amelia Bolaños” before Game 2. Bolaños, according to Kapuscinski, was a teenager who took her own life, using her father’s pistol, moments after her beloved team lost Game 1. The Amelia Bolaños story, shared in Kapuscinski’s 1991 book The Soccer War, has since been debunked. No birth or death records exist for such a person. The massive public funeral that Kapuscinski said the Salvadoran team attended—it never happened. The newspaper he cites as his main source, El Nacional, appears to have been entirely made up.

Kapuscinski’s book, an anthology of war reporting from around the world, contains the most prominent example of the misunderstanding that has taken hold over the past 50 years: that two countries took up arms against each other because of a soccer competition. The misleading title, The Soccer War, has since become ubiquitous. Even those who take issue with its accuracy use it. Anderson—student of Central American politics and history professor at Eastern Connecticut State University—was a devout enemy of the term (until his death in 2017), and yet he employed it throughout The War of the Dispossessed, even as his book title tried to rename the conflict, even as he wrote on page one that the conflict “was not over something as trivial as football.” That handy label proved as irresistible to him as it has been for the rest of the world over the last half century.

The first hint that the beautiful game would be blamed for the war came three days before the climactic match, when the Salvadoran National Assembly put forth a resolution—which members must have known was untrue—declaring it “lamentable” that Hondurans were retaliating against Salvadorans as a “result of the recent international football games.”

The confusion was furthered by a brief UPI story that appeared in American newspapers the morning after the match. That report hinted at off-field tensions between the two countries but did not cover their cause. The headline dubbed the game the soccer ‘war.’

Only a single outburst marred the match in Mexico City, according to that UPI story: a brief shout of “Murderers! Murderers!” from a bloc of Salvadorans. One can only guess, but that chant likely stemmed from media reports of slain Salvadorans in Honduras, or from the confirmed atrocities committed by the Mancha Brava, a Honduran vigilante group that doled out death on behalf of the López Arellano government.

One of the most commonly repeated errors of the whole ordeal is that FIFA had moved Game 3 to Mexico City because of the tension. The truth is that the rubber match had been scheduled for a neutral site many months earlier. The war was still more than two weeks away when Honduras and El Salvador met in Mexico City, but by this time saber rattling at the border had devolved into mortar fire and skirmishes among ground troops that left handfuls of casualties. “It was a coincidence that this was happening while we were trying to qualify to the next round,” explains Mariona, trying to dispel the countless references online and in the foreign press to the soccer game that started a war. “War was already brewing.”

Salvador Mariona was El Salvador's captain as it qualified for the 1970 World Cup.

Marvin Recinos/AFP/Getty Images

In the 28th minute, with the score still knotted at one, Mon Martínez found himself dribbling in space, with only a single defender between him and the goal. The mercurial striker, who would go on to play for the Indiana Tigers of the American Soccer League, made it past his opponent, outran another Honduran and ended up one-on-one with Varela. Martínez’s right-footed blast made it 2–1, El Salvador.

Early in the second half, a long pass by Honduran midfielder Donaldo Rosales was misjudged, then mishandled by Fernández, the Salvadoran goalie. Rigoberto Gómez pounced on the gift and booted it into an empty net for the equalizer, 2–2.

Neither military was particularly well equipped for war. Nonetheless, the Salvadoran Air Force (FAS) began prepping a small fleet of civilian Cessna planes for combat. They rigged special seat straps and removed passenger-side doors, turning single-engine light aircraft into bombers: A pilot had only to tilt the plane, release the strap on one of the football-sized mortar rounds seated next to him and shove the shell into the sky.

The Salvadorans also relied on the same P-51 Mustangs that had escorted American bombers over Europe in World War II. This would be the last war, anywhere in the world, in which prop planes were used. Here the Salvadorans employed an eccentric American plane restorer named Archie Baldocchi as a consultant. The 55-year-old Californian had married a Salvadoran woman years earlier and had fallen for her homeland, too. Baldocchi served the war effort by retooling one of his prized Mustangs and configuring other old warbirds for fresh fighting. He also helped recruit a handful of American fighter pilots to the cause—thrill seekers with spare time—promising them, on behalf of the Salvadoran air force, $2,500 for each Honduran plane they removed from the sky.

On the morning of July 14, FAS mechanics readied the big American planes for battle and loaded ordnance onto Cessnas, Pipers and other puddle jumpers. The plan was to strike at sunset, then fly home under the cover of darkness. “By 5:50 p.m.,” Hagedorn reports in his book, “31 Salvadoran aircraft were on their way to their assigned targets.”

Five minutes after Fernández’s adventurous net-minding allowed Honduras to tie the match, a new goalie, Jorge Suárez, came on for El Salvador.

“The downpour converted the field into a skating rink,” recalls Monge, now 80.

The game was becoming more physical, but the Mexican referee, Abel Aguilar Elizalde, did not raise a single card the entire match. In the 75th minute, following a hard tackle on Cardona, Elizalde blew his whistle and jogged over to the scene, eager to continue the game. But the Honduran goal machine stayed down, curled in a ball of pain. Eventually he was carried off the field. He would not return.

The Hondurans pressed forward without their star. Suárez made a point-blank save of a shot that would have tilted the game in the 81st minute. In the 88th he punched a free kick over the crossbar.

It was here, recalls Monge, that his teammates remembered “the Salvadorans suffering in Honduras.” And this, he says, “led us into a winning state of mind. We kept telling each other, ‘Tenemos que ganar, tenemos que ganar.’” We have to win.

But first: Elizalde glanced at his wristwatch and gesticulated like an orchestra conductor. Ninety minutes would not be enough time to decide the victor.

Thomas P. Anderson was interviewing a government official in San Salvador when he heard the “angry roar of internal combustion engines in the sky,” followed by air-raid sirens. An hour later the radio informed locals that their country had just bombed Honduras.

Dan Hagedorn was at his desk near the Panama Canal when he heard the click-clack of a nearby teletype. The 23-year-old U.S. Army information specialist and historian-in-training was stunned by the words being inked across paper.

El Salvador’s air raid was messy and disorganized, foreshadowing the four-day confrontation that followed. In rural Central America, everything turns pitch black when the sun goes down, and the air war that dominated the conflict was fought largely in this dark. Even in daylight, the hostilities in July 1969 were typified by randomness and indiscretion.

“There were a lot of rounds fired, lot of bombs dropped,” says Hagedorn, five decades later, adding that innocent civilians were often caught in this crossfire. “All of a sudden their little campesino hooch would be destroyed by a plane flying over, and they had no idea what was happening.”

The rest of the world, meanwhile, was looking elsewhere. To Vietnam. And to the heavens. As morning broke on the second full day of conflict, July 16, Apollo 11 was launching from Cape Kennedy, Fla., carrying Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins to the moon. A classified CIA report from that day passed along news that Honduran authorities were still “rounding up all Salvadorans and detaining them in the soccer stadium. A nationwide Honduran radio network last night exhorted civilians in the western highway area to grab machetes or other weapons and move to the front to assist the army.”

But by then there was no need. Just two days later, at 10 p.m. on July 18, the two governments begrudgingly agreed to a cease-fire. Each side was down to its last bullets and bombs. “Each side,” says Hagedorn, “was exhausted.”

The match in Mexico City remained knotted as the first of two 15-minute extra periods trickled away. With four minutes remaining, El Salvador’s José Antonio Quintanilla won the ball in the center circle and booted it forward, high and long. His teammate Roberto Rivas chipped a back pass to Elmer Acevedo, who crossed it toward the penalty area.

The Hondurans’ last defender didn’t see Pipo Rodríguez (the Pipe, for his slim silhouette) slipping behind him, sprinting toward the goal, and so he allowed Acevedo’s ball to float right past his face, thinking his keeper would collect it. But there was Pipo, baseball-sliding in with the toe of his right boot, nudging the ball beneath Varela’s hands and into the back of the net, 3–2. Photographers rushed the field. Rodríguez lay on his back near the goalmouth. A teammate fell on his chest, embracing the hero as he thrust both arms skyward.

Four more tense minutes remained to be played, then an additional 15 after that, with the Salvadoran defense turning away some of the Hondurans’ ripest scoring chances. At the final whistle, the exhausted Honduran players stopped jogging, like toy soldiers in need of a windup, and sat on the wet grass. Pipo came over and consoled several of them. UPI’s “Soccer War” story noted that the match “ended in embraces and handshakes by both teams.”

The editors of El Salvador’s La Prensa Gráfica chose not to focus on the uplifting nature of the home team’s victory. HONDURAS ELIMINADO, the front-page headline blared. In essence: they lost—another editorial choice that served to inflame tensions.

"The war didn’t start because of our games," says Monge. “There was a political motive. It just happened to be during the time of the qualifiers.”

“I think we were used,” recalls Rodríguez, the hero. “The government used us as their voice. It happened in Honduras as well.”

Cristian Villalta, editor at the Salvadoran paper El Grafico, explains: “This was two military dictatorships using the games to exacerbate nationalism.” Calling it the Soccer War, he adds, is “like saying World War II broke out because of the artistic failure of Adolf Hitler in Vienna. It’s nonsense.”

And yet, sighs Mariona, “the press continues to make the same mistake.”

That mistake has had a far-reaching impact. It muddied the motivations behind a conflict whose final death toll hovered between 2,000 and 3,000, the majority of victims noncombatants. In 2001, retired U.S. diplomat Robert Steven told an oral historian, “It was a difficult job trying to get anybody in Washington . . . to take [that conflict] at all seriously. Everyone had the same reaction: Oh, it’s crazy in Central America, banana republics having a war over a soccer game or something.”

Not only have the causes of the conflict been wildly misunderstood, but the war itself also resolved nothing. Many Salvadorans stayed in Honduras. Military scuffles continued over the next decade. A peace pact wasn’t signed until 1980—and even that didn’t stick. The border remained in dispute until ’92. Diplomatic relations finally resumed that year, nearly a quarter century after the war “ended.” (The two national teams didn’t play between 1970 and 1980.)

Over the last 50 years, the region’s unchecked social imbalances and broken political machinery have allowed a new scourge, gangs, to take root. Migration to surrounding countries has continued to skyrocket. More than two million Salvadorans and Hondurans came to the U.S. in 2018—almost 80 times the number that made the trip in 1970.

The soccer outcome, too, proved anticlimactic. El Salvador’s victory over Haiti in the final Concacaf qualifying stage brought some measure of happiness and pride to its citizens, but the team’s return to Mexico City for the 1970 World Cup merely provided a new flavor of chum for the game’s larger, better-trained and better-funded soccer federations. The Salvadoran players were destitute. Mariona recalls that he and his teammates had to petition their own federation, historically rife with corruption and graft, for the 2,000 colones (roughly $230) that FIFA awarded each participating player. Their World Cup results in June 1970 reflected this lack of support: three games, three shutout losses.

As for the war and the international confusion about what caused it, says Mariona, “it’s almost a forbidden topic in El Salvador. Our biggest happiness was qualifying for Mexico ’70.”

“As I recall that moment,” says Monge, remembering his embrace of teammates in the rain, “I feel like I’m back in the Azteca stadium. Both teams wanted to win, but we were thinking about El Salvador and the conflicts at home. The team looked toward the small group of Salvadorans that had come to the game. They were singing and chanting. I can still see my teammates crying. Crying out of happiness.”

Additional reporting by Rafael Trujillo