My first meeting with Joss Sackler—of those Sacklers—is supposed to be for coffee at the bar of the Lowell Hotel on East 63rd Street, near Central Park. I arrive at five o’clock and find her already seated, wearing a white baseball cap that says K2, a vintage Blondie T-shirt, jeans, and a pair of oversize aviators with pink lenses that make it hard to see her eyes. To her right is one of her publicists, Elizabeth Tuke (pronounced TOO-key), a young woman with bobbed blond hair who specializes in fashion brands. There is also Goce Zojcheski, who is introduced as “working for the Sackler family.”

With some reluctance, I had sent over questions earlier in the day, and they had been vetted by Tuke and the Sackler PR team. But when I reach to turn on my recorder, Joss holds up her hand and says, “Hold on a second.” She removes her sunglasses and asks me, essentially, why I’m here. Valid question.

It’s not a great time to be a Sackler. For decades, if you knew the Sackler name, it was probably because you saw it engraved on a towering museum wall or a university building—there is the Sackler Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Serpentine Sackler Gallery in London, the Louvre’s Sackler Wing of Oriental Antiquities in Paris, and plenty of others.

But now members of the side of the family that owns Purdue Pharma stand accused in numerous lawsuits of helping fuel the opioid crisis by using deceptive marketing to promote the opioid-based drug OxyContin as non-addictive, then doubling down on sales efforts even as evidence mounted that the drug was being abused. And while the charges themselves are not new—Purdue and three of its top executives pleaded guilty in 2007 to criminal charges and paid a $634 million fine—it has been only recently that the focus has turned to the family.

But the specific reason I’ve been trying to speak with Joss is the Facebook post. On February 20, Matthew Schneier, a reporter for the New York Times Style section, wrote an article titled “Uptown, Sackler Protests. Downtown, a Sackler Fashion Line.” He described a collection of activewear that Joss had unveiled at New York Fashion Week under the label LBV, her nascent clothing brand. He also brought up recent protests directed at Joss’s husband’s family, which owns Purdue Pharma. (“If Mrs. Sackler’s name sounds familiar, it is probably not for the reasons she would like,” Schneier wrote.)

The next day Joss posted a letter on Facebook. “Dear Matthew Schneier:” it began. “If a male entrepreneur’s business was prospering and popular, would the New York Times dare publish an article so focused on the family business of his wife?”

“I was flattered that you came to our LBV presentation,” the post continued, “but what better truth for this sad media reality than what you have done here—using the same bait-and-click language to malign LBV, my own women’s initiative unrelated to Purdue, aimed at promoting women’s empowerment. What you accomplished in your bait-and-switch text was to relegate my identity to only being someone’s wife, thereby erasing any signs of my successes or accomplishments as a woman.”

Reaction was swift and partisan. “Your response to this is super brave,” one reader commented. “Don’t let this asshat get to you.” A Twitter user: “Should have written ‘Meet Joss Sackler, who just unveiled her hideous own fashion line made possible by blood money.’”

This is a problem for a very particular class of people: You have a lot of money, or a piece of artwork, or a patch of earth. The source of this money/artwork/earth is from a generation older than you, or it’s your generation but you married into it—you’re a beneficiary—and there’s a problem with the source. They were Nazis, for example. Or slaveowners. Or, in this case, made highly addictive opioids, and allegedly marketed them as safe. You weren’t a part of this, but now, like it or not, it seems you are. What, exactly, are you supposed to do? How are you supposed to act? How much of your life must you devote to apologizing, justifying, defending?

Can you just go about the business of living your life, even though the life you have would not be the life you have if it weren’t for all that money?

At the Lowell bar, a group of people sit down next to us and start loudly ordering drinks. Joss, who is 34, frowns at them and says a few times, “I can’t hear.” She sics Tuke on the problem, and Tuke runs off—twice—to see the maître d’. Finally Tuke returns and reports that the only place they can move us to is the restaurant, a fabulous French place called Majorelle, which is run by restaurateur Charles Masson, formerly of La Grenouille. And we’d have to have dinner. Fine, says Joss, and grabs her coat.

We’re led into a room full of early diners—arched ceiling, white tablecloths, lots of plants—and seated at a corner table with a banquette. Joss suggests wine, then argues over whether she will be the one to choose it. She is a trained sommelier (Level II), but she asks, “Are you going to write about what I choose? Or describe how I look off into the distance angrily when the name Sackler comes up?” (Schneier, in the Times: “When the question [of her name] is put to her, Mrs. Sackler falls silent and looks away.”)

Both publicists jump in with frequent clarifications and “off the records.” When they address her directly, they sound more like friends talking. (“You have got to do something about your assistant. She can’t even spell February,” Tuke says about a recent e-mail. “I know, I know,” Joss says, laughing.) She orders a bottle of red, and some kind of chicken. She is clearly still upset about the Times article. “I knew something was up, because the paper would not refer to me as Dr. Joss Sackler,” she says at one point. “I told them I have a PhD in linguistics.”

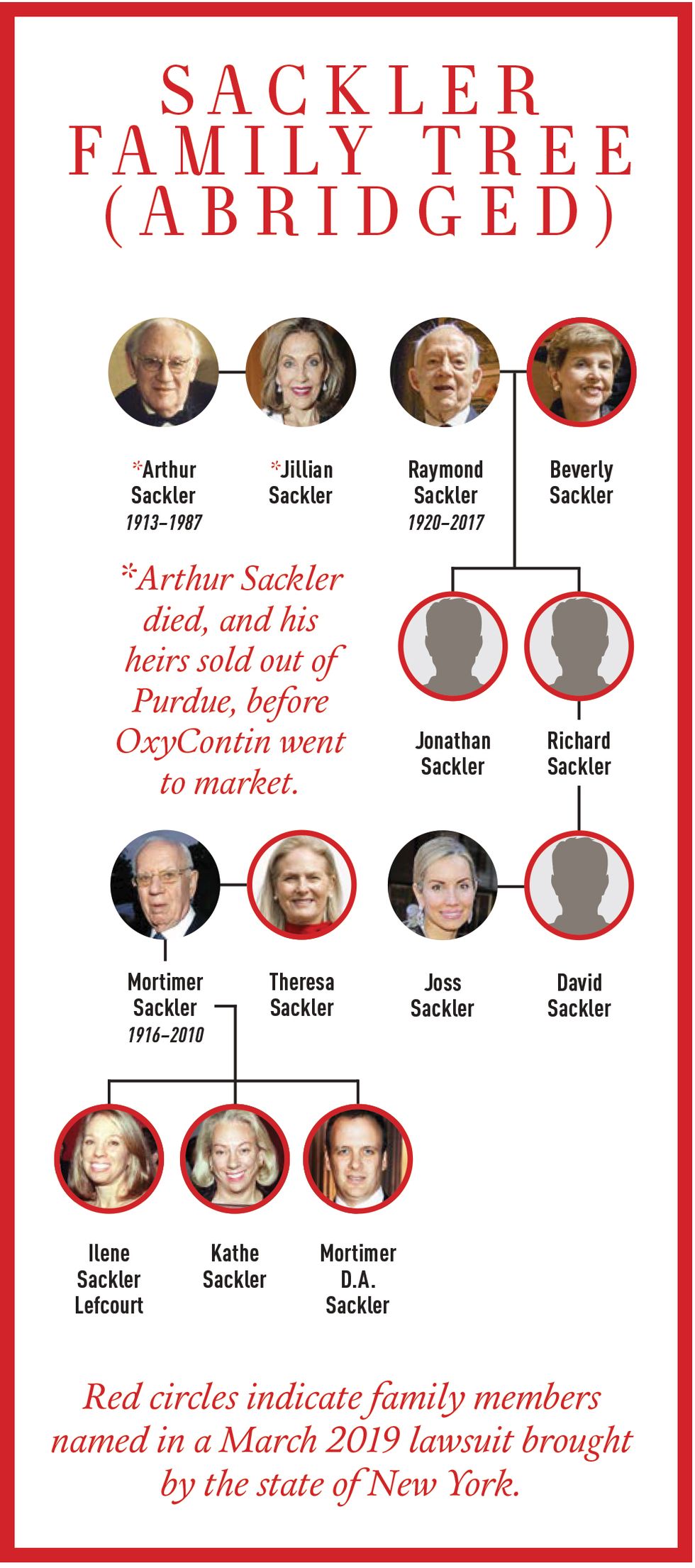

The eight Sacklers named in the recent lawsuits, including Joss’s husband David, vigorously deny all the allegations and say they will defend themselves in court. But it’s a big family, with members who never worked at the company and a whole branch that sold out before OxyContin went to market.

Some, like Joss, have asked to be judged on their own merits. “I support my family 500 percent. I believe they will be completely vindicated. But they have nothing to do with LBV,” she says, artfully steering the conversation to what she would prefer to talk about.

LBV began as a social club Joss co-founded in 2017. Its original focus was wine, but it has evolved into an organization that supports its 50 or so members’ endeavors. Recent events have included private visits to art galleries and a party to celebrate one member’s summiting of K2 in Pakistan. “We have mountain climbers, artists, and fashion designers,” Joss says. It was with this group in mind that she created LBV Care of Joss Sackler, her first foray into fashion. “There’s a handbag that also works as a diaper bag,” she notes.

After about 30 minutes and into a second bottle of wine, Joss begins to question why this article should appear in the Philanthropy issue of Town & Country. “I mean, David and I both have things we support, but I’m not the person to speak to about the Sackler family philanthropy. Why don’t you do a big piece instead on LBV?”

She pulls out her iPhone and starts showing me photos of herself shot by Lynn Goldsmith, the famous rock ’n’ roll photographer, who has spoken out in support of Joss’s Facebook post. In one shot she is topless. In another she’s seated between an artist and a 91-year-old woman, both of whom she is collaborating with on an upcoming performance piece.

She says, “Why don’t you put that in the magazine? Why don’t you put that on the cover?” Tuke jumps in, looking a little panicked. “Joss, Joss, I don’t think that’s how it works,” she says. But Joss goes on. “I think Town & Country is too old-fashioned for this. Have you looked at Playboy recently? I really like what they’ve been doing. It really has some grit.”

At first, most of the public scrutiny and litigation around OxyContin was directed at Purdue. But in 2017, Esquire and the New Yorker published in-depth articles about members of the Sackler family, including the three patriarchs, brothers Arthur, Mortimer, and Raymond (David’s grandfather), who owned Purdue Frederick, which later became Purdue Pharma.

In 2018 the artist Nan Goldin began staging protests at institutions that had received money from the Sacklers. Her activist group, PAIN (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), gathered in the Met’s Sackler Wing and threw fake prescription bottles into the Temple of Dendur reflecting pool. They staged a die-in at the Guggenheim and dropped leaflets printed with “Sacklers Lie, People Die” from the museum’s spiral walkway. Goldin was escorted out of a movie theater in New York after protesting about the screening of an unrelated documentary made by Madeleine Sackler, a granddaughter of Raymond Sackler.

The protests coincided with the announcement of major lawsuits against the Sacklers. Then, in March 2019, an art world earthquake: Three institutions that have received generous donations from Sacklers over the years—the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Galleries in England, and the Guggenheim in New York—announced that they would no longer take Sackler money. And just this week, the Metropolitan Museum announced it would not longer accept Sackler donations.

Joss is not the only Sackler who feels unfairly judged as a result of all this. Dame Jillian Sackler, who was the third wife of Arthur Sackler, has stated repeatedly that she should not be included in the blame for the opioid crisis. Arthur died in 1987, before OxyContin was developed, and she and his heirs were bought out of Purdue before the drug became available. “Arthur was an amazing man who did tremendous good, and I am just so proud of him,” she says.

Jillian lives in a 12-story neoclassical apartment building on Park Avenue where each floor is its own apartment. I’m greeted by a maid and ushered into an enormous wood-paneled living room lined with statues and paintings. At the far end of the room a trio of upholstered chairs is arranged around a low table. Jillian greets me—“Hello, I’m Jill”—and asks me to please be seated. Janet Wootten, her publicist, who works for the giant New York–based PR firm Rubenstein, takes the third seat and picks up a pad and pen. The table is set with delicate green china cups and saucers, and there’s a small plate of butter cookies.

Jillian is a towering figure in the world of philanthropy, praised both for making generous donations and for her facility at getting big projects completed. After the maid pours us coffee, this highly accomplished dame of the British Empire actually hands me a copy of her CV, a single-spaced page crowded with the names of foundations she and Arthur started and with her numerous board appointments, some of which date from the 1980s.

In the past two years alone she has helped celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology at Peking University and the reopening of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, and co-hosted the black tie centennial celebration of the Foreign Policy Association, of which she is the chair.

Things started going badly about two years ago. “I was approached by the director of the Sackler Gallery in Washington, and he said, ‘Jill, what is this? What’s happening here?’ I said, ‘Arthur’s got nothing to do with it. This is all totally wrong. This is all wrong,’” she says. She had similar conversations with members of other boards she’s on. “As I far as I could make out, they all believed me,” she says. In the beginning Jillian tried correcting articles that lumped Arthur and her in with the Purdue side of the family by calling the writers herself. Finally she hired Rubenstein, which now combs the news and makes frequent demands for corrections.

Not everybody agrees with her description of events. In September 2018, Goldin told ArtNet News, “But [Arthur] was the architect of the advertising model used so effectively to push the drug. He also turned Valium into the first million-dollar drug. And a similar drug, MS Contin, was released while he was alive, which was only a few molecules away from OxyContin. The brothers made billions on the bodies of hundreds of thousands. There are now 175 people dying a day. The whole Sackler clan is evil.”

Jillian refutes this characterization and any assertion that Arthur or she profited from OxyContin. She points out that no one on Arthur’s side of the family has been named in any of the more than 1,600 lawsuits that have been filed against Purdue, members of the Sackler family, and other pharmaceutical companies. Nobody has asked her to step down from a board position, and Harvard and the Smithsonian have both made statements saying they will not remove the Sackler name from their buildings.

I ask what she thinks the future holds, whether she’ll continue her philanthropic work. She seems flustered. Philanthropy has become enmeshed with who she is, and now that her philanthropic activity is being threatened she is not sure what that means for who she is as a person. “I don’t know the answer to that,” she says. These days, she says, when she is out in the world, “I barely dare mention my last name.

The day after my dinner with Joss, Tuke e-mails to say that Joss has agreed to do an actual interview. We plan another meeting—for lunch this time, at Maialino, the Danny Meyer Northern Italian restaurant on the ground floor of the Gramercy Park Hotel. Joss again wears her white baseball hat and jeans. She looks relaxed and kisses me hello on the cheek, and we order glasses of Santa Maria La Nave, a Sicilian white. She takes a sip and says, “What do you want to ask me?”

Joss was born in Canada. Her father was a diplomat, and she lived in Bangladesh and Kenya and went to high school in Japan before returning to Canada to attend university. She studied political science and wanted to join the CSIS, the Canadian equivalent of the CIA. But she chose linguistics instead and enrolled in the graduate program at the City University of New York. She was living in Park Slope when she met David on a blind date. “I was an adjunct lecturer at the time and was always running late. David is this super-punctual finance guy who is always on time,” she says, telling a story she has told a million times before. Punch line: “Thank god he waited.”

Joss didn’t change her last name for the first five years of marriage. “I didn’t want preferential treatment while I was doing my dissertation,” she says. “David’s grand-father was this highly regarded scientist and businessman. He was knighted in France and in England and had 12 authoring doctorates.”

She continues, “The first part of our marriage, while David’s grandfather was alive—tremendous respect, outpouring of love and everything through David’s grandfather. We would go there for weekends and he would have scientists there, actively discussing whatever the topic was that week.” Her dissertation was on threat language used by the Mexican drug cartels—research that has proved useful in recent years, she says. “I’m on Facebook and Instagram, and I’m particularly accessible.” She takes a sip of wine and eats a bite of burrata.

“There was somebody who was sending me superlong, very threatening messages. He found out who my climbing friends were and reached out to them with something like, ‘If you support Joss Sackler and her blood money, I’m going to call the local REI’—where they live—‘and make sure that nobody hires you as a guide.’ I’m a tough cookie, okay? I’m not intimidated or scared. But I realized that my friends were being hurt just by association with me.”

Joss found the person’s real name, she says, by Googling his screen name. “One day he sent this really long message, and I responded with a simple note.” The next thing she knew, “I get a call from [Purdue] security being like, ‘Um, this guy called, and he’s really scared for his life, and he wants to possibly go into a witness protection program because you sent him a threat.’ And I’m like, ‘One second. I get, like, 50 messages a day. My friends are getting messages. And I just responded to this one guy.’ ” She shakes her head and laughs.

Over two more glasses of wine and pasta with roast suckling pig, public perception is a recurring theme. I ask several times about her response to the Times piece and whether she thinks the negative articles will keep coming. “They’re going to regret fucking with a linguist,” she says. “They already do.”

At 6:30 p.m. on Monday, April 1, the doors open to the Metropolitan Building, a warehouse turned party space in Queens. Two large men in black suits step outside and begin checking names as a stream of guests arrive. The invitation featured a picture of Joss in a white dress with a see-through skirt and read: “Joss et Ses Amis: Undeterred, Featuring Live Performance by Interior Designer Eleanor Ambos and American Artist Tom Taylor, Black Tie, $700/Guest, LBV Curated Wines.”

Eleanor Ambos being the 91-year-old owner and curator of the space, Tom Taylor being a New York artist. Inside, tables are lit with candles and strewn with flowers hand-dipped in wax. Waiters, wearing white shirts with black vinyl sleeves pulled over the arms, serve drinks and hors d’oeuvres. Joss, dressed in a shimmering blue gown designed by Elizabeth Kennedy, greets guests at the door. The disconnect is jarring between this scene and what is transpiring at the same moment, all over America: thousands of people desperately searching for more OxyContin, their families wrecked, their money gone, their lives ruined.

At 7:30 the crowd is ushered into a room with rows of chairs facing a stage. The DJ lowers the music, and Joss climbs onto a circular wooden platform, as if she were about to throw a discus. Ambos begins to whistle a German folk song into a microphone, while Taylor uses scissors to cut great pieces off of Joss’s gown. After he has removed the bottom third, he begins burning holes in the remaining parts using a blowtorch. The platform begins to rotate, and Taylor spray-paints Joss and the now-destroyed dress.

Joss had planned this as an homage to Alexander McQueen’s famous 1999 spring fashion show, which culminated with the model Shalom Harlow being spray-painted by two large robotic arms. This version is smaller in scale and a lot weirder, but there is something mesmerizing about these three people interacting onstage.

The smell of paint grows stronger, and Joss starts to weave. After a few close calls, she falls off the platform and onto Taylor. The crowd gasps, but she gets her bearings, takes off her high, black, shiny boots, and climbs back up. Everyone cheers.

Later, a smaller group gathers for dinner at a long table. Each place is set with multiple wineglasses, which the waiters fill with an assortment of rare wines provided by an LBV member. One of Joss’s climbing friends, Lisa Thompson, mentions that she joined LBV because she likes Joss’s pro-woman message. “I know I have felt dismissed in the past because I’m a woman in the climbing world,” she says. I ask if she has read the recent articles about Joss’s family, and she nods. “I know a lot of people have distanced themselves from Joss, but I think it’s exactly moments like these when you have to stand by your friends,” Thompson says.

At one of our meetings before the party, I asked Joss if she thought things were going to get worse for her as more and more articles appeared about her family. She referred to her letter to the Times posted on Facebook and to the attention she is trying to garner for LBV and the fashion line. “It’s not to say that I’m shielded from negative sentiment that comes by having my last name,” she said. “What I’m saying is that at least now, when people use my last name, they will sure as hell use my first name as well. And that’s a win.”

After the dessert has been cleared, a group of women congregate around Joss. She is laughing and talking with Theodora and Alexandra Richards, models and daughters of Keith Richards and Patti Hansen. Then Ambos comes over and whispers in Joss’s ear. Quite suddenly Joss stands up and, with drama, pulls down part of her dress to reveal her left breast. She turns slowly so the whole room can see, and her guests cheer and whoop, and a smile spreads across Joss Sackler’s face.

This story appears in the Summer 2019 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW