Joe Elliott (singer, Def Leppard): The New Wave of British Heavy Metal (NWOBHM) was a phrase invented by Sounds magazine [in May 1979]. It’s an easy hook for many bands that came out around 1979, at a time when nightclubs were starting to let bands play again after disco had shut it all down.

Cronos (singer/bassist, Venom): Everybody said heavy rock was over. They said punk killed rock. That was the way everybody was talking.

Robb Weir (guitarist, Tygers of Pan Tang): The bar at Newcastle City Hall would be rammed when a hard rock band started soloing. We’d see Whitesnake, and Jon Lord would go into his keyboard solo, when we just wanted to hear songs. When the solo sections finished you’d down your pint and go back for the next song.

Biff Byford (singer, Saxon): Our icons were people like Black Sabbath, Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin. Our own music was quite similar to those bands when we first started writing but it developed into something different later in the 70s. The punk thing happened, which we were aware of – the energy and throwing yourself around on stage. Back in the day a lot of bands didn’t move on stage and you sat cross-legged on the floor watching them. We hated all that.

Brian Tatler (guitarist, Diamond Head): I remember hearing Symptom of the Universe by Black Sabbath, and it was the heaviest song I’d ever heard. I wanted to write something heavier than that. We got into writing fast songs. We’d go and see Judas Priest and they’d have fast songs that were very exciting – Exciter was ultra fast. I took quite a lot of energy from punk as well. The simplicity appealed to me, the fact you didn’t have to learn to play to an incredible standard before you could get on stage. That gave me a kick in the pants.

Joe Elliott: When you hear the energy of the Undertones or the Pistols or the Damned’s New Rose, it’s got an insane energy that had been so lacking. I would see these bands live, and the odd ones who were brave enough to do Top of the Pops, like Generation X, and the first thing I would say was: “I could fucking do that.”

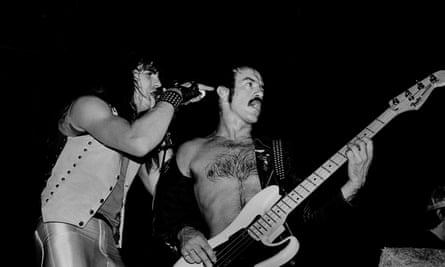

Cronos: My influences were punk and bits of Black Sabbath and Status Quo. When NWOBHM started, you had bands like Iron Maiden and Saxon coming out, but I just saw that as a rehash of Purple and Zeppelin and bands like that. I wanted something different. Plus I had that punk element, which they didn’t have. I had that snot and piss and shit element, which I wanted to put back into metal. I saw more and more bands shoving socks down their pants and putting lipstick on, and I just was disgusted by that, to tell you the truth. Fucking hell, if heavy metal was anything it had to be raw and dangerous and in your face.

Neal Kay (DJ, The Bandwagon Heavy Metal Soundhouse, London): Punk had reared its ugly head, trying to destroy music. But not in my venue. It was outlawed. I had the only heavy metal club in the country. And once [music writer] Geoff Barton came here, it changed everything. He wrote a piece in Sounds called: “A survivor’s report from a heavy metal disco.” It was a double-page spread. Then he took our requests chart and put it in Sounds every week, and things started happening. Bands started sending me demos, and with them some incredibly sad letters – “The industry doesn’t answer us, no one gives a shit. We need help.” I took the best of those bands and opened up the rock circuit.

Joe Elliott: Sounds had a more open-minded editor [Alan Lewis], who allowed Geoff Barton a bigger say in that particular area of the magazine than you would ever get out of NME. That then spread to Kerrang! [launched in 1980] so now we had a glossy that’s focused on the music.

Biff Byford: Tommy Vance and Tony Wilson [who, respectively, presented and produced The Friday Rock Show on Radio 1] were also paramount in the success of the NWOBHM bands. The Friday Rock Show was nationwide and if you got played on there you could guarantee people were listening.

Joe Elliott: Talk about marginalised … shove the rock show out at 10 o’clock on a Friday night when everybody that likes that kind of music isn’t at home. If you’re 18, you’ve just discovered pubs. 9.55, I’m gonna leave. Why? I’ve got five minutes to get home for Tommy Vance. Not happening. So you’re looking at people who were so into music that they’d kill their social life to stay in and listen to Tommy Vance. I’d be one of them.

Cronos: I worked at Impulse Studios and I was screaming to get rock bands in. I was going out to local bars at weekends to see bands who were getting up week after week and playing their arses off. It was awesome. It was all about the love of rock music, and that was a massive attraction.

David Wood (owner Impulse Studios, Wallsend, Tyne and Wear; founder of Neat Records): We didn’t really know what we were up to, and the bands didn’t know what they were doing. I went to the first Venom gig, in a church hall in Wallsend. They had the pyro and smoke machines and set it all off, and for the entire set no one could actually see the band. They were immersed in fog. It was exciting and too damn loud.

Cronos: I never wanted to be an Elton John, singing love songs. He does it so well, but I don’t think I could do that. Same as I don’t think Elton could sing In League With Satan.

Robb Weir: Dave took a chance pressing up 1,000 copies of our record – and we sold them in three days. After that he had 5,000 pressed. They sold and a deal got done, and all of a sudden we were on MCA.

Joe Elliott: We made the Def Leppard EP at Fairview Studios in Hull. It cost £148.50. We budgeted for £150, but I think we took three cassettes less than they expected. We had £1.50 left over, with which we bought fish and chips to share between us in the back of the car. I thrust a single in the hand of John Peel; he nearly shat himself when he saw me jump up on stage at Sheffield University with a copy of it. Then on Monday, I’d just got home from work and my mum answered the phone. She said, “There’s a guy on the phone for you, he says his name is John Peel.” He played it every night that week. All the magazines started taking a bit more notice, then the record companies. It was the best thing ever, and it was totally born out of punk.

Neal Kay: One night two geezers from east London turned up at the Soundhouse. One was Steve Harris. The other might have been Paul Di’Anno. They said they had a band called Iron Maiden and could they get a gig. I was blase and rude: you and a million others! But as soon as I heard their demo ... “Wow, this is the one that’s going to change everything.”

Biff Byford: There were bands from London, the north, the Midlands, the north-east, Scotland, Ireland. It was a big movement.

Brian Tatler: Each band sounded different for that reason. No two bands sounded alike. If you’re an outsider it might all sound the same, but from the inside you could tell in a second which band was which. Diamond Head don’t sound like Saxon and Saxon don’t sound like Girl.

Joe Elliott: Our management looked after Aerosmith and Ted Nugent and AC/DC. They saw England as not being good enough for us. We wanted management who knew what they were doing, and there’s a bigger world out there.

Brian Tatler: We were managed by Reg Fellows, who owned a cardboard box factory, and the mum of Sean Harris, our singer. Peter Mensch gave us the chance to open for AC/DC, to have a look at us. After the first gig he came to our dressing room for a chat. That’s never happened before or since, the headliner’s manager going to the support’s dressing room for a chat. He was looking for talent. But Sean was loyal to his mum and would say: “My mum is the best manager in the world.” We knew he was talented, he was the frontman and he co-wrote all the songs, and we had to keep him happy. Even though in hindsight that was a problem. We didn’t realise until it was too late.

Jody Turner (singer/guitarist, Rock Goddess): Rock Goddess and Girlschool were the only women bands that were around at that point, and people did try to make out that we were mortal enemies. There were a few arseholes, but arsehole men are often arseholes to other men. There were occasions when we were treated differently for being women, but not as much as people would think. But I’m quite a hard-nosed cow. Maybe I just didn’t want to see it.

Biff Byford: We’d bump into other bands in motorway service stations. And we knew a lot of the bands from the north-east and we’d get together for a chat over sausage and chips. There was camaraderie, but it was competitive because everyone wanted to be the next big thing.

Robb Weir: Each band tended to stay in their own manor. Maiden would play around London. Saxon would play Doncaster, Leppard would play Sheffield, and we’d play the north-east. We got a gig down in some club in Sheffield, and the people down there were saying: “You’re from Newcastle? We normally have Def Leppard here.” Well, did you expect us to wear kilts and have three heads? It was regional, then when Geoff Barton wrote about it in Sounds, he took hold of the dandelion that was the start of NWOBHM and he just blew it. It dispersed not just nationwide but worldwide – to bands like Krokus in Switzerland and Accept in Germany. Record companies were waking up to this revolutionary time of new bands playing hard rock.

Joe Elliott: What brought us together is the collective that was available to us: Sounds, Tommy Vance, Top of the Pops, Whistle Test. Maiden were the first band of our time, of that kind of music, to make Top of the Pops. We did it in 1980, but got cut because we did it the same day as the launch of the first space shuttle, which they covered live instead.

Biff Byford: We knew enough to realise it wouldn’t always be like this. We’d just gone through the punk thing. That had been global and massive. And a few of those bands went on, but it didn’t last and people got bored of it.

Tony Wilson (producer, Friday Rock Show): Certainly by late 1982, early 1983, things had taken a distinct change in direction, with more American bands coming through. The early days of thrash are when it starts to change, then hair metal.

Robb Weir: MTV came along, and all the hair metal bands could get on to MTV.

Jody Turner: Metal had to move and change. But bands like Saxon and Priest are still bringing out albums that are so relevant, and still have that NWOBHM flavour.

Brian Tatler: It’s on record that we inspired Metallica. And Maiden’s legacy has been incredible. I don’t know how many kids today would listen to the roots of modern metal, but they’d still pick up on Maiden. But with the internet, it’s all there. Even the very obscure B-sides are there. I’d like to think some kids still listen to it.

Jobcentre Rejects – Ultra Rare NWOBHM 1978-1982 is released on On the Dole Records on 10 May. Diamond Head play Islington Assembly Hall on 12 June and Camp Bestival on 25 July. This Time by Rock Goddess is out now on Bite You to Death Records. The Venom boxset In Nomine Satanas is released on 31 May on Sanctuary. A boxset, Def Leppard – Volume II, is released 21 June on UMe/Virgin.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion