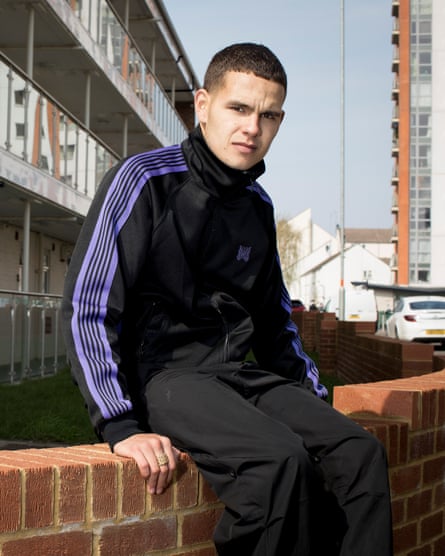

It has just gone midday in Northampton and Slowthai’s day is off to a good, late start. He meets me in his mum’s back garden, wearing a pristine tracksuit and a dreamy grin that turns out to be a permanent fixture. His voice bubbles with mirth, as if he’s constantly remembering something funny. “Fresh out the bath,” he explains. “Fresh like a baby. Sun’s out. Feeling good.”

Tyron Kaymone Frampton goes by Slowthai because he used to slur and mumble, so his friends would call him Slow Ty. These days, he can’t stop talking but it’s too late to change it now. Accompanied by his cousin and manager Lewis and his friend and driver Chad, we head for Abington Park, where he spent a significant portion of his adolescence. Eyes gleaming, hands weaving, Frampton turns a walk in the park on a bright spring day into one long Proustian rush, with an anecdote at every turn. Here’s the hill where he and his mates let off a box of fireworks and ran from the police; there’s the bench where he wrote his 2018 breakthrough single T N Biscuits to cheer himself up after losing his job at Next. His reminiscences are punctuated by lively theories about such diverse topics as squirrels, serial killers and carrots, not all of which withstand close inspection. Lewis smiles indulgently: “Everything Ty says is 50% true.”

Slowthai is Britain’s most compelling new MC. His brand of hip-hop isn’t exactly grime but it is grimy: pungent and abrasive in sound and content, but charming with it. His uproarious, hair-raising take on modern Britain has plenty of signposts – the Streets, the Specials, Dizzee Rascal, Slaves – yet feels blazingly original by dint of his irrepressible personality. There is considerable excitement around his debut album, Nothing Great About Britain, and nobody is more excited than Frampton. Life is, he says, “amazing”.

Frampton may spend most of his time in London with his girlfriend but his home town’s NN postcode is tattooed on his finger and it’s just as indelible in his music. The album cover, on which he poses naked in a set of medieval stocks, was shot on the Spring Boroughs estate, where he lived as a baby. The album title, he says, isn’t quite as damning as it seems. “I love this country but I feel like we’re losing sight of who actually holds the power and what makes us great: it’s the people, the communities, the small places that are forgotten, everyone that’s striving. It’s a question. I should have put a question mark [on it] really, shouldn’t I?”

Frampton is prone to being misunderstood. When he started deploying the union flag during his raucous live shows, some people who didn’t realise he was biracial assumed he was “like EDL, one of them guys”. “The flag is a way of saying I’m proud to be from here but in the same way I could burn it, you know what I mean?” he says cheerfully. “It don’t mean nothing. The real thing is the connection we all have.” Similarly ambiguous was the name of his recent Brexit Bandit tour. He voted remain in a leave town but, he says, “On the album, it’s not like I pick a side. I just give my perspective on how my life was and I hope people who have had a similar sort of thing can relate to it.”

His opinion of the monarchy, at least, is crystal clear. On the album’s title track, he calls the Queen a word that the Queen is not accustomed to hearing. “My real dad was like: ‘Why would you ever call the Queen that?’” Frampton says, laughing. “But I didn’t ever say I wanted a queen. The only queen I know is my mum. It’s a primitive thing, kings and queens.”

There go your chances of an MBE. “I don’t really want one,” he beams, his teeth resembling a chessboard. “I get knighted in the school of life. Like Braveheart.”

Frampton idolises his mum, Gaynor, who is half Bajan. A few years ago, he had the words “SORRY MUM” tattooed on his chest after asking himself: “What have I said the most in my life?” When he played her the autobiographical album closer Northampton’s Child (“You’re the strongest person I know / Made us happy even when you felt down”), it was the first time he had ever seen her cry. “I think she was surprised I could remember some of the things and tell the story in the way that I did,” he says.

There is a lot to tell as we walk through the park, past knots of holidaying schoolchildren. By the time she was 24 – which is Frampton’s age now – Gaynor was married with three children, living on the Lings estate. Her youngest son Michael, who had muscular dystrophy, died just after his first birthday, throwing eight-year-old Ty into a tailspin. His Irish stepdad, who might kindly be described as a maverick entrepreneur, thought his son’s death was divine punishment for his misdeeds and became a Seventh-day Adventist, taking Ty with him to church. Frampton also had anger-management sessions and discovered the therapeutic power of hip-hop via a bootleg VHS of 8 Mile.

In the end, though, it was a simple ritual that helped him to move on. “I never felt like I said something to my brother so I wrote a letter to him and put it on a balloon,” he says, gazing up into the deep blue sky. “When I let the balloon go it was like: ‘Yeah, you got my message.’ And from that point I wasn’t so quick to be aggressive. I let go of feeling that way.”

When Frampton was 13, his family moved out of Lings, leaving his friends behind. “People don’t like you to leave,” he says sadly. “They don’t want you to go anywhere else.” He shows me the tree opposite Abington Park Museum where he carved his name with a key (it’s still there) and used to get screamingly drunk on Lambrini. Most of his stories about this period end with him being chased by the police and/or an angry shopkeeper (“Just being a yob, I suppose.”).

He points to the spots where he hung out with the punks, students and skate kids who introduced him to bands such as Radiohead – “Obviously, Creep was the one I related to” – and rescued him from what he calls “toxic masculinity”. “When you’re with the boys on the estate, it’s all about who’s the roughest, how you dress, what you’ve got, how many girls, all stupid shit. Seeing people who don’t care about any of that was refreshing.” If he hadn’t studied music at Northampton College, he says, “I’d still probably be an ignorant idiot, sitting there hating stuff.”

Lewis calls a cab and we head to The Vintage Retreat, a tea room on the edge of Spring Boroughs. Frampton is delighted to see that the cab’s licence number is 47, his lucky number. “I take it as me being where I’m meant to be,” he says serenely. “Today’s a good day.”

At the tea room, Frampton orders a spicy chicken sandwich and a cappuccino and picks up his story in 2012, when he made his first EP, BLU, meaning Better Less Usual. “Some things are better unusual,” he explains. “That’s when I figured out I can’t fit because my thing is rough. It’s not pitch perfect, it’s not musically correct, it’s just my feelings.”

Back then, most of his musical heroes were local MCs. “I only wanted to make music for Northampton. If everyone here knows me, why do I need anywhere else?” That’s why he called himself Slowthai, because everybody knew Slow Ty, but nobody was listening. For a few years, he drifted between minimum-wage jobs and a more lucrative sideline that he shiftily refers to as “other stuff”, until his 2016 track Jiggle (“You get robbed like Lidl”) caught the industry’s attention in London and New York. Eventually, Northampton noticed him, too.

Frampton is still enjoying his honeymoon period in the music industry. Every show abroad – New York, South Africa, Dubai – is an eye-opener. Recently, he met two of his heroes: Mike Skinner and Damon Albarn, who is apparently “mad in touch with his inner child”. Does he currently have anything to complain about? “I think I do but then I have to slap myself.”

Frampton is so giddy with ideas that he barely touches his sandwich. He thinks visually, promoting the album with billboards featuring sobering statistics about Britain in 2019, and making videos in which he acts out scenes from Trainspotting and A Clockwork Orange. Next he wants to write a comic book, like his Northampton neighbour Alan Moore, and make an album called Life’s a Sitcom, with a character for each song. “One day I’d like it so you could lick the album and taste the sweat,” he says. “I want it to be so you can smell, you can taste, you can touch, you can see, you can hear. I want to build worlds.” His enthusiasm is so contagious that I almost think a sweat-flavoured album is a good idea. “What’s the word where you can do everything?” he says, rolling on. Polymath? “Polymath! I want to have a go at everything I enjoy, everything I love, everything I’ve ever got lost in or seen as part of documenting history. I want to be part of history.”

Lest anyone think that he’s turning into the East Midlands Kanye, Frampton would also like some people to tell him his album stinks. “I want some people to come at me and then I can fight that shit and go harder,” he says. “It’s my motivation. Everyone’s like: ‘Yes, yes!’ And I’m like: ‘No, no!” He laughs: “Tell me something’s wrong, man.”

When he plays live, Frampton mounts mirrors on the stage so that his fans can see, and celebrate, themselves rather than him. While it is hard to ignore a man who tends to end up crowdsurfing in his boxer shorts, this idea of allowing people to feel seen is a recurring theme. Much of the Brexit vote, he says, came from “the places we forgot to look at”. His album is about the people in the pubs, parks, shops and estates who don’t normally get written about. “I just want to connect with the people it matters to,” he says. “Build my community of the lost kids who felt the same as me, that didn’t feel like they could fit into anything.”

Frampton remembers feeling as if nobody except his mum cared where he ended up. He remembers acting out the stereotype that others imposed on him: the no-hoper, the “little shit”. By talking and rapping about that grim expectation, he wants to dismantle it.

“Because I made a lot of mistakes growing up and did some things that I don’t particularly like, this is my way of showing that don’t determine me as a person for ever,” he says. “Everyone has that stereotype when you’re a bad kid: you’re going to go to jail and end up with a kid at a young age. Well, I ain’t in jail and I ain’t got a kid and my family’s proud of me.”

He leans back in his chair and laughs softly at his own good fortune. “I’m doing pretty well.”

Nothing Great About Britain is released on Friday 17 May