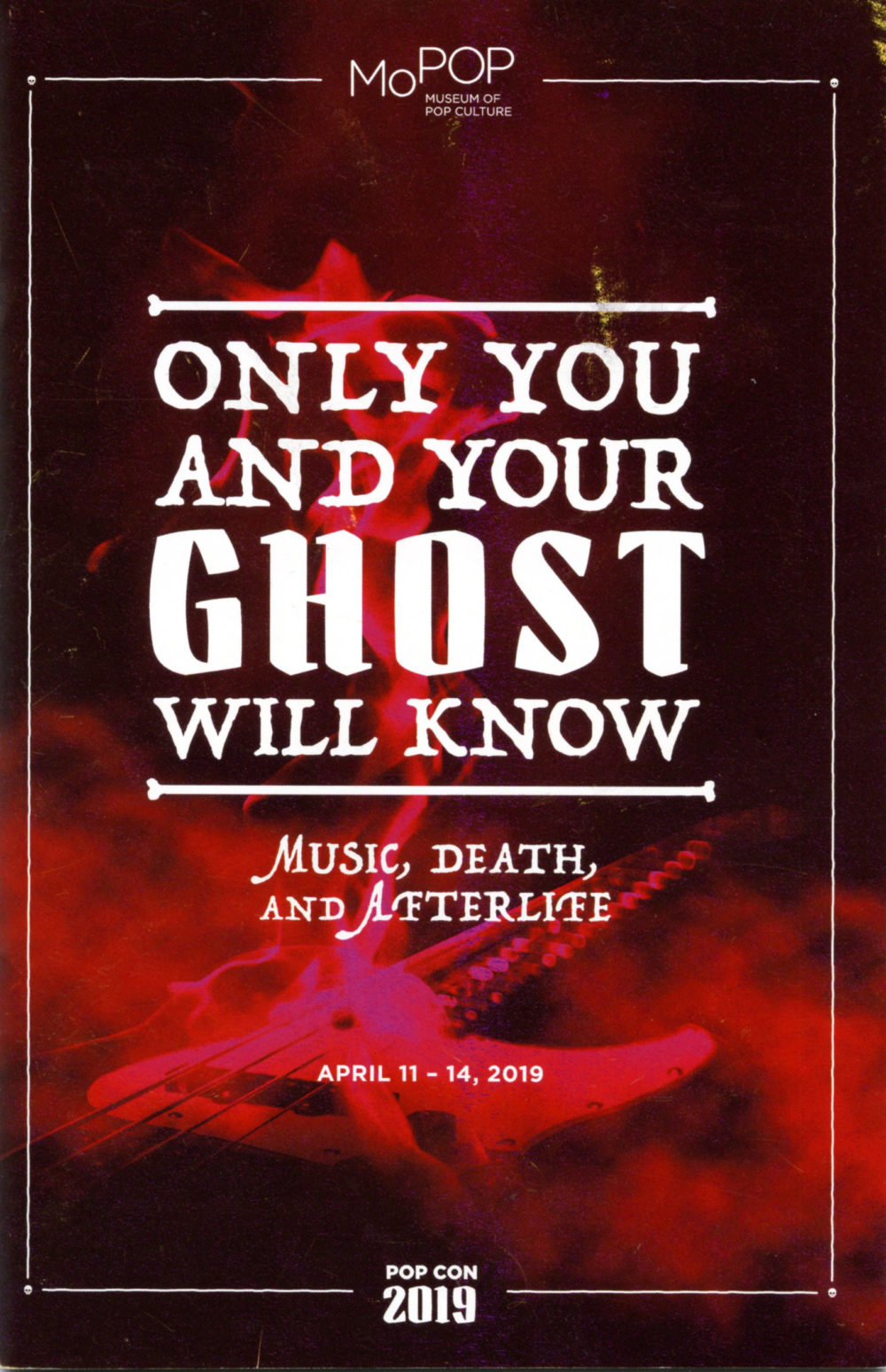

For the past 17 years Seattle’s Museum of Popular Culture (formerly the Experience Music Project) has hosted a pop music conference for writers and scholars of popular music. Each year has a theme, and the 2019 edition cut particularly deep: Only You and Your Ghost Will Know: Music, Death and Afterlife. Over four rich days, there were meditations on fallen musical heroes, memorials to friends, tales of archives lost and found, of bands trying to replace a deceased mate, and of music as a way of remembering and even connecting with ancestors. Perhaps the most poignant and pervasive theme was how we remember the greats when they are gone and only the work remains.

This year, the African music community has lost an unusual number of icons and beloved fellows. In just three months since Zimbabwean legend Oliver Mtukudzi passed away at 66, we now note the deaths of South African jazz diva Dorothy Masuka (1935-Feb. 23, 2019); Ghanaian ethnomusicologist/author/composer Joseph Hanson Kwabena Nketia (1921-March 13, 2019); Congolese music guitarist/composer/bandleader Simaro Massiya Lutumba Ndomanueno (1938-March 30, 2019); charismatic saxophonist for the immortal Orchestra Baobab, Issa Cissokho (? – March 25, 2019); and pioneering vocalist of the Two-Tone movement and co-founder of the English Beat, Roger Charlery, A.K.A. Ranking Roger (Feb. 21 1963-March 28, 2019).

Memorializing such a diversely talented set of individuals is an overwhelming task, one that will extend far into the future in many forums. But here, a few brief comments are in order.

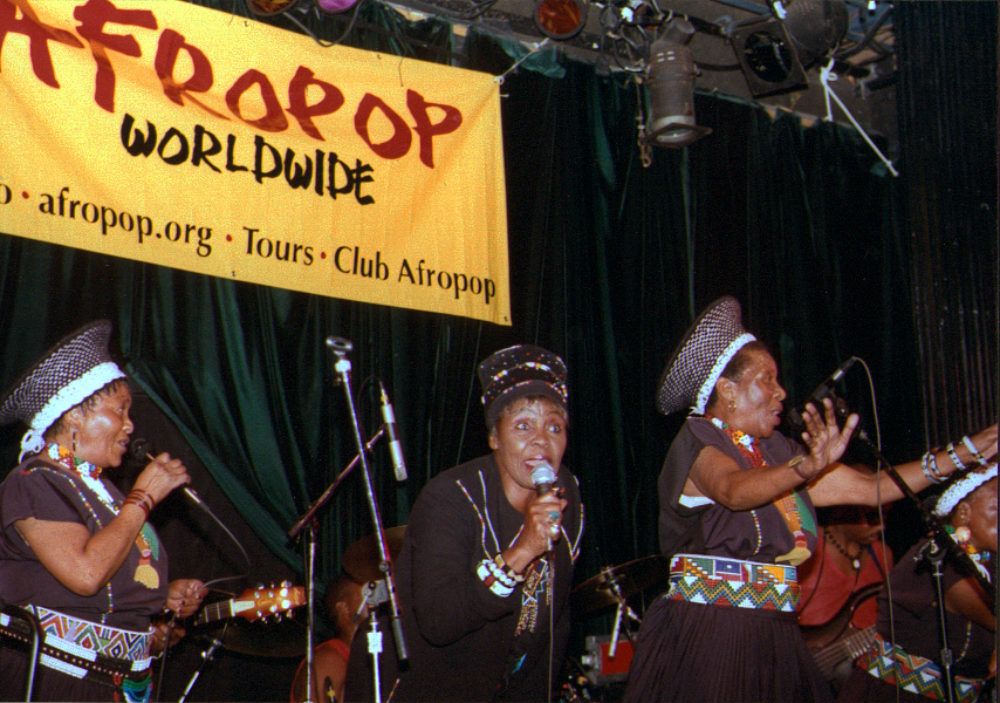

Dorothy Masuka (sometimes Masuku) was born in Bulawayo (Zimbabwe) to a Zulu mother and a Zambian father. By 19 she was touring South Africa, and she went on to become one of the most consequential singers and composers in southern Africa. Her 1961 praise song to Patrice Lumumba forced her into exile in Zambia, and from there, she became an international player, enlivening stages all over the world, right up to her final U.S. performance alongside Abdullah Ibrahim and Ekaya at the Town Hall in New York in April 2017.

Afropop has a special connection with Dorothy, as she was part of perhaps our most memorable live event: Let Freedom Sing at the Bottom Line in New York in April 2002, the evening in which Dorothy was inducted into the Afropop Hall of Fame. That remarkable night featured performances by Bonnie Raitt and her band, and Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited, but the highlight of the night was Dorothy in a set with mbaqanga legends the Mahotella Queens. Dorothy is best remembered as a jazz singer, a composer of serious songs whose own set often included a Yiddish lullaby taught to her by a female Jewish mentor. But none of that stopped her from shimmying and wailing along with the fabulous Mahotella Queens. It was one for the history books, and no one who was there will ever forget it.

During that visit, I interviewed Dorothy and she had plenty to say, but when my questions went deep, she declined, noting, “I’m saving that for my autobiography.” We can only hope that she did put some of her world-wandering life down on paper, and that the biographic film she was working on with Mfundi Vundla will someday see the light of day. For more on Dorothy, read Afropop’s 1990s-era bio of the legend in her prime.

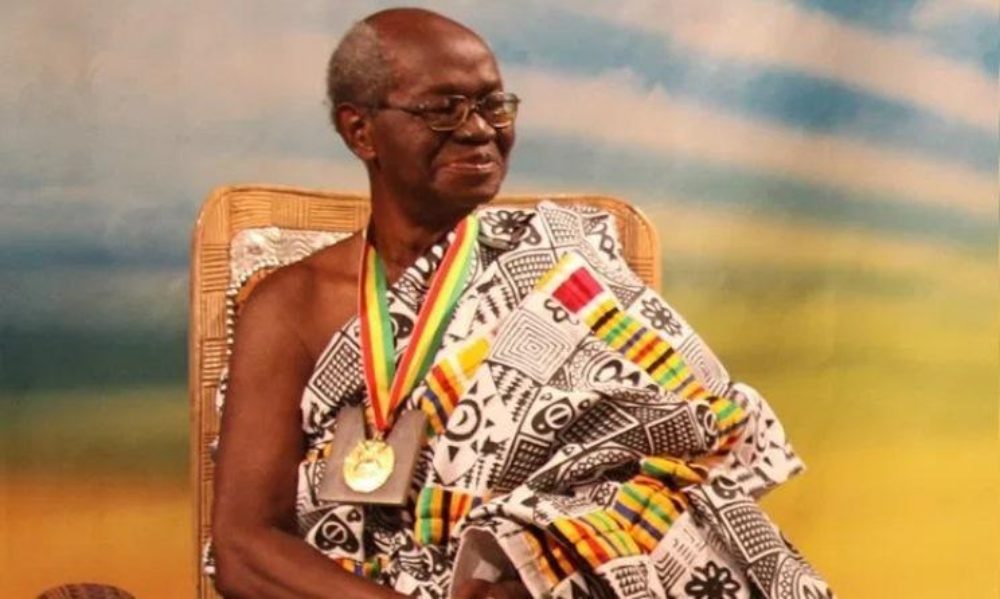

With more than 200 publications and 80 compositions to his credit, Professor Kwabena Nketia is rightly heralded as “the most published and best known authority on African music and aesthetics in the world.” The field of ethnomusicology barely existed when Nketia began publishing books in 1963. His 1974 book The Music of Africa laid the foundation for a flood of scholarship that continues to the present. His formulation of how to understand African rhythms upended existing scholarship and remains gospel today. Nketia’s contributions to music and scholarship earned him numerous awards including the Order of the Star of Ghana. He will be honored with a state funeral in Accra on May 4.

On a personal note, I take special pride that my 2015 book Lion Songs: Thomas Mapfumo and the Music That Made Zimbabwe was awarded the Kwabena Nketia Book Prize from the Society of Ethnomusicology’s Africa section. It’s an honor I’ll spend the rest of my days living up to.

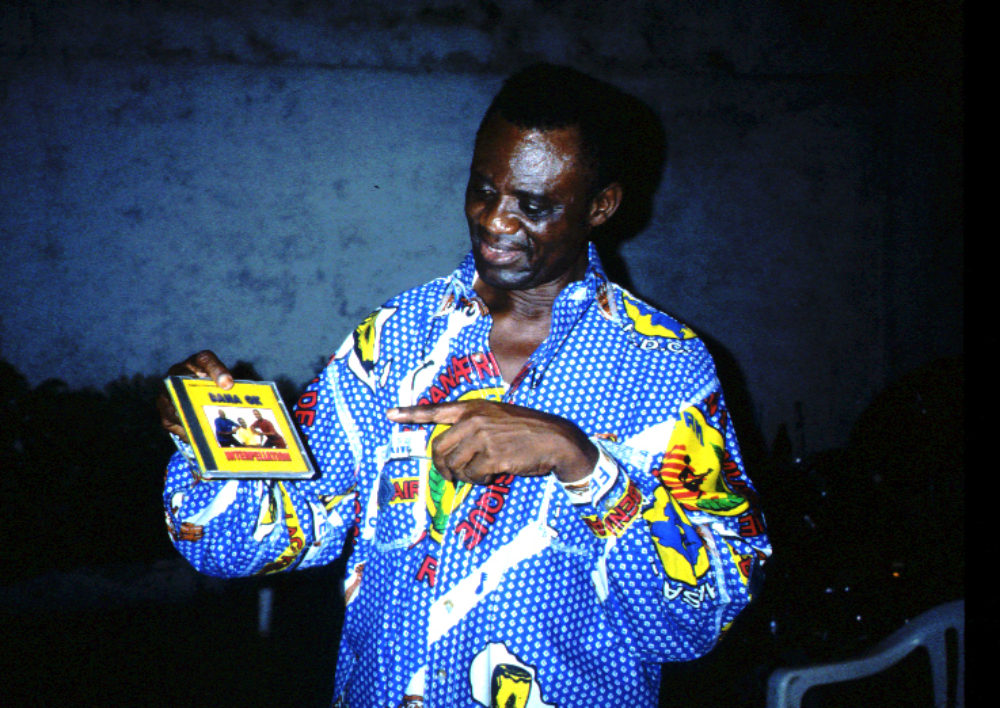

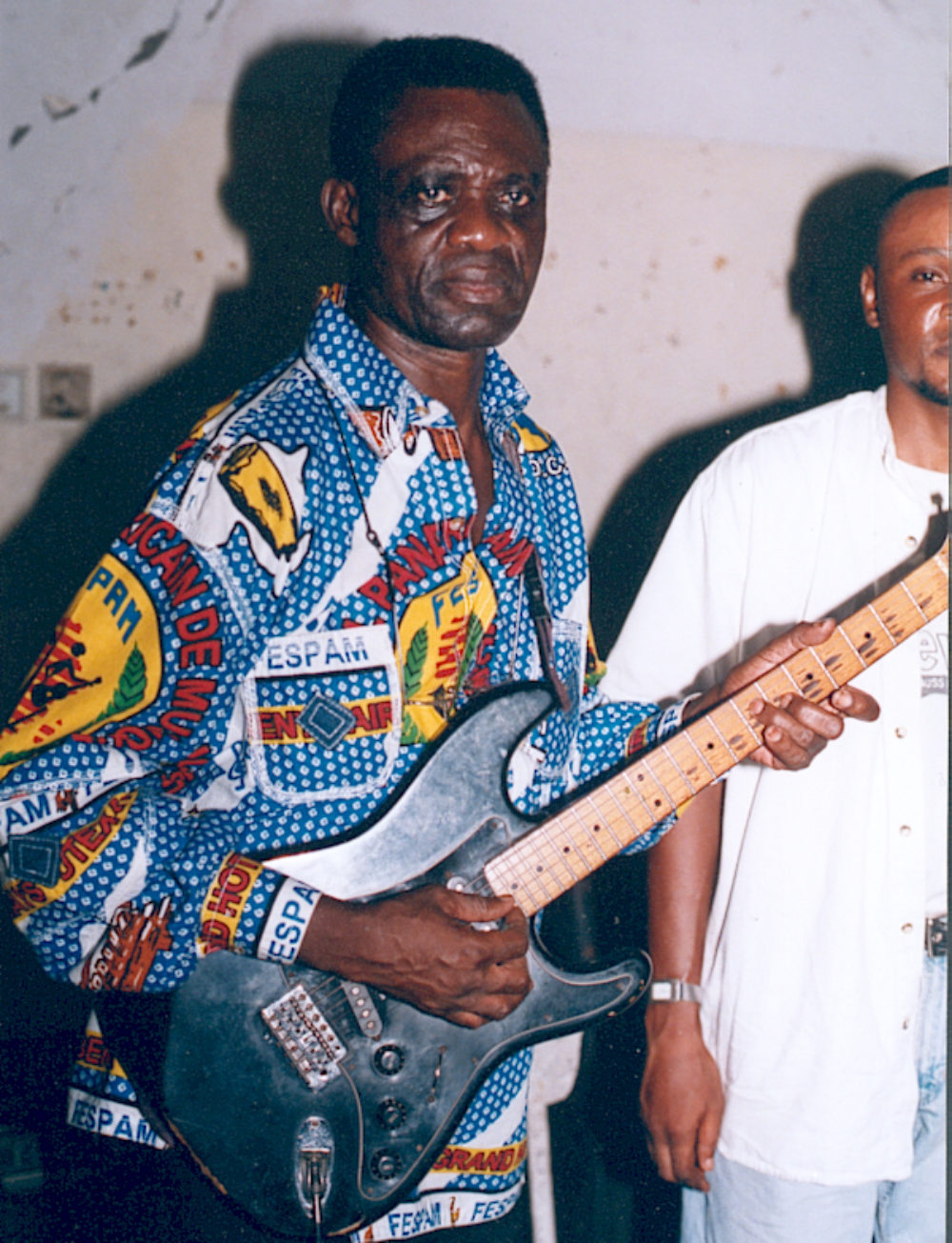

Simaro Lutumba first rose to prominence as guitarist, composer and eventually vice president of T.P.O.K. Jazz, the towering Congolese band that Franco Luambo Makiadi led for 35 years. Simaro was at Franco’s side through the band’s most glorious years, so it was fitting that after Franco died in 1989, Simaro took charge of the musicians. But in the fractious years that followed, the old band dissolved, and in 1994, Simaro began a new career as the leader of Bana OK, which went on to produce its own catalog of wonderful recordings. Simaro was featured numerous times on Afropop Worldwide, although we interviewed him just once in Kinshasa in 2002.

Issa Cissokho was born a Malian griot, but once he picked up the tenor saxophone and joined forces with Orchestra Baobab in 1972, he became a flamboyant Afro-jazzman based in Dakar. Over the years, he performed and recorded with Youssou N’Dour and with the Afro-Salseros de Senegal in Cuba in 2001. When Orchestra Baobab launched its remarkable comeback in 2002, Cissokho wowed audiences worldwide with his soulful elegance and irrepressible stage antics, which won him as much attention and acclaim as the legendary band’s fantastic vocalists.

As for Ranking Roger, what can I say? I fell in love with the English Beat in 1982 when I saw them play in the University of Oregon gymnasium. I had little idea what to expect, but I was never the same. An ardent reggae fan at the time, I found Roger’s pepped-up take on ska animation, his rollicking, rowdy melodies and explosive stage presence nothing short of a revelation. That band didn’t last long, and Roger continued to perform with his own bands thereafter, but the world will likely remember him best for those English Beat albums and performances, which ushered in a new era in popular dance music.

Obviously these brief remembrances barely scratch the surface of these great lives now ended. But as was so evident in the Seattle séance just passed, remembering in all forms is important, and it’s collective, something we can and must share. These five now join the ancestors, but their legacies will shape the living long after we are all gone.

Related Articles