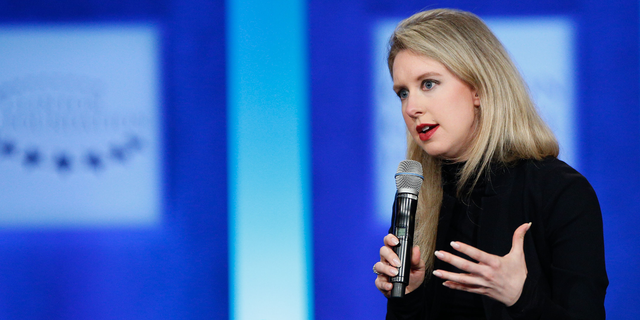

None of my friends can stop Googling Elizabeth Holmes. I can't stop Googling Elizabeth Holmes. On Twitter, dozens of prominent women have confessed they're obsessed with her, too, with the writer Rachel Syme effectively speaking for us all when she admitted, "I will read everything/ watch everything/ listen to every podcast/ eavesdrop on every conversation in every coffee shop about how those little blood amulets were made of cheap glass and jazz hands." Or:

We're not hurting for content, let's say. Holmes has been the subject of endless Vanity Fair features, as well as John Carreyrou's 2018 book Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup, with some 500,000 copies sold. Gary Sanchez Productions' Adam McKay is adapting the book into a movie, with Vanessa Taylor writing the script and Jennifer Lawrence set to star. There's also a Holmes-focused podcast, The Dropout, plus the Alex Gibney-directed documentary, The Inventor: Out For Blood in Silicon Valley, which debuts tonight on HBO and is sure to continue to churn the chatter around our favorite fallen scientist — ahem, "scientist." Not even Holmes' split ends have escaped analysis.

Yet, for all the media coverage, we still can't get enough. Which begs the question: Why has Holmes emerged as such a compelling figure in an era already rife with con artists, replete with grifters? Between former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort, Fyre Festival fraudster Billy McFarland, and the faux-German, faux-heiress Anna Delvey — whose con is set to receive the Shonda Rhimes treatment in a Netflix series for which I cannot wait — well, to stand out from this pack takes some doing.

In part, it's because Holmes claimed to be on a modern-day mission of mercy. She originally rose to prominence as the dazzling young founder of Theranos, a medical startup which claimed to have proprietary technology capable of running a battery of tests using only a single drop of blood — technology that would not only revolutionize diagnosis of a laundry list of illness, but would also give billions of poor people access to the most basic diagnostic tool there is. Theranos eventually took in around $700 million of venture capital. At its peak, the company's valuation reached $9 billion, and because Holmes held half the stock, she saw her net worth top $4 billion. Forbes crowned her as the world's youngest "woman billionaire." Then things got interesting.

Beginning in October of 2015, Carreyrou published a devastating series of exposés in the Wall Street Journal. It turns out the much-vaunted Theranos tech was bogus, its test results inaccurate, and the company's claims largely fictional. Holmes plummeted from grace.

Currently, Holmes is facing up to 20 years in prison for wire fraud. But the criminal charges are only a tiny drop of the story. Carreyrou's book reads in part like a particularly appalling Glassdoor review, dwelling over the ways Holmes and her cronies bullied and manipulated their employees: along with her COO (and then boyfriend), Sunny Balwani, she berated employees, sent threatening emails, promised to sue people, and pressured the scientists and lab techs to help mislead authorities who came to inspect the Theranos lab, and abruptly fired those who expressed concerns about the faulty tech. One Theranos scientist, said by his wife to be depressed and afraid of losing his job, committed suicide in 2013.

There's also the small matter of the patients who received incorrect blood-test results, which could lead to a myriad of fallouts such as incorrect diagnoses, initiation of incorrect treatment, or failures to begin necessary treatment. Nine plaintiffs are representing the alleged victims in a class-action lawsuit, including a man who claims he could have avoided a heart attack by not using the Theranos test. Meanwhile Holmes was partying at Burning Man during Theranos's final days and, even now, she's yet to express remorse. In fact, according to some reports, she sees herself as the victim. As a former Theranos executive told Vanity Fair, "She blames John Carreyrou," as well as the lawyers David Boies and Heather King, who represented her during the period of the initial Wall Street Journal coverage.

Holmes may not be a genius inventor, but she's certainly a genius. She used to depict herself as a Palo Alto Marie Curie. Now she looks more like an IRL Lady Macbeth, all bloody hands, ruthless ambition, and fake baritone. It feels so 2019, as if Holmes had somehow trapped the zeitgeist in one of her "nanotainers." As Megan Garber recently wrote in The Atlantic, at this moment in America, when long-cherished celebrities are criminally securing their kids places at top-tier universities, scams "are atmospheric. They are miasmic, hovering in us and around us, their toxins trapped in human lungs and expelled into the warming air." At the same time, Holmes' story draws on the stuff of lasting drama — out, damned drop! That’s what makes the public spectacle of her downfall so spectacularly compelling.

As an alleged criminal, Holmes is far more fascinating to me than she ever was as a Silicon Valley swaggerer. Any TED talker can blab about changing the world. But Holmes appears to have done it in full knowledge that her claims were lies. I feel like a goober when I have to give a PowerPoint presentation, and interviewing people who are smarter and more successful than I am causes me so much anxiety it could recharge a Tesla.

Like many women, I experience chronic, low-grade imposter syndrome, with the occasional intense flare-up. Whereas Holmes, an actual (alleged) fraud, seems immune to imposter syndrome, in the same way sharks are supposedly immune to cancer. What if Holmes' ultimate usefulness to science is in her immunity to self-doubt, not in her snake-oil blood tests? If she could somehow isolate that freak quality and market her immunity, she'd probably become a billionaire again. I might be first in line to buy the moon-dust. I look at her career of (alleged!) high-flying, high-stakes conning — activities for which I lack the stomach, the nerve, maybe the sociopathy — and it's like that moment in When Harry Met Sally. Part of me wants to say, "I'll have what she's having." If I had that kind of blind faith in myself, I have to think my life would be utterly different. If more women had that kind of faith in themselves, the whole world might be utterly different. Consider what we might achieve in science, in the arts, in politics, if we all pushed forward unafraid of judgment, criticism, mores, limits. What if were possible to keep the DGAF attitude but lose the fraud?

In a sense, I admire the chutzpah of Elizabeth Holmes, and it's not because I don't realize she's an alleged criminal. Aren't we all transfixed by that unblinking self-belief? She's the millennial who took the "you can be anything you want to be" ethos that so many of us were raised with, and ran with it to its logical, if quite likely illegal, conclusion. She makes me want to use the word "uber," because she's a kind of millennial American Übermensch. I mean, holy crap. The sheer balls of it.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY