The Family Vice

Some sons bond with their dads over football games. Tom Junod bonded with his over betting them.

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's January issue. Subscribe today!

It wasn't a secret.

It was illegal, and it ruined him. But we could talk about it. It was, in fact, about the only thing in his life that wasn't secret, and for that I'll always be grateful to the great god of gambling, which despite its hunger and bloody fangs gave us point spreads and football Sundays together.

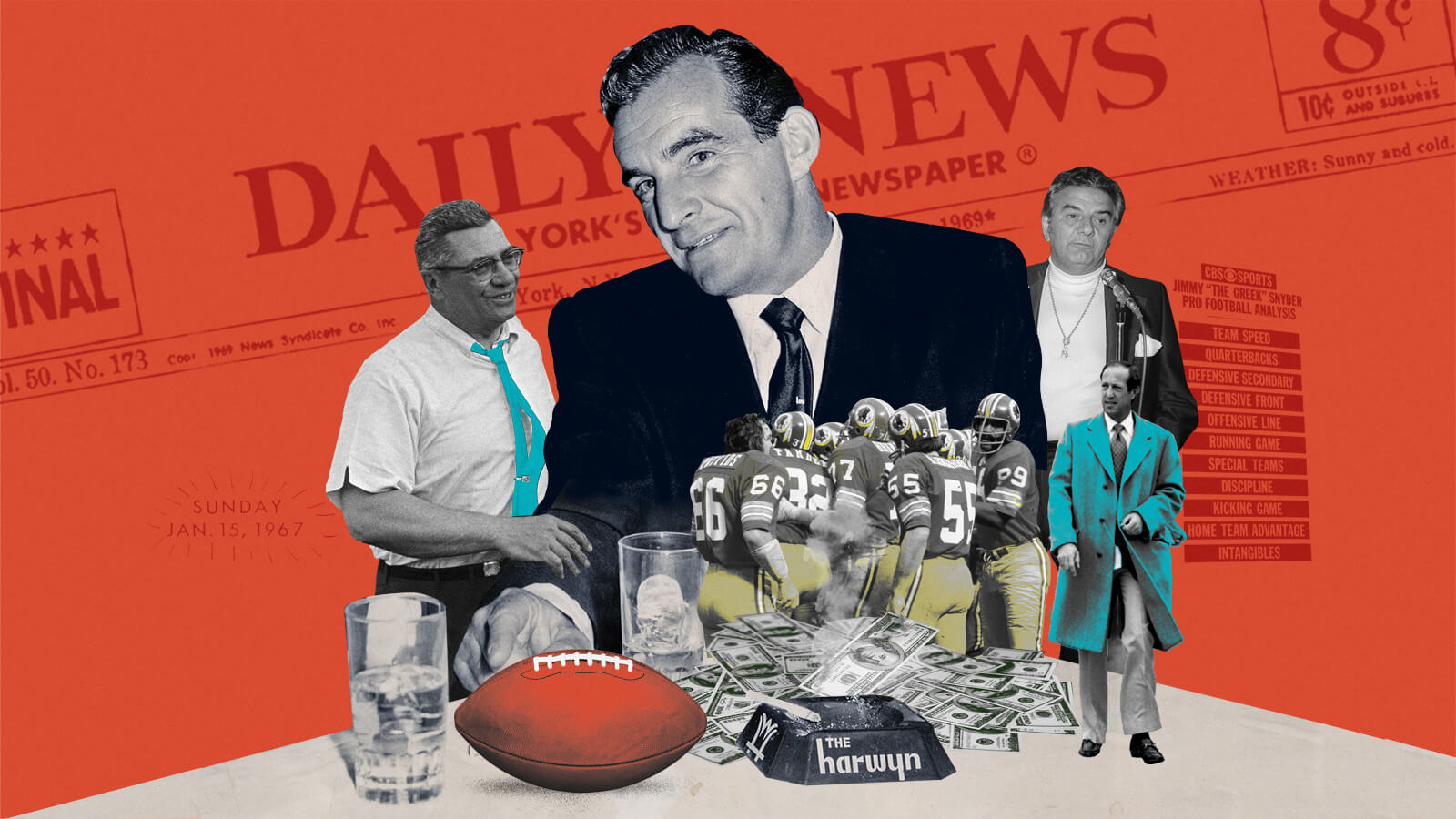

Everybody thought Lou Junod was a gangster. He not only looked the part, with his pinkie ring and French cuffs and blue dress shirts white at the collar, he played it, cultivating an air of danger. He had beautiful manners and always strove to be a gentleman, the striving itself a part of his charm. But there was something feral about him behind the civility, the elaborate coded masculinity and even more elaborate actorly diction. He chased down men when they cut him off in traffic and got into fistfights well into his 70s, his anger an eclipse you couldn't help but look at even though you knew it would strike you blind. He had an underworld glamour, even to his own children, and a reputation. People figured he had "connections," and he did -- his connections called our house, like old friends. But they weren't friends. They were bookies, and they had him by the balls.

He placed his first bet on the first Super Bowl, Chiefs-Packers 1967. That was also the first football game I ever watched, because my uncle George was married to Vince Lombardi's sister. Who the hell knows why you fall in love, but I can tell you that several love stories began that day: between America and the NFL, between my father and gambling, between me and football, and between me and my father.

I was 8 years old at the time, alone in the house because my brother and sister had just gone off to college. I was afraid of him until football. He scared me often to tears, and football gave me a way of talking to him without crying. And it gave him a way of talking to me, well, without making me cry. I dedicated myself to football in an effort to reconcile myself to him, and to reconcile him to the rest of my family. That he lost tens of thousands of dollars in the process didn't really matter as much to me as my role in trying to help him win.

I knew it was against the law. I also understood that the bookies who called our house were committing crimes. Did that make them criminals? Did that make my father a criminal? Who was the crime against? It couldn't have been against the NFL, because the NFL was in on it -- that's what my father said. Every Monday morning, the newspaper published the "Latest Line," and it kept publishing it throughout the week. How bad could any of it be if the line was in the paper like stocks and bonds?

The "underworld" was supposed to stand for everything that was wrong with America. The NFL was supposed to stand for everything that was right. But they met on Sundays, after church or, in my father's case, instead of church. They met in our house, when the phones started ringing. Hell, they met on television, when Jimmy the Greek told viewers the teams he "liked" before the games. "Dad, who's Jimmy the Greek?" "He's a tout." "Dad, what's a tout?" "A tout's a guy who hangs around the racetrack and sells tips." "Does he know anything?" "He doesn't know any more than you and me."

And that was the thing: Nobody knew, not even the Jimmy the Greek. Everything was out in the open, but everybody was kept in the dark. Was betting on games quasi-legal or quasi-illegal? Did the NFL exist to give people an excuse to bet, or did betting exist to give people an excuse to watch the NFL? It was never even clear who ran the whole operation. People thought my father was a gangster; I thought NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle was the gangster because he wore the same kind of shirts my father did and sported the same varnished tan. But who was behind Rozelle? Who set the line? Who was the gangster behind the gangster?

I was my father's tout. For 10 years, from the time I first watched "Uncle Vince" coach the Packers to the time I graduated high school, that was my employment, with a workweek that started when the paperboy dropped the Daily News in our mailbox on Monday mornings. We lived on Long Island, and everybody else on our block subscribed to the Long Island Press or Newsday. But my father "liked the sports section in the News," which meant that he liked the attention it gave to the needs of gamblers. I would come to the kitchen table for breakfast and he would hand me a stub of a pencil and open the paper before me to the Latest Line. The racetrack listings would already be marked up, subject to my father's blocky exegesis. But the little box of agate type, with its strange cuneiform flourishes -- "home team in CAPS" -- was all mine, and I would stare at it like a scholar until my father asked, "Who do you like?"

It should have been an easy question. After all, my father called me a "walking encyclopedia" when it came to football, because all I did was study my Street & Smith's annuals, my Pro Football Weekly and the cheaply printed tip sheets he bought at dear price because they "guaranteed" winners. There was nothing I didn't know, at least statistically, about most players and teams. But it was not an easy question, given all that hinged on the answer. Who did I like? He wasn't asking about my allegiances, except perhaps my allegiances to him. He was betting $1,000 a week and asking me to beat a point spread whose shifts mocked my certainties and careful preparations. More than that, he was making a connection through his "connections."

"Dad, I like the Raiders against the Jets minus-9."

"It's 10 and a half."

"But the paper says 9!"

"So bet the paper," he'd say, and we'd laugh.

My father was a man of many vices and an untold number of secrets. But his gambling was the one secret in which we could all participate. Illustration by Max-o-matic

The calls came to my parents' bedroom. There was a yellow phone on the nightstand with a little toggle switch that gave it two numbers. When the switch was horizontal, the phone belonged to us -- calls came in and went out on "our" number, the one listed in the phone book. When the switch was vertical, the phone belonged to my father, a conduit to his secret world, with a number I don't know to this day. It was his "business phone," he said, and there were two kinds of calls announced by its distinctive chirping ring. The first were from his "buyers," most of whom were women, and these he answered with the door closed, speaking in low, soothing tones indecipherable to me or to my mother. The second were from bookies, mysterious in their own way but carried out with the door open.

My father sold handbags and made a lot of money doing so. But the bookies sold opportunity, and they were relentless. They called all week long, and on Saturdays and Sundays they called all day long, proffering exotic parlays and teasers. My father spoke to them in code. When he told the bookies "20 dollars on the Dolphins," he was betting $200. When he said "a hundred dollars," he was betting $1,000. And when, on Super Bowl Sundays, he placed a bet, sotto voce, for "a thousand dollars," well, he was risking something unimaginable.

My mother, Fran, listened as intently as I did, from the kitchen and sometimes from the flocked hallway right outside the bedroom door. She fretted, wringing her hands the way she did when she sat as a passenger in the car and my father, often in anger, started speeding. "Oh, I hate those parlays," she'd say. "I hate those teasers." But ultimately she had no choice but to include herself in my father's life as a player, having been excluded from his other life as ... well, a player. My father was a man of many vices and an untold number of secrets. But his gambling was the one secret in which we could all participate.

It was the family vice.

I watched every Super Bowl from I to XIV with my parents. We saw many games now considered historic and witnessed the transformation of Super Bowl Sunday into a national civic holiday. But what I remember, what I can't forget, was the losing. The impossible victory that Broadway Joe guaranteed for the Jets in Super Bowl III? My father had the Colts minus-18. The AFL's last stand as an independent entity in Super Bowl IV, in which Hank Stram's Chiefs portended the NFL's glorious future? My father took the Vikings and laid 17. He bet the Dolphins when they lost to the Cowboys and the Redskins when they lost to the Dolphins, enamored with George Allen's "Over the Hill Gang." He could never win a game that involved the Cowboys, whether he bet with them or against them. He liked the Steelers, but he bet against them when they played the Rams in Super Bowl XIV, because Vince Ferragamo looked like a movie star. My father was, in fact, an inept gambler, but he never blamed me for his losses, at least not out loud, and I never rooted for any team but the teams on which he'd put money. So we learned to lose together.

Which is not to say that we lost alone. My parents threw an annual Super Bowl party, to which they invited friends who had never placed a bet. It was intended as a celebration, but it was a strange ritual, because the triumphalism on the television screen was matched only by the desperation my father displayed from the coin toss to the last tick of the game clock. Our guests didn't know how much he was betting, but they saw his expertly tanned skin go sallow when things didn't go his way, and things tended not to go his way from the outset -- "lose the toss, lose the game; lose the toss, lose the game," he'd repeat, waving his hands in disgust and fetching himself a drink. They also saw my mother trying to placate the gods of chance by hexing players with what she called "giving them the horns." With her pinkie and forefinger extended, she'd put the horns on placekickers especially, and when they missed, she'd cackle in triumph: "See? See? I put the horns on him!" Or more precisely, since she'd lived all her life in Brooklyn or on Long Island: the "hawns."

His friends loved and sometimes feared my father, but when they came to our Super Bowl parties, they occasionally exchanged glances that suggested they feared for him -- and for my mother. And yet what they could not have known is that in the end, gambling is what kept my parents together. It wasn't simply that they both loved it and went to the track and later to Atlantic City as often as they could. It was that gambling provided them the only place where they complemented each other, and their passions, such as they were, existed in perfect balance. My father bet long shots, my mother favorites; my father played poker and blackjack, my mother the slot machines; my father believed that he was cursed and my mother believed that she had the power to curse him. And when my father, perhaps during one of those ill-fated Super Bowls, responded to a disastrous pass-interference call by putting his fist through the door to our den, she refused to have it fixed. The hole stayed in the door for years, a mysterious mandala, until the day they finally had to move out of the house.

My father was an inept gambler, and I never rooted for any team but the teams on which he'd put money. So we learned to lose together. Illustration by Max-o-matic

The first bookie I ever met ran a candy store in Bellmore, Long Island. He was a cigar stub of a man, Jack Ruby without the .38 special. He exuded crookedness but not danger -- the kind of leg breaker who signed the cast -- and my father used to visit him and drink coffee at the counter. They would kibitz and let me look at Playboy. He once got my brother a job as a bouncer.

The second bookie was much more professional, which is not necessarily a desirable quality in bookies. Charlie was trim and dapper, wore suits, and his tanned face shone as if he went to the barbershop for his shaves. He exuded danger but not crookedness. He was courteous and solicitous and generous, setting me up with tickets for concerts and football games and sending a check for my wedding. He worked for what my father called "the Syndicate," perhaps out of concern that "the Mafia" would scare me and my mother. My father went to him because other bookies couldn't handle the sums he had begun to wager.

Charlie was also the last bookie my father ever had, because every so often they had differences not of opinion but of fact -- because every so often he would tell my father that he hadn't bet a game my father thought he'd won or that he lost a game he thought he hadn't bet. They argued, and Charlie would win. Charlie always won. What was my father going to do -- show him the notes he made at the breakfast table with his stubby pencil? My father had to pay him no matter what -- no matter what -- a requirement made clear when he visited my father's office and my brother asked: "What happens if someone doesn't pay?" Charlie's answer was unsmiling and definitive. "He wouldn't want to do that," he said, and my father never did. But I believe that for the first time he had to borrow money to pay his gambling debts -- and that for the first time he got scared.

Two years after my wedding, my parents sold their house on Long Island and moved down to Florida. The house was the only asset they had left, and my father had to live the rest of his life on the proceeds of the sale, including investments. He didn't find a new bookie in his new home. He didn't go looking because he didn't, as he explained to me, "have the money." And then he stopped watching football altogether, because as it turned out, he wasn't really a football fan at all. He was just a fan of betting.

Last May, the Supreme Court ruled that the federal law prohibiting sports betting was unconstitutional and thereby left the question of betting's legality to the states. It is both an eventuality and an inevitability that sports betting will be part of this country's armament of legal entertainments, first state by state, and then nationwide, once Congress does what the NFL has asked it to do and establishes a "regulatory framework" that protects "the integrity of our game" and ensures both the league and its players a piece of the action. Football was always a game made for gambling; now gambling will be made for the game, and that will count as both a rebirth and an ending. There has long been an "arrangement" between the NFL and gambling interests, whereby the sportsbook guaranteed the league a captive following and the league offered in return its most valuable intangible asset: legitimacy. But that arrangement has been dissolved by no less august an authority than the Supreme Court, and the league will one day earn a portion of its revenue from an activity it has tried to keep at arm's length. What becomes, then, of its legitimacy? What becomes of the quasi-legal and quasi-illegal interests once the quasi is gone? Who will turn out to be the gangster behind the gangsters? What, in the end, is the difference between placing a legal bet and an illegal one, and will something irreplaceable be lost when any upstanding citizen with a few bucks and a smartphone can bet a football game ... and the promise of the connection gives way to the reality of the transaction?

I wish my father were alive to answer that last question, but he died 12 years ago, flat broke. He never bet another football game after moving down to Florida. He played the stock market instead, an industry in which the touts and the bookmakers are fused into a corporate entity. He did not invest; he gambled on long shots or, as he called them, "s--- stocks," with the same degree of acumen he brought to football. By making nothing but legal bets for the last 20 years of his life, he probably avoided having his legs broken. But he lost precisely what he was out to win, which was everything, or everything but my mother, who stayed with him to the bitter end. His desperation is what survived him; when I cleaned out his apartment after he was gone, there was a paper trail of stocks of which I'd never heard and, spilling out of the drawers of the dresser in his bedroom, a thick mulch of lottery tickets, like the end of a ticker-tape parade.

What is the difference between legal and illegal gambling? For losers, there is very little -- they both provide avenues to ruin sufficiently wide and well-traveled. The difference is in the winning, or in what people like my father expected to win when placing a bet. It wasn't just money, because an illegal bet wasn't just a financial transaction. It was a cultural event, a vote for vice. It was a choice about where and how to live in relation to the law, moral and otherwise. My father wanted to live outside it, though within the borders of family. He gambled because he liked, as he always told me, "a little action, a little interest," and because life lacked savor without "a little larceny." He wanted to get away with something, and until he ran out of cash, he did -- he made people think he was a gangster when really he was just a mark. Even at the end, when he was reduced to trying to "beat" the lottery, he remained optimistic about the transformational power of a wager: "Wait 'til I win," he said. "Then I'll show you how to live." But he didn't have to win in order to do that. He just had to put the paper in front of me with the Latest Line, hand me what was left of a pencil and ask me who I liked.