John Coltrane left his wife in the summer of 1963.

He wrote two songs for her; both were melancholy.

He said the first song was his favorite. He wrote it like a love letter, and like all love letters, it was a time capsule. Within: a house in Philadelphia, a house party in New York, a conversation about harp music and another about laughter.

The woman he left was the love of his life. He spoke softly to her when he could and not at all when he could not. He was afraid of speech, of what it could and couldn’t do, of where it failed in the same way that names and titles do. When he decided to leave her, he was afraid of what speaking would do, where it would fail and why it would hurt. He was afraid of stillness, of mediocrity, and of her.

He entered the room where he hoped she would be, closed the door, and looked for her in the shadows on the wallpaper. Her feet were tucked between the cushions of an armchair. She was pretending to read.

Again, he felt her music, her melancholy. He wanted to tell her he had written a song for her. Don’t you remember how I played it, how you cried?

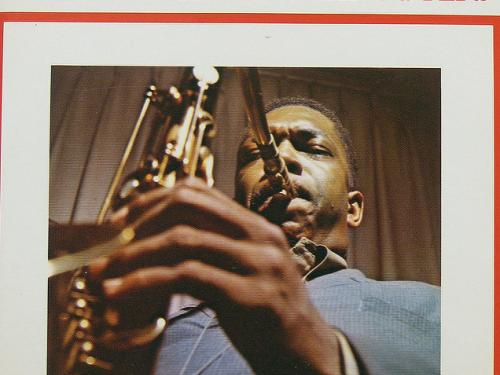

On the album Giant Steps, there are three songs named for people. The first is called “Cousin Mary,” the second “Syeeda’s Song Flute,” the third, a long exhale called “Naima.”

When marriages end, it is because a decision has been made. At its best, this decision might resemble a mercy killing, a choice to end a once sweet thing gone sour beyond its potential return to sweetness.

It has been written that John wanted to start another family, that something had grown stale and poisonous, and while it is not impossible to start a new family without excising the first one, it is harder to begin anew with what is left of the old.

And so, when he said “I have to,” he was telling at least part of the truth.

Naima might have sat cross-legged on the bed. She might have hoped he was lying to her, that he would take it back. She had not decided anything in years.

She knew from the way he played and the way he moved that he was sleeping with someone else. She did not act on her knowledge, and saw for every day she didn’t speak that inaction was either decision or paralysis.

She knew he was driven by something invisible to her, as if he had long ago decided to search on stages where the air was thick with smoke, in practice rooms shaken by scales.

And so, she sat on the bed and knew that what she wanted him to take back could not be taken back.

He said, “Naima, I am going to make a change.”

Then, he tried to look instead of speaking, as if his gaze would be enough.

She thought that the ability to look at someone like that was a cruel power; the look that had drawn her to him was the one he used to break her.

John decided to kill what had grown sour. He entered the room where he hoped she would be, shut the door quietly behind him, sat on the bed, looked at the ground.

Naima decided to take a job and to love her child.

The third song: a long exhale called “Naima.”

Because I was not present at the time of my naming, I know it as a story, an old photograph. When I was a child, my parents would pull both from their lips or from a box. They would place the photograph on the kitchen table, where my mother would sit smoking, and I would trace patterns in the clouds of her breath, listening to them talk about who I was, what I had chosen.

The photograph shows my mother, heavily pregnant in the front seat of a U-Haul, smiling as if she is proud to be there. The story is as follows:

When she discovered she was pregnant, my mother left the PhD program at Harvard and looked for a place to live in upstate New York. She drove up and down along roads lined with houses where the confederate flag is an implicit staple; as a child I saw it on walls, tucked into drawers, worn in the form of pins that were meant to be subtle in their violence.

It is a long-held belief of my mother’s that babies can communicate from the womb via psychic interference. When the song John Coltrane wrote for Naima Grubbs came on the radio, she decided I was communicating my name, but also my blackness, assurance that even if my skin was as light as her husband’s, my name would be Philadelphia jazz.

My mother’s name is Mary.

I left her home at seventeen, when something grew stale and poisonous. We have since been able to speak about a small number of things. For example, we can talk about race and about songs.

We cannot talk about living or about sadness or about the particulars of our lives: I don’t tell her who I am dating; she does not tell me when she has lost another friend.

When I am not with her, I think of things we can talk about. I order them in my head and plan to speak them as though to alleviate an unspoken heaviness: a memory of her singing Nat King Cole’s “Unforgettable” and touching lightly the tip of my nose with her finger; Prince’s Musicology concert in Pennsylvania, a new video of him performing, which she will play on the television in some tiny living room, nodding and dancing and calling him a genius.

The day he died, I received an email from her with the subject line “Oh My,” and felt guilty for my distance and my emotional unavailability.

The next time I called home, it was shortly after his death, and my brother was turning eighteen. My mother, drunk, said they were in deep mourning. I think the expectation was that I would mourn too, but I am afraid of mourning, and so I said very little.

John, drunk, came home some nights and stumbled into the living room, and when he did not come home and Naima imagined him stumbling in smoke-filled rooms full of desperate music, she felt as though her stomach had been emptied, its contents replaced with something vast and dark.

The first time he looked at her, it was at a party. People were smoking around coffee tables, and she felt his gaze before she saw it. When she met his eyes, they were appreciative and warm and dark. He told her she shouldn’t wear the belt she was wearing, told her something plainer would suit her better. The next thing he said was that he didn’t talk much. She would think, later, that it was funny for him to have said that and then talked the whole night about music, about being, and about heaviness.

He asked her, softly and politely, to give herself to him. John only ever asked for things politely.

My mother decided on the fact of my poison while I hovered in the narrow doorway between the kitchen and her office:

“You are a heartless child,” she said.

Heartlessness, I thought, might be a kind of strength.

My brother is named after the musician and not the music. He occasionally tells me things I do not want to know. For example, he tells me that my mother’s drinking has gotten so bad she is forgetting to take dinner out of the oven. The small living room off the kitchen fills with the smell of smoke.

I feel, because I am older and because I am named after a song, that I should know exactly what to say.

Because I don’t know what to say, I say things that have grown hollow and feel guilty for my emotional distance.

He tells me he doesn’t understand, and though I also do not understand, I often pretend to. Emotional distance is achieved, sometimes, through a pretense of understanding.

The musician: a bassist with the Chicago Jazz Ensemble.

I wonder if, when Syeeda got a flute from her stepfather at her high school graduation, she wanted never to touch it again, if she ever sat in the back of an ambulance, or listened to the paramedics talk about alcohol poisoning, or wondered if now was an appropriate time to cry.

Wondering is, some of the time, a way of asking, a kind of hope or appeal. The hope is that poison will, in the future, lose its power.

John Coltrane ended his heroin addiction by lying in his bed, sheets stuck to his body with sweat, until he could hardly breathe for shaking. He asked his wife to bring him water and only water.

He might have asked in response to a knock on the door, a quiet inquiry, an “Are you all right?”

She might have stood outside the bedroom holding a glass of water in one hand and a dishtowel in the other. Her daughter’s footsteps might have sounded on the stairs. Barefoot and beautiful was her child, who pressed against her mother and asked when dinner would be ready.

She said, “Hey baby girl,” and pitched her voice low so the trembling was only in her hands.

She opened the door and looked for him in the sheets on the bed. She placed the water on the bedside table and removed the old glass, which he had drained. His eyes were open because he was afraid to let them close. They were good eyes, but she saw in them now a kind of worship, and it scared her.

She had seen the same kind of worship when they had met at the party, had felt it in the songs he had written for her, felt it pool and deepen in the song he had written for her daughter.

Two nights before, he had sat up in bed and begun to speak. He said her name, said “I’m through,” and she felt as though the dark she had only ever glimpsed was pressed against her organs.

She waited for him to say something that wasn’t what she thought he was saying, and until he did, her breath caught somewhere in her chest and refused to leave her body.

He said he was going to stop drinking, stop smoking, stop doing drugs, said also that he needed her help. Naima felt a relief which seemed, for a moment, like pain. She wanted to say he didn’t need to ask, that she would help him until her dying breath, that he was the only person she had ever met who could destroy her with a look, the only one who was afraid of speech, the only one who recognized what words could do.

And so when he asked if she would back him up, she said, “You know I will” and meant it.

Coltrane’s music is a living thing. To listen is to hear it breathe; the slow push of the horn at the beginning of “Naima” is the first breath of a long exhale. Listening to Giant Steps at night from the stereo of a moving car is like pulling stale air from one’s body, freeing the limbs, allowing it to move again.

Someone is usually in more pain than I am. For example, my brother was always sick, and because we were very poor, we could afford his medication and not much more than that.

He has never been afraid in the same way that I am. For example, when he asked my mother to stop drinking, it was because he was hoping for an exhale. I think, whenever they are fighting, that it might be my fault, or that I have succumbed to the same inaction that is akin to paralysis.

The first time, we were gathered in the living room of some small apartment. There was a couch, a long green table, and a mess of a kitchen.

What my brother said, what I was afraid to say, was, “You need to stop drinking.” I don’t remember what was said before or after.

Here is what I remember: the look on my father’s face, her exaggerated nodding, her finger stirring an olive into some kind of liquor. I did not look at my brother, examined, instead, my hands, knotted into the quilt on the bed, which sits in the living room because there is nowhere else for me to sleep.

Here is what I remember: thinking that because it was after six o’clock and she was already drunk, she would wake up not knowing what had been said the night before.

John Coltrane ended an alcohol addiction, a heroin addiction, and a marriage.

My mother has ended neither her addiction nor her marriage because the fact of their poison remains a naked and unknowable truth.

John was afraid that speech might fail. Naima was not afraid in the same way he was, but she understood that music was a way of speaking and held, inside itself, an expectation.

She knew more about music than he did. It would play in her small and dirty home when she finished building sewing machines. Her parents had sounded Bartók through the house; as a child, she had listened.

They sat, one night in a darkened bedroom, where they listened to a recording she had taken of a solo he had played on a stage where she watched him habitually.

He asked her what it was he was hearing. She knew then that she was somehow important, that she had been granted access to the world he had built in his sequestration.

She said it reminded her of Daphnis and Chloe. They listened again, in silence, and she thought she heard arpeggios.

He asked, eventually, what instrument he was hearing. She rested her chin on a closed fist and fought exhaustion so she might better notice the tenderness she felt when she looked at his eyes. “There’s a harp solo,” she said.

John thought, when he asked Naima for help or advice, that she seemed deep and soulful.

When she stood outside his bedroom door and held a glass of water in one hand, she did not feel deep and soulful. She felt as though she would break with fear. She told her child when dinner would be ready.

Naima did not ask for things because she was afraid if she needed people, people would not also need her. The only people who seemed to want her were the people who also needed her.

When John asked her to marry him, he did it as if he were asking for a glass of water.

They sat across from each other at a diner. He looked at her and said, “I’m going to marry you.” She smiled because she couldn’t help it, said, “How do you know?” Said, “You haven’t even asked me yet.” He said, “Well I’m asking you now,” and she thought nobody would ever ask her something that made her shiver the same way.

I feel my identity is composed of a series of expectations and a subsequent failure to meet them.

For example, my loved ones expect that I will not be distant or emotionally unavailable.

For example, when I said to my brother that his alcoholic mother was an unhappy person, I was really saying “Please excuse her behavior,” but he is her child, there is no excuse, and I might as well have said nothing at all.

I feel, sometimes, that communication through psychic interference, were it possible, would do more harm than good because it would consist, necessarily, in the revelation of naked and unknowable truths.

For example, my mother does not need to know that I have, in the past, thought things would be better if she left my father, found a home for herself somewhere far away, if we visited her only on weekends.

When my brother asked her to stop drinking for the second time, he was no longer hoping for an exhale but fighting suffocation.

My mother once asked me if I was trying to hurt her.

I didn’t know the answer, but I knew anything I said would be a lie, in the same way that it is a lie when I tell her it is good to hear her voice.

Her voice has several cadences. My favorite emerges when she is on the phone with her friend from South Chicago. My least favorite is the slurred confusion that comes every evening like clockwork.

I wonder if Coltrane had similar cadences—arguments slurred, music warm.

I wonder if Naima ever sat in darkened rooms, listened to an album named for movement, and wept for what she once had.

We are the same height. She was married in the same month I was born and died the year after, and I was named for the song named for her.

I feel, in the absence of psychic interference, that I am lying constantly.

Music is a better way of speaking than speech is because it does not consist in words or names; those things are put there later as a means of failed signification.

I wonder if, in listening to a song called “Wise One,” I am implicitly associating myself with the expectation that I be wise.

I wonder if, in listening to a song called “Wise One,” I am looking for advice from the person who is its subject, its namesake, its object, and who might, loosely, be my namesake, object, or subject.

My mother once told me, drunkenly, that I was stupid and foolish.

A friend once told me, drunkenly, that I was wise.

Had I not been drunk, I would have told him he was wrong. Had I been honest, I would have told him that when a child is told repeatedly that she is stupid or lazy, her stupidity and laziness become deeply rooted convictions and cannot be undone by words that come later.

We took my mother to the hospital on Mother’s Day, and since there was only room for one person in the back of the ambulance, I sat there alone and wondered if now was an appropriate time to cry.

The same friend, when it was over, hugged me in the way people do when they do not know how to help you.

I was, just then, incapable of any kind of emotional distance, capable only of intense cruelty.

For example, when I was a child, there was never a time when my mother was not beautiful, but in the back of an ambulance, all I could think was that her flesh resembled uncooked bread.

She once sang to me, touching my nose lightly with the tip of her finger, that I was unforgettable.

Some people are aware of speech, of what it can and cannot do, of where it fails in the same way names do.

For example, some friends, when you tell them you took your mother to the hospital today, will say, “Oh my god,” and then not say anything, choose instead to nudge you with one shoulder after the silence has stretched.

There are three people that named me, and my father is not one of them, but when I once hummed the first three notes of a particular song and asked him to guess, he knew what they were.

I wonder if Naima Grubbs ever felt her identity was composed of a small series of expectations, if she felt the weight of them. I wonder if she ever sat in the back of an ambulance.

The weight of having a song named for you may exceed the weight of having a person named for you; a person, unless that person is my mother, does not propose or impose a characterization for or on the person for whom they are named. People are not time capsules in the same way songs and letters are.

“Wise One” was a retroactive time capsule, designed for capturing what is visible from a vantage point offered by emotional distance.

Characterization is also sometimes expectation. For example, if you are called wise, the expectation is that you will be. For example, if you are emotionally distant, the expectation is that you are also cold. For example, if you are called Naima, the expectation is that you will say I’m Naima, and it will resonate every time you do.

The first three notes of the song called “Naima” are C, B-flat, E-flat.

In order to change a scale from harmonic to melodic, it is necessary to flatten certain notes.

To flatten a note on the piano is to move it down a half step so that its sound is eerily altered.

It is easier to flatten notes on a piano than it is on a tenor sax. In order to flatten a note on the tenor sax, your fingers have to move with your breath. In order to flatten a note on the piano, your fingers have to move.

To listen to a song is to experience what it captures; a house in Philadelphia, a house party in New York, a conversation about the harp, another about laughter. Music is a way of speaking. It holds, inside itself, an expectation.

In order to play “Naima” on the piano or on the tenor sax, the musician must understand that its resonance and its melancholy are the result of practiced flattening.

It might also be necessary to understand that the notes will fall instead of rising and linger where they have fallen, as if afraid to stand again.