Last month, industrial performance artist and provocateur Genesis P-Orridge performed her final concert at London venue Heaven. It wasn’t just a farewell to her audience, but also a means for Genesis P-Orridge to bid farewell to herself. Recently she told the New York Times that the course of her chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia meant that she had “less optimistically, a year, maybe six months. And then I’m on the downward slope to death”. As with the Fall’s Mark E Smith in January this year, it’s difficult to imagine the UK music underground without this constant fixture.

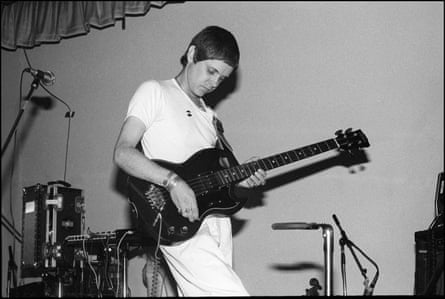

Roughly half a century ago, Genesis P-Orridge flitted between several artist collectives. After dropping out of Hull university, she met avant-garde performance artist Cosey Fanni Tutti before joining the Ho Ho Funhouse art collective in London. Then a couple, the pair created the supposedly egalitarian, hippy collective COUM Transmissions and developed keen ideas around art’s purpose in society: namely, “art as life”. Fanni Tutti, Chris Carter and Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson and P-Orridge formed the industrial noise project Throbbing Gristle, who vowed never to rehash their albums live, aimed to be more antagonistic than punk and were bestowed the title “wreckers of civilisation” by Conservative MP Nicholas Fairbairn following their pornographic Prostitution exhibition at London’s ICA in 1976. Seeking to juxtapose the monotonous sounds of factory work coupled with controversial reappropriation of totalitarian symbolism, Throbbing Gristle gave Genesis P-Orridge her reputation as the “godperson of industrial music”. An extraordinary life, no doubt – but to what extent can it be celebrated?

That recent New York Times piece shows ambitious, radical bodily transgression to be the overarching theme of Genesis P-Orridge’s prolific creative life, a fascination that began with her teenage love of German dadaist artist Max Ernst’s surrealist corporeal mashup, The Hundred Headless Woman. P-Orridge would leave behind her past identity as Neil Andrew Megson, and, decades later, participate in body modification in order to become a cosmetic “double” of her partner, the nurse and dominatrix Lady Jaye, in what P-Orridge termed the Pandrogyne Project.

Lady Jaye died in 2007, but P-Orridge continued with cosmetic surgery to alter her own body, part of her continuous striving to exist as a work of art. While P-Orridge and Lady Jaye might have conceived of a new kind of human relationship – a radical reconsideration of the self in relationship to another – it seemed strange that the New York Times didn’t consider P-Orridge’s status as body provocateur alongside Fanni Tutti’s allegations. In her 2017 autobiography Art Sex Music – she says P-Orridge was a manipulative, cruel partner. Fanni Tutti reveals another side to P-Orridge’s story, in which her own artistic freedoms and body, which she also considers interchangeable, are controlled and oppressed by her then-lover and bandmate.

Fanni Tutti recalls a series of alleged incidents in Art Sex Music, all denied by P-Orridge to the New York Times: how P-Orridge threw a concrete block at her head from a balcony, apparently aiming to kill her, and missed. How she allegedly pressured Fanni Tutti into frequent unprotected sex, which led her to seek an abortion. How she ran at her with a knife after Fanni Tutti threatened to end their relationship. How P-Orridge appointed herself chief supervisor of COUM’s frequent orgies and expected Fanni Tutti to have sex with various friends “instigated by and shared with [P-Orridge]”. There are repeat alleged incidences of P-Orridge forcing Fanni Tutti out of their shared living space.

The New York Times referenced Fanni Tutti’s allegations in a slim, sceptical paragraph. P-Orridge’s response: “Whatever sells a book sells a book.”

Former COUM member Foxtrot Echo also suggests in Art Sex Magic that P-Orridge’s genius didn’t lie in her artistic skills, but rather in her ability to manipulate others. One key COUM member, Spydee, left the group after confessing to Fanni Tutti his frustration that P-Orridge “just wanted followers, not people to contribute. [She was] very dominant, we had no fun.”

In an interview with the Quietus, Throbbing Gristle’s electronics supervisor Chris Carter admitted that this tension drove the group’s sound – at least until their first split in 1981, after P-Orridge departed. Still, it was Carter’s DIY circuitry that fuelled their constant experimentation and unpredictable live performances. Throbbing Gristle created a sublime terror through their combination of imagery and sound. This, they explained, was their attempt to reveal the hypocrisy of British conservative politics, to strip back the safeness and niceness of “ordinary society” to show what humanity was truly capable of. In the early 90s, Scotland Yard’s Obscene Publications Squad raided Genesis P-Orridge’s house and discovered a fascination with necrophilia, murder and Nazism; Genesis herself has reminisced about art performances involving enemas of blood, milk and urine, or masturbating with severed chicken heads.

In his book on the history of British esoteric music, England’s Hidden Reverse, David Keenan argues that: “To take morality so seriously you have to pick it apart yourself in order to rebuild it in the face of the truth of existence, in all its horror and beauty, is intensely moral.” But for some, adopting such imagery is still a seductive means to signal extremist allegiances, while operating under the veneer of explorative artistic “transgression”.

After leaving Throbbing Gristle in 1981, Genesis P-Orridge’s new band Psychic TV at times adopted a more straightforward garage rock setup (though perhaps with a little ironic distance). One of their most well-known tracks, the scrappy, Buzzcocks-esque Godstar, had P-Orridge recount the tragic life of the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones, commenting on the shallowness and destruction of fame. This anti-pop pop song clawed its way into the UK charts, surely something P-Orridge would have sniffed at during the Throbbing Gristle days. Other Psychic TV works continue Throbbing Gristle’s sound collage approach, but they’re sorely lacking Chris Carter’s metal machine music – their track Discipline sounds as if it’s driven by the irregular heartbeat and screams of Linda Blair, the demonically possessed girl in The Exorcist.

Psychic TV has continued well through the 80s and P-Orridge has released 37 studio albums with the band since its conception. In 1993, P-Orridge moved with Lady Jaye to Ridgewood, Queens in New York where the pair began the Pandrogeny Project, identifying themselves singularly as “Breyer P-Orridge”. In a recent documentary by French director and curator Marie Losier, The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye, P-Orridge is shown to be heartbroken, weak, struggling to pay the bills. But Losier allows P-Orridge to steer the course of the film away from the more controversial, problematic aspects of her early years – a celebration bordering on hagiography.

Artists that push for the representation of progressive lifestyles and new ways of framing identity should not be denied a platform, but their actions cannot be swept under the rug if they do not fit with their projected image – or even worse, glamorised as part of their transgression when they are plainly harmful. As Andrea Long Chu stated in her masterful disassembly of non-binary writer and director Jill Soloway’s memoir, She Wants It: Desire, Power, and Toppling the Patriarchy: “The ethics of gender recognition, now more than ever, compel us to accept without contest or prejudice the self-identification of all people. They do not, however, compel us to find those identities likable, interesting, or worth writing a book about.”

As the Quietus warn in their essay on extreme politics in underground music: “Artistic transgression and subversion are vital elements of any socially progressive culture, but mindlessly pushing against the boundaries of what is considered acceptable, artistically, politically, or socially, is not necessarily progress.” Legacies place an artist’s fingerprints on scenes and communities, that linger even in their absence, and P-Orridge is certainly interesting enough to write a book about. But Fanni Tutti’s accusations are now part of this legacy – and anyway, with such an unruly personality, P-Orridge herself would likely reject a straightforward, purely celebratory account of her life. Histories of our artists must be written honestly and sometimes even painfully – otherwise our civilisation will truly be wrecked.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion