The most eagerly awaited arrival in Jamaica since Ethiopia’s Emperor Haile Selassie touched down in April 1966 might just be this weekend’s return of Mark Myrie, better known as Buju Banton.

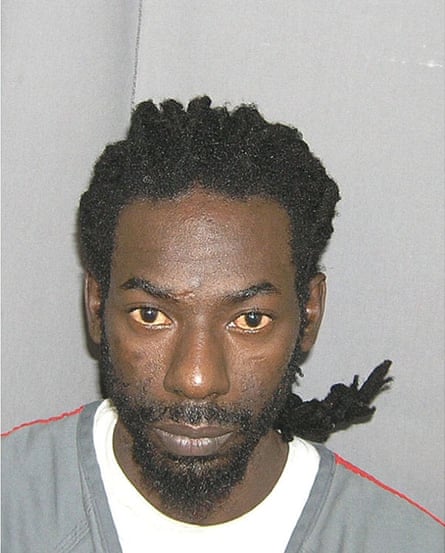

Myrie, perhaps the most famous Jamaican artist whose name isn’t Marley, has served seven years in a US prison after being found guilty of intent to deal more than 5kg of cocaine. On 8 December, the gravelly voiced rastafari artist will be put on a plane in Florida and flown to Kingston to a nation that has been eagerly awaiting this moment.

Jamaica’s culture minister, Olivia “Babsy” Grange, reports that Banton “is now really about, from what we understand, employment of young people. If he can help shape and resocialise young people, that is something we should embrace.”

That said, the government isn’t pulling out any stops. “We can’t give him a hero’s welcome,” says minister of national security, Horace Chang. “He committed a crime.” And yes, Grange agrees, “There’s no getting over the fact that he was convicted, but Buju was loved long before he was convicted and he will be loved just the same, even if he comes home in handcuffs.”

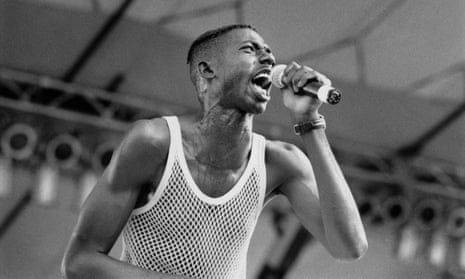

Raised in Salt Lane, a poor area of Kingston, the man nicknamed Buju by his mother honed his craft as a child, performing live with soundsystems under the name Gargamel aged 12 and recording by the following year, 1987. Jamaica fell for Banton in the early 90s, when he established himself as arguably the most significant dancehall artist in the country.

Banton was beloved for his baritone grit, raunchy songs such as his ode to short shorts, Batty Rider, and his responsiveness to his audience. When some fans felt excluded by his hit Love Me Browning, about a penchant for lighter-skinned women, he followed it up with the equally catchy Love Black Women.

Reggae artist Protoje says: “There is nothing that he cannot do musically. He’s a prodigy. He was awesome from 18 years old. He is one of the greatest artists to ever do it in Jamaican music, so I would never count him out.”

In 1992, he overtook Bob Marley’s record for No 1 singles in Jamaica and signed with Mercury Records. Less happily, he also released the most infamous Jamaican song ever recorded, Boom Bye Bye, which openly incited the killing of gay people. It received local and international condemnation, culminating in the the Stop Murder Music Campaign, organised by UK group OutRage! in collaboration with Jamaican LGBT-rights group JFLAG.

The campaign ultimately led to concert cancellations – 28 of Banton’s were cancelled between 2005 and 2011. In June 2007, he signed the Reggae Compassionate Act, which meant he agreed “to not make statements or perform songs that incite hatred or violence against anyone from any community”.

Banton wrote Boom Bye Bye when he was 15, and has since found other lyrical topics. In 1995, he released the critically adored ’Til Shiloh, which embraced rastafari consciousness and demonstrated his versatility, as fluent in hardcore dancehall as roots reggae.

Since his imprisonment in 2011, a new generation of reggae artists have gained global success, and Banton will have to compete with with likes of Jah 9, Raging Fyah and Kabaka Pyramid; Chronixx and Protoje drew 10,000 fans to London’s Alexandra Palace only last month. “The last album he released prior to his incarceration was Before the Dawn, for which he won a Grammy,” notes Sonjah Stanley Niaah, author of Dancehall: From Slaveship to Ghetto. “What’s interesting to me is that Buju will have to come to terms as a stage presence with a reggae revival.”

Artist of the moment Spice, real name Grace Hamilton, is excited about what might accompany Banton’s return: “It is extremely significant to the genre because his music uplifts our roots and culture. His first concert in Jamaica will prove that. I’m sure mass amount of tourists will travel to our island just to see the great Gargamel.” Banton’s Long Walk to Freedom tour (named after Nelson Mandela’s autobiography) will reportedly begin in Jamaica on 23 March.

It’s rumoured that Banton has been writing songs and reaching out to potential collaborators. There is at least one album that is ready to go. UK producer Blacker Dread released the tantalising Stumbling Block single last year, one of a range of tracks recorded in the early 2000s, put off due to the death of Dread’s son in 2004 and then Banton’s imprisonment. “Man is a king,” says Dread, “I have tracks with Buju that are timeless.”

Unlike the similarly revered dancehall artist Vybz Kartel – whose 2014 conviction for murder led to a life sentence that will see him serve at least 35 years, yet who still seems to be able to release track after track – Banton has been all but silent. In a statement to the Guardian, he described the impact of imprisonment and his means of coping. “Prison can be traumatising not just on myself, but on my family as well as emotionally draining,” he explained, “For me, I drew strength from immersing myself in my situation. Do not live in yesterday but live in today. And education was the only thing that kept me up and alive. I immersed myself in reading so much – theology, philosophy and other subjects.”

Human rights activist and former member of OutRage! Peter Tatchell is confident that Banton will continue to put the past behind him, stating that “it would be even better if he could acknowledge and apologise for those violently homophobic lyrics, but the main priority is that he doesn’t continue and repeat them.” Dane Lewis, former director of JFLAG, states that “the reality is that [in Jamaica] the most vulnerable continue to face some extreme forms of homophobia ... but in the last 10 years we have seen some shifts regarding homophobia and the ways LGBT in the region experience life.”

In many ways, Banton is coming home to a vastly different Jamaica. The Kingston he knew is now populated by shiny new high-rises; the economy is healthier with record low unemployment, and the music scene is always changing, with the UN designating reggae as an “Intangible Cultural Heritage”, soca-soundtracked Trinidadian-influenced Carnival exploding in popularity, and major radio stations blaring top 40 music from the US. Yet Banton, even if only musically, will likely slip back in with ease.

Rory Gilligan, a founding member of the famed Stone Love soundsystem, which helped establish Banton’s career, says the artist will have a relatively seamless transition, at least in comparison to other involuntarily returned citizens. According to Oswald Dawkins, president of the National Organization for Deported Migrants, about 1,500 people are involuntarily returned to Jamaica from the US, the UK and Canada every year. “I think he will adjust very easily. He has no financial problems. He has the resources,” Gilligan says. “There is nobody who has anything bad to say about him.”

DJ Agent Sasco might agree, especially when it comes to the airwaves and dancehalls, which are crying out for fresh Banton tracks. Sasco – whose first recording was produced at Banton’s Gargamel studio – insists that the star will likely bring a sound that is unique to the present. “Don’t expect that it is going to be 2006 or 1994, but just to take him in 2019 and wherever he is at as a person and an artist,” he counsels. Then again, in the rush of enthusiasm for his return, whatever Banton releases is due a rapturous reception: “He could put out a single of him singing the ABCs and it would be a huge success.”

In one of Banton’s most memorable songs, Destiny, he speaks of wanting to chart his own future, singing “my destination is homeward bound … I know I must get through no matter what a gwaan”. As the prodigal son returns, finally his destiny is back in his own hands.