The End of the NBA’s G.O.A.T. Era

LeBron James has just started his next act with the Lakers. But when he retires, what will become of the endless debate over which player is the Greatest of All Time?

Since LL Cool J released his album G.O.A.T. (Greatest of All Time) in 2000, the acronym has been a cultural touchstone—used to spark arguments about who deserves the title in any given profession. Perhaps nowhere is the debate over who holds that honor more intense than in professional basketball. Determining which NBA player is the G.O.A.T. requires consideration of both objective statistics (such as championships won or points scored) and subjective criteria (such as who was a true leader or managed to be more successful with worse teammates). As the sport changes, so do the arguments and rubrics. In the 1960s—before the acronym was conceived—debates about the NBA’s best centered on nigh-seven-footers such as Bill Russell, who won 11 championships in his career, and Wilt Chamberlain, who once scored 100 points in a game and averaged 50 points for a season. In the 1980s, the honor went to showmen such as Magic Johnson and Larry Bird.

Now the contenders for G.O.A.T. have been whittled down to two opponents who have never even set foot on a court together: LeBron James, who has lorded over the 21st century as the sport’s best player, and Michael Jordan, who ruled the 1990s with six championships. The LeBron vs. Jordan battle has become a defining clash of the sport’s current era, litigated in barber shops, bars, and living rooms across the U.S. It’s true that LeBron has just begun the next phase of his career with the Los Angeles Lakers after leaving his hometown Cleveland Cavaliers squad in the off-season. But his retirement, presumably within the next decade, could help usher in a new way of talking about greatness in basketball: one where vigorous, varied debates about individual players and teams as a whole replace simplistic, mythmaking discussions about godlike talents.

The LeBron-or-Jordan question first emerged in 2002, when a high-school junior from Akron, Ohio, appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated alongside the words The Chosen One. The implication was that this rising star, a 17-year-old James, was the heir apparent to Michael Jordan, whose career was ending for good after a stint with the Washington Wizards. Maybe one day, the cover teased, James would supplant Jordan as the greatest basketball player ever.

In the 16 years since, the issue hasn’t been settled. James’s accolades throughout his career—namely eight straight NBA Finals appearances, including carrying last year’s Cleveland Cavaliers with a subpar supporting cast to the finals—have only narrowed the gap between the two, making their standings more a matter of personal preference than anything. Just this past off-season, articles comparing James with Jordan appeared in Sports Illustrated, USA Today, Slate, and Newsweek, without any definitive answer as to who comes out on top. Mike Greenberg opened a May episode of ESPN’s Get Up! by declaring that there’s no clear better player between the two, while Charles Barkley concluded the NBA Finals by threatening to slap anyone who dares compare LeBron with Jordan.

One reason the LeBron vs. Jordan debate is particularly interesting is that the former is still playing, thus still accumulating new moments and stats for his legacy. However, James is 33 years old and a 15-year veteran of the NBA, which means he’s in the final stages of his career. Once that career ends, so will the new ways to compare him and Jordan. When he retires, the NBA will be in the unusual position of having no active players vying for that coveted title.

Why are there no clear potential G.O.A.T.s right now? Let’s start with the other top players: The Warriors’ Kevin Durant is James’s closest current rival, having won the NBA championship against the Cavaliers the past two years in a row. But by joining the Golden State super team, he’s stifled some of his scoring potential and chances to win MVPs; pundits such as ESPN’s Stephen A. Smith have even called Durant’s decision to join a 73-win behemoth—rather than pulling a team to a title as Jordan did—“weak.” For many fans, this general backlash seems to have made Durant ineligible to become the G.O.A.T.

His teammate Stephen Curry suffers from playing alongside Durant for some of those same reasons. Additionally, Curry’s early-career ankle injuries have hindered his ability to climb the ranks of all-time assists and points due to the amount of games missed—despite him being widely acknowledged as the greatest ever shooter. Curry and Durant are likely to get into top-10 or even top-five conversations, but the G.O.A.T. is unlikely. Players such as James Harden and Russell Westbrook won’t accumulate the championships needed to enter G.O.A.T. contention as long as the Warriors are dominating the NBA, which they’re primed to do for the next few years.

Ben Simmons, the Philadelphia 76ers rookie, is the closest to James in terms of skill set. His eight triple doubles last season is LeBron-esque, but his 15.8 points per game are a far cry from LeBron’s 20.9 during his rookie year and Jordan’s otherworldly 28.2. Simmons’s teammate Joel Embiid is a generational talent as a center, but he missed his first two seasons with foot injuries, so his long-term health is a concern. Milwaukee’s Giannis Antetokounmpo is only 23 and a wild card for ruling over the league in the future. At nearly seven feet tall, he has all the tools for greatness, but he still needs to develop a jump shot and prove he can carry his team deep into the playoffs.

Probably the best bet for being the top player in the league for the next decade is Anthony Davis. He’s only 25 and is a top-three candidate for MVP this year, putting up 28 points, 11 rebounds, and 2.6 blocks for the 2017–2018 season. The league has never really seen anyone like Davis, who is also almost seven feet tall, can shoot threes, and beat any player off of the dribble while being one of the most disruptive defensive forces. But he still needs to rack up enough championships.

Lastly, if we go even younger, no high-school or college players are making headlines or garnering buzz from scouts as James did in 2002. Even sensations such as Zion Williamson, the 6 foot 7 Duke freshman who was going viral for looking like a man playing against toddlers throughout high school, aren’t getting compared to LeBron or Jordan. Maybe these high-school players don’t show the same promise that a young James did, or maybe the sports media now knows better than to put the pressure of being transcendently great on teenagers.

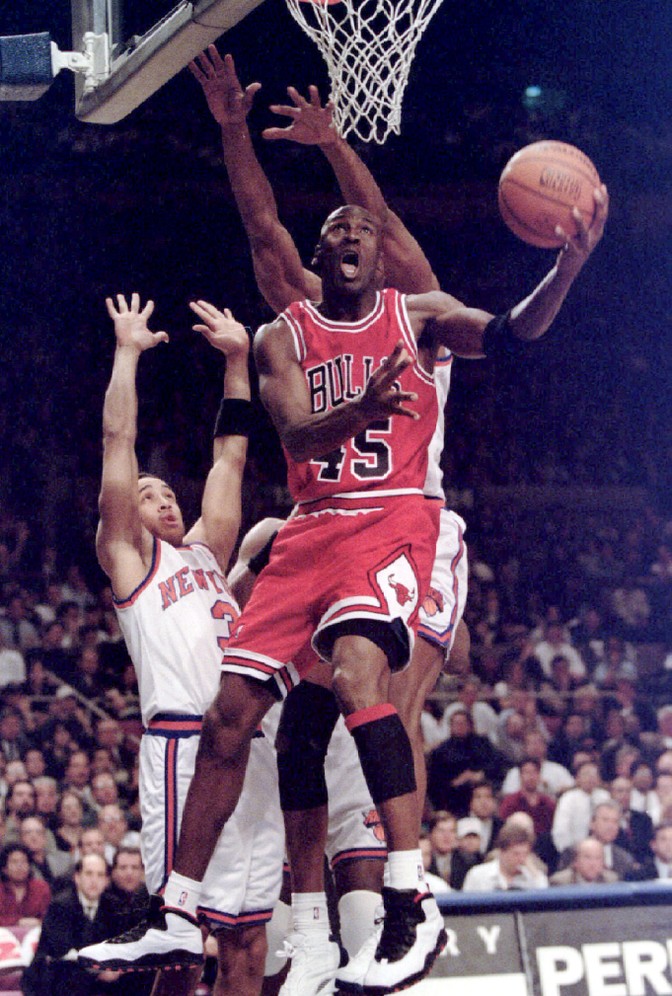

If the end of the G.O.A.T. era is indeed upon NBA fans, it would mean the death of a debate about greatness that has framed the league’s story lines nonstop for the past three decades. On April 20, 1986, a 23-year-old Michael Jordan scored 63 points against the Boston Celtics—one of the greatest teams ever assembled—a still-standing NBA playoff record. Afterward, Larry Bird said he played against “God disguised as Michael Jordan.” The Chicago Bull would validate that position by winning three straight championships from 1991 to 1993 before briefly retiring. At that point, Jordan’s status as the G.O.A.T. was still tenuous. Winning three titles and three MVPs were accolades that past stars such as Bird and Johnson had surpassed and that future stars could overcome. The NBA after Jordan’s first retirement was more than ready for its next generation of stars, including Grant Hill and Shaquille O’Neal.

When Jordan retired again in 1998—after collecting two more MVPs and three more NBA championships, cementing himself as the G.O.A.T.—there was Kobe Bryant, who entered the league in 1996. Bryant was seen as a carbon copy of Jordan’s offensive move-set, able to score at will and dominate. The Laker would never become as good as Jordan despite his five career titles, but even in 1998 Bryant at least seemed as if he had the potential to. When the two matched up in the 1998 All-Star Game, the face-off was even billed as a meeting between the present and the future of the league. There was also Vince Carter, who entered the NBA in 1999 and became a better dunker than Jordan, but he could never pull his Toronto Raptors past the second round of the playoffs or even enter into the MVP discussion.

The Bryant vs. Jordan debate endured from Jordan’s last Bulls moment in 1998 until LeBron entered the league in 2003. James’s first game was nationally televised, and superstars such as Jay-Z were in attendance just to see him. The player dazzled, scoring 25 points in that game. He’s only gotten better with time, earning eight straight NBA Finals appearances, three championships, four MVPs, more rebounds and assists than Jordan, and a better field-goal percentage for his career. By the time he retires, James will have more total points than Jordan and at least three more Finals appearances. James is at the very least just as great a player as Jordan. However, Jordan’s 6–0 Finals record and six Finals MVPs are untouchable compared with James’s 3–6 record, and Jordan’s 30.1 points per game are higher than James’s. There’s simply a counterargument for every declaration that James is better than Jordan and vice versa, which is part of what makes the debate so exciting.

But it may be time for NBA fans to shift beyond these exchanges, which are ultimately reductive. The G.O.A.T. label has arguably become an albatross for players like James, whose every loss or missed basket (or decision to join teams that are either too good or not good enough) becomes a referendum on personal legacies. What if talented players didn’t feel the overwhelming pressure placed on them by fans or brands to usurp Jordan or LeBron’s places on their respective thrones? They might feel more comfortable joining or creating other super teams without worrying how that would affect their status. The NBA could see the construction of new powerful teams with enough all-star talent to overthrow the Warriors. And instead of worrying about LeBron vs. Jordan–type debates, the most pressing argument in the sport could center on which dynasty is the best of all time.

Which is perhaps to say that the G.O.A.T. debate won’t disappear; it’ll just evolve. Lately, fans have seen loaded teams such as the Durant/Curry Warriors, the Paul/Harden Rockets, the James/Irving/Love Cavaliers, and the Irving/Hayward Celtics become the new normal at the top of the league, creating unforgettable battles in the playoffs. As a result, NBA postseasons have been as thrilling as ever. James’s 15 years of dealing with unending criticism and G.O.A.T. comparisons were the bridge from the post-Jordan era to whatever comes next. Now it’s time to see what challenges lie ahead for future NBA kings as they chase excellence.