“You see that hill over there beyond the tree line? That’s Canada.”

Pointing northwest, Steve Mason leads me and Cory Heigl, his boss at Packerland Communications, a local internet provider in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, into a fenced-off shack. The simple wooden structure, smaller than a one-car garage, holds a few server blades connected to a 200-foot cell tower outside. It doesn’t look like much, but this shack could hold the key to providing the internet to people who’ve never had access before, those cut off from the modern era by geography and economics.

Packerland’s tower is about 10 miles south of Sault Ste. Marie, a town split by the St. Mary’s River, which separates the US from Canada. In town, you’ll likely get a few bars of cell connection. Most buildings have WiFi that can probably load this website. But head a few miles outside of town, and cell and internet service drops to nil. The big providers—Verizon, AT&T, Spectrum—know that when population drops below a certain threshold, it’s not financially viable for them to build out the infrastructure to service the people who live there.

But it’s not as if no one lives here. Outside of town, large farms divide the land, cows graze the cold grass, and pickup trucks dart from pastures to houses on the frigid October day I was in town. Sault Ste. Marie’s population is around 13,600, but the towns just south of it, Bruce Township and Dafter, have respective populations of just 9,236 and 1,250.

In a community center on an otherwise empty road, a local news crew, Packerland employees, a few local businesspeople and their congressman, representative Jack Bergman, and myself convened to drink coffee and discuss what could be a breakthrough in connecting remote areas to the internet.

Heigl, the general manager of Packerland’s broadband division, thanked everyone for attending, and ceded the floor to Mason, the company’s wireless solutions director. He held up an antenna that looked like something you’d have found on the roof of any house that has TV. And it was—Mason and his team had been working on using radio frequencies allocated to the broadcast industry by the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that aren’t currently in use to deliver internet to people. The concept, using what are called TV whitespaces, is not new—the FCC has been testing it for a few years, and adopted rules to allow companies to use the frequencies in 2010—but few have moved from the theoretical to the realistic.

Packerland has been working with Microsoft to develop its technology as part of the software giant’s Airband Initiative, where it’s using its size and connections to help bring broadband-like internet connectivity to 2 million people in rural America by 2022. Mason demonstrated how his company had developed the whitespace concept into a working product, with Microsoft’s help, connecting his team to companies like Redline, which developed the radio technologies Packerland has been testing.

Giant antennas had been replaced with small plastic boxes. The company’s tower was just down the way from the community center, and Mason had hooked up an antenna outside the building to show what the connection speeds were like. Even in heavy snow, he was still getting about 43 Mbps download speed, which is not far off from what I often get in my very connected Brooklyn apartment. Mason said the range of the current setup is about 6 miles.

The team’s radio tower is around 200 ft tall. But the whitespace radios are only about 100 ft up the tower due to current FCC regulations that forbid them from being placed any higher so as to not interfere with broadcast signals (even though there are no broadcasters in the area). Mason said the radio’s range could be extended if it were raised higher, and has petitioned Bergman to work with Congress to change the regulations.

The company brought me, along with the congressman and the others, to a house a few miles south of the community building. It looked like a standard, two-story suburban home, with a porch, space for multiple cars out front, and cute stonework adorning the windows. It belongs to Jason and Amy TenEyck, who have lived in the house for 18 years, along with their two kids.

The difference between this house and millions of others in the US is that it doesn’t have internet. Well, not really. The TenEycks used to pay an exorbitant amount of money, around $100, to get a small amount of internet from a satellite provider, which was unreliable at best, and capped their data each month. Amy said she bought their son an Xbox for Christmas, but they would have to drive to his grandmother’s house into Sault Ste. Marie—roughly 45 minutes round trip—to get internet to download game updates. The family had just one spot, near a window in the kitchen, with decent cell phone signal.

Kids in the area without internet would have to stay late at school to finish homework assignments that required web access. The TenEycks’ son told me that he uses Google’s Chromebook laptops at school, and his teachers use YouTube and Google Docs for quotidian classroom assignments. When the family was on their meagre satellite internet connection,the family would have to stop using the internet just so he could file his homework.

Days before Packerland paraded us through the TenEycks’ home, workers had installed its first consumer whitespace receiver in the country, which was beaming data to and from the tower a few miles up the road, through forest and snow. In that time, the family had joined Netflix, set up a Google Home speaker, and the kids started doing their homework at home. Now their son can download games at home, and he’s playing NBA 2K and Fortnite, just like millions of other kids in America. Amy uses WiFi calling, like FaceTime, to check up on her kids when she’s at work. She loves that she can now easily check in with her elderly mother, and her kids can connect with their cousins who live in New York state.

The family has joined the tens of millions of Americans for whom the internet is an extension of daily life. “Everything you need is on the internet,” Amy said. “Compared to what we had before, this is one thousand times better.”

Bergman told me that he wants tax credits for companies looking to build out solutions like Packerland’s, but realizes he may struggle in Congress to push for his constituents. “My challenge is that most of the representatives have easy access to the internet,” he said. He hopes to make his peers understand that the internet they take for granted is not a certainty everywhere in the US. Indeed, there are over 19 million people, around 6% of the population, who don’t have access to the internet at all. And Bergman doesn’t see this as a particularly divisive issue. “Rural America is not one party or another.” he added.

In Heigl’s home district, not far from Sault Ste. Marie, he said 38% of kids don’t currently have broadband internet access, and Jason Kronemeyer, the director of technology for the Eastern Upper Peninsula School District, who was part of the delegation at the TenEyck’s house, told me that 30% of the curriculum for the state of Michigan is now online. Some students have to drive three hours round trip to get to their school, and they can’t really afford to stay late to finish assignments online, or they won’t make it home when there’s a bus. Some teachers in the area are reluctant to make assignments that include any sort of media (like a YouTube link), as they know students’ internet connection might be too slow to load it. The internet, Kronemeyer said, is “a basic need for everyone in America.”

Heigl wants to set up digital literacy programs to ensure these families don’t get left behind. He wants to teach people what many take for granted, like how to buy things on Amazon, or set up a Facebook account. He wants to make sure these kids don’t trail behind their peers when they show up to college and haven’t been taught to study like their more connected classmates have. “We have to build the market, and show why the internet is important,” Heigl added, suggesting that families who have gone their whole lives without the internet might not know how necessary it will be for future success—the median age in the area is 53. “‘Build it and they will come’ doesn’t always work,” he added.

Packerland hopes to sell its service for $75 per month or less, on par with most consumer broadband offerings in more populated areas. It would take about 20 to 25 customers per antenna sector, Heigel said, to make that feasible. “It might be a little costly, it might be a little ugly, but we’re doing it,” Heigl said. “We’ve been challenging ourselves not to say no.” The service will be rolling out for customers more broadly over the next year, with the team working to extend its range and strength.

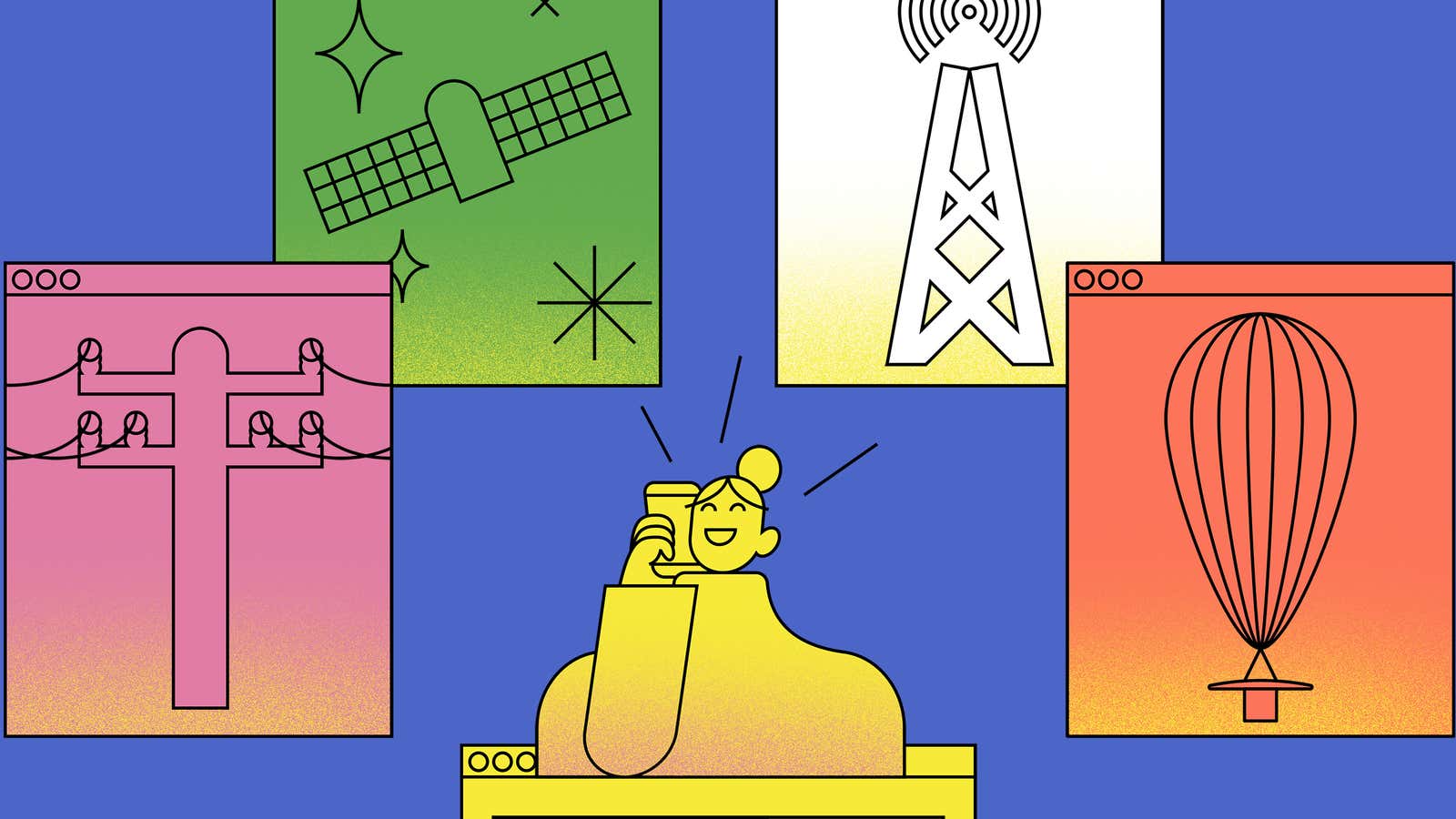

The TenEycks were the first ones to use this new technology in the US with Packerland, but they almost certainly won’t be the last. Still, it’s not a panacea. “There is no silver bullet, no one technology,” Mason said, that will solve the access problem for the entire world.

When the internet was envisioned, back when it was a way for US defense agencies and universities to talk to each other, data ran over phone lines. By the 1990s, dedicated fiber-optic cables were being laid across the country and under sea beds. They fed into local grids, usually made of copper wire that sent data to our houses and businesses. But telecom companies only undertook this costly process, of either digging up roads or adding to telephone poles, when there’s a dense-enough population of potential customers. This becomes even more of an issue when people live in particularly difficult areas to access, like mountainous forested regions.

In the US, one of the most prosperous countries on Earth, there are over 34 million people who don’t have access to broadband internet.

Although internet access has been proliferating around the globe, thanks partly to the falling costs of mobile phones and infrastructure, roughly half the world’s population still doesn’t have access to the internet, or around 3.4 billion people.

When you look at internet access beyond the US, the economics problem becomes even more stark: telecom companies are less likely to invest in networks in developing nations where people don’t have much disposable income. That’s why almost all of the countries in Africa have some of the slowest internet speeds in the world, followed by South America and parts of south Asia.

To create an internet where everyone has access, we’re going to have to think beyond the cable box. If we were restarting the internet today, how could we connect anyone? Could we do it if price were no object? What if we were trying to make it a business? Packerland isn’t the only company trying to pave the way to a world where everyone has access. Some ideas are simple, some even more radical than beaming internet over TV waves. Like balloons, as Alphabet is attempting with its Loon subsidiary.

“Broadband is the electricity of the 21st Century,” Shelley McKinley, the head of Microsoft’s corporate responsibility group, which includes the Airband initiative, told me. It’s what kids need to succeed in class, where tomorrow’s businesses will begin, and where the world communicates. She says that millions are unable to participate in the “new digital economy,” and while Microsoft has set ambitious targets in the US to bring more people online, her team recognizes that no one company or solution will close the gap.

But when asked whether it would be feasible to actually connect everyone in the world economically, McKinley is positive: “I absolutely believe so—if we get creative.”