by Roberto José Andrade Franco

November 12, 2018

It’s a Saturday morning at the edge of the state, close to where Texas, New Mexico and Mexico meet and blur. In the small town of Anthony, about 20 miles north of El Paso, houses have backyards measured in half acres, and the Franklin Mountains stand out on the horizon without the distraction of tall buildings. It’s the type of place where a yellow “Don’t Tread on Me” flag flies next to those of the United States and Mexico. On this hot July morning — after a breakfast of scrambled eggs, bacon, hash browns and menudo — 13 members of the 915 Pachucos y Pachucas Unidos begin their monthly meeting.

They gather around a large kitchen table. Yvonne Patino, the group’s president, starts by asking for receipts for recently made T-shirts and collecting each member’s $5 monthly dues. Seated to her left are Gracie Guzman and her husband, Victor, the hosts of this month’s meeting. Victor has slicked-back jet-black hair and an easy smile. As each guest arrives, he repeats the same question: “Did you have trouble getting here?” All answers reference GPS and the beauty of the area.

To Patino’s right is Frankie Herrera, whose baby-blue shirt and black pants are without a wrinkle. He always sports a hat and looks like he’s never worn sweatpants in his life. Asked if he’s the best-dressed person in his office, where he’s a medical support assistant for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Frankie answers, “Well, there’s a few others that are close.” Herrera and Patino, like many others here, are carrying on a family tradition. “My father, my great-grandfather, my uncles were pachucos,” Patino says. “My youngest son is a pachuco.”

With the meeting underway, Yvonne’s 6-year-old son plays with other children whose parents are members of the group. They are growing up around pachuquismo — a subculture that began in El Paso and whose hallmarks include a flamboyant style of dress; parties with swing dancing, retro music and vintage cars; and, more recently, community service. These men, women and children are sustaining a tradition that started in the 1930s. They also symbolize what’s distinct about the borderlands. Mexican Americans in El Paso have long straddled multiple worlds: Texas and New Mexico, Mexico and the United States, English and Spanish. The pachuco lifestyle celebrates these differences while passing on Chicano pride to the next generation.

–

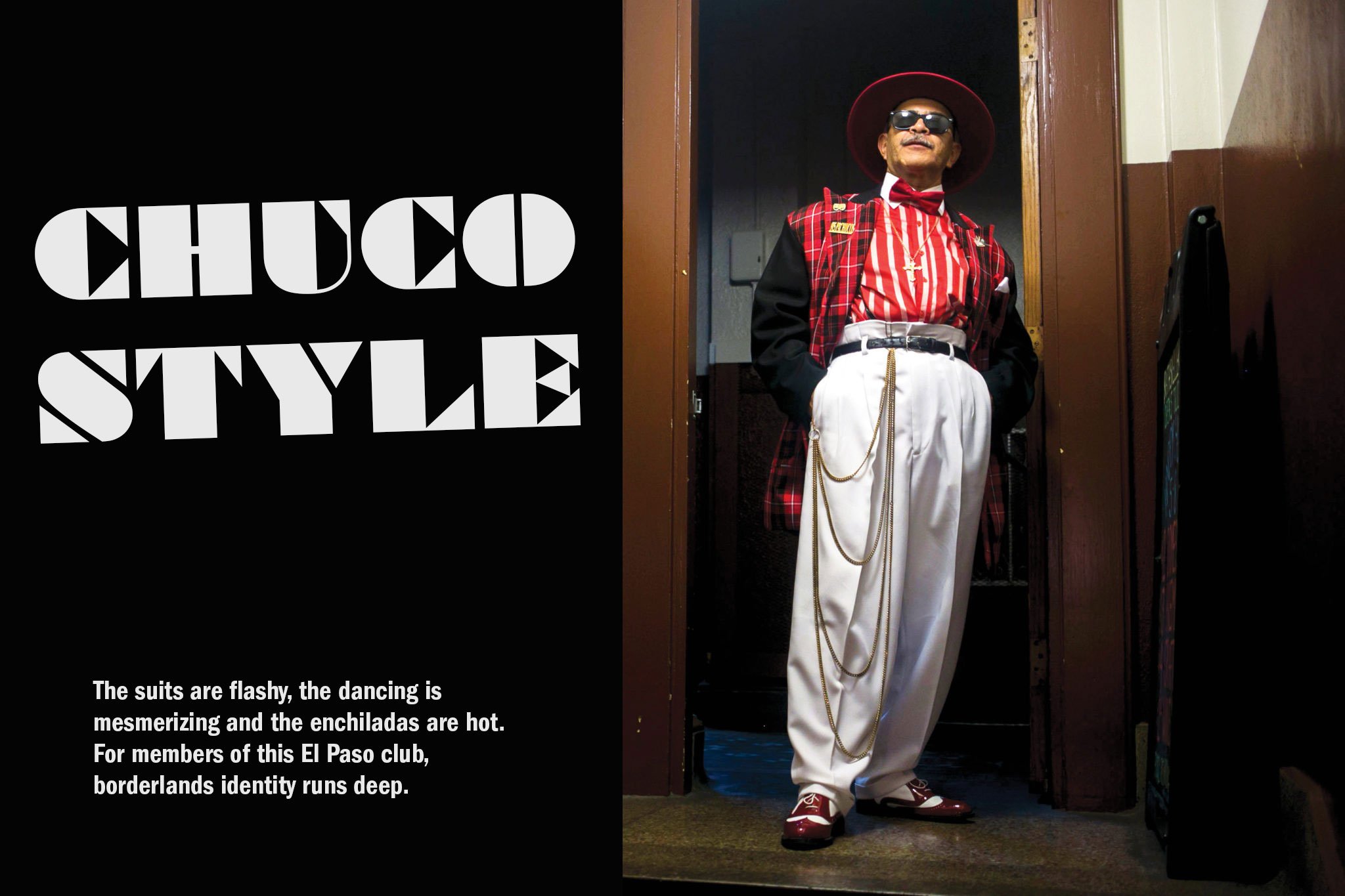

Pachucos are often thought to be gangsters or criminals. A 2017 story by a Los Angeles television station had the telling headline “Pachucos: Not Just Mexican-American Males or Juvenile Delinquents.” In fact, the first pachucos weren’t usually gangsters, but rather Mexican and Mexican-American teenagers and 20-somethings who developed their own style in the 1930s and ’40s. The subculture originated in the El Paso-Juárez area and spread westward with migration. Zoot suits, or tacuches, have always been the most distinguishing feature. Adapted from 1920s African-American jazz scene attire, tacuches come in loud colors and patterns. Bright yellow, sky blue or blood red aren’t unusual; neither are pinstriped or checkerboard patterns.

Traditionally, pachucos wear double- or triple-pleated high-waisted pants. Accessories include a silver or gold cadena, or chain, that loops down over the baggy leg and hangs a few inches above the ankle. Also common are vests, gafas (glasses), resortes (suspenders) and a long, multicolored feather tucked into the band around a tandito, a hat. Add some tablitas — shiny, colorful shoes, often in two tones — and you have the standard pachuco uniform for men. Women can wear a zoot suit, baggy pants with suspenders or simply a jacket with a long, tight-fitting skirt. Beyond the style of dress, pachucos talk in a slang, or caló, closely related to the Spanglish spoken along the Texas-Mexico border.

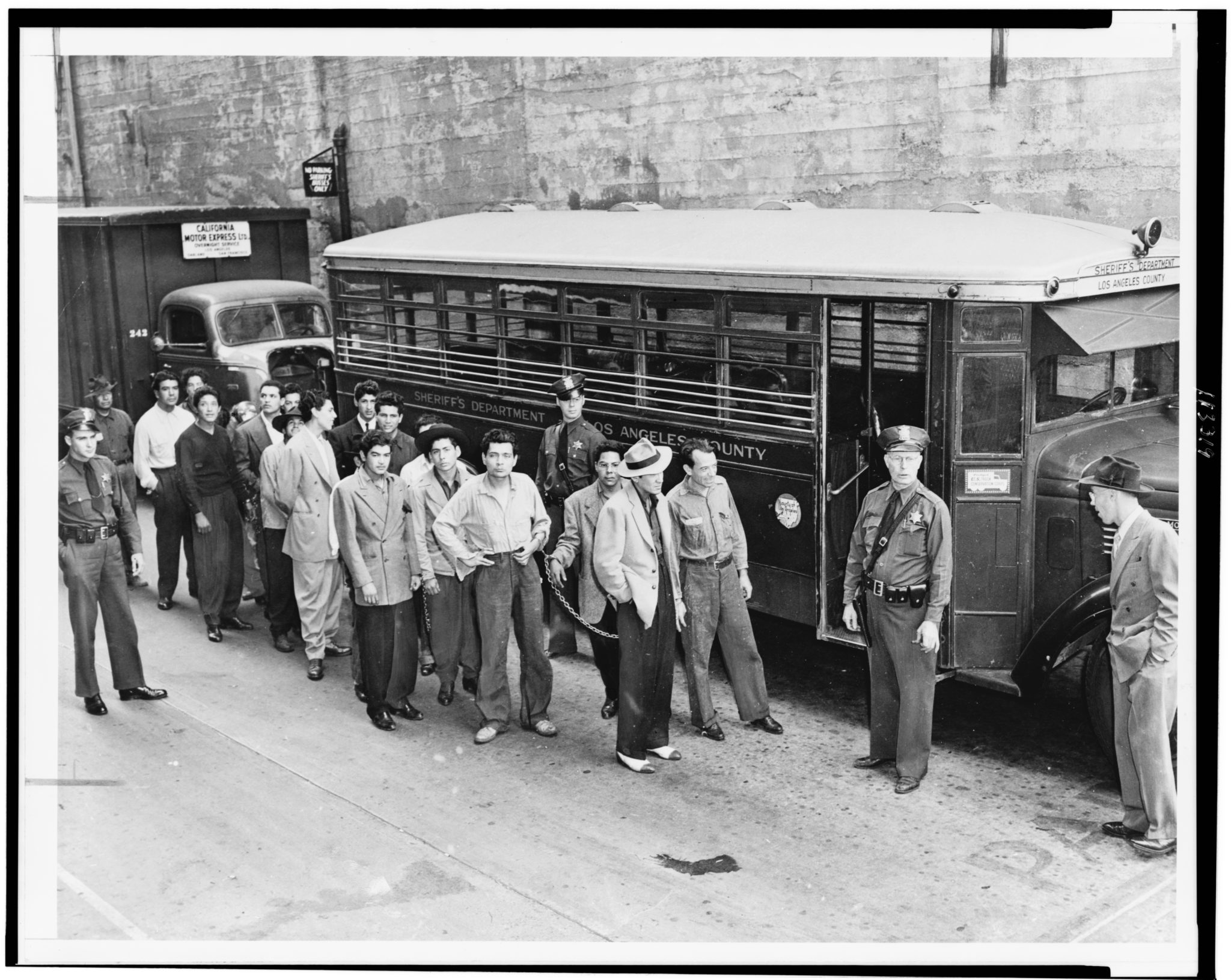

Pachucos are best remembered for the Zoot Suit Riots of 1943. Over several nights in early June, in downtown Los Angeles, sailors stationed at a nearby base attacked anyone who wore a tacuche. Amid the jingoism of World War II — legislation leading to the internment of Japanese Americans was passed less than two years before the riots — pachucos aroused fears that they were unable or, worse, unwilling to assimilate. Oversized and baggy tacuches were also deemed a direct affront to the War Production Board’s clothing regulations, which aimed to conserve fabric. This all fed into the tensions that culminated in the Zoot Suit Riots. But even that name is misleading, as it places the responsibility on those who wore tacuches.

“Perhaps it’s time to revise that narrative,” says Ruben A. Arellano, a historian at the University of Texas at El Paso. “Instead of perpetuating the myth that it was [pachucos] who were responsible for the riots, we should call it what it actually was, which was the Sailor Riot. Because it was the young sailors who were out in caravans and carpools and sometimes even assisted by the local authorities to go out and beat up and strip these young Mexican Americans of their zoot suits.”

The caravans Arellano refers to are what Carey McWilliams called taxicab brigades. McWilliams, an activist and journalist who covered the riots, described the sailors as traveling in groups of at least 20 cabs. When they spotted anyone wearing a zoot suit, they jumped out and beat him up. “The sailors then piled back into the cabs and the caravan resumed its way until the next zoot-suiter was sighted, whereupon the same procedure was repeated,” McWilliams later wrote.

Because of the riots, there’s an assumption that pachucos were from Los Angeles. The belief that they’re gangsters also persists. These are misconceptions the 915 Pachucos (whose name references the El Paso area code) are trying to change. “We educate our youngsters about the culture,” says Patino. “Some of them still have this image of us being cholos, and that’s not what we’re about.”

The El Paso group is a nonprofit that has donated Thanksgiving meals to the hungry, Christmas toys for children and food for the homeless, among other efforts. Members have spoken in history classes at area colleges and raised money for families who can’t cover medical or burial expenses. Pachucos y Pachucas Unidos continues to expand, with chapters in Tijuana, Los Angeles and Las Vegas, among other cities.

Pachucos have long evoked consternation on the southern side of the border as well as in the United States. Mexico’s northernmost states have long felt the geographic and cultural distance from the central parts of the country, in particular Mexico City. Pachucos — and Mexican Americans as a whole — were even more outcast.

“The pachuco has lost his whole inheritance: language, religion, customs, beliefs,” argued Octavio Paz in The Labyrinth of Solitude. “His disguise is a protection, but it also differentiates and isolates him: It both hides him and points him out.”

Other Mexican intellectuals — José Revueltas, Carlos Monsiváis, Salvador Novo and José Vasconcelos, to name a few — also noted the precarious position pachucos occupied. They weren’t quite Mexican but clearly neither were they fully American. This is a tension that never ceases.

For Victor Guzman, the memory of a trip he made in the late ’90s to Camargo, Chihuahua, about six hours south of El Paso, still stings. “I was wearing my pants, all the way up to my belly button. I had suspenders, I had my hat on,” he says, “and I would get a lot of bullshit: ‘You guys are all pinche gabachos. You guys think you’re all that.’ And that’s not the case.”

–

At Lincoln Park in south-central El Paso, the lawn is shaded by a tangle of highway overpasses. One route connects the city to the rest of Texas, another leads to New Mexico and a third goes south to the international bridge with Juárez. Dozens of formerly drab highway pillars are emblazoned with colorful murals. There’s John F. Kennedy, a bald eagle, Cesar Chavez, and the black eagle that began as the United Farm Workers’ symbol and is now synonymous with the Chicano movement. Another painting shows a pachuco with his hand in his pockets, leaning back. Nearby, there’s a pachuca in a sleeveless shirt and suspenders. She holds an American flag in her right hand, while her left arm is draped with a Mexican flag.

The park is home to many of the El Paso pachucos’ public events, where curious onlookers often stare and ask questions. “I know we attract a lot of attention because of the way we dress,” says Victor Guzman. “But attention is not really the main thing. It’s us enjoying ourselves, being together with people that, that…” As he struggles to find the right words, Gracie finishes his sentence: “That enjoy the culture. And respect the culture.”

Members often pose for pictures in exchange for donations to whatever cause they’re there to support. They dance to music by the likes of Cab Calloway, Tommy Dorsey, Pérez Prado and Glenn Miller. “You can’t go wrong with oldies,” says Victor. When they dance, people gather around to watch the impressive sight. The tacuche’s bright colors and patterns make kicks and dips stand out, and the chain hanging from a pachuco’s waist glints while he moves.

I couldn’t help noticing that most members of the El Paso group were in their 40s or older. They speak often of passing the tradition on to their kids, many of whom tag along to events, but will it stick? Matthew San Roman, 27, is a sort of freelance pachuco, unaffiliated with the 915 group, who says he rarely meets other young pachucos. A Chicano studies major at the University of Texas at El Paso, he wears his tacuche most days. When classmates ask questions, San Roman sees an opportunity to start a conversation on Mexican-American history. “I get all kinds of reactions,” he says. “I really want them to know [about pachucos] because it’s part of them too.”

One hopeful sign: Back at the monthly meeting, conversation turns to an upcoming trip to San Antonio, where the El Paso pachucos are helping to start a new chapter. All 13 members will make the eight-hour drive to meet like-minded folks in “San Anto,” as they call it. They’ll sell enchilada plates and T-shirts to pay for a rental van, and then they’ll gather at a bar. Yvonne tells everyone to bring their two best tacuches. “Los mero mero, mas chingón,” she says — roughly translated to “the most badass.” They all laugh but know exactly what she means. Everyone here takes the symbolism of the tacuche seriously.

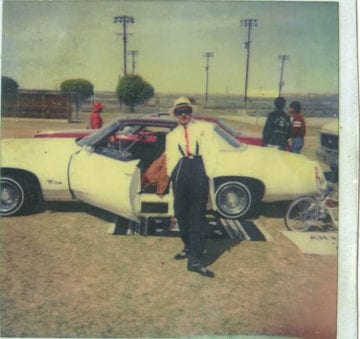

“My first suit, I bought it when I was 16,” Victor tells me. “I was so proud, man. I was wearing that thing to high school, I would only wear to las quinceañeras, las bodas. At that time, I was 16 so I couldn’t go to any bars or anything, so before that, I would only wear my pants, my suspenders, my tie, my little tandito, unas tablitas que me dio mi abuelito. But I loved it.”

Pachucos tend to remember the first time they wore a tacuche. “I’ve been dressing like this since I was 13,” says Frankie, now 53. “In 1982 and 1983, guys from California would come in and compete for the zoot suit contest. Those two years, I got first place. They couldn’t beat me and they would get all mad … because they thought the pachucos were from over there.”

But pachucos come from El Paso. The city’s semi-official nickname, after all, is El Chuco. According to lore, when someone asked traveling Mexican laborers their destination, they’d respond, “P’al Chuco.” To El Chuco. This westernmost edge of Texas that’s much more like Juárez than it is like Austin. Where a wall clearly marks the political borders but the cultural ones continue influencing each other.

Near the end of the meeting, members recap everything they’ve discussed. Someone quietly translates for the members from Juárez — la familia Pérez, as they’re referred to — who cross the border to attend meetings and any planned events.

“José ya no va poder brincar” — José will no longer be able to cross — Francisco, the father of la familia Pérez, says of his young son. His visa will expire around the same time as the San Antonio event. Its renewal is already in process but “con todo lo que está pasando,” it could take months. Members offer their help in any way they can. “We look out for each other,” says Yvonne. “Gracias,” Francisco answers.

For now, the group’s focus is on founding more chapters. Asked if these will expand beyond the Southwest, Yvonne nods. “That’s our goal, to extend as far as we can nationwide, and keep going,” she says. “It’s something we love to do, it’s in our roots and hopefully our younger generation … they will carry on the legacy of the pachuco.”