1. The announcer

Stood in his traditional place, at the back of the main spectator stand, radio microphone in pocket, Liam Hickey allowed himself a private and deeply felt “Yes-s-s” before announcing the final score. His voice echoed tinnily from loudspeakers around the ground. The home team, Dulwich Hamlet, had won 3-2. A couple of months into the new football season, on a blowy afternoon in October 2017, it was enough to put them second in their league. Hickey thanked the 2,000 spectators for coming, and urged everyone to return for Dulwich’s next home fixture in a fortnight. The announcer had no clue how different the club’s fortunes would look two weeks later, nor how dramatically his role there was about to change.

Hickey had been devoted to this modest south London side, lodged forever in one of the bottom-most reaches of the English game, since he was seven, when a misstruck shot came bazooka-ing past the post to flatten him, personally, in the stands. (Love had budded by the time a team doctor revived him with smelling salts.) Now 54 and a crimson-cheeked business analyst who drove in for matches from Kent, he was still waiting to see Dulwich win their way into a higher tier of football. Hickey had some time ago formulated the sentence he would deliver should the splendid moment ever come, that “after 107 years … after 108 years … after 109 years … Dulwich Hamlet are finally out of the seventh tier!” They almost managed it a season ago, “after 110 years”. But on the final day, Dulwich were rubbish.

Hickey didn’t only announce the scores. Mostly by accident, over time he’d taken on a diverse portfolio of jobs at Dulwich. For a while he sought out sponsors, and before that he cared for the players’ distinctive pink-and-blue kits. At one stage, Hickey scurried around pitchside with the substitutes’ board, only resigning that assignment after a row with a coach (now long gone) came near to blows. He chaired a committee of volunteers who gave up hours every week, out of love, just as he did.

Days after the 3-2 victory in October 2017, Hickey received a phone call from Dulwich Hamlet’s owner, a man called Nick McCormack, who sounded panicky. McCormack wanted to know if Hickey would step up – whether, in fact, Hickey would take over everything: fixtures, figures, the future of the club. “We were in trouble,” McCormack recalled. “I needed some help.”

McCormack, a Bromley-based businessman and an increasingly distant and dismal steward of Dulwich Hamlet, was in a fix. Years earlier, strapped for cash, he had agreed to sell the club’s south London home, a low, boxy stadium called Champion Hill. Champion Hill had since come into the possession of property developers who had ambitious plans for it; plans that would refresh the facilities but also shunt the pitch over, making room for new-build homes.

These plans had come crashing up against an obstinate local council. Neither side wanted to budge, and Dulwich Hamlet was stuck between them – with one added wrinkle, McCormack confessed. Back in 2014, when property developers first came along, he had handed the day-to-day running of his club over to them. He didn’t have the time any more, he said, or the money. The developers were backed by private equity. They had deep pockets, and they helped pay the players’ wages. Dulwich, by signing a new licence with the developers, could keep playing at Champion Hill. The club’s debts disappeared. It was an extraordinary arrangement, and even a matchday announcer could see that the situation risked ending unhappily.

And now, it had. On the phone, McCormack explained to Hickey that with their stadium plans in limbo, the developers had decided to switch off the money. They would step away and stop processing payments on 1 November. Hickey checked: a week’s time. There would be six months to get through after that, till the season concluded in May. The club generated a good amount of money from ticket sales, and fans certainly drank a lot of beer during games; but when Hickey opened up the books he could see at a glance that the cash reserves were low. Soon he would learn that a substantial quarterly VAT bill was due to be paid, also that an HMRC investigation was under way into previously underpaid tax.

The club looked close to the brink already, and would get closer. Over the rest of the season, Dulwich would have to fight for permission to play at their home stadium, for the right to bear their own name, for the chance to battle for promotion. This was not an impressive club, but it was impressively ancient: founded by a Victorian, it had released the better part of the first team to fight on the western front, and later lent its stadium for matches at the 1948 Olympics. Over generations, Dulwich Hamlet had come to represent a certain low-watt resilience, and a self-deprecatory wit about that pink kit. To many people the club simply meant “dad”. Hickey had been brought here by his father. And he could not countenance letting this old club – his father’s club – die. He told McCormack: “Leave it with me.”

2. The nouveaux

Even before considering seats, and stands, a football pitch in a city assumes at least 1,000 square metres of precious floor. At large, thriving clubs (Arsenal, Chelsea and Spurs in London, City and United in Manchester), a desire to expand a home stadium gets checked, usually, by surrounding dwellings. People’s houses cannot be annexed, so facilities are manipulated upwards, expensively, or relocated. The trouble for smaller, less prosperous clubs tends to be that, before long, someone will want to build dwellings on the pitch. This has happened in Hendon, Torquay, Kettering, Newbury, Northampton. In East Thurrock, where an overlooked pitch suddenly rocketed in value because of a government regeneration scheme, the family who had teamed up to buy and save the club turned on each other and went to court over the rights to develop.

On the site of Dulwich Hamlet’s stadium, they used to play croquet. Football came in 1902, and a new pitch was laid between the wars. This was torn up and replanted in the 1950s, then built up in the 1990s to comprise a breeze-block clubhouse and a concrete grandstand. Surrounding the pitch, which is laid out so that one corner cuts into a hill that gently rises towards Camberwell and Peckham, there’s a screen of anti-bird mesh and beyond that a Sainsbury’s, a dog-walking park and a dilapidated field of peeling astroturf. One local resident, Catherine Rose, had walked past this ugly stadium a thousand times before ever going in. One afternoon in 2014, she was invited to a community consultation event arranged by the developers who’d just acquired the site. She listened carefully while a bombastic executive explained what might be done. Dulwich’s pitch could rotate, shunt west – on to that rundown astroturf – leaving room for stacks of new dwellings. The developers, who’d bought the site for £5.75m, stood to make a substantial profit should their plans work out, perhaps £70m or £80m.

Rose had a young son and was cheered to learn that if Champion Hill was smartened up, schoolchildren would be allowed in to use the better amenities. The developers insisted that a proportion of the new dwellings – they intended to make 155 – would be affordable. “They basically promised Christmas,” Rose recalled. Back then, the developers were called Hadley Property Group. Later they became Meadow Residential. The stadium itself was registered under the ownership of a different company in the Isle of Man. In Delaware in the US, another company had been set up with an interest in Dulwich Hamlet’s intellectual property. All these companies could be tracked back to the controlling hand of a private equity firm with offices in London and New York, called Meadow Partners.

Towards the end of the community consultation in 2014, Rose noticed that fans in pink-and-blue were streaming into the stadium, about 700 of them scattering around the concrete grandstand or wandering out to lean against the barriers behind the goals. Dulwich were about to play against Kingstonian FC. She stayed to watch. After 90 minutes – the smell of whisked-up turf, a heartstopping nearness to the players, the parping voice of an announcer confirming a win – Rose was captivated. She’d watched Premier League games on telly, but nothing like this.

Imagine for a moment that all the clubs in all the divisions of English football live inside one building. (A nice tall place, one of those multi-use blocks that flush developers love to erect.) The summiteers of the Premier League – they’re up in the penthouses, where it’s loft-style living, all memory foam and megaviews. A floor below, the nearly-men of the second division take up the nicer apartments, jockeying to be closest to the executive elevator. Underneath them, the third-division lot are in help-to-buys, the fourth division in dormitory bunks. A steeply descending staircase to the ground floor marks the point at which elite, professional “league” football ends, becoming the more sprawling, regional, semi-professional “non-league” tiers. Down these stairs they’ve had to open up the lobby, add lean-tos, to accommodate everyone. The players of the fifth tier sleep on mezzanine couches, while those from the sixth tier lie on mats where they can. In the cellar (closer to the warrens of scratch leagues, pub derbies, prison friendlies), Dulwich Hamlet hunkers down with the rest of the seventh tier.

Others have made their way up and down the floors over time, but not Dulwich. They’ve been down here in the dark since the place was built. But at least it’s warm, collegiate. Descend this teeming new-build from penthouse to cellar and you may find more to like the further you go. People appreciate non-league football for what it isn’t – smug, slick, pampered. Down here the competitions get named for apple liqueur, bottled butane, dehumidifiers; there’s a Toolstation League and a Vanarama League. Fans who take the train to away games know to give their star player, riding in the same carriage, his privacy.

Dulwich’s seventh-tier league is sponsored by a company that makes glue and patio grout. Certain traditions would be unworkable at grander levels of the game, not least the adorable moment at half-time when rival supporters pootle past one another, swapping ends, in order to always be behind the goal their strikers will target. Inside the more palatial stadiums of the Premier League, there’s no chance Dulwich fans would get close enough to distract an away-team goalie the way they like to – by reading back to him, for 90 minutes, his old Facebook posts. Gutted you missed that parcel, mate.

Real intimacy, a special understanding, can exist over the pitchside barriers at grounds such as Champion Hill. When Rose first came, she was in her early 40s, in a rut in her life. Off the career ladder, struggling for confidence. But watching Dulwich Hamlet’s players sweat it out against Kingstonian, “many of them discarded by bigger clubs, journeymen who felt they might have missed their time, their opportunity”, touched her deeply. After that first game she returned again and again, bringing her eight-year-old son, and between them they hardly missed another home fixture.

At the time, hundreds of non-traditional fans like Rose were finding their way to Dulwich. Self-described club “dinosaurs” like Hickey watched as the crowd around them grew from an average of 150 a week to 700. Around the little stadium, south London was restlessly gentrifying. Young professionals showed up, the weekend curious, hungover millennials after nights out in Peckham. The dinosaurs looked on with frank, ungrudging fascination as these latterday fans – Hickey referred to them as “the nouveaux” – fell head over heels too. Something unusual was happening – a younger, liberal outlook bleeding into the usual sporting tribalism, so that the terraces started policing themselves of a common blight (racism, homophobia, misogyny), which in turn encouraged more casual attendees. Gates kept rising, with crowds at some games pushing up to the ground’s 3,000 cap. As one fan described it, Dulwich offered “a beers-in-the-air intensity, minus the toxic shit that normally goes with it”.

Rose, now part of the tribe, began to regain her nerve. Feeling more plugged in to the community, she decided to run for the local council. In May 2016, she was elected to be a councillor for Southwark, which includes Champion Hill. As it happened, that spring, Meadow’s redevelopment bid had just ramped up, and it came before Southwark’s planning department. Meadow believed the scheme would get the council’s blessing, because they had once received a “broadly supportive” letter from Southwark. The leader of the council, Peter John, told me Meadow should have known not to expect any such blessing because he’d told them there were fundamental flaws with their bid at the outset.

The application became a shambles. The council sat on it. Meadow appealed. The problem was the rundown field of astroturf, west of the stadium, crucial to Meadow if it was to be able to build at the scale intended. This astroturf was council land. It had been leased to the football club for some time and was about to return to council ownership. “We wanted to get it back for the community,” John told me. Meadow felt this to be political posturing, timed to impress residents before an election.

A legal action was launched. When the appeal came to court in London on 16 October 2017, the hearing sputtered to another stalemate. In John’s view, it was on that day that Meadow “chose, I think, to behave in a really aggressive and unfriendly fashion towards the football club”. Meadow felt it was Southwark council that put Dulwich Hamlet in harm’s way, by thwarting a rebuild that would benefit both the developers and the club.

It was the following week that Hickey found out responsibility for Dulwich Hamlet was tumbling his way. The announcer had formed a bond with Dulwich’s head coach, Gav Rose, a 39-year-old who grew up locally; and it was from Gav Rose (no relation to Catherine) that Hickey learned what was needed in terms of salaries: about £20,000 a month. During the final days of October 2017 he exchanged emails frantically with Meadow, trying to catch up and crash-learn the intricate operational detail that would give him a shot at keeping the club going after 1 November.

Could it be right that Meadow would continue to take the profits from the matchday bars? Why was Dulwich’s licence to play games at Champion Hill due to expire not in May, when the season ended, but weeks earlier, in March? If this licence were not corrected in time, it could have miserable consequences. Dulwich could win their way to promotion, after a soggy century’s wait, and then be held down on a technicality. A Meadow rep told Hickey: “This is with the investment committee.”

Shortly afterwards, six days into Hickey’s tenure, Meadow issued a gloomy statement about the club’s probable future. This was “a very difficult situation”, Meadow wrote. But “substantial funds” had been poured in already, and until it had the support of Southwark council to develop the site and recover its money, Meadow’s investors would permit no more. It concluded: “Without Meadow’s funding [Dulwich Hamlet] will be forced to close in the near future.”

Hickey was managing not to panic. In mid-November he was buoyed by a home win, happy to be responsible for nothing more than a microphone for 90 minutes. Dulwich had won five in a row and were top. During the game, some of the younger fans had started chanting about Meadow. They were itching to take the fight to the developers, to the council, to somebody. There was an inclination to chippiness that many of the nouveaux fans displayed. They seemed energised by the conflict. Hickey guessed they knew more about things like social media than he did. Perhaps that could be put to use. Hickey, thinking about it, decided he’d go and recruit himself a nouveau.

3. The changing room

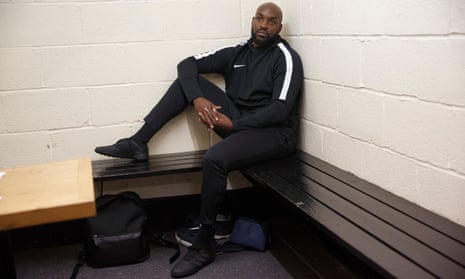

So this was seventh-tier football. Reise Allassani, the team’s newest signing, slighter than average in the Dulwich changing room – 5ft 6in and willowy – had been given a one-size shirt like everybody else, and it hung down around him like a smock. Already his teammates loved to watch Allassani sprint and swerve in that big, fluttery kit. Twenty-one, with shoulder-length dreadlocks bleached ochre at their tips, Allassani was once a trainee of real promise at a Premier League club, before injury sent him falling down the divisions. Fit again, he’d come to Dulwich to play, a full season of about 30 games, he reckoned, to jump-start his career. In the first game of Hickey’s tenure, in early November, he feinted left – no, right! And, fluttering in pink, he struck from distance, scoring the game’s only goal.

Dulwich had pulled clear of their closest rival, Billericay Town, in the standings. Changing-room rumour about Billericay was that they had a monthly wage bill of £80,000, making them the league’s best-funded side. Changing-room rumour about Dulwich was that they might be bankrupt by Christmas. Allassani had read the gossip online like everybody else. He wrote it off as talk. Dulwich’s captain, veteran Kenny Beaney, even cracked jokes. “What are they going to do,” Beaney ribbed his younger teammates, “put a lock on the gate; stop us playing here?” In fact Beaney had been unnerved by the same rumours himself. One day he took his coach aside. “The boys are reading about it,” Beaney told Gav Rose. “They’re wondering, are they gonna have a job?”

Beaney used to lean on the barrier as a boy and watch Gav Rose play for the team. When Gav Rose graduated to become a coach, and founded a local youth academy, he trained Beaney up to be a commanding player for Dulwich Hamlet. There were maybe 100 spectators who paid to watch back then. As the wages in lower-league football tend to be indexed to gate income, Beaney’s salary in those days was £50 a week (petrol money). He was a scaffolder, contracted to work around the changing neighbourhood as new-build and home extensions went up. Beaney’s part-time footballing took him to other places, other teams, but after about a decade he returned to Dulwich. By now the attendances had boomed and salaries had gone up accordingly, to an average of £300 a week (mortgage-payment money). Working in construction, Beaney could appreciate the irony of Dulwich’s situation: the same gentrification wave that had super-sized crowds, putting the club in a position to finally climb the leagues, had also made 1,000 sq m of undeveloped land look irresistible to those who would build.

Before a night game that November, Gav Rose gathered the team in the changing room. He confirmed what they knew: Dulwich was in a pinch. By his own admission a hothead when he started out in management, but now reformed, the coach spoke calmly. He told his players to keep their composure and to keep playing their football. He had never cheated them of a pay cheque and, he swore, he never would. Hickey supported him in this. “The first time we don’t pay the players,” Hickey had admitted to Gav Rose, “the fight’s over.”

Everything at Dulwich was already offered out for sponsorship: the curved glass on the dugout huts, the pitchside “toilets opposite” sign. Meadow would not relinquish bar profits from games, on the order, Hickey was told, of its investment committee. (Meadow pointed out that as it owned the stadium, and the bars within the stadium, it had no obligation here.) So Hickey made a decision to put aside pride, and put out buckets. More than £2,500 was raised at one game, and 20 times that over the season to come. “Our job is to keep winning,” Gav Rose told his players. “And if you can’t win, show the supporters that you’re giving every last bit, so that they do. You guys now are a symbol of a club in a bigger way than you’ll ever be again.”

The coach considered his young star, Allassani, in the middle of all this. “He’s probably sitting there thinking, ‘I know I’m at a non-league club – but what is going on?’” In fact, Allassani was realising what reserves of love he had for the game. It was only by coming to play here, Allassani said, that he realised how much he wanted it. In a game against against Metropolitan Police FC, he dribbled through a clump of beguiled opponents to score from miles out. Four minutes later he scored another, after which he skidded on his knees toward the rusted pitchside barrier as if this were Wembley, not an away game at a leisure centre off the A309.

Allassani was starting to look like an athlete whom it was unjust to field at this level, and on New Year’s Day he scored a hat-trick to mark the halfway stage of his comeback season. Teams that did not want to wait till May approached Gav Rose to see about buying Allassani and taking him back up through the divisions immediately. Selling would ease Dulwich’s financial woes. But there was promotion to consider, with Billericay right behind them in the standings. Everyone in the changing room badly wanted to make that little bit of history by winning – like all footballers they ached for up. At the same time, they sympathised with Allassani, because who knew if the offers would still be there after the season, or if he’d still be fit. Gav Rose took a risk and clung on to his star.

The team slumped: losing three in a row. Met Police FC came back to Champion Hill and held on for nil-nil. Allassani wasn’t scoring so regularly. Dulwich didn’t win for a month, then two.

By March, Dulwich were plunging in the standings. When Gav Rose watched his guys lumber into the away team changing room before a March game against their great rivals, Billericay, he guessed the distracting swirl had finally overwhelmed them. You could hear the Billericay fans outside, tallying Dulwich’s woes in song. The pitch was horrible that night – lines painted on mud. Billericay scored inside 10 minutes. When Dulwich equalised, they started to play a bit, even thrilling in the old way. Allassani was flitting, fluttering. Then the ball spun awkwardly in front of Billericay’s goal. He stretched for it in the mud and fell, twisting. The first physio to reach him turned to Gav Rose in the dugout, making the expansive, dreaded gesture: stretcher.

4. The fan and the partner

Behind the away team goal a fan called Tom Cullen watched as Allassani was carried away. He rarely stayed in one place during games, this twitchy, bearded 28-year-old: nerves. Prowling near the barriers, Cullen caught the attention of an assistant coach and asked after Allassani. “Was it the neck?”

“Ribs.”

Cullen went back to his mates behind the goal. “Ribs,” he reported. A proud nouveau who wore a sun-bleached pink cap to games, Cullen worked as a contractor at an animation studio. For fun, initially, he’d agreed to run Dulwich’s Twitter account. Then, when conflict engulfed the club and Hickey appealed for help, Cullen chose not to renew his contract at work – telling himself he’d take a month off to help. That month became five. By March, Cullen still had not returned to his old job. Instead he had taken on the scrappy, guerrilla work of trying to provoke Meadow and the council out of their impasse. Hickey and Gav Rose would later wonder where he came from, this random fan with the social-media passwords and a knack for weaponising small resources.

On 23 November there was a summit with Meadow’s reps. Cullen pitched an idea to Meadow: share with the club the disputed bar money, and in return they’d help talk the council round. Possibly this offer was not appreciated. Four days later, an email came from Meadow that raised the prospect of Dulwich paying back rent to cover the years since Meadow bought Champion Hill in 2014. Owner McCormack – hands-off, hopeless – told me he’d always wondered if and when such a bill would appear. “At the end of the day, they were our landlords, and they weren’t charging us rent to play there.” The itemised bill, when it landed in Hickey’s inbox, added up three-and-a-bit seasons of utilities, cleaning costs and other fees, topping £120,000. At the time Hickey was struggling to meet the monthly payroll of £20,000, and pooling funds, moreover, to settle a similar bill for underpaid tax.

Things got worse. Shortly after the email about the back rent, Meadow sent a revised licence to play at Champion Hill. This licence would run until the end of the season, but it included stipulations, Hickey said, that he did not agree with. While the club sought legal advice, Meadow followed up by email on 6 December: “If this is not signed by Thursday lunchtime, we will not [...] let the football club enter the premises at the weekend.” Brightlingsea Regent were due on the Saturday, and 2,000-odd fans. With the beer money out of reach, the club needed the income of a large Saturday gate. They signed.

Afterwards, Cullen suggested publicising the struggle with Meadow to put pressure on the developers. He wrote on the club’s Twitter account that the revised licence was signed “under duress”, and his criticism of Meadow became more direct. In February 2018, at another meeting with Meadow reps over the bar profits, there was irritable sparring. “You’ve already thrown the ‘big evil development’ narrative out there,” a rep said to Cullen, according to two people who were at the meeting. “What more can you do?”

Cullen said: “Let’s find out.” He was convinced that when Meadow spoke of its “investment committee”, what was really meant was one man, a senior partner, an American called Andrew McDaniel. He had a home in London and oversaw Meadow’s European acquisitions. McDaniel had made a brief appearance on a BBC news programme in the autumn, to argue the case for the Champion Hill rebuild, but hardly anybody inside the club had met him. Cullen, by now, had spent weeks diving in among construction lore. He’d come to think it a shame that when cities were asked to surrender something for new dwellings – a pub, a church, a row of shops, a football pitch – however super-visible or sore the alterations, the people pushing it through were permitted to stay in the background.

Cullen started emailing McDaniel directly. “You’ve underestimated our leverage,” the Twitter guy wrote to the senior partner. He fed a story to the Independent, revealing that McDaniel was not the only magnifico with an interest in Dulwich. A housing group called Legacy, founded by footballers who’d grown up locally, including the ex-Manchester United player Rio Ferdinand, had offered Meadow around £10m to sell the contested site and walk away. (Ferdinand is a childhood friend of Gav Rose.) That was back in the autumn, and Meadow said no; but knowledge of the offer undermined the view, long pressed, that without Meadow’s investment and goodwill, Dulwich hadn’t a hope.

It was a little victory for Cullen. Then he misstepped. Using the club’s Twitter account, he uploaded a photograph of McDaniel, and included a goading message to the effect that it would be a shame were this enigmatic American to have his image widely shared. The internet, so provoked, did what it does, and for a day or two low-flying memes about McDaniel went around. “We had an understanding that this didn’t go down very well,” Gav Rose told me.

I contacted McDaniel to request an interview, and was turned down. But Meadow invited me to the company’s London office to sit down with a publicist and a lawyer, to hear Meadow’s side of the story. It was agreed the meeting would be off the record, and McDaniel would not be joining us. We had just sat down in a conference room when the sliding door came off its runners and wouldn’t budge. After various suits from the office had failed to free us, a sandy-haired, baby-faced man in his late 30s stepped in, squatted and heaved aside the whole fixture. Sprinkled with ceiling dust, he held out a hand – “Andrew McDaniel” – and left.

It was hard to square this boyish office-chevalier with the man who’d become an ogre to much of south London. I did not get a chance to ask him how he felt about that. Meadow said it would only communicate on the record via email, and my subsequent list of questions went unanswered, barring a few more bromides from the publicist.

After the Twitter episode with the photograph, word reached the club that Meadow had repeated its threat to evict, even though Cullen deleted the picture. “The feeling seemed to be these were personal attacks,” Cullen said. “But these sort of actions were personal attacks on thousands of people. There are people who have nothing else other than Dulwich Hamlet. This. Is. Their. Life.”

A day before the muddy Billericay game in early March, Cullen, Hickey and Gav Rose were preparing for the worst by visiting other venues, kicking turf, testing sightlines, trying to imagine this or that borrowed ground as home. During the Billericay match itself, the rival fans were merciless, as rival fans will be when they’re 1-0 up. You’re homeless. And you’re losing. Towards the end of that game Dulwich somehow turned things around, 1-1, 1-2, 1-3. Their fans were merciless in turn. We’re homeless. And we beat you. The result put Dulwich above Billericay in the league – back on top.

5. The mayor

Catherine Rose had heard about threats to evict, and the struggle over beer money. She was visiting Westminster, to advocate on behalf of her club, when she learned that Dulwich Hamlet were now being asked – wait, what? – to surrender their own name.

Word came through to her at midday on 6 March. Hickey had that morning received the legal letter on his doorstep. It came from solicitors for Meadow’s Delaware-registered company. Trademark on the name “Dulwich Hamlet” had never been secured by McCormack or any of the club’s previous owners. Now it had been secured, by Meadow. Dulwich were no longer to use their own name in any printed literature or online communications, said the letter. When they dug through recent issues of the Trade Marks Journal, there it was – between registrations of the phrase “Chick ’N’ Mix” and a name for a type of skylight – not just the words “Dulwich Hamlet” but also “DHFC” and “The Hamlet”, claimed for exclusive use on printed matter, posters, hats, caps, bibs, baby boots, pads of paper, gym bags, umbrellas, dog leads, flags, football shirts, football shorts, football socks, scarves. There’s been a hamlet at the site of Dulwich for millennia, Catherine Rose said to herself. A team since 1893. What right did anybody outside the club have to claim this history?

A football club like Dulwich is its history, always accumulating. It is the players who come and go and the fans who linger longer-term. It is a thicker and thicker book of uneraseable results, averaging disappointment, scattered through with trophy wins or the piquant memory of near misses. And a football club like Dulwich is also those things that do not change, or should not: a colour palette, a badge, a motto in Latin or English. It is a formal name on a fixture list and the quicker, casual name dropped by fans who think of their team and talk about it too many times a day for wordy ceremony. Dulwich Hamlet. The Hamlet. Only from a distance (and there are 3,569 miles between Champion Hill and the Delaware office through which these trademarks were sought) could such things be mistaken for bargaining tools. “It was so absolute in its audacity,” Catherine Rose said.

The debacle made the national sports pages, and Gary Lineker – the pied piper of football Twitter – posted his influential dismay (“Jeez.”). “Anyone that’s handy with trademark law”, Cullen tweeted, “please DM”. Intellectual property lawyers got in touch, offering to waive their fees. In the end, Meadow transferred the three trademarks to the club’s supporters’ trust, and later acknowledged to me that the wording of the legal letter to Hickey was clumsy. However, it contends that it only secured the three available trademarks to help the club – to close off an obvious vulnerability. (According to the Intellectual Property Office, the applications had been filed on 17 October 2017, one day after the unsatisfying court appeal over the council astroturf.)

At Westminster, Catherine Rose found that news of the trademark writ gave her advocacy mission a boost. The councillor was sitting in the polite surrounds of the House of Lords’ tearoom when Hickey’s message came through. “Kick up a fucking shitstorm,” was the prompt advice of one peer. Roy Kennedy, a Labour-made lord from Southwark who’d attended many games at Champion Hill, took a team scarf and in the coming days ambushed politicians in corridors, wrapping pink-and-blue about any throat he could find for a photo opp. Meanwhile, Catherine Rose consulted with a former colleague from Southwark council, Helen Hayes, now the local MP and empowered to propose government debates. “The situation at Dulwich is not individual,” Hayes told parliament 10 days later. “It is representative of a much wider problem, in which short-term financial gain seeks to assert itself over an institution valued not just in pounds and pence but in people, friendship, aspiration and history.”

Catherine Rose listened to these words from the public gallery. It was becoming clear to her that to hold any sort of political rank was to have more and better ways to protect what you cared about. A councillor for only two years (she’d soon need to fight an election to regain her seat) Catherine Rose decided there-and-then to try for a position that was about to come open, as Southwark’s next mayor. Wait longer, she reasoned, and it could be too late.

On 5 March, a Monday, Meadow made good on the threat to evict. It seemed the club had played their last game at Champion Hill. Turnstiles closed. Hoardings went up. The just-so grass, always cut short to suit Dulwich’s quick football, was left to grow as it would. After considering and dismissing various temporary homes (an athletics stadium, a velodrome), the club accepted an offer to ground-share with their seventh-tier rivals Tooting & Mitcham United at the KNK Stadium in Morden. On 18 March, Catherine Rose was among the 800 who made the trip to Morden for this first not-home game. It was a freezing afternoon, the pitch churned and hard-set. The dynamic Allassani was still out hurt, but even his less-silky teammates found the playing surface stifling. Dulwich’s next game at the KNK had to be abandoned because of rain, when the pitch flooded. They fell to third in the league. And, meanwhile, Billericay won and won and won.

At a council meeting in March, it was agreed that funds would be made available to try to buy Champion Hill from the developers. Meadow said no, and seemed incredulous that public funds would ever be used in such a way. Councillors considered their options, including the use of a compulsory purchase order (CPO) that could force the surrender of the land. At the end of March, Meadow changed tack and submitted a revised, outsized bid to alter Champion Hill, one that would put not 155 but 224 dwellings on the old pitch. This application would have to be considered by Southwark’s planning department, however improbable its consent, and there could be no CPO in the meantime. Dulwich Hamlet would play out the remainder of the season on borrowed ground. “Ballsy move Andy Mac,” Cullen said on Twitter.

Billericay, in the end, were champions. Dulwich’s rivals secured the league title with a week of fixtures still to play. Gutted and glad to be distracted, Catherine Rose was out early on the last Saturday of the season, knocking on doors, shaking hands, canvassing support ahead of the elections. Mid-afternoon she called it a day and went to watch her team play – a meaningless draw, but there were positives. Allassani had returned from his injury, and other less starry players had risen up in his absence, for instance the midfielder Ash Carew, whose needle-threading freekicks were helping the team fashion goals through the air rather than down on the unreliable grass.

Although Dulwich had failed to win the league, there remained a back-door route to promotion, as long as they could battle through two rounds of playoff games. Catherine Rose didn’t know what to be more frightened of – the elections, which were now a week away, or the first playoff game, scheduled that same night.

You weren’t supposed to use your mobile at the count, so the councillor kept ducking outside to follow Cullen’s online updates. Around 9pm there was good news. “Goal … What. A. Noise … Ash Carew steps up for a free kick just outside the area, and the Hamlet are ahead.” Twenty minutes later, Dulwich were through, and five hours after that Rose was reconfirmed in her council seat. Days later, she was confirmed as Southwark’s new mayor, and went ahead and ordered the custom robes she’d been thinking about. Sleeves in Dulwich blue. Collar and facings in Dulwich pink. They had one more game to win.

6. The directors

Liam Hickey’s fear, all along, was that he’d end up as the answer to a trivia question. Who was the last guy in charge of Dulwich Hamlet? That twat? The announcer? Though they were shattered, fraying, still homeless, Hickey’s Dulwich had got through to the season finale.

It was a sunny May Bank Holiday Monday, already tropical by early afternoon. When Cullen arrived at the ground in Tooting, two hours before the playoff final kicked off, the two fans walked around the pitch, talking over the season gone and reminding each other, today, to be fans. They composed a good-luck message for Gav Rose using the WhatsApp group the three of them now used to discuss club business. They called this group “DHFC Exec”.

There had been major changes in the governance of Dulwich Hamlet. The owner, McCormack, had named Hickey and Cullen as co-directors. (Gav Rose later joined them on a new four-man board.) McCormack also agreed to hand over to each new director a quarter of his shares in Dulwich, empowering the trio to outvote him and, in general, steer the club around his worst instincts. As McCormack told it, he did this to “recognise the amount of effort those guys had put in to help the club survive ... I didn’t feel I deserved to have that shareholding any longer.” Acknowledging relief at becoming a fourth wheel at Dulwich, he concluded: “I’ve made enough mistakes.”

Meadow retained hold of Champion Hill, where the grass grew knee-high and the earth began to open in jagged craters. Hickey, Cullen and Gav Rose continued to believe they could get Dulwich back there eventually. For now, they consoled themselves that by surviving till May they’d at least secured a last-gasp shot at promotion. More than 3,000 fans had journeyed to Tooting to see if Dulwich could finally do it. With the kick-off nearing, Hickey took up his traditional position at the back of the main stand, radio mic in pocket. Cullen found a spot in a banked terrace behind the home team goal.

Below, in the changing room, Gav Rose boosted his players. “Many other groups would have crumbled, and that would have been understandable. No matter what happens today,” he told them, “I’ll always remember this group for its character.” Back in at half-time, Dulwich 0-1 down, the coach repeated his message – “No matter what happens” – and sent the players out.

In the stands, thoroughly petrified, Cullen had drunk three beers and almost missed Dulwich’s biggest goal of the season for a wee. Allassani pelted clear. Carew took the ball, measured a pass. There was an excruciating bundle in the goalmouth … 1-1! The score stayed the same till full time, when Hickey’s voice rang around the stadium. “There will now be 30 minutes of extra time.” After another fruitless half-hour, it was still level. On his microphone, Hickey confirmed that the match – the whole fight – would now be settled by penalty kicks.

“It’s pens,” Cullen tweeted, not trusting his quivering thumbs with anything more. He clutched the steel barrier in front of him, and watched penalties rifle in or be saved. After eight or nine, Cullen, frantic, had lost count. He shook the stranger next to him: is this it? Dulwich needed one more.

When they scored, his knees gave way. He rested his forehead on the steel. Down beside the dugout, Hickey reached for his microphone while spectators streamed on to the grass around him. Pink flares were lit. Gav Rose let go of his typical reserve, at least for a moment, and sprinted with aeroplane arms. People were crying. Kenny Beaney clutched his head. Hickey still had an announcement to make. He drew breath: “After 111 years … Dulwich Hamlet … are finally … ”

The party carried on for hours. By nighttime, hundreds had made their way back to a pub near Champion Hill – so many that people spilled out on to a roundabout in the road. Players arrived in their cars and drove celebratory laps, hair still wet from the shower. Mayor Rose was there to cheer. For Allassani, about to get his move through the leagues after all, to second-division Coventry City, this evening was a way of saying goodbye. Same for Beaney, the captain and scaffolder, who’d known all along that, however badly he wanted it, promotion to a more demanding league would signal the end of his stint with Dulwich. At more glamorous clubs they put up shields, statues, renamed whole stands inside their stadiums, to memorialise historic achievement. After Dulwich Hamlet won their playoff game, somebody picked it out for history, this moment, this traffic island; a corrugated plastic sign was cable-tied to a lamppost, rechristening the site “Promotion Roundabout”.

As for Hickey, the reality of promotion started to sink in, he said, around the time the pink flares burned out. “If you’d told me, back in October, that we would get as far as the end of the season without trashing everything we ever had or represented as a club, I’d have said you were bonkers.” Now, really for the first time, he had to think about next season. As a sixth-tier side, travelling further afield for games, facing better teams week on week, Dulwich would be under greater pressure. He was worried that fans wouldn’t keep making the longer journey to a borrowed ground for another year (and crowds did fall sharply).

Another six months would go by, Dulwich teetering, almost toppling, before Meadow and Southwark council agreed to sit down with mediators and settle the battle for Champion Hill. On Monday 22 October 2018, a year to the day after Hickey was asked to take the reins of his boyhood club, it was agreed that Dulwich could return to their hamlet.

They had scrapped their way into the sixth tier of English football. They had stayed alive long enough to get back home. It was quite an achievement. But on the night of the playoff final, Hickey skipped the dancing on Promotion Roundabout and drove back home to Kent. His wife was waiting for him. She was not a football fan – she did her own thing while Hickey was out at his matches. He made them dinner when he got in. Pottered about. His wife asked how they got on, and Hickey said: “We won.”

This article was amended on 29 October 2018, to remove a reference to a team of off-duty police (Metropolitan Police FC no longer consists of serving officers); to state that Champion Hill hosted football at the 1948 Olympics, not cycling; and to clarify the location of Tooting & Mitcham United’s ground.