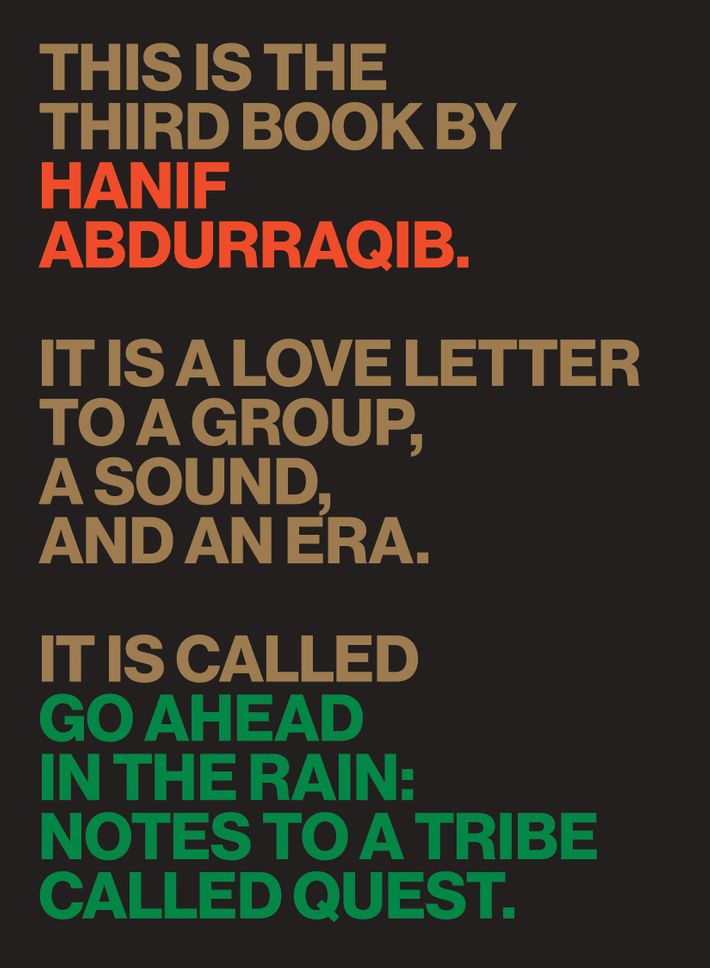

Hanif Abdurraqib is a visiting writer in the MFA program at Butler University, an acclaimed poet, and cultural critic whose work has appeared in the New York Times, MTV News, Vulture, and other outlets. A nominee for the Pushcart Prize, he is the author of the highly praised poetry collection The Crown Ain’t Worth Much and the essay collection They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us. He is currently at work on They Don’t Dance No Mo’, a history of black performance in the United States. The excerpt below is from Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest, a book about the legendary rap group, and his relationship to their music.

If you were a resident of a home that cared about hip-hop in the 1980s and 1990s, your home probably got a monthly delivery of The Source magazine. And if your home didn’t get it, you maybe knew the home of some other hip-hop fan who got it, and you maybe knew you could sneak off with it after they were done with their initial read. My brother kept his issues stacked in a corner, next to the large chest that held all his cassette tapes. Even in the nineties, when the CD player was becoming more and more prominent as the cost of one declined from the early to mid-1980s, allowing more CDs to be produced, my brother stuck with his loyalty to the cassette tape, influencing me to also develop a loyalty to the cassette tape. In all the ways people have listened to music over the past forty or fifty years, it can be argued that the cassette tape is the most tedious and least practical. It offers some of the same satisfaction as listening on vinyl: due to how difficult it is to skip songs, it makes the whole album listening experience vital—something worth celebrating. But the cassette is more fragile and less beloved when viewed through a lens of nostalgia. In the battered Walkman I owned, the tape inside the cassette would often get wound around one of the spokes inside the player, forcing the tape to unravel from the shell of the cassette. Countless tapes were ruined this way, by having to hand-wind the tape back into the cassette’s plastic body, warping the insides and leaving a listener with a cacophony of only barely decipherable warbling.

But despite the fragility of the cassette, when I was young, I appreciated what it demanded from a listener. A cassette locked a listener into a commitment, particularly in the mid- to late 1990s, when rap albums were sprawling, overrun with skits and Easter eggs. To skip a song could also mean you’d miss something. On Wu-Tang’s 1993 Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), for example, one would be wrong to pass over the skit before the song “Method Man,” where Meth and Raekwon playfully spar over excruciating acts of torture; or in 1999, before MF Doom’s “Hands of Doom,” where two graffiti artists discuss Doom as a character, building out the ethos of both artist and persona in a few lines; or any of the children’s storybook skits that littered the 1991 De La Soul album De La Soul Is Dead, creating a narrative around a young kid finding a De La Soul album in the garbage, only to have it stolen from him by bullies who listen to and critique the tape as the album unfolds, ending with them putting the album back in the same trash can where it was first found. The nuances of the album were part of the journey, so one had to endure whatever one must to take it all in.

The value of the tape was also the crafting of a mixtape. I am from an era when we learned not to waste songs. If you are creating a cassette that you must listen to all the way through, and you are crafting it with your own hands and your own ideas, then it is on you not to waste sounds and to structure a tape with feeling. No skippable songs meant that I wouldn’t have to take my thick gloves off during the chill of a Midwest winter to hit fast-forward on a Walkman, hoping that I would stop a song just in time. No skippable songs meant that when the older, cooler kids on my bus ride to school asked what I was listening to in my headphones, armed with an onslaught of jokes if my shit wasn’t on point, I could hand my headphones over, give them a brief listen of something that would pass quality control, and keep myself safe from humiliation for another day.

The trick was recording from CD to cassette. Recording from cassette to cassette was an option, but only for the desperate, because the sound quality in that transfer would drop significantly. But if you had a good CD recorder—as we did in my house—you could set your tape to record songs straight from a compact disc, which not only improved sound quality but made for fewer abrupt stops in the process of recording. I would get CDs from the library near my house, which allowed you to take out five at a time in seven-day bursts. If you were particularly strapped for time or feeling especially confident about an artist or a group, you might just set the CD to record for the entire length of it, copying a whole album’s worth of songs and then sorting them out later. When Beats, Rhymes and Life came out, for example, I remember recording it all the way through. By that time, Tribe had earned a type of currency that engendered that kind of trust. It was assumed that any album with their name on it would surely be worth its weight in gold, with no outright skippable songs. On each of their previous albums, even the less-than-great songs managed to be tolerable.

That trust fell apart on Beats, Rhymes and Life—which doesn’t mean the album was bad so much as it means the album couldn’t live up to the impossible standards of my own imagination. It sat in my Walkman during the winter of 1996, and I would pull my fingers out of gloves and rush to fast-forward what I could before the wind forced my hands back to the warmth they craved, and then I just stopped listening to it altogether.

While undergoing the task of making cassettes, I would often sit on the floor next to the stereo and read through the old issues of The Source that had accumulated over the years. The thing about The Source, in those days, was that it acted as a multilayered beacon for hip-hop culture. There was the unsigned hype column, which turned an eye toward acts that were underground but on the verge of breaking out. There were long, sprawling profiles of rappers that ranged from the delightfully absurd to the emotionally engaging and enlightening. Every issue opened with the hip-hop quotable, highlighting the best rap verse from the past month. Before social media provided a platform for discourse, these would be debated in person, in parks during breaks between basketball games, in barbershops, or in basements. Also, The Source had covers that now seem comical but seemed brilliant at the time—covers that painted black rap stars as larger-than-life and sometimes heroic. Timbaland and Missy acting out a scene from The Matrix, or Puff Daddy hooked to a giant glowing machine, or Dr. Dre putting a revolver to his own head.

But what was more vital than all of this was The Source’s album review system. It was the first album review metric I ever knew, and one I came to rely on. It was simple: albums were rated on a scale of one to five mics. The one mic was as bad as it could get, and a five-mic album was a classic. The Source was known for its hardline, detailed reviews. They were unafraid to take a legend to task if that legend didn’t live up to what they were capable of on an outing, like giving Slick Rick three mics on Behind Bars in 1995—an album he released while incarcerated, no less. The Source didn’t deal in sympathy for circumstances. If an album was to climb the mountain and achieve the heralded five-mic status, it had to be a classic, not just on its first listen but also on its fifth. It had to be the kind of tape you could put in a Walkman and know that you would not need to skip a single song. The Source reviews were a way of life, with the “five mic” vernacular working its way into language used elsewhere, to describe anything that was fresh. It helped that The Source was stingy with its five-mic reviews in its early days. They would get close with many albums, giving out the 4.5-mic review almost as a tease and debate starter. But over the magazine’s first ten years, from 1988 to 1998, it only gave out five-mic reviews to nine albums total, with four of them coming in 1990 alone. The albums bestowed the honor of the five-mic review within that first ten-year window were as follows:

Let the Rhythm Hit ’Em—Eric B. and Rakim

AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted—Ice Cube

One for All—Brand Nubian

De La Soul Is Dead—De La Soul

Illmatic—Nas

Life After Death—The Notorious B.I.G.

Aquemini—Outkast

The other two were two albums by A Tribe Called Quest: People’s Instinctive Travels and The Low End Theory both secured the honor, making A Tribe Called Quest the first act ever to have two five-mic albums awarded by the magazine. Later, when the magazine went back to rerate albums that they either didn’t get to upon their release or that they felt deserved a rating adjustment, others like Ice Cube and Run-DMC were rightly added to that group. But early on, it was just A Tribe Called Quest, alone at the top of the mountain with a hand on each masterpiece.

In October of 1998, the cover of The Source sent especially jarring shockwaves through the communities it landed in. Against a soft blue background, all three members of A Tribe Called Quest are cloaked in black. To the right is Phife Dawg, round sunglasses atop a head full of waves, looking at the ground. On the left, also looking at the ground is Ali Shaheed Muhammad, somehow looking even more morose than Phife, his lip protruding slightly. In the center is Q-Tip, the only one looking straight at the camera, but through a low hat, his head bowed slightly, his eyes fixated on the cameras lens—one of the few white things in the shot. It is a piercing photo. Even if one didn’t read the words below the picture, it would be obvious to anyone holding the cover that something had gone or was going awry. The words below the picture confirmed every worst fear: “Exclusive Interview: BREAK UP! A Tribe Called Quest Disbands.”

Excerpted from Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest by Hanif Abdurraqib, © 2019, published with permission from the University of Texas Press