MUMBAI — I must have been 13, and it must have been 2 or 3 in the morning when I took off my purple digital watch and started pulling hairs from the pale strip on my wrist where the watch had been. I needed to know what my skin looked like with no hair on it. I needed it to be where nobody else would see.

I pincered each hair between index finger and thumb, sometimes pinching skin instead. I left scratches and drew blood but kept going. I already knew to bear brutality for beauty. I was left, finally, examining a hairless wrist under the brightest bathroom light. It was tender and angry and I loved it: my secret stripe of real woman skin.

For the next week, I found private confidence in sliding a finger under my watch during classes, on the school bus. Still, I couldn’t show a soul. The shame wasn’t about removing hair. The shame was in the yearning. To tell anybody what I’d done would be to admit a truth I wasn’t ready to hold: I am growing repulsed by the body I see when I look down at myself. I want, with mad desperation, to fix it.

I don’t remember the first time I saw a woman’s hairless skin and felt the need to look that way. Beauty was a continual education, going back earlier than memories. It was a lesson taught by every piece of visual culture — on TV, in movies, on billboards at every stoplight — and every morning, my mirror delivered a failing grade. No syllabus was ever taught so well.

Thirteen years later, oxblood nail polish covers my nails, and Mac’s NC42 compact evens craters left behind by acne and epilation mishaps. Dark lipstick fills chewed-through lips. Hair is tortured out of my body with lasers, hot wax, and thread. The hair on my head is left to live but isn’t spared. It’s tamed by an anti-frizz and curl-control regimen, seared daily in the clamps of a hot iron. I am a dream consumer of beauty, and I am far from alone.

For more on this story, watch Follow This on Netflix.

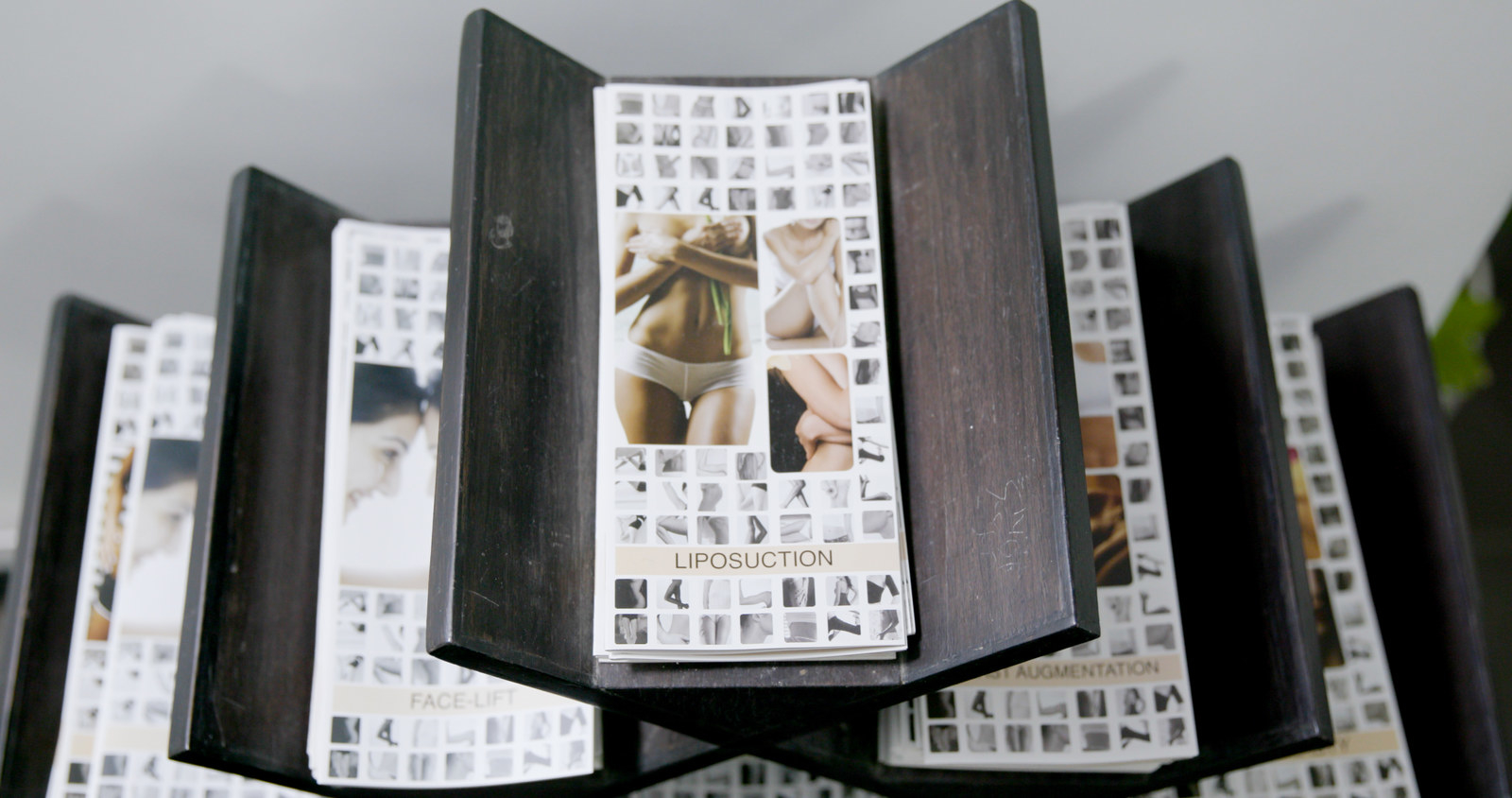

India’s beauty and wellness markets are growing 18% year over year, around twice as fast as those in the United States and Europe. Indians are estimated to spend something like 80,000 crore rupees ($10 billion USD) on beauty each year, and that number is expected to triple in the next five years alone. India’s weight-loss and skin-lightening industries are in full boom, while eating disorders and body image issues rise with them. We are home to the fifth-highest number of plastic surgeries annually in the world.

This explosion began in earnest in the ’90s. In 1991, the year I was born, the Indian government began to reform the economy to avert an economic crisis and make it much easier for foreign companies to set up shop here. As I grew up, MTV and Nickelodeon beamed white faces and shiny brown hair into my home. Elle and Cosmo landed on coffee tables, introducing us to new neuroses like cellulite and age. L’Oreal and Revlon found half a billion new potential customers and launched a never-ending campaign to convert us.

In 1994, the models Sushmita Sen and Aishwarya Rai brought home the corporate crowns of Miss Universe and Miss World, respectively, cementing a national aspiration to be considered beautiful by global standards. Both women went on to have long careers in Bollywood and up on billboards, forever tempting us with the mystery of whether they were born with it or whether it was Maybelline.

So in looking for someone to blame, my eyes fall easily on Bollywood stars, the most visible women in India. Images of them can feel like a hallucinogen sprayed over us, transporting girls into a fantasy where we will only succeed if we subscribe to the rules they set.

Fortunately for me, my career grants me glimpses into Tinseltown greenrooms and through the façade. I once sat with superstar Sonam Kapoor in her home, hearing about extreme diets she’s felt pressured to try before a shoot, the times she pushed herself beyond healthy limits of exercise because of a snarky comment in a gossip rag.

Kapoor was once a teenager who hated her body for not looking like she wanted it to. Now, on the other side, she knows why it didn’t. “It takes an army, a lot of money, and an incredible amount of time to make a female celebrity look the way she does,” she said. “It isn’t realistic, and it isn’t anything to aspire to.”

On another day, I’m with Swara Bhaskar on her living room couch, with her cat, Item, dozing between us. As a Bollywood star, Bhaskar isn’t even known for glamour as much as she is for her skills as an actor and her progressive viewpoints. Still, she is beautiful in the inaccessible way that stars are: impossibly shiny wherever one should shine, perfectly matte wherever one shouldn’t. Much thinner in person than you expected. Somehow sweating less than I am.

The 13-year-old inside me sits up, itches to pull hairs out, maybe skip dinner. Then I ask her what’s “unreal” about her appearance right now.

“Braces…” she says, trailing off because she has her mouth open wide, and her face tilted to the ceiling to show me the metal behind her upper teeth. “There’s makeup. There’s hair extensions.”

She pauses to think. “Oh, Spanx!”

She lifts the hem of her dress a few inches to show me the beige second skin under it.

I feel the veil lift. An exhale.

The last time I saw Bhaskar was on a very large movie screen in Veere Di Wedding, in which she played a brat party girl, glamour turned up to 11. She tells me about the diets and fat-freezing she attempted to look the part. She knows that confessing to those interventions is risky, but, thank god, she doesn’t care.

“It’s almost like admitting that you weren’t perfect enough,” she says about where the self-hate comes from. “So you had to do something to seem more perfect.”

That’s the bind we’re in, famous and unknown alike. The pressure to appear perfect seesawing with the shame of admitting you weren’t already, all held up by booming industries that urge us to make the transition.

I thank Bhaskar, hug her goodbye, and catch a rickshaw home. Flying through drizzle and sea breeze, I see the women beaming down from billboards with a new softness. They are my jailers, yes, but they are also fellow inmates, maybe even in some tighter binds. Specifically, a bind of silence.

To understand the hush, you just follow the money. Celebrity flawlessness is a foundation on which our $10-billion-and-growing beauty market stands. The language of cosmetic advertising has insisted that the highest tiers of beauty are accessible to everyday consumers. “Marks se Nomarks, ab sach mein possible” and “Real results in just three uses.” Meanwhile, the images alongside these slogans are of celebrities who look the way they do thanks to a host of much less accessible interventions. If we knew how many painful, exorbitant procedures create those faces, we wouldn’t buy the myth that we could look like them by buying the products they’re selling us.

The least famous of us do our grooming in 15-square-foot rooms with glass fronts, where very grouchy aunties toss floral nylon robes at you and wax your thighs right there, standing up, wedged between a college kid tearing up through her upper-lip threading and a housewife trying to sustain a phone call through a blow-dry. Stars groom much more privately, with consultants and surgeons used to nondisclosure agreements.

One such keeper of secrets is Dr. Varun Dixit, a surgeon to the stars.

He looks like a very sweet man, and I’m a little let down by it, to be honest. I had dreams of writing about a diabolical, stone-cold love child of Anna Wintour and the Joker, scalpel in hand. Instead, Dr. Dixit is kind-faced and bespectacled, out of breath, saying sorry a lot for being a little late.

A full third of his patients, he says, are “known faces.” They prefer to visit discreetly. For them, there’s a side door leading directly into his clinic from the parking lot, bypassing the lobby and waiting room. If celebrities are seen visiting a plastic surgeon, “they’re worried that the media would uchhalo it” — make a bigger deal of it than it is.

“In India, we have so many gods who are picturized or idolized as a perfect being,” Dr. Dixit tells me. “That’s what happens with these celebrities.” Audiences revere these stars so devoutly that we all need to believe “their looks are God-given.”

It’s not an unfounded concern. After debuting an enhanced lip pout in 2014, A-lister Anushka Sharma found herself in an extended din of trolling and criticism that she’s had to address in interviews for years afterward. “I just wanted to end the noise,” she said once. “I felt bullied. I didn’t know that people could be so mean. Some of the stuff was quite funny, but some of it was pure vitriol, and I cried.” Who wouldn’t?

The stigma showed itself again last year when one fan named Piyali Ganguly suggested on Facebook that perhaps veteran actor Sridevi, who died under mysterious circumstances, had suffered compromised health because of a lifetime of cosmetic interventions. Outrage erupted online, and Ganguly received widespread bashing, even death threats, for the mere suggestion that Sridevi might have undergone surgery. It was a critique of beauty standards, but it read to fans like a criticism of Sridevi herself.

In a stupider-than-fiction twist, the shroud of shame is now upheld by the same people it exists to dupe — the audience. The consumer. Us, ourselves.

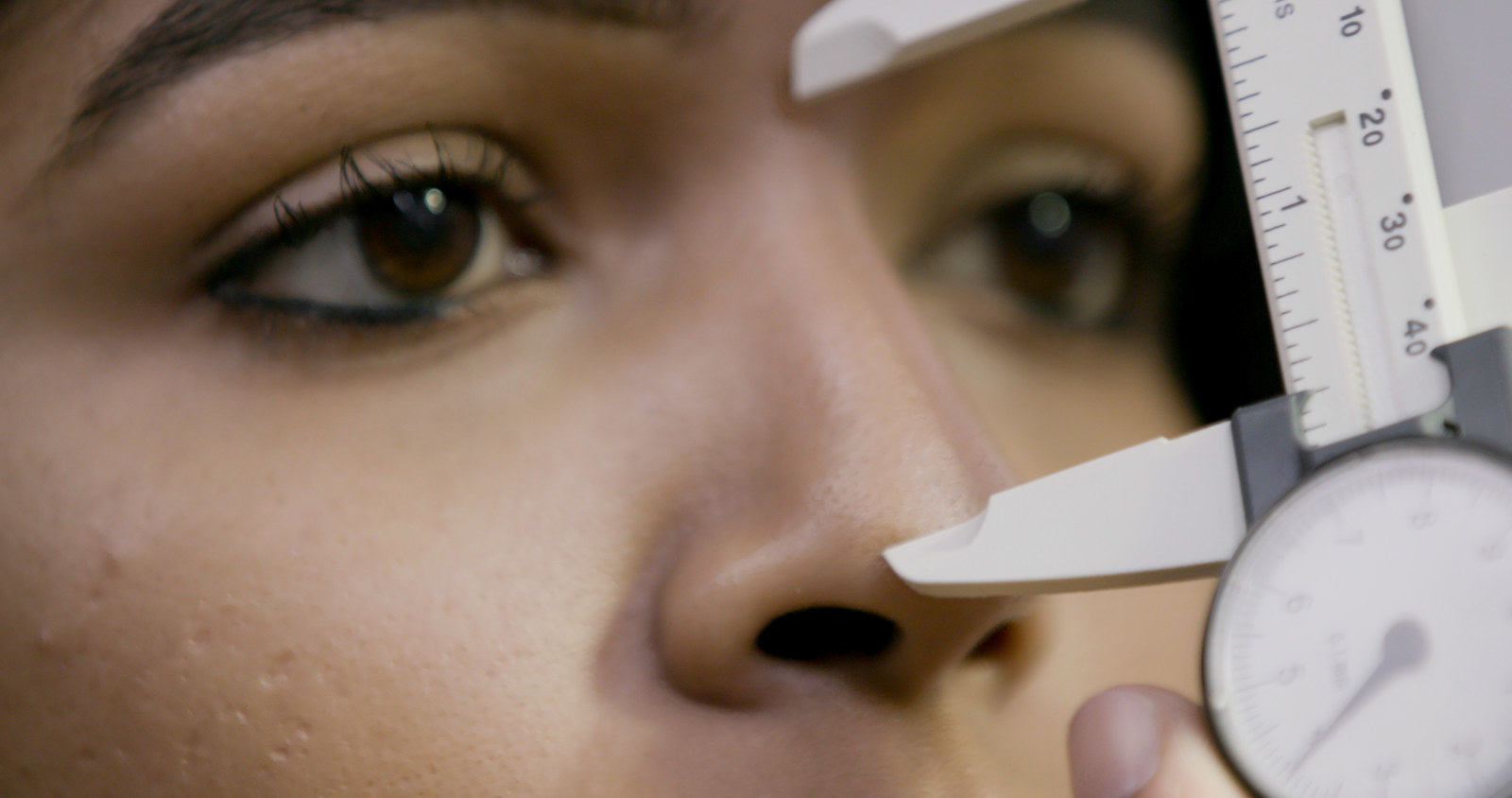

I finally ask Dr. Dixit the question I’ve been dreading all day: Pretend I’m here ready to go under the knife and come out God-given gorgeous. What would we do?

“I don’t think there’s anything really, majorly wrong with you,” he starts off. The “really” and “majorly” sting for no real, major reason.

He turns the question around: What are my facial features I don’t like? It’s too easy: I’ve been compiling this answer for years. My nostrils are different sizes. My chin doesn’t go out far enough. My lips could honestly use clearer definition on the lower right side, and my eyebrows, oh god, what even is symmetry? Also, my eyes are entirely different shapes. There’s more, too. But I give him the easy version: My chin sucks, and the left side of my face is hotter than the right. I wonder how many therapy sessions I’m undoing in this moment.

Dr. Dixit lets me know right away that my chin isn’t the problem. “Just reduce the prominence of your teeth,” he says. “But if you’re happier with your lips pouting that much, don’t touch your teeth.” My lips pout. Who knew?

We do mugshots against a white wall. Front facing, left profile, right profile, close-up. Something about it does feel criminal, but I try not to think about it. “We can fix it all up,” he says and gets to work.

The face he shows me 10 minutes later, in the edited photo, still doesn’t look beautiful to me — she’s a smoothed-out twin, too uncanny to find anything but weird. I know that she is beautiful. More so than me, even. Looking like that might be easier to enjoy. But I also know with dawning clarity that, even with that sharper nose and symmetrical jawline, she’d have her own novel inventory of wants; she’d find something else to wish were different.

I thank Dr. Dixit and leave, hoping that I’ll manage to shake off the mental print of that other me. Her allure is real, but so is the shame of even thinking about her.

It must have been 2 or 3 in the morning some night since when, alone in my bedroom, I swiped open my phone camera and pointed it at my very hairy legs. I had to turn on more lights so the camera would catch the hairs, and use portrait mode so they’d really stand out. Eventually I had the photo I wanted for my Instagram.

For an hour, I refreshed every minute or two to see how many views it had. A hundred, then a thousand, then 10,000. I paced the room, my thumb hovering over the trash can icon that promised to erase this hideous admission from the internet. I didn’t do it. It was ugly and frightening, yes. But I loved it. My public proclamation of real woman skin.

The next morning, my inbox was overflowing. Women around the country had sent me their photos: a mirror selfie in a sundress, hairy legs all the way down to white sandals, text overlaid that said only “thank you.” Another pair of legs, feet up on a sofa, stubbly thighs blooming out of denim shorts: “I had a waxing appointment but I saw your post and didn’t go.” A message from a girl whose birthday it was, who bought a cute dress but was shy and considering jeans because of her stubbly legs: “I wore it.” Hairy legs at a café. Hairy legs in school uniform culottes. “After seeing your post I stepped out of my house in a dress and legs unshaved for the first time in my life. It was liberating.”

The messages didn’t stop, and still they haven’t. Every other one revolves around that word: liberation.

I put my phone away and feel the hairs on my left wrist where that purple watch used to be. I remember the stings and scratches, then all the razor bumps and wax burns, all the thread cuts and laser scars. All the hours spent waiting for nail polish to dry, all the chemicals I’ve allowed so close to my eyes that see and my mouth that eats and kisses people. I remember all the times beauty has drawn tears of physical and soul-rattling pain.

I sit with that girl with the shiny wrist, seeing her arms and legs coated in baby fuzz, her eyebrows a bush, hair left to frizz. I wonder what she might be like today if all the forces in the world hadn’t taught her self-loathing. There is no shame anymore in having yearned for what the world promised to accept. But a new yearning is here now too — to look down and see a body that’s free. ●

Rega Jha is a writer interested in the overlaps of popular culture, digital behavior, gender politics, and youth wellbeing. She studied writing at Columbia University, founded BuzzFeed in India in 2014 and served as its editor-in-chief for four years.