Published on

October 18, 2018

Category

Features

Who were Skull Snaps and why did it take forty-five years to find out?

In early 1973, a trio of musicians yet to be called Skull Snaps went into New Jersey’s Venture Sound Studios to record an album. It didn’t take long. Laying down each track in a single take, the record that became Skull Snaps would go down in hip-hop folkore, featuring one of the most sampled break beats in history.

But while the drum intro for ‘It’s A New Day’ would lay the foundations for tracks by everyone from The Pharcyde, Eric B. & Rakim, Digable Planets, Common, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, to massive chart outfits like The Prodigy, Linkin Park, and even Alanis Morissette, the band behind Skull Snaps – Samm Culley, Ervan Waters and George ‘Buzzy’ Bragg – were written out of history, lost behind that sample and that iconic, unusual, macabre album cover.

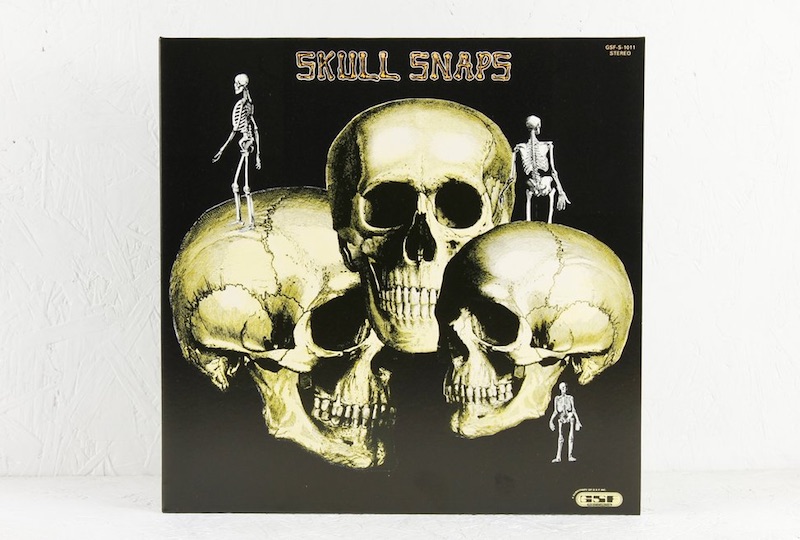

Record collectors, producers and crate diggers like a good creation myth, and Skull Snaps’ self-titled ‘debut’ had it all. A mysterious funk trio, who recorded one album under a curious name, housed it in a sleeve that looked more like a proto-metal album, and released it through a label (GSF Records) that folded shortly afterwards? Everything pointed towards the Skull Snaps album as a single totemic object, packaged in a way that predicted its own disinterment twenty-five years later.

For those who sampled it, myth maintenance was advantageous, both for their reputations and for their consciences. Likewise, an unsanctioned 1995 reissue on Charley Records removed the credits from the inner sleeve to further sever the record from its context – or perhaps because the label couldn’t quite face using the names of artists they had no intention of paying. Either way, owning the record was a right of passage, as Amir Abdullah once wrote: “If you don’t have Skull Snaps in your collection, your collection is weak.”

But the band itself was real enough, and by the early ‘70s, Skull Snaps’ Samm Culley and Ervan Waters had built reputations as seasoned vocalists. As members of RnB close harmony group The Diplomats, they released eleven 7”s on various labels between 1963 and 1970, performed regularly at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem and were among the first RnB groups to play Carnegie Hall.

Later in 1973, Skull Snaps would appear again under a different name, cutting a cover of Manu Dibango’s ‘Soul Makossa’ for Buddha Records. “They basically asked us to do it overnight, but we couldn’t put our name on it because we were under contract to do something else, so we used the name All Dyrections,” tells Culley, employing the poetic license afforded to someone who has been mythologised out of history for too long. “We went in that night, recorded it, they released it the following day, and by the following night it had sold 35,000 copies.”

That same year, the trio played on Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ ‘Africa Gone Funky’ – a heavy grooving 7” for London Records that would end up on Hawkins’ 1977 album I Put A Spell On You. Skull Snaps were not part-timers, and the record was far from a flash in the pan.

Instead, Skull Snaps captured a band at the height of their powers; a tour de force trio that would tear through covers and original material all night long, flabbergasting audiences and contemporaries alike with their energy and stage presence. “Maybe twice we ever rehearsed in our whole careers”, tells Culley proudly. Ray Charles, Ella Fitzgerald, Barry White – the band could do the lot, playing clubs for weeks on end where they would make three sound like ten; either mimicking an Echoplex by looping Bragg’s drums through the PA system, or performing horn arrangements with their mouths.

“I remember we did a gig together with Kool & The Gang in New York, and when they saw us set up these little three pieces, I heard them say, ‘What the hell are they going to do with three pieces?’ But when that drum beat started, they flipped around in those seats and said, ‘What the hell is this?’ It blew their minds.”

Or in the words of Lloyd Price, it snapped their skulls. Although specialising in close harmonies as The Diplomats (so close “there was no way to fit another damn voice in the harmony set-up”), Culley (bass) and Waters (guitar) were no slouches on their instruments either. In hooking up with drummer George Bragg, the band felt it had the best of both worlds: a tight rhythm section that pointed to the heavier, funkier sound of the ‘70s, and the vocal sophistication of doo-wop groups and modern soul stars like Otis Redding. When Price saw them perform one night, in Culley’s words, “he just sat there with his mouth open.” The story goes that Price spoke to the band after the gig and asked: “If you’re not going to use The Diplomats name, what can your name be, sounding like that? Because when I listen to you, it’s like to snap my fuckin’ skull.”

In that moment, Skull Snaps were born. Inspired by American rock outfit Three Dog Night, the concept for the album cover swiftly followed. “At that particularly time, black music wasn’t doing that great, and you had the problem of being able to get the plays that you wanted, especially in the pop areas,” remembers Culley. “So, we decided not to have our pictures on there, so people really couldn’t know who we were. If you went into a record shop and saw that album sitting there and you’re a rock fan, you’d say, ‘Damn, let me take that home and see what it is.’ But when you get it home, you find out it’s not a rock album, but you like the album anyway.” It was a piece of covert marketing, and an indictment of an industry that obstructed black artists in getting their music heard. As a result, Skull Snaps had inadvertently written themselves out of one of the biggest stories in hip-hop history.

Not that they knew it at the time. When Skull Snaps went into the studio in 1973, they had two main aims: to show off the versatility of their compositions and the energy of their live sets. Between trainee studio engineer Ed Stasium (who would go on to work with Ramones, Talking Heads and countless others), producer George Kerr, and the arrangements of Bert Keys, Skull Snaps pieced together an album that moved effortlessly between conscious, orchestral soul (‘My Hang Up Is You’), the Blaxploitation-era ‘I’m Your Pimp’, slow-burning ballads like ‘Having You Around’ and the classic funk sound of ‘Trespassing’. The arrangements were punchy, and ambitious – Keys drafted in a bemused member of the New York Philharmonic to play the harp on the session – and Culley was over the moon with the end result. “Bang, bang, bang, bang, bang. All of those songs are one-take tracks. It was surprising to us, but we were just really ready for it.” And yet for decades, this extraordinary achievement resonated for little more than a highly compressed two-bar drum loop.