“PREPARE FOR DEATH”

A man who once stared down Afghan warlords is now transforming NFL stars. This is the inside story of Tareq Azim, pro football's most revolutionary trainer.

The people who loved Dion Jordan tried everything to help him, and when everything failed, they deceived him. They said they'd booked him a belated birthday getaway; he'd go home to San Francisco. They'd even bought him tickets to see the Giants, his favorite team. Jordan had passed that summer of 2015 in the dark stale quarters of his house in Chandler, Arizona, grabbing bottles from his liquor cabinet, occasionally chasing the drinks with Ecstasy. He had refused to answer texts or phone calls about how he was doing during his one-year suspension from the NFL for the drug tests he'd failed. But the allure of the Bay Area trip and the seats along the third-base line briefly lifted his fog of despondency, and got him to pack an overnight bag and board a flight with his girlfriend, Paige Pettis.

The couple landed and, while they did watch the game, they headed afterward to the office of Doug Hendrickson, Jordan's agent and Pettis' co-conspirator. Hendrickson had braced himself, but to actually see Jordan, his stained coat, old and smelly T-shirt, disheveled hair? The 25-year-old looked homeless -- so far removed from the defensive end Miami had drafted third overall two years earlier that Hendrickson actually feared for Jordan's life.

Come with me, he told Jordan. They walked a couple of blocks and stepped into the gym on Front Street run by the trainer who was more than a trainer, and the real reason for this trip. It was a sparse setup, no weight machines, very little gym equipment. The trainer who was more than a trainer was in his office in the back. Hendrickson knocked on the door. "Dion needs you," he said.

The trainer looked at Jordan, astonished.

He turned to Hendrickson, nodded and set himself to his task.

When Jordan emerged from the office an hour later he knew two things. One: He was moving to San Francisco. And two: He was not leaving the trainer's side.

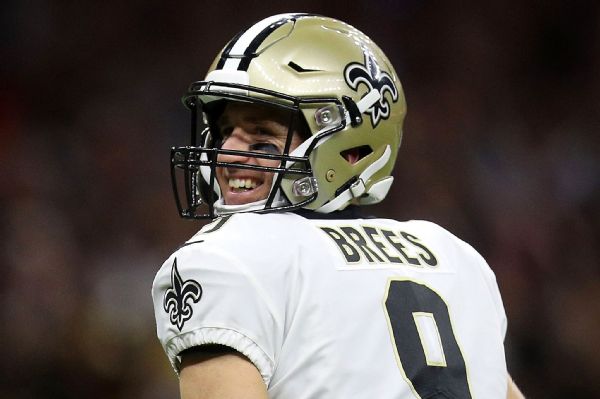

MMA fighter and Ralph Lauren model Luke Rockhold, left, rests during his workout with Tareq Azim. Talia Herman for ESPN

EVERYONE CALLS HIM T. It could stand for trainer or teacher, but really it's a play off his first name, Tareq. Today, one of the final days in July before NFL players head to training camp, T busies himself in the Front Street gym he named Empower. So many people are here. All-Pro Rams corner Marcus Peters sits on an exercise ball in the calisthenics space just off the main hall, nodding his head to the hip-hop blaring from the speakers, thumbing a message on his phone. He came to Tareq Azim in part because Peters' cousin, Marshawn Lynch, trained here; Azim helped Lynch unleash Beast Mode. Lynch still refers to Azim as "family," and Peters calls him "big brother," mostly because of what Azim has helped him realize away from the field. "It ain't about ball," Peters says.

Raiders running back Jalen Richard sits next to Peters on a plyometric jump box, staring at the racks of dumbbells against the far wall, preparing for the hell that will be his workout. Two years ago Richard scored a 75-yard touchdown against the Saints on his first NFL run. What remains as surreal as that afternoon are the conversations he has now with Azim. Take the previous Sunday. He went to a barbecue joint with Tareq and his brother Yossef, a cop who patrols the Tenderloin, San Francisco's toughest neighborhood. Tareq started talking about Afghanistan -- how a decade ago Tareq had stared down Taliban warlords to reclaim his family's ancestral lands -- before shifting to a discussion about the conditions of poverty wherever they are found, the actions they excuse and the lives they constrict. Richard nodded his head. He's from Alexandria, Louisiana, in the central part of the state, and had such a bleak and blinkered childhood that the 75-yard touchdown against the Saints? It was the first time either he or his parents had been to the Superdome. "The conversations we have, that I have with T," Richard says, "I don't really have those conversation with nobody else."

Brushing past Richard now is Azim himself. At 36, he still possesses the compact power he had as a D-I linebacker, and he walks quickly to catch up to Jed York, the owner of the 49ers and a client here. York finished a workout 20 minutes ago and is still in gray shorts and a black T-shirt. Azim leans in close so York can hear him above the blaring music. They are business partners too, York so intrigued by the ethos of Azim's gym that he had a separate Empower built within the Niners facility in Santa Clara, for staff and administration. "The best thing about T, he just cuts through everything," York says. "There's no pretense."

As Azim and York navigate the gym, they do so carefully because of all the Englishmen. The place is teeming with them. Yesterday, the coach of England's Sevens national rugby club stopped by. He'd heard about Empower, the secrets that athletes learn here, and with the 7-on-7 Rugby World Cup at AT&T Park this weekend, his lads were in need of a place to lift. Brawny rugby players with black jerseys and pale skin are everywhere, squatting in the squat rack and prancing around the heavy bags, hard against the boxing ring, or just standing against the wall here in the calisthenics room, sizing up the six NFL and MMA guys who are about to take their orders from Azim.

I catch Tareq's eye as he finishes with York and make a face that says, This is nuts. His smile says, Just another Tuesday. It's true. Luke Rockhold, a former UFC champion and the new face of Ralph Lauren (not joking) is here all week. Gavin Newsom, very likely the next governor of California, will be here Thursday. Dion Jordan, after meetings and workouts with the Seahawks in Seattle, will be back Friday.

The music gets louder and still more aggressive, a cue for the NFL and MMA crew to finish stretching. I join them. Because I wanted to experience what makes this place different, Azim had suggested I work out with the pros. I look around me as I stretch my triceps: The room is 30 paces long and FieldTurfed, with mirrors lining the left wall. What will happen here?

Azim walks before us. He is all broad chest and cauliflower ear and alpha male energy. Hollywood would cast him as a successful D-I wrestling coach. He likes to listen to people and when he at last interjects, his honesty is often bracing. "Take a lap," he says, in the voice of your favorite P.E. teacher. And so we do, out against the cool breeze, past the tech startups and the park where the homeless mingle, then back into the gym and the calisthenics room.

The Empower gym trains athletes across a broad swath of disciplines. Talia Herman for ESPN

We will do a leg workout, high intensity, using only our bodyweight. Azim teaches "humility," he says, and if NFL guys (and ESPN writers) struggle to lift even their own bodies, perhaps they will pick up on the deeper lesson of our temporality, how death is coming regardless and if one "prepares for death," one can seize each day fully, be not just a sack leader but a great husband, father, brother, human. For Azim's faithful -- and they are "not normal people," he says of the iconoclasts and castoffs of the NFL and combat sports -- the workouts aren't only about getting "comfortable with discomfort" but metaphors on the redeeming qualities of the human condition. It is a threatening message, especially for leagues that ask their athletes to play and hit but never question. It is also a message that has allowed Azim to move from an outsider to the insider's insider, the sort of guru who turns away more athletes than he could ever train and declines, routinely but also respectfully, the offers from NFL clubs to come on as a special liaison to players.

We start with a series of squats, then hold the stance when our butts are parallel to the turf. We stay there, frozen, and from that position Azim tells us to lift one leg and stomp it down. Stomp, stomp, stomp. Over and over. The burn is excruciating. "Keep it up!" Azim shouts. We grunt. I let loose a gasp of pain. Still we stomp.

"Time!"

It is over. It is not over. The other leg now.

And this is one set of four.

We do just-as-difficult movements on the floor to strengthen our glutes and hamstrings. Halfway through the workout, I feel lightheaded. Black dots appear on my vision's periphery. I think about how I will not embarrass myself. I will not faint in front of the pros. The dizziness passes.

The hardest exercise is the last. Azim puts medicine balls on the floor. We are to squat down behind the balls and push them across the turf to the far wall. It sounds easy. It is also impossible. My hands ride up the leather casing and the heavy ball loses all momentum and I tumble ahead of it and splay across the turf. I try to get the ball moving again, but it's brutal, my legs quivering from the burn, and when I think I've found the right position on the ball, my hands inch up once more. Now I am embarrassing myself.

We push the medicine ball many times. Some pros struggle too. Before my last round, I tamp down the frustration and humiliation that had powered my previous attempts. I exhale and study the ball. I choose a lower position and tell myself to be in concert, my hands and feet pushing as one. I grunt, and this time the ball glides across the turf. Azim comes over and kicks the side of his foot against the ball to slow my momentum, something he has done with Marcus Peters, who's mastered this drill. Like Peters, I'm able to keep my hands low, my hips back. Azim keeps kicking, but I cannot be stopped.

I reach the far wall. He smiles at me.

"Good!"

Azim, shown here with clients at Empower, has a lifelong affinity for boxing. Talia Herman for ESPN

FOR AZIM, EMOTIONAL resilience and even physical strength are born from the moments that humble us. Azim first learned the lessons of humility as a kid in Concord, in the East Bay. His family ultimately settled there as refugees after they'd fled Afghanistan. They lived in Section 8 housing. Sometimes they didn't have enough food stamps to buy milk. It was quite a contrast to their old lives in Kabul.

Tareq descended from Afghan nobility. His maternal great-grandfather brought fighter jets from Italy and established the Afghan Air Force. His maternal grandfather, Gen. Shaw Wali, commanded Bagram Air Base and was close to the Afghan royal family. There are photos of the general with Queen Elizabeth. Tareq's parents "grew up with golden spoons in their mouths," he says, part of an Afghanistan in the 1950s and '60s that was open to trade and had a robust press, back when Europe influenced the country's fashion and many women chose not to wear hijabs.

The Communist takeover of the late '70s changed everything. Anyone who stood up to Soviet rule after the coup d'etat was imprisoned, tortured and killed. The Communists came for Gen. Wali in 1979. He said to his wife as he was escorted out of his house: "Don't turn your back on Afghanistan."

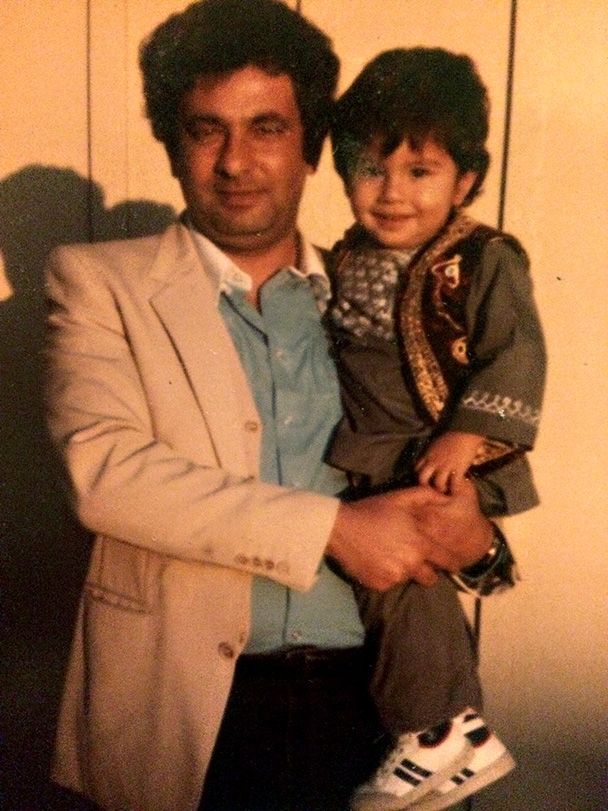

Tareq and his father, Sayed, after the Azim family arrived in America in the early 1980s. Courtesy Tareq Azim

His family had to, though. They would have been killed otherwise. But the general's last message became family lore, and his daughter Mina kept his words with her as she and her husband, Sayed Fazel Azim, raised their three kids in mangy Concord. The couple talked endlessly of going back to Afghanistan, the duty each Azim owed the nation -- lay the bricks for a better life there, Mina often said -- even as their children acclimated to the States. Dina, the oldest, played volleyball. Tareq and Yossef took up taekwondo before Tareq found boxing, then soccer, then track. In the East Bay's immigrant communities, "I used to get bashed all the time," Tareq says. "'Look at him: He's doing all the white-boy s---.'"

Tareq needed the distraction. His father had episodes of manic depression. Tareq remembers one time as a boy when he climbed a fig tree. His dad loved figs, and when Tareq had grabbed enough from the branches, he bundled the gift in his shirt and ran back to the house.

"He was sitting on his bed, just sitting there staring straight ahead," Tareq recalls. The young son yelled, "Dad! Dad!" but Sayed kept staring. He wouldn't look at anything but some point on the wall. Tareq, scared, dropped the figs to the floor. He tried kissing his father to shake him from his trance. When that didn't work, he ran from the room and called 911. The ambulance took Sayed away in a straitjacket.

Sayed's mental illness became something -- like the menial jobs he and Mina worked -- that the Azim family simply dealt with. "We grew up like, 'Hey, give Dad his medicine,'" Tareq says.

Tareq found a release in football. He'd come to the sport late, starting as a kicker on the freshman team -- soccer carried ancillary benefits -- and discovered he liked hitting people more. "I got addicted," he says. With his background in boxing, he had great hand-eye coordination and became a fast, aggressive outside linebacker. He dreamed of being the first Afghan-American to make the NFL. He averaged a sack a game his senior year and led the Ygnacio Valley Warriors to the Northern California sectional championship.

After two years at a juco, Fresno State saw promise in Azim but couldn't settle on where to put him. He moved from linebacker to rushing defensive end to fullback. The Bulldogs' coaching staff said they'd return him to outside 'backer for his senior year. Just before it started, Azim ruptured disks in his spine. The surgery and recovery time consumed almost all of his season. Still, he remained optimistic: With a good pro day, Azim knew he could latch on to an NFL team.

While Azim trained in the early months of 2004, his father had returned to Afghanistan. Large swaths of the family's ancestral acreage in Kabul, and in the Kunar and Nangarhar provinces, where Tareq's family was akin to tribal royalty, were being sold off, often to warlords, and without Sayed's blessing. He had to reclaim it.

Tareq loved his father; Sayed was kind and gentle. Could the aging man really stare down a warlord? Would he in his native land have another flare-up of the illness that had worsened in the States? Sayed never pressed, never even asked Tareq to join him, but the son knew he had a choice: fealty to Afghanistan or to his dreams of the NFL? The question was really the loudest refrain yet of the chorus he'd heard his whole childhood: Will you lay the bricks for others or lay them for yourself?

DAYS AFTER TAREQ graduated from college, Sayed got a call from a number he didn't recognize.

"Hello?"

"Dad. It's Tareq."

What's this, Sayed said? Some Skype number or something?

"No, I'm in Dubai."

Tareq was calling from a phone at the airport. "I arrive in Kabul at 10 a.m. your time."

His younger brother, Yossef, had told Tareq not to go. "It's chaos," he'd said. The American-led invasion in 2001 had snuffed out the members of al-Qaida who'd trained in Afghanistan but now, some two years later, with America fighting a second war in Iraq, Taliban warlords and other tribal sects had re-emerged, battling over old territories. The Afghan government was too weak to stop them. It was so unsafe in Kabul at the time, Pulitzer Prize winner Steve Coll wrote in "Directorate S," a clandestine history of the U.S. war in Afghanistan, that when an SUV in a heavily armed American convoy one day accidentally struck a woman wearing a burqa, no soldier stopped to get out. No vehicle in the convoy even slowed to see if the woman was alive. If American convoys stopped, American convoys risked getting blown up. The vehicles continued to the airport, where they picked up Hillary Clinton, then a U.S. senator and vociferous champion of the rights of Afghan women.

Tareq Azim flew into that same airport about six months later. He had "bad intentions," he says. He'd learned that some of his Afghan relatives had been the ones to secretly sell plots of his father's acreage. To get the land back, especially from the warlords whose attitude was Try to get me off it, "I would react however they acted," Tareq thought. "If they wanted to punch, I would punch. If they wanted to shoot, I would shoot."

After landing on the decrepit runway, deplaning via a rickety ladder, and seeing on the 10-minute drive to his father's Kabul estate the effect of 25 years of war -- the bombed-out detritus of "commercial" districts, a woman who begged and held up a starving and perhaps dead baby by its ankle -- Tareq was "extremely disgusted with myself," he says. How could he add to this carnage? Wasn't this place, this much-mythologized place, which had become the fourth-poorest country in the world after a war with the Communists and a second with itself and now a third featuring the Americans, wasn't this place also in need of something hopeful, something better, to return it to the esteem the Azims had held for it?

Tareq cried in the car.

For him, what became as vital as reclaiming the parcels of land was improving the lives of the people who lived near them. In Kabul, Tareq befriended 12- and 13-year-olds and one day took them for ice cream. The kids stopped before a certain block -- Block 12 in Tareq's nomenclature, because the city was too bombed out for street names -- and said they couldn't walk farther. A rival gang controlled that street. Cross it, and gang members might bomb your car or throw Molotov cocktails through your apartment window.

Azim had a thought. The only way people listened to each other, the only way people had listened to him, as an immigrant in Concord, was through the language of sports. If he could get the kids to communicate, he could perhaps stanch the flow of blood.

That's how Azim came to set up a neighborhood soccer league, which often played its games within view of Block 12. The Block 12 kids, curious, edged closer to the field of play until, one by one, they joined in. The league spawned from there. Neighborhoods taking on other neighborhoods, girls joining the games, Azim going door to door to explain to parents -- who'd lived through the '90s and the Taliban's edicts against music, singing and women's rights -- about the benefits of a sport like soccer. Through these conversations, Tareq heard of a man named Abdul Saboor Walizada, who'd started a separate girls soccer league in Kabul. Azim teamed up with Walizada. The girls laughed at their new, obviously American coach, who didn't care about the cultural norms that stated men couldn't talk to women who weren't their wives or sisters. Azim talked with anybody, in Dari or Pashto or English, if the girls knew it. He encouraged them on the pitch, joked with them off it, and the new girls league took off, with divisions and age ranks. Suddenly neighboring provinces wanted in. Azim had planned to stay in the country a month, and here it was a year later and the work as Walizada's deputy consumed him. He traveled, he cajoled, he carried out administrative duties until it was no longer a girls league at all but a nationally sanctioned women's soccer federation. It spanned a handful of cities and 25 teams.

"I used to stand and watch soccer and think, 'Maybe in an afterlife I could play it myself,'" says Shamila Kohestani, the first captain of the Afghan women's national team. "It was a great thing ... to finally have a place where we were accepted as athletes."

And then, in 2006, ESPN called. Girls aligned with the emerging national team had just won the Arthur Ashe Courage Award. Could a few players and Azim and Walizada fly to Los Angeles, to be honored at the ESPYS?

Tareq, training young female boxers in Afghanistan, circa 2007. Courtesy Tareq Azim

AFTER THE AWARDS ceremony and parties, and after the seven other Afghans exhausted their questions about America, Azim returned to Afghanistan. It felt increasingly like home. Yes, he'd negotiated with warlords to reclaim his father's land and, yes, violence remained as ubiquitous as the country's corruption, but Afghanistan wasn't just radical mullahs, death and bribes either. Here he could continue to change perceptions. Here he could lay bricks, and maybe build something of his own, something even more impressive than the soccer federation.

He had a second, bolder thought. If the maxim were true that empowering a woman liberated a family, what if Azim literally made Afghan women as powerful as men?

What if he taught them to box?

His friends and extended family said it was a terrible idea. Even his mother, the one whose lay bricks mantra and strong will lived in Tareq's favorite photo -- an image of a radiant Mina, enjoying a cigarette in Kunar, next to her AK-47 -- even she thought Tareq had gone too far this time. In certain provinces, "People don't want girls to go to school," she told him. "How will you convince them to let girls box?"

Tareq's mother, Mina, enjoying a smoke in the Kunar province of Afghanistan. Courtesy Tareq Azim

Still, he couldn't let the idea go. Its bright promise lit his days. The confidence he'd had as a young boxer- -- what if women here had that? So how to convince everyone? Well, Afghanistan ran on tribal politics. Azim would simply have to paint for the largest tribal rulers a portrait of the future he saw. He isolated three leaders, the most menacing of whom was Mullah Wakil Ahmed Muttawakil, a high-ranking Taliban politician and former spokesman for the regime's brutal supreme commander, Mullah Mohammed Omar. If a Taliban official endorsed Azim's idea, who could be against it?

President Hamid Karzai's government had at one point placed Muttawakil under house arrest for the bloodshed he'd ordered or condoned, a predicament that did not necessarily limit Muttawakil's influence within the Taliban. Through Azim's growing Rolodex, he discovered Muttawakil lived now in a guarded compound on the western edge of Kabul.

Azim didn't tell the American embassy about his plans, much less his family, but did agree to a request from a documentary film crew, which had learned of Tareq through the ESPYS and wanted to follow him now. One day Tareq and Peter Getzels, a producer and director from Washington, D.C., headed out to meet Muttawakil.

They drove to a mountainous nowhere-world 25 minutes outside downtown Kabul. Amid this moonscape they saw men with assault rifles guarding a small compound.

Wild thoughts ran through Azim's head: What if it all went wrong and he and Getzels were shot in the back? What if they were disappeared? At the same time, an equally delirious confidence buoyed him: He could do this. He'd done it before; he'd just been honored for doing the "impossible."

Besides, he thought, the plan had to work. The one thing he'd intentionally left in Kabul was a gun.

He and Getzels were led to a room with red carpet and love seats. Muttawakil appeared, bearded and bespectacled and soft-bodied, in flowing Afghan garb. He looked more like an imam than a hardened political killer.

They sat down. "I played sports in America," Azim said in Pashto. He had given this moment a lot of thought. "I understand community. I understand unity. I understand the power of sports. It's just not right that our kids don't have opportunities -- or [aren't] able to learn about themselves, [aren't] able to build confidence..."

Muttawakil nodded. The suspicion in his face softened just a bit. The pair traded anecdotes about Afghanistan and Islam in Dari and Pashto. One hour passed, then two. Azim's fear transformed little by little into something like hope as they moved into their third hour. Muttawakil said the Taliban, despite its reputation, wanted social progress, and so would not interfere with Azim's wishes or harm him personally. He asked only that young women follow Sharia law and dress conservatively: no sports bras in the ring. Azim agreed. Muttawakil put his hand on Azim's and said the female boxing program would be a "symbolic" testament to a new Afghanistan. "Go," he said, his face alit.

Azim opened the first gym on the grounds of Ghazi Stadium in Kabul, where the Taliban in the '90s had beheaded dissidents. He wanted "to prove to the world that Afghanistan is ready for social change."

Without the aid of foreign governments or the guidance of NGOs, he worked with provincial governors and everyday Afghans to help open 36 more gyms, with around 250 girls and young women training and sparring regularly. One of them, Sadaf Rahimi, became the first female boxer in Afghanistan invited to the Olympics. "I wanted to prove that Afghan girls could do everything, too," she told the international media.

It should have been a fairy-tale ending. But 10 days before the London Games, the International Boxing Association revoked Rahimi's Olympic invitation, citing a curious claim about her lack of preparedness. (Azim thought the revocation had more to do with Afghan politics and the anger from hard-lined conservatives that the boxing program had induced.) Even before the Rahimi mess, Azim saw the boxing federation fall prey to what-about-me infighting and petty corruption. "It broke my heart," Azim says. "When all that hijacking s--- began, I learned to not think that anything [in Afghanistan] was mine."

He realized that perhaps only in the States could his bricks build a lasting structure.

Marshawn Lynch, center, in the Empower gym with trainer Johnny Ricci, left, and Azim. Talia Herman for ESPN

WHAT STAYED WITH him when he returned to the Bay Area in 2008 was that meeting with Muttawakil. He, Tareq Azim, an American civilian, had actually met with a leader of the Taliban -- unarmed! -- and gotten the guy to bless his progressive idea. Azim had found a way to stare through his fear and accomplish something not even his mother thought possible.

What else would people do when fear no longer bound them?

He worked in various Bay Area gyms to test this question, and little by little his client list grew until it included MMA champion Jake Shields and football players from Oakland, Raiders QBs Charlie Frye and Bruce Gradkowski. They each found that the inaugural session with Azim did not cover the proper form on bench press. It was a sit-down that went something like this:

Azim said they had a "disease of fear." To move past it, he told his athletes to first imagine the worst that could happen to them now, today. Invariably the athletes said they could die. Azim told them that they'd die anyway and that they needed to prepare for it, much as he had in Afghanistan. By preparing for death, they could fully realize the gift that was life, and live as fully realized people, not just myopic professional athletes. None of this would be easy. To move beyond fear, they -- tough NFL players and combat sport pros -- had to first acknowledge they were fearful, which meant allowing themselves to be vulnerable, which meant being honest with themselves and everyone who walked into the gym. And if they sought this level of truth, they could, as the Quran put it, be excellent in everything they did.

Gradkowski and Frye were in awe. They went back to Raiders coach Tom Cable: You gotta meet this dude. Cable did. No one in the NFL talked like this. Azim was training so much more than players' bodies. Word spread along the West Coast and ultimately reached the Seahawks coaching staff. They had a running back who was underperforming. Perhaps that guru guy in San Francisco could help.

Azim had opened his own gym, Empower, and within 30 minutes of Marshawn Lynch meeting him there, Lynch pounded his chest and declared, "My brother!" The socially conscious Lynch already was living what Azim was preaching, so of course he would follow The Game Plan, what Azim's acolytes now called the personalized goals that emerged from that first sit-down. Over the coming seasons, the trainer who was more than a trainer helped pull out the All-Pro within Lynch. That left hook of a stiff-arm that went viral against the Niners' Patrick Willis in 2013? Born out of the boxing Lynch and Azim did in Empower.

Lynch's trip to Haiti in 2016, to provide relief after the country's massive earthquake? Lynch had always been charitable -- that's why he and Azim clicked -- but the trainer says, "I try to normalize all the not-normal dreams of athletes." The pair got so close that Marshawn began to refer to Sayed Azim as "my dog," so close that when Lynch needed hernia surgery in November 2015, Tareq dropped his holiday vacation plans and rehabbed Lynch every day for two and a half weeks, through Christmas and New Year's, to get the running back ready for the Seahawks' playoff game against the Panthers.

"Tareq wants to be the one to take on the brunt of other people's problems or issues," says his wife, Megan, who met Tareq in 2012, as Empower started to draw the attention of Lynch and other stars like Justin Tuck and Barry Zito. "And Tareq also wants to be the one who alleviates any of those situations."

One pro would test him more than any other.

Azim and Lynch, in Tareq's office at Empower. Talia Herman for ESPN

WHEN AZIM "GAME PLANNED" Dion Jordan in the summer of 2015, "You could tell he was broken," Azim says today. "You could tell he hadn't loved himself for a long time." A lot of athletes hung at Empower before or after their workouts, but Azim mandated it of Jordan. "With Dion it was an eight-hour shift," Azim says. Get to the gym at the start of business. Attend meetings with Azim, "just to hear what's up: how I sell, how I work, how I build relationships." Then train. Get massaged and stretched. Lunch. AA. Then back to Empower for more meetings. "The gym was like my second home," Jordan says. As the weeks turned into months and then into years, Jordan chose as his actual home a rented apartment just down the street from Empower.

"With Dion," Azim says, trying to find the words, because while he has a familial relationship with his athletes, something else developed with Jordan, "his level of dependency and appreciation helped me feel really valuable." Here at last was the calling equal to Azim's ambition, equal to his desire to give and not have the results ruined by outside forces. Getting Jordan back to the field -- it was almost as if Azim had found his life's work.

“I try to normalize all the not-normal dreams of athletes.”

- Tareq AzimThe bond deepened. Azim said they had to do a good deed a day. One afternoon he and Jordan went to Subway and bought 100 sandwiches and drove all over San Francisco, delivering them to the homeless. They read a chapter of a book each day. One of their favorites was "Purification of the Heart," a treatise by Islamic scholar Hamza Yusuf. "We of the modern world," Yusuf wrote, "are reluctant to ask ourselves -- when we look at the terrible things that are happening -- 'Why do they occur?' And if we ask that with all sincerity, the answer will come resoundingly: 'All of this is from your own selves.'" Azim asked Jordan to visualize his return to the NFL, a once laughable premise -- the world outside Empower saw Jordan as perhaps the biggest bust in league history -- but it was an idea that became more rooted in reality with each passing day. "Set the tempo and the standard for your first game back," Azim told him. "What will it feel like when you get a sack?

"Everyone will know who you are."

Jordan smiled. "It's a daily challenge to be better," he says. "To be a great son, brother, boyfriend ... but I've learned that's the stuff that's worth it."

Azim wasn't surprised when the Seahawks acquired Jordan before the 2017 season. Knee injuries derailed the defensive end's debut, but when it came, in Week 10, the venue seemed fitting: in Arizona, against the Cardinals, 30 miles from that darkened home that Jordan had once refused to leave. Midway through the fourth quarter, Jordan bull-rushed Cardinals left tackle John Wetzel and knocked him flat on his ass, then pulled down quarterback Drew Stanton for the sack.

"It has been the longest of long roads," NBC analyst Cris Collinsworth said on air.

After the game, on the charter bus, Jordan took out his phone and FaceTimed Azim. The trainer could barely make out Jordan's face, the bus was so dark, but he could see Jordan's smile.

"We did it, T. We did it."

The walls of Azim's office are adorned with jerseys of the athletes he has trained over the years. Talia Herman for ESPN

AZIM SITS AT his desk, hunching over his laptop in the mesh shorts and T-shirt that are his business attire, when his phone chirps with another request to FaceTime from Jordan. It's Wednesday afternoon, one day after my workout with the pros and a few hours after a high school football team trained under Azim, and Marcus Peters told the panting players as they recovered to "get uncomfortable."

"Wassup, bro!" Azim says now to Jordan, who on the screen is shirtless and seems to have not long ago finished his own workout in Seattle.

Jordan smiles. "Sup!" They've already talked once today, when Jordan relayed the news that the NFL had decided to no longer randomly drug test him, another sign of how far he has come since 2015.

Both men would love nothing more than to be together every hour in these last days before training camp. A month earlier, as the Seahawks wrapped their spring organized team activities, Azim floated the idea of Jordan staying in Seattle for a few weeks. "Let them know what I know," he'd said. Jordan had finished 2017 on a tear-four sacks in five games-but if the Seahawks coaching staff had doubts about the sustainability of this new Dion Jordan, "Let them fall in love with you too," Azim told him. "Let them respect you. Let them believe in you."

So Jordan had stayed in Seattle -- but the dependency had continued. He messaged with Azim all the time. Azim loved it as much as Jordan did. Minutes before Dion FaceTimed him, Azim had said to me: "Obviously my ego and just my desire of wanting to be around my people, I'm like, 'F---. I wish he was here.'" He said he was looking forward to Friday, when Jordan would fly back to San Francisco to finish his summer training at Empower.

On FaceTime now, though, Jordan is anxious. There's something he wants to broach, but it takes a while to say:

He doesn't know if he should come back to Empower this weekend.

"Oh," Azim says.

Jordan backtracks. He will if T wants. It's just the tight schedule ... and then Jordan is stumbling again, unsure of himself. "What do you think?"

The prospect of not seeing Dion before the season stings Azim. As Jordan's consigliere, though, the question is frustrating. Jordan has to start being the CEO of his life. They've talked about this.

"Well, what do you think?" Azim asks.

Jordan mutters something about logistics and difficulty and then in his restless anxiety is a plea they both understand: If you want me down there, T, just say the word.

"Stay up there," Azim says, trying not to grimace.

Since they won't see each other for a while, Azim asks if anything ails Jordan.

"My knee," he says. He had a minor surgery two months earlier and complains now about his "get offs": a 50-yard, down-and-back run used to test quickness and agility. Jordan sends Azim a video of one such run. He wants to know if, on that corner turn, his knee is "firing" correctly.

Azim watches the video. "Dude, you look great on film." After a moment: "Is it physical or mental?"

Azim suspects it's mental.

"It's physical," Jordan says.

"All right," Azim says, not believing him, but wanting to see if Jordan can stare through this fear about his knee -- probably a proxy for his fear about remaining in Seattle this week -- and find his way to the answer, a fragment of a deeper truth that keeps alluding Jordan.

"Walk me through why it's physical."

Jordan says he feels it could be in his hips.

Azim nods his head. "Have you been doing your hip activation?" It's a series of movements -- a workout, actually -- to get Jordan's legs moving with no wasted effort.

Jordan says he hasn't been doing it as often as he should.

"So it sounds like there's a lot more on your knees," Azim says, "because your hips aren't cooperating with your feet."

"Yeah, you're right," Jordan says, liking that answer.

Azim stares at Jordan. He gives away nothing.

In the end, bricklaying is a funny business. For three years, you can stack bricks with someone you love. But as the edifice rises before you, the best you've ever built, you realize the building that will matter more is the one your friend has yet to construct, alone.

Azim lets the moment drag out.

Jordan frowns. "I also got to get it in my head that I'm fine."

Azim tries to stay as calm as he can.

"OK, cool," Azim says at last, in a voice he hopes is level.

Moments later he signs off with Jordan, and smiles.