I will tell you up front (at the risk of making you close the tab, but honesty and humility are in part the subject matter here): This may be the least sexy movie-star profile you will ever read. Because you know that thing where you meet a movie star and right off you bond over taking your high-school-aged kids on college tours? No, I don’t know that thing, either.

But it’s what happened when I met Steve Carell this past summer. He had spent much of the year with his seventeen-year-old daughter, visiting prospective schools around the country. I recently went through that process with my own two children. So, as is often the case with middle-aged parents in coastal enclaves, we began lamenting the professionalization of the admissions process, the way so many families now hire test-prep tutors and essay coaches and interview consultants, and the awful stress that puts on kids who, being teenagers, already have enough to worry about without having to deal with the drudgery and anxiety of applying to twenty colleges. (No joke: That’s practically a norm in the 2010s.)

“It’s a science now,” Carell, who is fifty-six, marveled. “It’s very different than when I went to high school. I had a list of, like, four colleges, and I applied and I went to one. I didn’t put that much thought into it.” Me neither, with my three-school lottery back in the mid-1970s. We agreed it was a parent’s job to keep the kids from coming unglued or turning into monstrous, Ivy-seeking missiles, to reassure them that they’ll get in somewhere and that, more likely than not, they’ll have a great time at that somewhere—and if not, they can always transfer.

Sound parental counsel. As I said, this may be the least sexy movie-star profile you will ever read.

To some degree, that is because Carell himself may be the nicest guy in Hollywood, as attested to by two decades’ worth of costars, colleagues, and interlocutors. He has certainly played some of the nicest characters in recent movie history, ranging from the open-hearted title character of The 40-Year-Old Virgin, to the more experienced but still lovelorn single men of a certain age in Dan in Real Life and Crazy, Stupid, Love, to the grief-stricken fathers in last year’s Last Flag Flying and the just-released Beautiful Boy.

Even his more “problematic” characters—say, Michael Scott, the doltish boss he portrayed for seven seasons on The Office, or emblematic male chauvinist pig Bobby Riggs in last year’s Battle of the Sexes—offer glimpses of vulnerability that make them likable in a weird-but-he’s-my-cousin way. Add to this roster Gru, the supervillain he’s voiced in the animated Despicable Me movies—a decent chap and an attentive dad. The outlier in this filmography would be John du Pont, the jealous, murderous wrestling patron in 2014’s Foxcatcher, Carell’s first outright drama. The role, for which he wore a startling prosthetic beak, changed many people’s perceptions of what Carell could do and earned him a well-deserved best-actor Oscar nomination. But even du Pont, while grotesque, possessed a recognizable, even tragic humanity; in Carell’s interpretation, you sensed sickness more than evil.

Carell was just getting back to work when we met. He had spent most of 2017 shooting three movies more or less back to back to back, wrapping the last one right before Christmas. He then took off most of 2018—he “just wanted to hang around” with his family—before preparing to dive into this fall’s festival and awards circuit, during which all three of those films, very different from one another but equally ambitious and all based on true stories, will possibly be in contention for various statuettes. In rapid succession you will have the opportunity to see Carell as a father struggling to understand and help his drug-addicted son in Beautiful Boy; as a brain-damaged trauma victim who copes with his emotional wounds by re-creating World War II battles with Barbie-like dolls in Robert Zemeckis’s Welcome to Marwen (December 21); and as former secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld in Adam McKay’s Dick Cheney biopic, Vice (December 10).

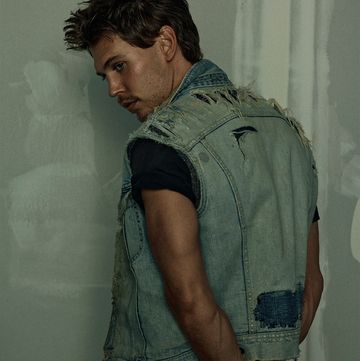

Rumsfeld may seem an unlikely role for Carell, but one thing the two men seem to share is an indifference to the spotlight—an odd trait in actors and politicians alike. Carell might be the least needy performer I’ve ever met. With glasses and a thick but neat beard, and dressed in a navy-blue crewneck sweater over a crisp white shirt, he looked like one of the admissions directors he could have encountered on a college tour; a thoughtful, soft-spoken demeanor added to this impression. “I don’t think I’m a very scintillating conversationalist,” he told me, which is untrue but telling.

Comedians are notoriously—or perhaps stereotypically—driven by childhood scar tissue. But Carell is famous among his peers for keeping that scar tissue, if there is any, deeply hidden. As Jon Stewart, his friend and former boss, told The New Yorker several years ago, “Maybe Steve’s lack of wound is his wound.” Or maybe, decades’ worth of biopics of artists and musicians notwithstanding, being well-adjusted is an asset rather than a hindrance to creativity. (See: Meryl Streep, Paul McCartney.)

At Carell’s suggestion, we met at the Smoke House, a red-banquette restaurant in Burbank that has sat across the street from the Warner Bros. lot for more than seven decades, a sign outside still promising “Fine Food at a Fair Price.” The menu is full of classics such as shrimp Louie and a French-dip sandwich (there’s a prime-rib special on Mondays), and the waiting area is adorned with pictures of now-dead patrons, including Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, Steve McQueen, Lee Marvin, and Danny Kaye. Aside from Carell, this noontime’s clientele was decidedly less starry—a pleasant middle-class lunch crowd, mostly locals, a few tourists. The Smoke House is also, coincidentally, where my two sets of grandparents met for the first time, in 1951, following my parents’ engagement. I mentioned this to Carell as we settled into a booth. “I guarantee you, it hasn’t changed at all,” he said. He’s probably right. The restaurant had a slightly dusty, yeasty, beefy aroma reminiscent of 1951, or so I’d imagine. “We come here from time to time,” Carell said. “I kind of like that it hasn’t moved an inch.”

“We” is Carell; his wife, Nancy Carell; their daughter; and their fourteen-year-old son. The restaurant is only a short drive from the family’s home in Toluca Lake, one of the quieter neighborhoods in Los Angeles, a tony but unflashy corner of the San Fernando Valley. “There’s not a lot going on,” Carell said, almost apologetically. “You can go for bike rides with your kids and stuff, so it feels pretty suburban given that we’re in a city.” He added that he and Nancy—who, like him, grew up outside of Boston—naturally gravitated to the Valley when they first moved to L.A., in 1996, and rented a house in Sherman Oaks. “It just felt very neighborhoody, and there wasn’t a lot of pretense, so it was nice.”

Nice place. Nice guy. Fine food. Speaking of which, if Jimmy Stewart hangs on the wall at the Smoke House, I missed him, but he might serve as an old-Hollywood antecedent for Carell: a star who could do both light comedy and drama, and who also projected regular-Joe decency. Isn’t Mr. Smith Goes to Washington just a black-and-white precursor, with a filibuster, to The 40-Year-Old Virgin? And if you are a contemporary studio executive who is reading this and thinking of remaking Harvey or It’s a Wonderful Life or Vertigo—well, don’t. If you remain dead set on the idea, though, don’t just assume you’re going to cast Tom Hanks. Am I crazy to think a Rear Window with Carell opposite Amy Adams or Tiffany Haddish might even be kind of good?

But let’s talk about actual Carell movies. Beautiful Boy is adapted from parallel memoirs by father and son David and Nic Sheff—the former a magazine journalist (Rolling Stone, Playboy), the latter a recovering addict turned writer. I admire the film immensely for offering no easy solutions to addiction, and for being brave enough to give the fleeting pleasures of drug abuse their due; it’s a tough watch at times but couldn’t be more germane, with the opioid crisis gutting communities across America. Costarring as Nic, who was hooked on methamphetamines, is Timothée Chalamet, the floppy-

haired twenty-two-year-old who broke through last year as a kind of thinking teenager’s heartthrob, playing Saoirse Ronan’s poseur boyfriend in Lady Bird and the lead in the coming-of-age love story Call Me by Your Name, opposite older man Armie Hammer.

Chalamet and Carell developed something of a father-son dynamic both off screen and on, as the director, Felix Van Groeningen, had calculated they might. “That Steve is a very devoted family man was very important” in casting him, said Van Groeningen, a Belgian making his first American picture. “Who people are in real life and who the character is obviously don’t have to match, but for this role I wanted the actor who was going to play it to keep it very close, for it to come from a very honest place.”

One example: To depict Nic Sheff in the deepest, most strung-out throes of addiction, Chalamet, slender to begin with, went on a controlled diet after the cast had finished a long rehearsal process. According to the actress Maura Tierney—who plays David Sheff’s second wife and Nic’s stepmother—when Chalamet first showed up on set several weeks later, “I remember Steve going, ‘Oh my God, he’s losing weight!’ in a very dadlike way. Their relationship was really like that.” Carell told me that his unfeigned dismay at Chalamet’s appearance that day—“He just looked terrible with the added makeup, like really shockingly bad”—kickstarted one of the film’s most wrenching scenes.

Carell also drew on childhood memories of his own father: “My dad, who is about to turn ninety-three, is a real rock. A real stoic. He didn’t cry a lot, but I could tell when something was tearing him up inside. He internalized it for the sake of the family. And that to me was more heartbreaking than someone who would just, you know, be really outward with his emotions. It’s kind of how I interpreted the David character: He’s trying to keep it together.” Wrestling with the limits of David’s love for his son, its impotence in the face of Nic’s addiction—the film has a distinctly un-Hollywood message, that love sometimes isn’t all you need—Carell does some of the best, most controlled acting of his career, often without words. You can see the resignation in his body as he takes down a picture of Nic from a wall in his study; and the tentativeness, in the final scene, with which he puts an arm around Chalamet’s shoulder—a broken bond beginning to mend. If you are like me, at that moment you may get teary, and you may even forgive the movie for scoring an earlier scene with “Sunrise, Sunset,” that schmaltzy Fiddler on the Roof bar and bat mitzvah perennial. (“Is this the little girl I carried...”)

So much talk of fathers and children made me curious: Are Carell’s kids Carell fans? Do they watch his movies and binge seasons of The Office? Or does he try to keep them away from all that? “They keep themselves away,” he said, laughing. “I’m just a dad to them. They obviously know what I do, but we don’t put a lot of value on that. From time to time, they’ll check out my stuff, and they hear about it at school a little bit. But it’s just my job.” (I suppose I might have avoided The 40-Year-Old Virgin, too, if it had starred my dad.)

The stoic father Carell mentioned was a businessman and an electrical engineer; his mother was a psychiatric nurse. He grew up in Acton, Massachusetts, as the youngest of four brothers. He did some acting in high school and in college, at Denison, from which he graduated in 1984 with a double major in history and theater. But he never really thought of himself as a performer, or of acting as a possible career, until he was applying to law school like any other liberal-arts major unsure what to do with himself. Indeed, he evinced so little enthusiasm for attending law school—he got stuck on the question, on one of the applications, “Why do you want to be an attorney?”—that his parents suggested he “name something you’ve always enjoyed.”

The answer, Carell realized, was acting. He eventually moved to Chicago, figuring it would be more hospitable for a raw young performer than cutthroat New York or Los Angeles. He was right, or at least Chicago was right for him, and he began getting small parts in shows and commercials. (On YouTube, you can catch him in a 1989 ad for Brown’s Chicken: “While we’ve always cooked our chicken in cholesterol-free cottonseed oil, we now have cholesterol-free batter, too!”) In 1987, he joined the legendary improv institution Second City, at which he overlapped with Stephen Colbert (his understudy for a time), Tina Fey, and Adam McKay. He also met his future wife, then Nancy Walls, at Second City; she was a student in an improv class he taught who would outpace him early in their respective careers when she landed a slot as a cast member on Saturday Night Live in the 1995–96 season. (Today, Nancy works as a producer; she and Carell coproduce Angie Tribeca, a TBS comedy series starring his former Office castmate Rashida Jones.)

Carell got his own break not long after Nancy’s when he was cast, along with Colbert, on Dana Carvey’s short-lived (but beloved by comedy geeks) prime-time ABC sketch show. In 1999, on Colbert’s recommendation, he was hired on Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show, where he served for six years as a goofily enthusiastic correspondent.

He won attention from critics and audiences for supporting roles in Bruce Almighty (2003) and Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy (2004). On the set of the latter, Carell met Judd Apatow, a producer on the film, who invited him to get in touch if he had any good movie ideas. Carell thought he did. “So I went into Judd’s office and I pitched him an idea. We talked for an hour and a half and, you know, he thought it was fine.” Fine, Carell’s tone suggests, as in only okay. “And just as I was getting up, I said, ‘Oh, and there’s this other secondary idea about a guy who’s never had sex.’ And Judd sparked to that immediately and said, ‘I can sell that to Universal tomorrow.’ And literally the next week he mentioned it in passing to an executive at Universal and they bought it on the spot.”

With Carell and Apatow cowriting the script and Apatow directing—it was his first feature—The 40-Year-Old Virgin became a huge hit, buoyed by Carell’s earnest, sweet-natured performance and his easy chemistry with costar Catherine Keener, which grounded the wilder jokes and relocated the unlikely premise somewhere near believability. Yet Universal, perhaps suffering from buyer’s remorse, had shut down the production after its first week of shooting because the studio’s executives were concerned that, as Carell put it, “the dailies of my character just looked too creepy. They said I looked like a serial killer.”

He and Apatow assured the studio they just hadn’t gotten to the scenes with heart. The thing would work—promise! But others had doubts, too. “I had a high school reunion just before the movie came out,” Carell said. “I hadn’t seen these people in several years. And they’d start talking about what they’d been involved in, and I would mention that I just did this movie called 40-Year-Old Virgin, and as I reflect back, I realize how dumb it must have sounded to all of these people. It sounded like it might be the worst movie ever, just based on the title. I could feel my classmates feeling sorry for me. I could see the pity in their eyes.”

Starring on an American remake of The Office, Ricky Gervais’s mean-spirited, cult-favorite British TV series, was another career move that didn’t necessarily look great on paper. Fans of the original rolled their eyes, and the first season debuted on NBC in March 2005 to mixed reviews and indifferent ratings. It was the prerelease buzz for The 40-Year-Old Virgin that helped persuade the network to renew the show for a second season. With Carell now something of a household name and the series finding its creative sea legs, The Office would double its ratings in season two and win the Emmy for outstanding comedy series, while its star would receive the first of six nominations—inexplicably, he never won—for lead actor in a comedy series.

In between seasons, Carell shot a number of broad movie comedies, including Evan Almighty (2007), Get Smart (2008), and Date Night (2010), which all did okay at the box office but weren’t nearly as interesting as what he was doing on TV. He wasn’t slumming, but he wasn’t moving the needle on his career, either. To hear him tell it, however, that career was something of a left turn in the first place. Unlike a lot of comedians and comic actors, Carell insists he didn’t grow up desperate to get laughs. He wasn’t even a particular fan of the genre as a kid, though he did love listening to comedy albums. “Especially George Carlin and Steve Martin—over and over I’d listen to those routines. I think what I didn’t realize at the time was that I was studying. I was trying to understand what made them funny, why I enjoyed it so much, what they were doing with the language, what they were doing with the misdirection. Steve Martin in particular, his brand of comedy was so different and so absurdist that I really took to that immediately. But I never thought of myself as particularly funny.

“When I moved to Chicago, I didn’t aspire to be a comedic actor,” he continued. “I just wanted to work, and those were just the jobs I tended to get more often, the comic parts. I kind of ended up doing it out of necessity.”

I asked why he thought he got those roles. “I don’t know.” He paused, mulling it over. “I clearly did better at that than the straight stuff. I think there are generally more actors who audition for straight roles, so just by the odds, I think you have better odds going for a comedic role because some people are afraid to try it.” He paused again. “I don’t know. In Chicago, I just kind of fell into that community. I wanted to get experience. I wasn’t too concerned about how I was going to be labeled. I was just interested in working.”

I wondered whether there was something binary in his approaches to broad comedy and drama—if he was drawing on different sides of his brain, as it were—or whether there was more of a continuum in his approach, no matter the material. “That’s an interesting question,” he replied hesitantly, as if he hadn’t considered it before (or kindly wanted me to believe he hadn’t). “I think it’s sort of the same. Whether a character’s super-broad or incredibly internalized, the most important thing to me is that some sort of honesty registers, that you can tell that these are human beings.” He put on a mock-serious voice: “That is my goal: to depict someone that falls within the realm of human being.” He laughed, then turned genuine-serious again. “You know, you do your research. You think about backstory. Even the silliest characters or the darkest characters or even the most insidious characters, there’s lots of different components to them that you don’t necessarily have to say out loud or have register in a movie, but they should be present somewhere. I think about Peter Sellers and how he was able to do those incredibly broad characters, but at the same time you always knew that it was a person. Clouseau”—Sellers’s bumbling inspector from the Pink Panther movies—“was a real person. He was absurd, he was silly, but he was going through something. To me, that character was all about a man retaining his dignity, and that felt very honest and truthful to me. Hence all the stuff he did was that much funnier because you felt like you were watching an actual human being going through human emotions.”

He brought up Michael Scott and how he had worked to give the character a well-meaning if oblivious side to anchor the comedy of boorishness. “I know people like that who really, through no fault of their own, can be off-putting, but at the same time I know them to be good people. That’s what we were going for with Michael. I just thought, He’s a pretty complicated guy—a lot of different facets to him.” Similarly, he said, he had worked hard to locate a “sad story” somewhere in John du Pont’s psychological makeup.

Well, then: What was the backstory for Brick Tamland, the earnest, deranged, possibly brain-damaged weatherman Carell played in the two Anchorman movies? He laughed. “The whole interview should be about what’s Brick’s story. Brick might be the anomaly. I think the less that’s revealed about Brick Tamland, the better. Brick can get away with doing anything because there’s no frame of reference to his life in any way. So he can appear at his own funeral, or he can just pull out a gun from the future or be holding a hand grenade for no good reason. Characters like that are really fun because they’re just such wild cards. On Anchorman, the first one, I had almost no lines. I was obviously a member of the news team, but Adam McKay”—the director of both—“would tell me to just make a comment at the end of the scene. And I’d say whatever came to mind. And generally it wasn’t related at all to what was going on. It was some sort of flight of fancy in this guy’s head.” But Carell blurted those lines with such conviction that you believe Brick when he declares, “I ate a big red candle” or, in an outtake appended to the credits, “I pooped a hammer.” It’s funny because it seems true.

Brick aside, my own favorite Carell performance is Bobby Riggs in Battle of the Sexes, a film that deserved to be more widely seen. (Carell allowed that he agrees.) If Riggs’s greatest contribution to history was serving as a foil to Billie Jean King, his second greatest was providing a vehicle for the full breadth of Carell’s talent. He inhabited Riggs’s clownish but cunning public persona with a comic brio equal to the original’s, while shading his offstage moments with doubt, melancholy, and a more self-aware kind of cunning—a buffoon in full, and an unexpectedly moving one at that.

Welcome to Marwen is another film taking full advantage of Carell’s binary/not-binary skills. Based on the critically praised 2010 documentary Marwencol, the new movie tells the true-ish story (Hollywood true, let’s say) of Mark Hogancamp, an artist who lives in upstate New York and who once specialized in World War II illustrations. In 2000, however, he became the victim of a vicious hate crime when he was badly beaten up in a bar fight and left for dead in the parking lot by five men who singled him out because they had heard he was a cross-dresser. He survived after nine days in a coma but lost most of his memories along with his ability to draw. Needing a new creative outlet, Hogancamp created a 1:6 scale replica of a World War II–era Belgian town in his backyard that he populated with dolls representing women he knew, as well as an alter ego, Captain Hoagie; he added Nazi dolls to represent his attackers and arranged the whole cast in tableaux for photographs—not only a new medium but also a kind of ad hoc psychotherapy, an adult version of a kid reenacting trauma with dolls in a child psychiatrist’s office. Hogancamp’s artful pictures of what he called Marwencol eventually found their way to galleries. (I’d explain the discrepancy between Marwencol and Marwen, but that would be something of a spoiler.)

Welcome to Marwen bounces between a straightforward depiction of Hogancamp’s somewhat precarious day-to-day existence and fantasy sequences reflecting his interior life, in which the dolls (played by Carell and fellow live-action castmates, including Leslie Mann and Janelle Monáe) are animated through the motion-capture technology Zemeckis helped pioneer in films like The Polar Express and Beowulf. The fantasy sequences have a deliberately campy, comic edge, and the tonal shift is what led the director to cast Carell. “I needed someone who was a great actor, someone who could evoke emotion and pathos playing a damaged, broken character suffering from PTSD,” Zemeckis told me. But he also required a performer who could affect “all this World War II–movie swagger” for the Barbies-at-war scenes. “I needed an actor who could do both,” he said, “and Steve fit the bill perfectly.”

I saw an unfinished version of the movie, and I think it will appeal in particular to fans of Zemeckis’s Forrest Gump—a very different movie, but one that’s tonally and thematically similar to Welcome to Marwen. As in Beautiful Boy, Carell does some subtle but affecting physical work. There are moments when you can see the accumulated emotional pain of Hogancamp’s trauma weighing down on Carell’s shoulders as he walks away from the camera, and the legacy of physical therapy in each deliberate step. “That’s the stuff of a great actor,” Zemeckis said. “He transforms his entire physicality.” Yet there’s nothing showy about Carell’s performance, in a role that other stars who started out in silly comedies might have gone “full Patch Adams” with, to misquote Tropic Thunder.

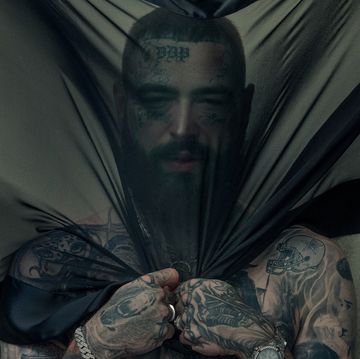

Vice follows Dick Cheney’s career over several decades. It will be Carell’s fourth movie with McKay, after the two Anchorman films and The Big Short. (I wish the filmmakers had stuck with the snarky working title, Back Seat—as in driver.) The cast includes Christian Bale as the former vice-president, Amy Adams as Lynne Cheney, Sam Rockwell as George W. Bush, and Tyler Perry as Colin Powell. Carell showed me a picture on his phone of himself in makeup as Rumsfeld, and the transformation was astonishing: If he didn’t look exactly like the former secretary of defense, he looked like Rumsfeld in an odd, slightly unrepresentative photograph, or maybe Rummy on a day when the air conditioners have broken at Madame Tussauds.

This role might be the greatest challenge yet to Carell’s ability to plumb character and find a little human something or other deep inside that actually bleeds—but as Rumsfeld himself once said, you go to war with the army you have. “I went into it thinking, Here’s a man, a very smart man, who is clearly flawed, but he also believed what he was doing,” Carell told me. He read as much as he could about Rumsfeld—biographies as well as Rumsfeld’s own books. (He’s written two memoirs and a book of “leadership lessons.”) “People have an idea about Rumsfeld, but it’s a very narrow idea. I felt like it was my job to expand that and paint a broader picture of who he was, what he feared, what was upsetting to him. It’s easy to just play a caricature or watch some film clip and then say, ‘I’ll just do that.’ It’s a little cavalier to say that I understand what makes Donald Rumsfeld tick, or John du Pont. But I’ve made an attempt. You do the best you can with the material you have, with the sources you have, and with your imagination.”

What would be the logical end point of that challenge? Could he, would he, play... Donald Trump? Could he find the humanity beneath the laughable hair, the revolting racism and sexism, and the predatory personality disorder? (That is my characterization; Carell doesn’t broadcast his political views, though he did make a campaign appearance for Hillary Clinton in 2016.) He thought it over for a moment. “You hope you can find the humanity in anybody that you play,” he finally said. “If I couldn’t, then I wouldn’t play that part. If you go into a part with complete disdain and find no nugget of humanity in a person—I just wouldn’t do it.” (I’ll note that Michael Scott had a copy of Trump’s book Think Like a Billionaire: Everything You Need to Know About Success, Real Estate, and Life on his bookshelf for several seasons of The Office.)

I pointed out it had been a while since Carell had made an out-and-out, big-laugh comedy. “I think it’s been about six years,” he said, counting back to early 2013, when he shot Anchorman 2: The Legend Continues (and not including a couple Despicable Me movies). This wasn’t a deliberate career choice, just that “the stuff that was interesting to me tended to be more dramatic.” He’d like to do a broad comedy again, he said, and was developing some projects along those lines.

But the rules of comedy have changed quite a bit in the last half decade, even in the last year. Jokes and characters that once seemed harmless might now generate social-media outrage, if not boycotts and involuntary sabbaticals. Carell’s thoughts returned to Michael Scott. “Because The Office is on Netflix and replaying, a lot more people have seen it recently,” he said. “And I think because of that there’s been a resurgence in interest in the show, and talk about bringing it back. But apart from the fact that I just don’t think that’s a good idea, it might be impossible to do that show today and have people accept it the way it was accepted ten years ago. The climate’s different. I mean, the whole idea of that character, Michael Scott, so much of it was predicated on inappropriate behavior. I mean, he’s certainly not a model boss. A lot of what is depicted on that show is completely wrong-minded. That’s the point, you know? But I just don’t know how that would fly now. There’s a very high awareness of offensive things today—which is good, for sure. But at the same time, when you take a character like that too literally, it doesn’t really work.”

At this point, Carell and I had been talking for more than two and a half hours. The restaurant had settled into a midafternoon lull. I was flagging, too. (I had a bad summer cold, and thanks to overdoses of Claritin and Mucinex, I kept hallucinating that Carell’s face had turned into Al Pacino’s from that movie where Pacino played the devil opposite Keanu Reeves.) But Carell was happy to keep going. He was concerned he hadn’t been interesting enough—not true, and again telling—and the conversation turned to actors he admires. Besides the aforementioned Peter Sellers, he named Tina Fey and Julia Louis-Dreyfus. Of the latter, he said, “She’s royalty. She’s another one who can play a comedic character, who can go super-broad in any direction but you always believe it. That center of humanity is always there.”

And that’s where we ended things, a little more college talk and a few parting pleasantries aside—with Carell turning a spotlight on someone else, fittingly enough.