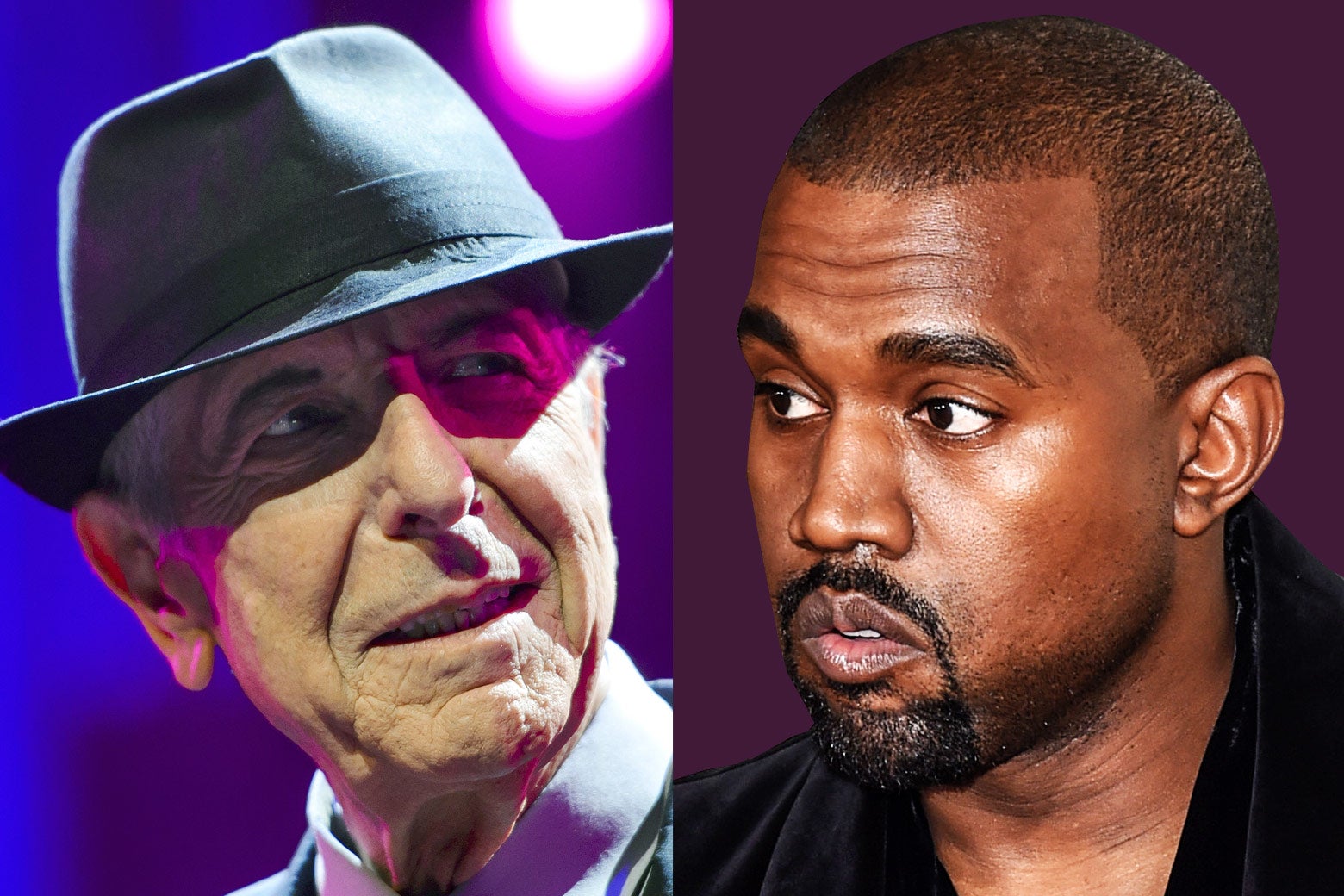

If I’d been asked to guess what Leonard Cohen would do from beyond the grave, I wouldn’t have been clever enough to say “rap battles.” But a diss track, as many are calling it, has turned out to be Cohen’s first hit since his death in November 2016. A poem called “Kanye West Is Not Picasso,” from Cohen’s new posthumous collection, The Flame, went viral on Thursday, the same day that the MAGA-hat-rocking, Trump-supporting rapper made a high-profile visit to the White House. Most reactions seem to have assumed that Cohen’s poem was a dismissal, expressing the same impatience with West’s overweening self-praise that the bulk of us are feeling—perhaps with a side dish of “Old Man Shakes Fist at Hip-Hop.”

But that’s getting the poem exactly wrong. It’s not an insult to Kanye West (nor to Jay-Z, who’s also mentioned). It’s a tribute.

Cohen isn’t around to confirm this, but remember that the poem is dated March 2015, when West’s right turn off the rails was still in the distant future. Clearly, it was inspired by several occasions when West compared himself with Picasso, including earlier that month in a speech at Oxford University. But its language is closer to the “rants” of the Yeezus tour, during which Ye (the name he now prefers) regularly issued such direct declarations as “I am Henry Ford. I am Michelangelo. I am Picasso.” Thus Cohen’s poem begins, “Kanye West is not Picasso/ I am Picasso.”

He continues, “Kanye West is not Edison/ I am Edison/ I am Tesla”—bringing up two other self-comparisons West made during that same period. (For someone who supposedly had no use for West, Cohen certainly seemed to keep up on his Ye news.) And then comes perhaps my favorite couplet in the whole poem, a response to Jay-Z calling himself “the Bob Dylan of rap music” in the 2013 track “Open Letter”: “Jay-Z is not the Dylan of anything/ I am the Dylan of anything.” (By Cohen’s own account, Dylan once told him, “As far as I’m concerned, Leonard, you’re No. 1. I’m No. 0,” meaning, “that his work was beyond measure and my work was pretty good.” In other words, Cohen knew artist rivalries.)

Obviously, these are jokes. But a particular kind: They’re rap boasts, albeit in Cohen’s own inimitable style. It seems plain to me that Cohen was amused by Ye’s over-the-top braggadocio and impressed by his rhetorical style, wanting to get in on the fun. If only I’d been born half a century later, he might have thought, I could have murdered it in a rap cipher. He’s freestyling, trying to top West’s ego with his own, to the point of absurdity: “I am the Kanye West of Kanye West … I am the Kanye West Kanye West thinks he is/ When he shoves your ass off the stage.” (Shout out to Taylor Swift.)

Consider two vital facts: One is that Cohen admired hip-hop from early on—logically enough, considering how close rap lies to poetry. In a 1993 interview with Seconds magazine, Cohen said, “For the same reasons I like country music, I like rap music. There’s a coherence in the lyric, and a position that is clear, and a language that is, by its nature and by the urgency of the requirements, a very clear language.” And in October 2001, he said to Flaunt magazine, “In the case of Eminem and some of the other rappers, the lyrics are impressive. I think it’s great. I studied and was formed in this tradition that honored the ancient idea of music being declaimed or chanted … to a rhythmic background. … If it is in bad taste, you know, much of what we cherish today was once considered in bad taste.”

You might even detect some rap influence in the stylistic shift that Cohen made around the time of 1988’s I’m Your Man album, with its deliberately cheap-sounding drum machines and a vocal style more marked by gruff recitation, especially in the more tongue-in-cheek songs like “Jazz Police.” (“Let me be somebody I admire/ Let me be that muscle down the street/ Stick another turtle on the fire/ Guys like me are mad for turtle meat.”)

What’s more, hip-hop sometimes returned the admiration by sampling Cohen in songs by T.I. and the Wu-Tang Clan, among others.

Even more crucially, the voice of a megalomaniac à la Kanye was one of Cohen’s own favorite lyrical personae. Consider a song like I’m Your Man’s “First We Take Manhattan”: “I’m guided by a signal in the heavens/ I’m guided by this birthmark on my skin/ I’m guided by the beauty of our weapons/ First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin.” Or “Field Commander Cohen” from 1974’s New Skin for the Old Ceremony: “Field Commander Cohen, he was our most important spy/ Wounded in the line of duty/ Parachuting acid into diplomatic cocktail parties/ Urging Fidel Castro to abandon fields and castles.”

Or even reach all the way back to a poem from his 1961 second collection, The Spice-Box of Earth, called “The Cuckold’s Song”: “The important thing was to cuckold Leonard Cohen/ I like that line because it’s got my name in it.” Substitute Kanye West’s name there, and the remark feels like it could have come from West’s last album.

The spirit of Cohen’s Kanye poem seems precisely to me like he recognized a kindred spirit on that level, another artist adept in the Zen of ridiculous self-aggrandizement, a spiritual discipline of inflating the ego to the point that it bursts. He felt moved, with no greater desire than to create a comic bagatelle, to see if he could out-Kanye Kanye, just as the poem declares.

It being Cohen, of course, he couldn’t resist reaching for the bigger picture in spots, as when he calls himself “The Kanye West/ Of the great bogus shift of bullshit culture/ From one boutique to another.” You could take that as a slam against rap or perhaps against Ye’s designs on fashion (though Cohen himself was a very fashionable guy). But it sounds to me more like a recognition that Cohen’s own 1960s heyday of hipster culture has been replaced by another, and that they all come with their own loads of bullshit. In the end, he reiterates, “I am the real Kanye West” and then quotes Duke Ellington, “I don’t get around much anymore”—another nod to that generational shift, meaning Cohen can’t really be a player in the rap game except on a make-believe level.

And then, in a classic Cohen gesture toward Revelation-style apocalyptic portents, he concludes, “I never have/ I only come alive after a war/ And we have not had it yet.” Those overtones were a constant in Cohen’s work, especially as he got older and became (even) more death-haunted and mystical about the world’s fate. He might not have been so lightheartedly engaged by Kanye if he’d known where the rapper’s sympathies were headed.

However, Cohen’s own politics were always complicated by his messianic inclinations, his push-pull relationship with Israel (he volunteered for the Israeli army during the Yom Kippur War, but later expressed empathy with the Palestinians as well) and his general preference to maintain a cosmic-scale perspective on worldly affairs. In the song “Democracy” from 1992’s The Future—an album that threw many listeners off by expressing anti-abortion sentiments in passing—he sings, “I’m neither left or right/ I’m just staying home tonight.”* Still, the coming errancy of his rap-battle partner Kanye is just another reason to feel some gratitude on behalf of “the grocer of despair” that he didn’t have to endure the many darknesses of the Trump era. One wonders if he might have felt we were finally having that war he perpetually saw on the horizon.

Correction, Oct. 13, 2018: This article originally misstated that the song “Democracy” seemed to express anti-abortion sentiments. It was another track on the album.