Tracing Ska Music’s Great Migration

A journey from Jamaica to California, via England.

“Skankin’ to the beat is an alright feelin’ / Skankin’ to the beat got my toe jams peelin’ / Skankin’ to the beat got the rude girls squeelin’ / I’m just skankin’ to the beat!” So goes the refrain of “Skankin’ to the Beat,” the 1985* hit song by Fishbone, a California ska band with a sizeable cult following. This song (and the “skankin’” dance style) would’ve been familiar to members of ska’s subculture in Los Angeles and Orange County in the 1990s, but the story of ska goes back much further.

“There’s a street in Jamaica, you all should know,” says Prince Buster in a YouTube video, introducing his 1967 ode to the birthplace of ska music, “Shaking Up Orange Street.” “The Prince,” born Cecil Bustamente Campbell on the song’s namesake street in Kingston, Jamaica, is widely regarded as the father of ska music. Orange Street was known as Jamaica’s premier musical avenue; it was once a hub for recording studios and various record stores, Prince Buster’s Record Shack among them. The concentration of music and members of the Kingston community on Orange Street created a culture of local fun, and it is ultimately that feeling of shared celebration and struggle that made ska music accessible worldwide.

Nina Cole, a scholar of Jamaican popular music, emphasizes the importance local DJs and their parties had in the genre’s development. “The rise of sound systems led to the creation of ska,” she says. Sound systems, which refer to both the musical equipment and the street parties they encouraged, were pillars of Jamaican musical culture, and are associated most closely with the rise of ska on Orange Street in particular. A group of mobile disc jockeys who traveled with towering subwoofers, turntables, and amplifiers, sound system operators were highly visible members of the Kingston neighborhood. They provided the streets with music, at first, as a way to make money by charging modest admission and selling food and alcohol.

Fostering an active dance scene was a priority, so the operators of these portable music stations struck up relationships with U.S. music executives in order to get the best American rhythm and blues records, particularly before another sound system operator could. This created friendly competition between Kingston’s several sound systems, who threw distinct yet somewhat similarly run street parties; who all shared the common goal of satisfying the masses through sound. Selectors, the men in charge of curating and selecting the music played, were very much aware of the impact their taste had on the Jamaican people.

Toward the end of the 1950s, “there was quite a bit of rural to urban migration … and as more people transitioned to the city there were some shifts [away from mento and calypso music, the more folk styles in Jamaica],” says Cole. Local musicians married the African rhythms of Caribbean mento, a genre all Jamaicans would have been familiar with, with the popular beats of R&B and jazz music: sounds more closely linked to the black American experience. Though sound systems were getting these American records shipped to the island, they were generally limited and severely delayed (sometimes arriving up to three years after they had peaked in the States). The working-class people of Kingston could not afford radios, which effectively cut off their access to non-local music, and the prices American record manufacturers demanded from DJs to import R&B records to Kingston grew increasingly steep. Sound system operators like Clement “Coxsone” Dodd and Duke Reid recognized this gulf, and filled it by using nearby music studios to record a new sound that blended elements from both local and imported music to create ska—an undeniably new sound with familiar enough influences to make it an instant success.

Ska music, a genre commonly known as “the music of the people,” was formally birthed in 1959, and is a hybrid sound that owes much of its success to the popularity of its influences. On the weekends, native Kingstonians would gather on “lawns” (open neighborhood spaces) to dance at the parties sound systems created. As a result, ska music was quickly associated with the joie de vivre of the working-class downtown locals who championed it.

Heather Augustyn, a journalist and author of five books on ska, notes that shop owners on Orange Street capitalized on the rise in foot traffic these public parties created, by using sound systems to entice party-goers into their shops, thus bolstering the economy in working-class Kingston. Speakers positioned high in trees peppered the scene on Orange Street, with the idea being “that if you heard the music a mile away, you would come over, pay to get in, and get curry goat and a Red Stripe.” Locals were able to participate in dance culture and be exposed to new musical styles, with the familiar beat of their neighborhood guiding them all the while. Once walked on as a Mom ‘n’ Pop shop thoroughfare, Orange Street was becoming ska’s de facto boulevard.

Though the ska genre started as a localized sound, its lyrical content is what gave it the wingspan to reach places beyond Jamaica. The “lyrics gave social commentary,” says Cole. “Things like unemployment, lack of social services. [Themes] which I think in [ska’s] later travels people grasped onto like, ‘Wait, this is happening where I live, too.’” Granted, most people tend to associate ska with upbeat, animated melodies, but the heaviness of reality found in many of the lyrics offered a somber contrast to the sweetness of the sound. Perhaps unsurprisingly, during ska’s ascent, it was met with “outright rejection” from the middle and upper classes, says Cole, “because there was this association with Black Jamaicans and African aesthetics and ideals.” While the island’s motto is famously “Out of Many One People,” there was “this homogenized civility, European ideals, and very stratified race and class prejudice that persisted,” which explains ska’s lack of radio airplay early on.

Ska was difficult to access outside of the yard-based sound system culture—“you really had to go to these places to hear it,” says Cole. Because of the close proximity between these Kingston-based parties, sound systems and their operators were fiercely competitive, and the battles between who could attract the most people with the newest music came to be known as “sound clashes.” These rivalries raised the stakes surrounding ska, which resulted in towering 12-foot-tall speaker stacks, and informal rankings of who played the most danceable music within earshot. Prince Buster’s fame was born from his reputation as a frequent sound clash winner, a local title that grew to have international clout.

In 1948, the United Kingdom opened its doors to citizens of British territories, because it needed a larger labor force to help rebuild its economy after World War II. As a result, West Indian immigrants traveled in great numbers to London, specifically neighborhoods like Brixton and Peckham. By the time ska was born on Orange Street these families were firmly settled in their new place across the pond, so, when the time came, ska music found a home in London, too. Around the early 1960s, the first British-Jamaican sound system was up and running, and British youths started to become exposed to ska music through their proximity to these Jamaican enclaves, which were working-class areas similar to Kingston back home. “They gathered together at house parties because that was their culture, and they missed home,” Augustyn says of the immigrant community.

It wasn’t long before their English neighbors developed a taste for the sound and ethos of ska music, played from the classic Jamaican vinyls booming through the sound systems, and with the growing presence of bands like The Specials, The Selecter, and Bad Manners, ska’s second wave, Two-Tone, was born. “[The British] loved [ska], and then they blended it with what they knew, which was early punk rock,” says Augustyn. This European twist on ska didn’t forget its roots. In fact, Two-Tone bands were known for being diverse, as most usually had one or more Jamaican members. A popular band of this era, Madness, got its name from a Prince Buster song of the same title.

Though ska had been played locally in Jamaica and England for years, it wasn’t until 1962 that it started to pick up global steam. On August 6 of that year, Jamaica won its independence. Augustyn, the ska scholar (skalor?), notes: “They were looking for a way to market Jamaica, literally. So the Jamaican tourist board and the Ministry of Culture and Welfare got together and decided to help [popularize] ska.” Convincing Jamaicans to fall in love with ska was not the battle; national pride as a newly “free” island was now understandably at the forefront, so homegrown Jamaican things like ska were embraced wholeheartedly. Ska music was simply part of the Jamaican identity, not unlike the green, yellow, and black of the flag.

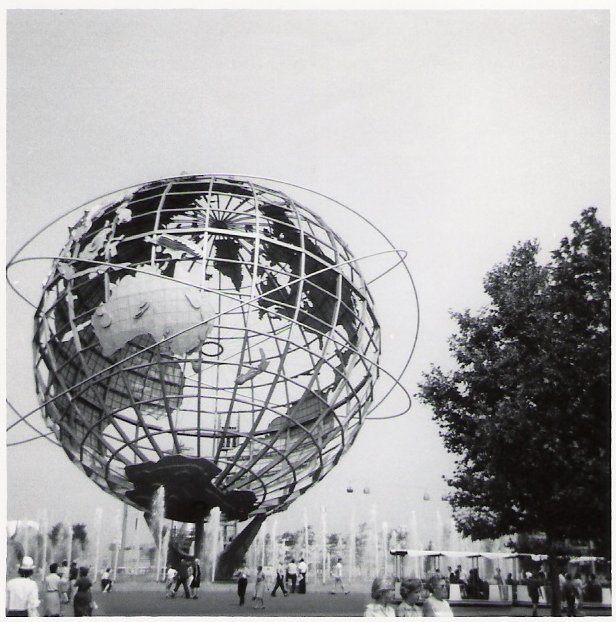

In 1964, the Jamaican government focused its attention on promoting ska to U.S. audiences and flew several ska musicians to perform at the World’s Fair held that year in New York City. Ska performances and dance classes were held to pimp the sound to new ears, but the genre didn’t quite stick on the east coast—perhaps, in part, due to a lack of authenticity. In Augustyn’s book, Ska: The Rhythm of Liberation, she explains how the version of ska brought to American audiences wasn’t totally true to the ska of Jamaica: “Not only were the downtown musicians blatantly overlooked in representing Jamaica at the fair, but the World’s Fair events at which ska was unveiled were far from the sound system yards. Instead, these events were sophisticated, stylish, and socially exclusive.” The strategy of “targeting the proper upper-class crowds, the ones who had money and could afford to travel to Jamaica to hear the island’s music,” was in opposition to the communities that ska was designed to uplift.

In the 1970s, reggae-devoted radio shows promoting Jamaican artists started to make their way to Southern California airwaves, and record stores owned by British and Jamaican expatriates stocked Caribbean music loyally. Early Two-Tone bands in the coastal state started getting booked at clubs, and ska soon became a noticeable mix of reggae and angsty punk, with a dash of California’s breezy frivolity. In keeping with the history of sound systems, whose operators verbally advertised the music as it played, the hosts of these clubs not only introduced the ska songs, but narrated the night as a way to keep the crowd involved. As time went on, radio DJs played a similar role, when ska took flight from its beginnings as a terrestrial sound and expanded to the airwaves.

Jimmy Alvarez is a radio DJ located in Southern California, and for nearly 25 years has brought music to stations like KROQ and TNN Radio. As someone who was responsible for exposing Orange County audiences to ska music during its third wave in the late 1980s and 1990s, Alvarez believes its later-stage popularity in America had less to do with the music itself and more to do with the ideology behind it.

“The thing about ska is that it has one common theme: unity and family,” he says. “Yes, the music was good, but that was only part of the glue. The unity among races, and teens that had issues with the status quo, is what bound them.” I ask Alvarez about the meteoric rise of ska-influenced Orange County bands like Sublime and No Doubt during this era. “The OC,” as it is affectionately known, is decidedly not a West Indian immigrant community, and I’m curious about how a place with such a vastly different demographic than Jamaica birthed bands that did justice to the ska genre. “The OC community is true to its origins,” says Alvarez. “If you’re good, the locals will let you know. If you’re not, or if you’re disingenuous in any way, the locals will let you know. And you have to pay homage to the genre’s roots to get to the next level. Most of the successful bands that came out of OC didn’t forget their history, and often credited their predecessors with acknowledgment or covers.” Again, ska found its way to a community heavy on the promotion and advancement of local acts.

Brian Mashburn, a musician and former member of the bands Save Ferris and Starpool, remembers the energy ska’s sound brought to Orange County fondly, and how what was once a subculture snowballed into a real scene. “Ska was cool because it was for people who kinda had all the energy to go to a punk rock show but didn’t necessarily want to beat the crap out of each other,” he says. ”It really appealed to people who couldn’t go to bars yet, so I think it was a youth thing as well.” Mashburn emphasizes the organic growth of ska in California, noting that he and his bandmates were just “trying to be a part of our local scene.” At the time, there weren’t many venues to play music in Orange County, so local promoters found random spots to throw shows, operating similarly to Orange Street’s sound system operators. As the bridge between the people and the music, promoters (and operators) were able to pin the ska sound to familiar, convenient public spaces. Mashburn reflects on one of Save Ferris’ early shows in the ‘90s, and a moment that cemented his love for the genre. “We started playing and there were like 50 people in this tiny little dance studio, and everybody’s dancing, everybody’s having a great time. I looked up and thought, ‘This is the best thing ever.’”

While ska music, the forefather to reggae and rocksteady, has always been intertwined with Jamaican identity, it has also been able to find local footing in places that became aware of it decades after it first exploded from sound systems on Orange Street. The current ska revival, which some affectionately refer to as its fourth wave, is picking up speed, says Cole, because ska’s pioneers “have passed away in recent years, so there’s this realization that this is the last chance that [bands] get to hear or learn from the people who were creating this music.”

Mashburn’s continued interest in the sound, even though he’s now transitioned into different styles of music, is a testament to how ska was able to nestle itself in the hearts of its audiences no matter where it was: “I’ve played in a lot of different groups now over the years and done a lot of different styles, but one of the reasons why I still keep a foot in the ska world is because those shows are a lot of fun,” he says. “You see people dancing and really going at it, and that feeds back to the band and then we start going crazy on stage, and that feeds back to the audience, which creates this really cool, positive feedback loop. I honestly haven’t really felt that with any other scene or any other type of style I’ve played.”

*Correction: We originally said “Skankin’ to the Beat” was released in 1989. It was released as a single in 1989, but first came out as a B-side in 1985.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook