The Risky Business of Branding Black Pain

The commodification of civil-rights activism may appear revolutionary, but it can undermine the basic tenets of social movements. Colin Kaepernick's Nike campaign illustrates this conundrum perfectly.

“It is both humiliating and humbling to discover that a single generation after the events that constructed me as a public personality, I am remembered as a hairdo.”

These are words from the Black Power icon and lifelong activist Angela Davis’s 1994 essay, “Afro Images: Politics, Fashion, and Nostalgia.” In the years following her emergence as a Communist, a revolutionary for black freedom, an enemy of the state, and an enduring voice of prison abolition, Davis’s image—one that is considered by many to be synonymous with black liberation and the social-resistance movements of the 1960s and ’70s—has been slapped onto endless memorabilia, such as apparel and collectibles, in which the entirety of her scholarship, activism, and the larger political effort she represents are mostly reduced to a logolike image of her Afro. Davis was greatly disturbed by how her likeness was used as a backdrop for advertising, and by how little control she had over her own image. In her writings, she laments that she was reinterpreted as a “fashion influencer,” and the ways this undermined her message, her activism, and her anti-capitalist principles. Davis is, for many, a living legend, but for others she is the blueprint for how to merchandise a movement.

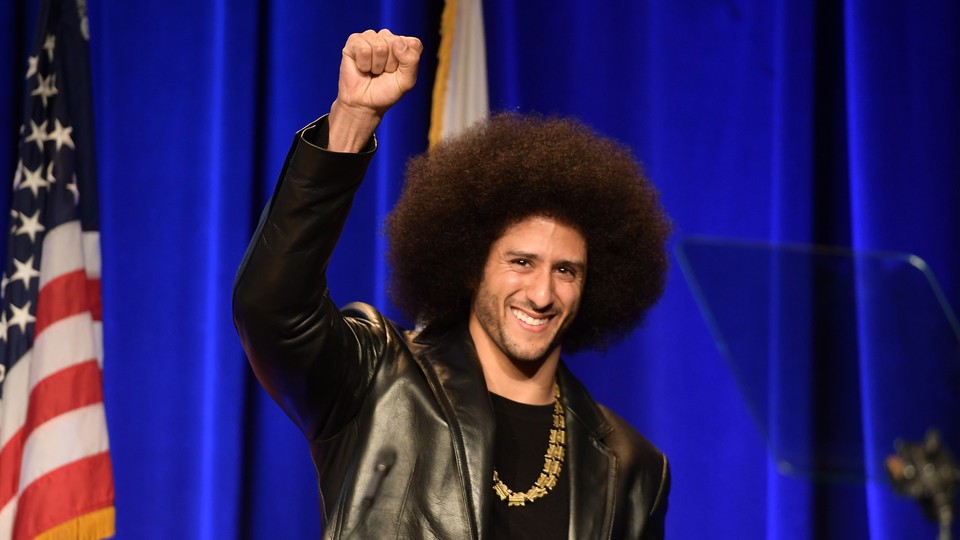

Last week, the release of Nike’s 30th-anniversary “Just Do It” ad campaign featured a tightly cropped still of Colin Kaepernick’s face and Afro, beckoning us to “believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything.” If Nike’s imagery of Kaepernick in a black turtleneck and Afro conjures a dorm-room poster of yore, that is quite intentional. In his latest role as an outspoken celebrity voice against police brutality, Kaepernick has been routinely photographed wearing his hair in the style that signals the Black Power movement of which Davis and other revolutionaries were a part. The commercialization of social-justice activism has long required the market-ready iconography of its most visible individuals. Nike’s images are meant to recall Davis—not as a person, but as a moment—and the resistance as fashion that came out of her image. In teaming up with Nike, Kaepernick voluntarily lends his image—and any contemporary vestiges of Black Power writ large—to corporate commodification.

The branding that requires this type of iconography is, of course, highly profitable. Research-marketing teams and advertisers spend entire careers trying to successfully manufacture the authenticity that draws consumers to a product, voters to a politician, or demographics to a brand. But manufactured movements are easily detectable as fraudulent. The real game is usurping an organic, organized resistance, and by ingesting the images of black protest while pruning off any of its actual political goals, the Kaepernick campaign has already led to Nike’s online sales ballooning 31 percent since its launch.

The background of Kaepernick’s image against the foreground of Nike’s copy, slogan, and logo are meant to compel audiences to believe that individual determination, in the context of social resistance, can overcome all odds, and that membership in this movement can be procured with the purchase of Nike shoes and apparel. This narrative of independent perseverance as a solution for toppling odds stacked against those who are disenfranchised not only fails to achieve the reform for which Kaepernick is pushing, it also undermines it.

For one, consumers are to believe that this Nike nation is helmed by a business that can act as human beings have throughout history to change injustices. Nike’s brand identity angles toward rebellion, but there is no actuality to that in its corporate structure, which comprises the same basic anatomy of its Fortune 500 peers. Publicly traded entities, as many seem to have forgotten in their rush to applaud Nike, have a fiduciary responsibility to their shareholders and cannot by law perform the selfless sacrifices that are capitalized upon in this campaign.

Secondly, the reductive commodification of Kaepernick’s political track record to an ad spot about personal will sabotages his message of withholding his national allegiance in the face of glaring racial disparities. Through his already established, authentic image that embodies pro-black politics and aspirational masculinity, viewers are invited into a myth that the end of structural racism can be brought about by essentially the same perseverance required to master a kick flip on a skateboard. In this seductive appeal to a doggedly American sense of individuality, social change is only a matter of marginalized people sticking it out. Those who benefit collectively from the subjugation of others are not required to give up anything, least of all their fly new sneakers.

To be clear, one may look at all of this and argue that by teaming up with Nike, Kaepernick is making the smart move of controlling the narrative of his own image, which, if Davis is any lesson, will be commodified anyway. But Kaepernick has no control over the way his image is received by Nike consumers. In this instance, he is a proxy—a window-dressing model for the larger project of packaging Black Power images, which is jarringly similar to the cultural reimagining that deemed Davis’s style and the black leather jackets and berets of her contemporaries irresistibly and undeniably cool. In offering himself as a campaign spokesperson, Kaepernick is validating (and, thus, making more profitable) a form of social-justice capitalism that compromises a large-scale political protest’s longevity and efficacy. It’s important to consider the high costs of assisting a corporation in peddling a social struggle, as Davis forewarned that historical revolutions could be reduced to trends. When so goes the fashion, there goes the movement.