The Lie of Little Women

Peering into the secrets of Louisa May Alcott’s real life sheds light on her treasured coming-of-age tale.

Early in the recent BBC/PBS miniseries Little Women, the first significant adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s novel in 24 years, Laurie (played by Jonah Hauer-King) tells Jo (Maya Hawke)—the first March sister he falls in love with—how much he enjoys watching her family from his nearby window. “It always looks so idyllic, when I look down and see you through the parlor window in the evenings,” he says. “It’s like the window is a frame and you’re all part of a perfect picture.”

“You must cherish your illusions if they make you happy,” Jo replies.

The scene nods to an awkward truth: Little Women is the window tableau and we, its readers, are Laurie, peering in and savoring its sham perfection, or at any rate its virtuous uplift. During the 150 years since the novel’s publication, fans have worshipped Alcott’s story of the four March sisters and their indomitable mother, Marmee, who navigate genteel poverty with valiant acceptance and who strive—always—to be better. Detractors (notably fewer in number) have generally fastened on some version of that saga of gritty goodness too, irritated rather than awed.

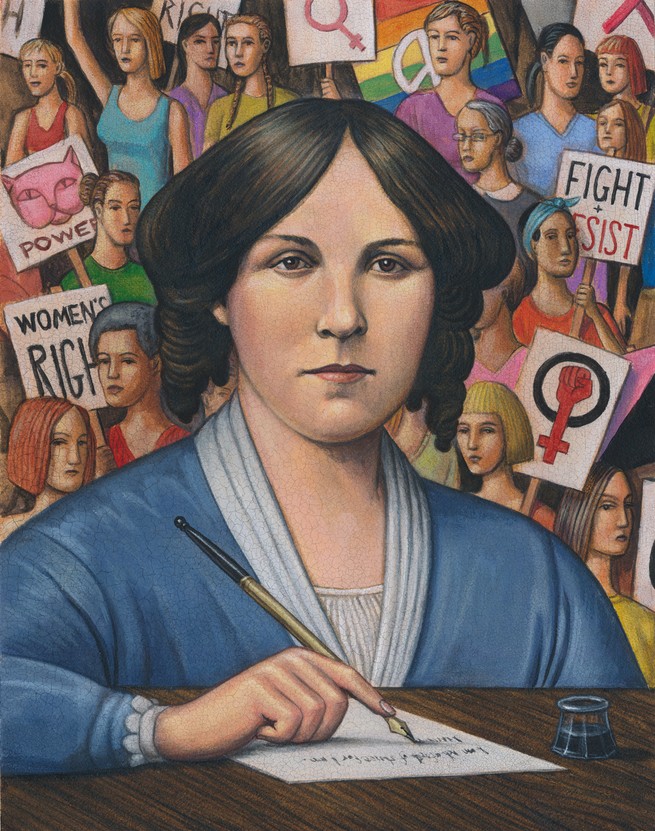

But Alcott herself took a more skeptical view of her enterprise. She was reluctant to try her hand at a book for girls, a kind of writing she described later in life as “moral pap for the young.” Working on it meant exploring the minds and desires of youthful females, a dismal prospect. (“Never liked girls or knew many,” she wrote in her diary, “except my sisters.”) While writing Little Women, Alcott gave the fictional Marches the same nickname she used for her own tribe: “the Pathetic Family.” By the final chapter of Jo’s Boys, the second of two novels that followed Little Women, Alcott didn’t try to hide her fatigue with her characters, and with her readers’ insatiable curiosity about them. In a blunt authorial intrusion, she declared that she was tempted to conclude with an earthquake that would engulf Jo’s school “and its environs so deeply in the bowels of the earth that no [archaeologist] could ever find a vestige of it.”

The lie of Little Women is a multifaceted one. The book, a treasured American classic and peerless coming-of-age story for girls, is loosely inspired by Alcott’s own biography. Like Jo, she was the second of four sisters who grew up in Massachusetts under the watchful eye of an intelligent and forceful mother. Unlike Jo’s early years—in which her father is absent because, after losing the family fortune, he is serving as a chaplain in the Civil War—Alcott’s childhood was blighted by the failure of her religious-fanatic father, Bronson Alcott, to provide for his family. Stark deprivation, rather than the patchy poverty of the book, was a daily reality.

The four sisters, frequently cared for by friends and relatives, were itinerant and often obliged to live apart. Alcott’s sister Lizzie contracted scarlet fever while visiting a poor immigrant family nearby, much as Beth does in the novel. But Lizzie’s death at 22, unlike Beth’s around the same age, followed a protracted, painful decline that some modern biographers attribute to anxiety or anorexia. And while Jo was mandated by convention (and Alcott’s publisher) to pick marriage and children over artistic greatness, Alcott chose the opposite, relishing her newfound wealth and her success as a “literary spinster.”

For the first 80 or so years after Little Women was published, conflict scarcely arose over how to interpret it. Readers adored the book and its two sequels without probing for Alcott’s own feelings about them (curious though her fans were about her life). Not until 1950 did a comprehensive biography appear: Madeleine B. Stern dug into her subject’s fraught family history, and outed the grande dame of girls’ lit as the author (under a pen name) of sensationalist stories about murder and opium addiction. Then, from the 1970s onward, feminist critics began examining Little Women from a new perspective, alert to the inherent discord between text and subtext. As the literary scholar Judith Fetterley argued in her 1979 essay “ ‘Little Women’: Alcott’s Civil War,” the novel is about navigating adolescence to become a graceful little woman, but the story itself pushes back against that frame. The character who continually resists conforming to traditional expectations of demure femininity and domesticity (Jo) is the true heroine, and the character who unfailingly acquiesces (Beth) dies shortly after reaching adulthood.

The blossoming of feminist criticism finally gave Little Women the thoughtful, rigorous analysis it deserved. Exploring the internal tug-of-war between the novel’s progressive instincts and the era’s prevailing constraints revealed a book that was far from pap. And yet Little Women continues to be sidelined in the American canon. Its reputation as fictional fare for and about girls and women prevents it, even now, from achieving the status of, say, Huckleberry Finn. Many male readers feel, as G. K. Chesterton put it, like “an intruder in that club of girls.” At the same time, the domestic setting and sermonizing that irked Alcott herself can strike contemporary female readers as bland and restrictive: The book’s popularity shows signs of waning among a younger audience. But the fascination with Little Women endures among writers and filmmakers, as a current surge of adaptations attests. Inspired by the challenge of bridging the gap between Alcott’s life and Alcott’s writing, efforts to renew and expand its power help illuminate complexities in a novel whose literary stature is ripe for reevaluation.

The wealth of adaptations of Little Women over the past century is proof of its durability, and also its malleability. As Anne Boyd Rioux writes in Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why It Still Matters, stage and screen versions of the novel have reflected the eras they were made in. Early ones offered morally and socially wholesome entertainment in the presumed spirit of the original text. During the Great Depression, when audiences were consoled by the idea of simpler times, theatrical performances of Little Women were popular across America. By 1949, when Mervyn LeRoy directed the fourth film adaptation, this one with an all-star cast (Janet Leigh as Meg, June Allyson as Jo, Margaret O’Brien as Beth, and Elizabeth Taylor as Amy), consumerism had become a patriotic duty. So the movie’s writers invented a new scene in which the March sisters go on a Christmas spending spree with money from Aunt March.

Rioux’s astute examination of the long life of Little Women in American culture is itself, fittingly enough, very much of its era: She draws particular attention to the problematic paternal shadow looming over Alcott’s enterprise. Rioux, a professor at the University of New Orleans, delves into Alcott’s background, emphasizing that the young Transcendentalist—who grew up in a circle that included Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau—saw writing as a more practical and less lofty endeavor than her male peers did. As for Bronson Alcott, “the only occupations that did not compromise his principles were teaching and chopping wood,” Rioux writes of the radical education reformer, whom she characterizes as flaky at best and unstable at worst. His family, forbidden to eat animal products or wear anything but linen, often starved and froze in New England’s fierce winters. (At Fruitlands, a utopian community he co-founded in the 1840s, root vegetables were initially outlawed because they grew in the direction of hell.)

For Alcott, who shared her father’s creativity but lacked his zealotry, writing was both a path to realizing her literary ambitions and a means of feeding her family. After publishing a couple of stories in The Atlantic, she met with a colder reception from the magazine’s new editor, James T. Fields, who in 1862 gave her $40 to open a school instead—which she did, although it soon failed. She returned to writing sensational stories, which she described as “blood and thunder tales,” published in weeklies, some under the pseudonym A. M. Barnard, and featuring passionate, assertive female characters who scheme and adventure their way to prosperity. While she didn’t want her father or Emerson to know she was stepping into the literary gutter, she seems to have enjoyed the “lurid style,” and thought it suited her “natural ambition.” The money she earned was also crucial. “I can’t afford to starve on praise, when sensation stories are written in half the time and keep the family cozy,” she wrote in her journal.

The irony was that Little Women, which Alcott embarked on with reluctance and wrote with formulaic conventions in mind, turned out to be the book that made her name and her fortune. It’s impossible not to wonder what she might have achieved had she been able to throw off the “chain armor of propriety,” the phrase she used to describe the burden of having “Mr. Emerson for an intellectual god all one’s life.” The recent BBC/PBS miniseries nods briefly to nonidyllic realities, but mostly doubles down on the domesticity front: Rustic chic pervades the March home, a twee extravaganza of muslin, bouquets of baby’s breath, and homemade jam. If each era gets the Little Women adaptation it deserves, this is Alcott as fall-wedding Pinterest board. But in 1994, Gillian Armstrong, directing the most successful film adaptation to date, took a bolder approach.

Robin Swicord, who wrote the screenplay, created virtually every line of dialogue from scratch, saying that she had imagined what Alcott might have written had she been “freed of the cultural restraints” of her time. The result swerves from the usual homey scene to offer a politically engaged drama in which Marmee (Susan Sarandon) and Jo (Winona Ryder) advocate for women’s suffrage and none of the Marches wears silk, because it’s produced using slavery and child labor. Males are relegated to the margins: The March household is a matriarchy, presided over by a fierce feminist and reformist crusader who emphasizes the importance of education and moral character rather than interior decoration. Swicord even names Marmee Abigail, which was Alcott’s mother’s name.

Focusing on the Marches as more than just daughters, sisters, and wives, Armstrong’s Little Women also foregrounds its characters’ creative talents—their plays, their newspaper, Jo’s writing, Amy’s art—without sacrificing the aspects that readers have come to love, not least the have-it-all denouement that Alcott fiercely, and by now famously, resisted delivering in its most treacly form: Chafing at the pressure to marry Jo off, she made sure to flout readers’ desperate desire to see Jo end up with Laurie. Alcott instead paired her with the older, far less glamorous Professor Bhaer—a subversive step beyond which a late-20th-century director and audience plainly weren’t ready to go, aware though Armstrong surely was that the author herself had yearned to leave Jo single.

In the future, though, who’s to say what choices new film incarnations might make? Lea Thompson is starring as Marmee in a feature-length “modern” update of Little Women pegged for release this year, and the actor and Oscar-nominated director Greta Gerwig is adapting and directing a version to appear in 2019; Robin Swicord is back, this time as a producer, and the star-studded cast will include Meryl Streep. However the latest adapters proceed, they have already found—as have directors and writers before them—that the reality of Alcott’s life adds a liberating, complicating dimension to the story of Little Women. For her, literary success came with suppressing her creative instincts. “What would my own good father think of me if I set folks to doing the things I have a longing to see my people do?” she confided to a friend about her fictional characters. At the same time, that literary success gave her a personal freedom she couldn’t afford to give her characters—at least not those in the March family. Writing as A. M. Barnard, she empowered her adult heroines in ways her little women could only dream of.

But dream they did. Jo’s creativity, her nonconformism, and especially her anger—that energy constantly undercuts the sanctimony Alcott dreaded in a genre that she, without blood and thunder, found ways to sabotage in Little Women. Her ambivalence emboldened her to unsettle conventions as she explored women’s place in the home and in the world—wrestling with the claims of realism and sentimentality, the appeal of tradition and reform, the pull of nostalgia and ambition. Her restless spirit is contagious. The more Alcott’s admirers seek to update her novel, drawing on her life as context, the more they expose what her classic actually contains.

This article appears in the September 2018 print edition with the headline “The Lie of Little Women.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.