The Writer Who Makes Perfect Sense of Classical Music

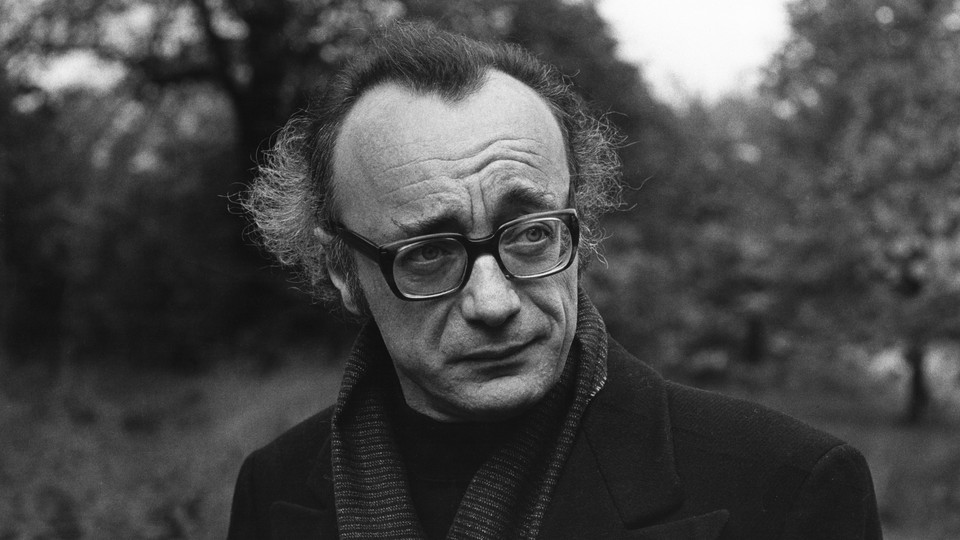

Alfred Brendel’s essays about Beethoven, Schubert, and many others are deeply relevant to performers and amateur listeners alike.

Alfred Brendel, one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, is also a great writer. You can often detect a good-natured smirk behind his words, but right there with it is a genuinely humane seriousness. His writing, always engaging, strikes a balance between solemn reflection and undeniable wit. A perfect example of this balance can be found in his 1985 essay “A Mozart Player Gives Himself Advice,” in which Brendel urges the reader to reject the idea of Mozart as sugar sweet and precious. He writes that “the cute Mozart, the perfumed Mozart, the permanently ecstatic Mozart, the ‘touch-me-not’ Mozart, the sentimentally bloated Mozart must all be avoided.” Brendel doesn’t dawdle in getting to the point, and when he does, the point is sharp.

Now retired from the concert stage, Brendel, 87, has written extensively throughout his life on his approach to interpretation and performance for publications such as The New York Review of Books and The Musical Times. He’s also published many books on music, most notably Musical Thoughts and Afterthoughts and Music Sounded Out. The essays and lectures of each of those books (plus several previously uncollected works) are gathered in Music, Sense, and Nonsense: Collected Essays and Lectures, now being released in paperback.

In these essays and lectures, Brendel considers sound, silence, sublimity, humor, and the performer’s critical role in the experience of music. What also makes this collection so relevant is just how appealing his analysis and commentary are to scholar, performer, and amateur listener alike—a rare accomplishment for anyone writing about classical music.

In “Form and Psychology in Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas,” a lecture that was originally published in Music and Musicians in 1971, he says that “although I find it necessary and refreshing to think about music, I am always conscious of the fact that feeling must remain the alpha and omega of a musician.” It’s the role of the performer, in other words, to both interpret the music and convince the audience of its immediacy and relevance.

The musician’s fidelity to the composer-performer-audience nexus is as important as it is difficult. A careful listener in a concert hall might notice that music is surrounded on all sides by quiet. “The musician wants to hear the silence,” Brendel notes:

She is there before and after the sound, tacitly breathing in the rests, at times, as in Schubert’s Sonata in B flat, the source of the beginning, elsewhere, as in Beethoven’s last three Sonatas, the designation to be reached: as the withdrawal into an inner world, the throwing off of all chains, the ultimate merging with silence.

Ever the performer, he wonders: “I hear myself. The public hears me. Do I hear the composer?”

The best attempt at an answer comes in Brendel’s writing about the multiply talented composer, pianist, and writer Ferruccio Busoni. In “A Peculiar Serenity,” Brendel writes about Busoni’s idea that musical interpretation “springs” from “sublime heights” and that, when it’s in danger of falling, Icarus-like, back to Earth, the performer must guide it back to those heights. Brendel, in kind, asserts that it’s the performer’s role to return “the creations of music” to “that elemental power beyond human concerns,” which is shared by composer and performer alike.

This all might seem a bit dramatic to the nonperformer until you consider what a performer is really trying to do onstage. It’s easy to take for granted that a performance should speak directly to a listener’s passions, vulnerabilities, and sense of self. What many listeners might not fully consider is that the experience is almost totally in the hands of the performer, someone tasked with somehow summoning the ethereal without losing the audience in the process.

But if there’s going to be so much talk of the sublime, there should be just as much talk about humor. Mozart comes to mind. His comic operas teem with a cleverness matched only by their humanity. On Mozart, Brendel quotes Busoni, who might have put it best: “In the most tragic situation, he is ready with a joke—in the most hilarious, he is capable of a learned frown.” In “Must Classical Music Be Entirely Serious?” Brendel considers humor in what, to many, might seem like the least funny music imaginable. So Mozart was funny, sure, but what about Beethoven and Haydn? Yes, them too. Sensing some musical mischief in and around Vienna, the Austrian Emperor Joseph II wagged his finger at what he saw as “Haydn jests.” And Brendel cites the German writer and musicologist Friedrich Rochlitz, who wrote that “once Beethoven is in the mood, rough, striking witticisms, odd notions, surprising and exciting juxtapositions and paradoxes occur to him in a steady flow.” Brendel builds off this observation to reflect on Beethoven’s humorous side.

Writing on the first movement of the composer’s Piano Sonata No. 16 in G Major, Op. 31 No. 1, Brendel notes:

there are further clues to [Beethoven’s] comic intentions: the two hands that seem unable to play together; the short staccato; the somewhat bizarre regularity of brief spells of sound interrupted by rests. The character that emerges is one of compulsive, but scatterbrained, determination. The piece seems unable to go anywhere except where it should not.

Brendel observes here that the clear musical irregularity—including a second theme starting in the mediant (3rd) B major instead of the more traditional dominant (5th) D major—would have sounded odd to a listener of that time (and this one, too). Brendel sees this as a joke of Beethoven’s on the late-18th and early-19th century classical-music tradition, which was defined largely by tonal balance, symmetrical phrasing, and rational thematic development.

What Brendel means, more broadly, is that if you feel like the music is winking and sticking its tongue out at you, you’re probably right. And you don’t always need to be deeply learned in form and harmony (though it might help) to appreciate these musical jokes. Sometimes what’s funny in classical music is just what sounds wrong; that’s why it’s funny. Still, Brendel laments how difficult it is to be humorous or lighthearted in the concert hall, the atmosphere of which is often preset to Immanuel Kant’s notion that the object of beautiful art “must always show a certain dignity in itself.” Brendel disagrees. “For my part,” he writes, “I am perfectly happy to enjoy the ‘sublime in reverse,’ and leave Kant’s dignity behind where Haydn and Beethoven took such obvious pleasure in doing so.”

In his writing, Brendel often refers to the idea of the German poet Novalis that “in a work of art, chaos must shimmer through the veil of order.” For a performer like Brendel, balancing chaos and order requires a capacity for both seriousness and playfulness, and a comfort with some overlap. He holds that a totally logical world would be very regrettable, that there needs to be a balance between the rational and the irrational, the finite and the infinite. The performer and the listener each can think of this productive tension as that between sound and silence. Loving music, Brendel suggests, means embracing its fleeting moments as well as the silence out of which they come.