The Next Populist Revolution Will Be Latino

Democrats are betting on a diversifying electorate to secure their party’s future, but second-generation Latinos won’t willingly accept a deeply unequal society.

Immerse yourself in the pro-immigration literature of Democratic Party thinkers, and you will notice a curious pattern of argument: High levels of immigration have awakened the racism and bigotry that have fueled the rise of right-wing populism, but it is nevertheless best to press forward with the policies that have ostensibly produced this fearsome reaction. Why? Because slowing the pace of immigration would be a callow surrender to bigotry. But also because, in the fullness of time, a unified coalition of college-educated white liberals, African Americans, and working-class immigrants and their descendants will vanquish the aging rump of reactionary whites.

The dream of a so-called rainbow coalition has been part of the liberal imagination since at least the presidency of Richard Nixon, when the left envisioned it, albeit prematurely, as a counterpoint to his “southern strategy.” The term itself was coined in 1968 by the activist Fred Hampton, who hoped to build a multiracial alliance devoted to revolutionary socialism, but it entered the mainstream in the 1980s, when Jesse Jackson endeavored to make racial justice a central tenet of the Democratic Party’s platform. Democrats have consistently been more supportive of social programs that benefit low-income people of color, including immigrants, than have their Republican rivals, which has helped cement their minority support.

In recent years, meanwhile, the white working-class share of the electorate has dwindled, in part because of rising education levels, low native birth rates, and an influx of working-class immigrants—trends documented by Ruy Teixeira, the political demographer and prophet of rainbow liberalism, in his new book, The Optimistic Leftist. The promise of the rainbow coalition thus seems ever closer to fruition. Among true believers, every liberal defeat, up to and including the 2016 presidential election, is best understood as little more than the dead-cat bounce of white resentment politics.

Confident pronouncements about the coming triumph of the liberal coalition tend to neglect an awkward question, however. Who will be in control of this bloc when it finally achieves its inevitable victory? Will it be college-educated white liberals, who play such an outsize role in shaping the left’s ideological consensus today, and who dominate the donor base and leadership of the Democratic Party? Or will it be working-class Latinos, whom white liberals are counting on to provide a decisive electoral punch?

In the age of Donald Trump, college-educated white liberals consider right-wing white populists in small towns and outer suburbs to be the gravest threat to their values and, sotto voce, their power and influence. Many seem to assume that rainbow liberalism will remain deferential to the demands of avowedly enlightened, well-off people like themselves—yielding a future in which student loans for graduate degrees are forgiven, property values in gentrified urban neighborhoods and fashionable inner suburbs are forever lofty, service-sector wages never quite rise to the point where hiring help becomes unaffordable, and, of course, rural white traditionalists are banished from the public square.

But what if working-class Latinos aren’t especially interested in serving as junior partners in a coalition led by their self-proclaimed white allies? What if they instead support new forms of anti-establishment politics, rooted in grievances and vulnerabilities that place them at odds with liberal white elites?

To see why members of the Latino second generation might turn against rainbow liberalism, note the essential role their parents play in today’s stratified American cities. The mostly white professional classes of the country’s prosperous coastal enclaves depend on immigrant laborers to be their helpmates; these laborers, in turn, depend on these employers for their livelihood. Most of these immigrants aren’t laying the groundwork for socialist revolution, for the obvious reason that they are more concerned with providing for their families. Relative to native-born workers, newcomers are more inclined to accept low-wage work and to live in insalubrious conditions.

This is especially true of low-skill immigrants, who greatly increase their income by moving to the United States, even when doing so places them among the poorest of America’s working poor. Rather than look at other Americans, they typically compare their lot with that of other impoverished immigrants, or with that of the loved ones they’ve left behind in their native country. To be an immigrant is to be the author of one’s own fate—and to accept diminished status, low pay, and even dangerous working conditions as the price of economic betterment.

The political influence of the working-class newcomers is muted. Few low-income immigrants become naturalized, in part because the cost can be prohibitive. In any case, naturalized citizens vote at lower rates than the native-born. As for unauthorized immigrants, they have even less political influence. If they were citizens, they would undoubtedly demand better wages and working conditions from their employers, and they’d have the political muscle to get their way at least some of the time. Instead, they are forced to toil in the shadows.

But the children of immigrants, born and raised on American soil as American citizens, will have a different experience. They’re more likely to compare their economic circumstances with other Americans’ than with those of the people their parents left behind. The comparison paints an unflattering picture. As the economists Brian Duncan and Stephen Trejo have observed, on average, first-generation Latino immigrants are burdened by a very low level of formal education. Seventy percent of Latino infants in the U.S. are born to mothers with a high-school education or less. Though this deficit grows smaller in the second generation, it remains strikingly large relative to native-born whites.

The immigrant’s rise from an impoverished upbringing to middle-class prosperity is one of the great glories of modern American history, and a comforting precedent. Some people insist that the children of today’s working-class Latino immigrants will fare just as well as those of the working-class European immigrants who settled in the U.S. during “the Great Wave” of immigration, which stretched from the 1880s to the restrictionist legislation of the 1920s. But there are many differences between that era and our own.

In mid-20th-century America, a flourishing manufacturing sector was desperate for low-skill labor, which provided many children of Great Wave immigrants with an opportunity for economic uplift. In recent decades, offshoring has given manufacturing employers an alternative to relying on domestic sources of low-skill labor. Service-sector employment has filled the breach, but many of these jobs are precarious and pay poorly. As I write this, at a time when the labor market is notably tight, wage growth for non-college-educated workers remains dismally slow.

American society has also grown more unequal; the social distance separating the children of working-class immigrants from those of well-off natives has become a chasm. On average, Latino immigrants are at least as well educated as the Great Wave immigrants from Europe were. The difference is that educational attainment among the U.S.-born has increased substantially. Closing this gap in a single generation will not be an easy feat. Among second-generation Latino adults, 47 percent have no more than a high-school diploma.

This painful reality will, I suspect, engender cynicism about whether U.S.-raised Latino youth can expect to live the American dream. That cynicism is already beginning to reveal itself. In December, Conor Williams, a progressive policy researcher and former schoolteacher, interviewed a group of high-achieving students of color at a Brooklyn charter school. All were from immigrant families. One of them, Esther Reyes, told Williams: “The American dream we see in movies or in shows or in books, it’s an American dream for white people.” She added: “I don’t think it exists.”

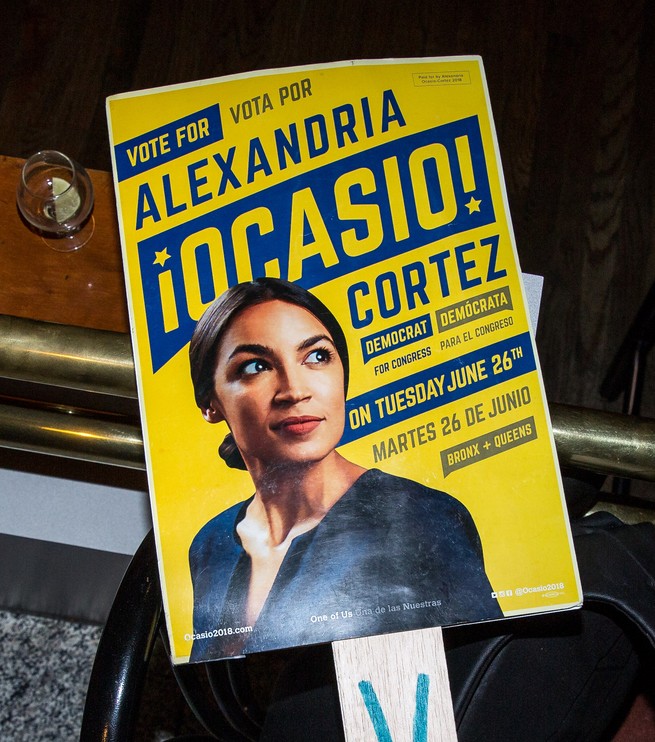

In June, we saw a glimpse of what this cynicism might augur politically. Representative Joseph Crowley of New York, the fourth-ranking Democrat in the House, was ousted in a primary by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a 28-year-old former organizer for Bernie Sanders and a member of the Democratic Socialists of America. “What I see is that the Democratic Party takes working-class communities for granted,” Ocasio-Cortez said a few days before voters went to the polls. “They take people of color for granted, and they just assume that we’re going to turn out no matter how bland or half-stepping [their] proposals are.” Despite having been vastly outspent by her long-tenured opponent, the Latina candidate won the majority-minority New York City district handily.

The logic of rainbow liberalism says that the anger of working-class Latinos and other marginalized minorities ought to be directed at hateful working-class whites in the heartland. But it’s not hard to imagine second-generation Americans choosing a different target for their ire: the white overclass of coastal America.

This class has heretofore been able to count on the support of immigrants, in part because of their commitment to helping that group gain access to the safety net that the Democratic Party has championed and fought to protect. But second-generation Americans may have less patience than their parents for a status quo that offers them little hope of advancement, and for a strain of liberalism that talks about redistributing wealth without delivering the more sweeping changes promised by Ocasio-Cortez and others like her.

A key principle of rainbow liberalism is that the solution to working-class woes is hiking taxes on the rich to finance a generous suite of wage subsidies, social services, and, for the truly ambitious, basic-income grants. But will white liberals be as enthusiastic about sharp increases in their taxes if they become something other than theoretical? Immigrants in New York, for instance, live in a state where the Democratic governor, Andrew Cuomo, recently championed a tax reform designed to sharply reduce the total tax burden facing his state’s wealthiest residents while stymieing New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s efforts to raise taxes on the city’s ultrarich. Cuomo did so as New York’s transit infrastructure was in crisis and rising rents were exposing tens of thousands of families to the risk of eviction.

These betrayals sting in the present. But in the near future, such efforts will be undertaken in the midst of “the Great Wealth Transfer”—in which trillions of dollars in accumulated cash, homes, and other assets will be transmitted from disproportionately white, native-born, college-educated Baby Boomers to their long-waiting heirs. In this context, a brown populism might emerge, one that is sharply to the left of today’s rainbow liberalism. Just as Donald Trump appeals to the ethnic self-interest of rural whites, a tribune of working-class Latinos could call attention to the dearth of Latinos in the uppermost echelons of American society and promise to do something drastic about it, such as redistributing the inherited wealth of privileged whites. In the post-civil-rights era, many charismatic African American politicians—and activists like Fred Hampton—promised to redress the racial injustices plaguing majority-black cities by confronting an ostensibly liberal white elite. Brown populism would pledge to do the same, but from a position of far greater electoral strength. Latinos already outnumber whites in California, and aren’t far behind in Texas; the electorates of the two most populous states will soon have a Latino plurality.

Yet brown populism could also take a rightward turn. The demands for decent wages and a modicum of respect will run counter to elites’ appetite for humble, disciplined workers willing to cater to their needs. This appetite has traditionally been met by immigration, and Latinos have for the most part been favorably disposed toward immigration policies that benefit their co-ethnics. Indeed, this shared enthusiasm for immigration has helped keep the rainbow coalition together. Now we find ourselves on the cusp of a possible reversal.

The foreign-born share of the Latino population is falling fast, and despite the ferocious controversies over Central American migration that have defined the Trump era thus far, the aging of Latin America ensures that future immigration flows will be less Latino in the years to come. For the foreseeable future, it is Africa and South Asia that, in light of their youthful and relatively fast-growing populations, will generate the greatest migratory pressures. And this shift could have seismic consequences.

According to the historian Brian Gratton, America’s major restrictionist movements have emerged in response to a dramatic increase in immigration levels coupled with a change in the ethnic origins of new immigrants. Both factors are important. If a dramatic increase in immigration levels occurs but natives by and large see the newcomers as their cultural kin, the reaction might be muted, as cultural affinity overrides other considerations. If a dramatic increase occurs and the newcomers are culturally distinct, however, intergroup tension is all but inevitable. Gratton’s thesis partly captures why older whites have been so resistant to Latino immigration.

But as Latino immigration slows, and as working-class Latino Americans come into their own politically, Gratton’s work leaves us with an irony-laden prediction about what is to come: A coalition of cosmopolitan whites, Asian Americans, and blacks may well fight to open the U.S. labor market to growing numbers of desperate people from Asia and Africa, whether out of class interest, ethnic loyalty, or devotion to rainbow liberalism as an ideology—but these new immigrants could be met by a coalition of working-class whites and Latinos who favor closed borders.

If you doubt that second-generation Latinos who are being raised in disadvantaged circumstances will ever embrace a more hard-edged politics, whether of the right or the left, I can hardly blame you. To believe it would be to accept that the ultimate consequence of working-class Latino immigration will be not merely the availability of low-cost services and the infusion of new cultural energies into our communities but also, in time, a wrenching redistribution of wealth and respect from privileged white liberals to a rising generation of justly dissatisfied outsiders. The question we face now is how to lay the groundwork for this future: Will we face up to the challenge of delivering the American dream to the millions of working-class newcomers who already live among us, even if that means sacrificing a measure of comfort in the present? Or will we continue to sentimentalize their struggles, confident in the self-serving belief that working-class immigrants and their children will forever accept second-class status?

This article appears in the September 2018 print edition with the headline “The Next Populist Revolution.”