When last we saw Jason Fitger, pained English professor at Payne University, his life was falling apart in epistolary form, in University of Minnesota creative writing professor Julie Schumacher’s 2014 cult hit Dear Committee Members, a Clarissa for the last days of the American university. Now, in the brutal sequel, The Shakespeare Requirement, Fitger’s back—and somehow, he’s been elected chair of his department of misanthropes and misfits, who hide in their crumbling offices while the Department of Economics takes over their building, room by room. If English doesn’t finalize its dystopian statement of vision—due months ago—they’ll never get funding again: for mousetraps, rental of their own recently monetized conference space, faculty, whatever. Trouble is, said statement has no mention of a Shakespeare requirement, and aging Shakespearean Dennis Cassovan has chosen exactly this hill to die on.

Can Fitger—himself distracted by a set of rotting teeth, a literal and figurative wasp’s nest, the university’s Godforsaken scheduling software, and, oh yes, his ex-wife Janet, with whom he is still desperately in love—find a way to resuscitate a department that might already be as dead as the Bard of Avon himself?

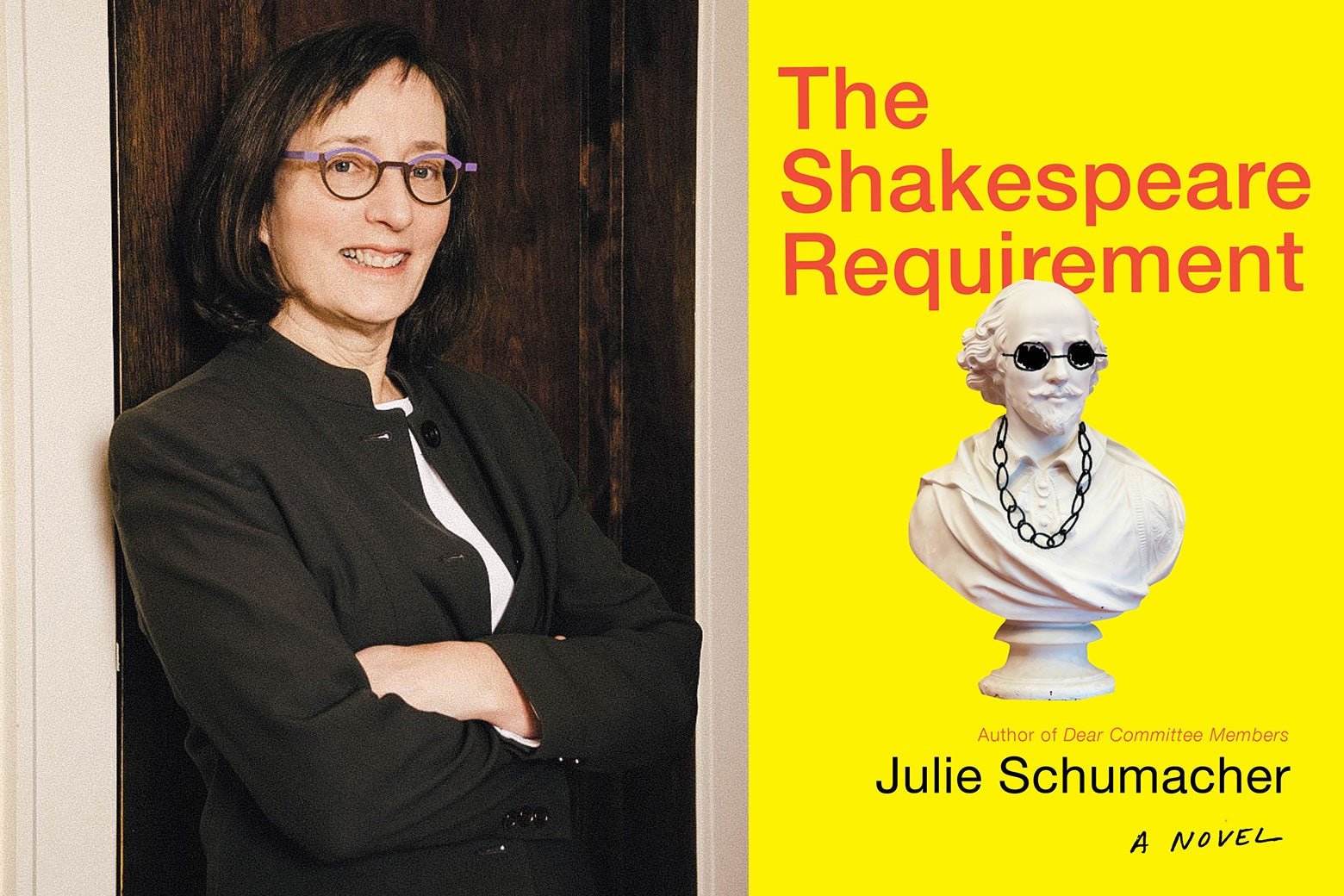

I recently emailed with Schumacher about Fitger, punctuation, and the ever-worsening state of the humanities in a thinking-averse America. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Rebecca Schuman: Jason Fitger is such a schmuck. He’s the quintessential mediocre white male academic, a stubborn luddite, and a philanderer. What made you want to spend so much time with him (again)?

Julie Schumacher: Yes, he can be a real schmuck. But I love Jason Fitger—otherwise I wouldn’t have wanted to spend another few years with him. Yes, he’s a luddite (as am I, and proud of it), and yes he’s mediocre (so what? most of us are), and yes, he broke up his marriage (to his eternal regret). But despite his numerous flaws, Fitger cares deeply about the things I care about: the state of the humanities at a time when enthusiasm for all things STEM is unbridled, higher education, student mental health and student debt, art, and the life of the mind. I see him as a Quixote figure—lacking common sense and personal and diplomatic skills, but continuing to fight.

Are you going to have to hide from your colleagues when this book comes out?

My colleagues have been wildly supportive. Some told me that I should put a suggestion box outside my office so that they could contribute their own wacky anecdotes as I write. In any case, I was very careful not to portray any real-life people.

But the beauty of a satire is that it forces truth to the surface. So if your department isn’t full of impossible weirdos like the characters in our book, then what truths are you forcing to the surface here?

A lot of academics are eccentric. And why not? These are people who spent a quarter century going to school, during those final years burrowing obsessively into an arcane topic, losing sleep and sacrificing relationships, eating vending-machine food in the library at 2 a.m. And then they get a job and are magically expected to become “team players” with other poorly socialized, obsessive people who may have radically different philosophies or approaches to a common topic about which they care deeply.

Critics of the literary humanities have two objections in direct conflict with each other: first, that you don’t teach anything relevant (Shakespeare, yawn!), and, second, the literary humanities only teach garbage identity politics, i.e. What happened to Shakespeare and the great Classics? How does this book educate a nonacademic public about this critique?

First, I think the cost of four years of schooling is driving much of the crisis. Education has become so expensive that students and their families are (understandably) asking whether the investment of time and money will be repaid; parents often urge their kids to concentrate on disciplines they see as practical. In terms of relevance, we need to ask ourselves about the broader purpose of education. In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, humans were bred and conditioned to fit tidily into the economy like pegs into holes. Shouldn’t we seek to educate the whole person and value students’ intellects and imaginations, rather than shape them like cogs for the wheel? My second answer to this would involve a defense of reading, in general (it’s becoming a lost art), and creative writing in particular.

I am definitely interested in your defense of reading and writing.

This is part and parcel of my disdain for technology. We are all so busy consulting our phones and snapping photos of ourselves that our tolerance for quiet and concentrated study is diminishing. Recently, I saw a woman pushing a stroller that had an iPad attached so that her baby, not even old enough to sit up, could tap the screen with his toes. Dystopia, I thought. One day I would love to teach a class that required students to check their devices at the door and find a comfortable spot and read silently for two hours, uninterrupted, prior to discussion. Wouldn’t that be terrific?

Dystopia, I say.

The more specific defense I would offer regards MFA programs in creative writing, which are regularly subject to gratuitous, tiresome abuse suggesting that they are in the business of producing cookie-cutter writers who publish similar work. I have never heard the same aspersions made against painters, actors, or musicians: Oh, another Juilliard graduate. MFA programs, when funded, offer up-and-coming artists a three-year life parenthesis during which they can step away from their jobs as waiters or clerks to concentrate on artistic endeavor. I suspect that many people are romantically attached to the idea of a writer suffering, à la Edgar Allen Poe, in order to garner material. Most people suffer enough as it is, so I reject that idea.

What about the contradiction inherent in the self-negating critique of literature departments?

It’s a totally contradictory stance: Why should students study the classics, when they could be learning something practical, such as accounting, instead? On the other hand, How dare a literature department minimize the study of Shakespeare and Chaucer and Milton in favor of Toni Morrison and Amy Tan? Critics of humanities departments want those departments to be traditional in scope, and then they want them to be condemned as irrelevant and quaint.

Have you ever had an academic nemesis?

I will limit myself to saying that I have sat through faculty meetings that involved twentysomething professors attempting collectively to revise a department document. There is nothing more surreal than a room full of English faculty arguing about syntax and the placement of a semicolon.

On the subject of punctuation: I have had to delete the now-antiquated second space after every period you have typed in this conversation. Score one for the luddite.

The perfectly good reason for the second space: It gives older eyes in particular a quick or automatic cue that the end of a sentence has been reached. The single space provides no such cue or clarity, and a period can too easily be confused with a comma. The eye takes in a paragraph at a glance and, with the double spaces, immediately perceives its components before beginning to read. Clear and lovely. The single space, on the other hand, is crowded and gives an impression of monotonous prose.

But come on, you can’t be that much of a luddite! You’re emailing me right now. Fitger is the kind of selective luddite that stresses me out—namely, he does use a computer when he feels like it, but he refuses to use the university’s scheduling software, and all these well-meaning students are not getting appointments with him, and he’s missing all this important stuff he needs to do as chair!

Yes, I use email and I use a computer. I even have a cellphone, though most of the time it lives in my sock drawer, with the mismatched socks that lost their mates in the dryer. And I adamantly refuse to use our university’s Google Calendar system. My schedule and whereabouts are my business and no one else’s.

I am stressed out right now, just talking about this.

As for “missing all this stuff” — please, god, let me miss more of it. I aspire to be 95 percent unplugged.

The Shakespeare Requirement by Julie Schumacher. Doubleday.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.

Correction, Aug. 13, 2018: The credit for the author photo on this piece was originally misattributed to Julie Schumacher herself.