How Trump Radicalized ICE

A long-running inferiority complex, vast statutory power, a chilling new directive from the top—inside America’s unfolding immigration tragedy

Settling into a sense of safety is hard when your life’s catalog of memories teaches you the opposite lesson. Imagine: You fled from a government militia intent on murdering you; swam across a river with the uncertain hope of sanctuary on the far bank; had the dawning realization that you could never return to your village, because it had been torched; and heard pervasive rumors of former neighbors being raped and enslaved. Imagine that, following all this, you then found yourself in New York City, with travel documents that were unreliable at best.

This is the shared narrative of thousands of emigrants from the West African nation of Mauritania. The country is ruled by Arabs, but these refugees were members of a black subpopulation that speaks its own languages. In 1989, in a fit of nationalism, the Mauritanian government came to consider these differences capital offenses. It arrested, tortured, and violently expelled many black citizens. The country forcibly displaced more than 70,000 of them and rescinded their citizenship. Those who remained behind fared no better. Approximately 43,000 black Mauritanians are now enslaved—by percentage, one of the largest enslaved populations in the world.

After years of rootless wandering—through makeshift camps, through the villages and cities of Senegal—some of the Mauritanian emigrants slowly began arriving in the United States in the late 1990s. They were not yet adept in English, and were unworldly in almost every respect. But serendipity—and the prospect of jobs—soon transplanted their community of roughly 3,000 to Columbus, Ohio, where they clustered mostly in neighborhoods near a long boulevard that bore a fateful name: Refugee Road. It commemorated a moment at the start of the 19th century, when Ohio had extended its arms to accept another influx of strangers, providing tracts of land to Canadians who had expressed sympathy for the American Revolution.

Refugee Road wasn’t paved with gold, but in the early years of this century, it fulfilled the promise of its name. The Mauritanians converted an old grocery store into a cavernous, blue-carpeted mosque. They opened restaurants that served familiar fish and rice dishes, and stores that sold CDs and sodas imported from across Africa.

Over time, as the new arrivals gave birth to American citizens and became fans of the Ohio State Buckeyes and the Cleveland Cavaliers, they mentally buried the fact that their presence in America had never been fully sanctioned. When they had arrived in New York, many of them had paid an English-speaking compatriot to fill out their application for asylum. But instead of recording their individual stories in specific detail, the man simply cut and pasted together generic narratives. (It is not uncommon for new arrivals to the United States, desperate and naive, to fall prey to such scams.) A year or two after the refugees arrived in the country, judges reviewed their cases and, noticing the suspicious repetitions, accused a number of them of fraud and ordered them deported.

But those deportation orders never amounted to more than paper pronouncements. Where would Immigration and Customs Enforcement even send them? The Mauritanian government had erased the refugees from its databases and refused to issue them travel documents. It had no interest in taking back the villagers it had so violently removed. So ice let their cases slide. They were required to regularly report to the agency’s local office and to maintain a record of letter-perfect compliance with the law. But as the years passed, the threat of deportation seemed ever less ominous.

Then came the election of Donald Trump. Suddenly, in the warehouses where many of the Mauritanians worked, white colleagues took them aside and warned them that their lives were likely to get worse. The early days of the administration gave substance to these cautions. The first thing to change was the frequency of their summonses to ice. During the Obama administration, many of the Mauritanians had been required to “check in” about once a year. Abruptly, ice instructed them to appear more often, some of them every month. ice officers began visiting their homes on occasion. Like the cable company, they would provide a six-hour window during which to expect a visit—a requirement that meant days off from work and disrupted life routines. The Mauritanians say that when they met with ice, they were told the U.S. had finally persuaded their government to readmit them—a small part of a global push by the State Department to remove any diplomatic obstacles to deportation.

Fear is a contagion that spreads quickly. One ice officer warned some Mauritanians sympathetically, “It’s not a matter of if you’ll be deported, but when.” Another flatly said, “My job is to get you to leave this country.” At meetings, officers would insist that the immigrants go to the Mauritanian consulate and apply for passports to return to the very country whose government had attempted to murder them.

One afternoon this spring, I sat in the bare conference room of the Columbus mosque after Friday prayer, an occasion for which men dress in traditional garb: brightly colored robes and scarves wrapped around their heads. The imam asked those who were comfortable to share their stories with me. Congregants lined up outside the door.

One by one, the Mauritanians described to me the preparations they had made for a quick exit. Some said that they had already sold their homes; others had liquidated their 401(k)s. Everyone I spoke with could name at least one friend who had taken a bus to the Canadian border and applied for asylum there, rather than risk further appointments with ice.

A lithe, haggard man named Thierno told me that his brother had been detained by ice, awaiting deportation, for several months now. The Mauritanians considered it a terrible portent that the agency had chosen to focus its attention on Thierno’s brother—a businessman and philanthropically minded benefactor of the mosque. If he was vulnerable, then nobody was safe. Eyes watering, Thierno showed me a video on his iPhone of the fate he feared for his brother: a tight shot of a black Mauritanian left behind in the old country. His face was swollen from a beating, and he was begging for mercy. “I’m going to sleep with your wife!” a voice shouts at him, before a hand appears on-screen and slaps him over and over.

In 21st-century America, it is difficult to conjure the possibility of the federal government taking an eraser to the map and scrubbing away an entire ethnic group. I had arrived in Columbus at the suggestion of a Cleveland-based lawyer named David Leopold, a former president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association. Leopold has kept in touch with an old client who attends the Mauritanian mosque. When he mentioned the community’s plight to me, he called it “ethnic cleansing”—which initially sounded like wild hyperbole. But on each of my trips back to Columbus, I heard new stories of departures to Canada—and about others who had left for New York, where hiding from ice is easier in the shadows of the big city. The refugees were fleeing Refugee Road.

Video: Fleeing ICE

Since taking office, Donald Trump has regularly thundered against the “deep state.” With the term, he means to evoke a cabal of bureaucrats burrowed within law enforcement, the intelligence community, and regulatory agencies, a nebulous elite that will stop at nothing to countermand his will—and, by extension, that of the people.

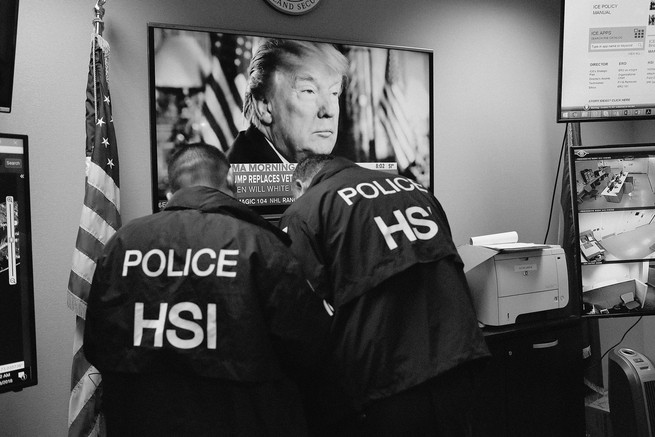

But one segment of the deep state stepped forward early and openly to profess its enthusiasm for Trump. Through their union, employees of ice endorsed Trump’s candidacy in September 2016, the first time the organization had ever lent its support to a presidential contender. When Trump prevailed in the election, the soon-to-be-named head of ice triumphantly declared that it would finally have the backing of a president who would let the agency do its job. He’s “taking the handcuffs off,” said Thomas Homan, who served as ice’s acting director under Trump until his retirement in June, using a phrase that has become a common trope within the agency. “When Trump won, [some officers] thumped their chest as if they had just won the Super Bowl,” a former ice official told me.

Whatever else Trump has accomplished for ice, he has ended its relative anonymity. His administration’s “zero tolerance” immigration regime has triggered a noisy debate about the organizations he has deployed to enforce his policies. For weeks this spring, the nation watched as officers took children from their parents after they had crossed the U.S.–Mexico border in search of asylum. Although ice played only a supporting role in the family-separation debacle—the task was performed principally by U.S. Customs and Border Protection—the agency has emerged as a shorthand for what critics say is wrong with Trump’s immigration agenda. Virtually every Democratic politician hoping to flash his or her progressive bona fides has called for ice’s abolition.

The history of the agency is still a brief one. When terrorists struck the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, ice didn’t exist. In the Justice Department, there was the old Immigration and Naturalization Service. But while the mission of INS had always included the deportation of undocumented immigrants—and it occasionally staged significant workplace raids—it never had a large force that would enable their systematic removal from the nation’s interior.

But following the shock of 9/11, ice was created as part of the Department of Homeland Security, into which Congress awkwardly stuffed a slew of previously unrelated executive-branch agencies: the Secret Service, the Transportation Security Administration, the Coast Guard. Upon its creation, DHS became the third-largest of all Cabinet departments, and its assembly could be generously described as higgledy-piggledy. ice is perhaps the clearest example of where such muddied, heavily politicized policy making can lead.

Since its official designation, in 2003, as a successor to INS, ice has grown at a remarkable clip for a peacetime bureaucracy. By the beginning of Barack Obama’s second term, immigration had become one of the highest priorities of federal law enforcement: Half of all federal prosecutions were for immigration-related crimes. In 2012, Congress appropriated $18 billion for immigration enforcement. It spent $14 billion for all the other major criminal law-enforcement agencies combined: the FBI; the Drug Enforcement Administration; the Secret Service; the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives; and the U.S. Marshals Service.

ice quickly built a sprawling, logistically intricate infrastructure comprising detention facilities, an international-transit arm, and monitoring technology. This apparatus relies heavily on private contractors. Created at the height of the federal government’s outsourcing mania, DHS employs more outside contractors than actual federal employees. Last year, these companies—which include the Geo Group and CoreCivic—spent at least $3 million on lobbying and influence peddling. To take one small example: Owners of ice’s private detention facilities were generous donors to Trump’s inauguration, contributing $500,000 for the occasion.

An organization devoted to enforcing immigration laws will always be reflexively and perhaps unfairly cast as a villain. But borders are a fundamental prerogative of the nation-state: The policing of them is a matter of national security, and a functioning polity maintains orderly processes for admitting some immigrants and turning others away. By definition, elements of this mission are exclusionary and hard-hearted. The liberal immigration policies practiced within the European Union have shown how what seems like a simple generosity of spirit can also be deeply destabilizing. A balance needs to be found.

Still, ice, as currently conceived, represents a profound deviation in the long history of American immigration. On many occasions, America has closed its doors to both desperate refugees and eager strivers. But once immigrants have reached our shores, settled in, raised families, and started businesses, all without breaking any laws, the government has almost never chased them away in meaningful numbers. In 1954, Dwight Eisenhower’s Operation Wetback—this was its official designation—removed more than 1 million Mexican immigrants. It is remembered precisely because it was so dissonant with America’s self-styled identity as a nation of immigrants.

ice, however, is assigned the task of removing undocumented immigrants from the country’s interior, and it has approached this mission with cold, bureaucratic efficiency. Until recently, the agency had a congressional mandate to maintain up to 34,000 beds in detention centers on any given day with which to detain undocumented immigrants. Once an immigrant enters the system, she is known by her case number. Her ill intentions are frequently presumed, and she will find it exceedingly difficult to plead her case, or even to know what rights she has.

Approximately 11 million undocumented immigrants currently live in this country, a number larger than the population of Sweden. Two-thirds of them have resided in the U.S. for a decade or longer. The laws on the books endow ice with the technical authority to deport almost every single one of them. Trump’s predecessors, Barack Obama and George W. Bush, allowed for a measure of compassion, permitting prosecutors and judges to stay the removals of some defendants in immigration court, and encouraging a rigorous focus on serious criminals. Congress, for its part, has for nearly two decades offered broad, bipartisan support for the grand bargain known as comprehensive immigration reform. The point of such legislation is to balance tough enforcement of the law with a path to amnesty for undocumented immigrants and the ultimate possibility of citizenship.

Yet no politician has ever quite summoned the will to overcome the systematic obstacles that block reform. Democrats didn’t make it a top priority when they briefly controlled Congress during Obama’s first term, and Republican reformers have again and again been stymied by anti-immigration hard-liners in the House. A comprehensive reform bill passed the Senate in 2013 by a resounding 68–32 margin, but then-Speaker John Boehner refused to allow it a vote in the House. The 2016 GOP presidential hopeful Marco Rubio went from staking his political identity on immigration reform to suggesting that he’d never truly supported the reforms in the first place.

Under the current administration, many of the formal restraints on ice have been removed. In the first eight months of the Trump presidency, ice increased arrests by 42 percent. Immigration enforcement has been handed over to a small clique of militant anti-immigration wonks. This group has carefully studied the apparatus it now controls. It knows that the best strategy for accomplishing its goal of driving out undocumented immigrants is quite simply the cultivation of fear. And it knows that the latent power of ice, amassed with the tacit assent of both parties, has yet to be fully realized.

On a last-minute trip to Columbus, I booked a room in a boutique hotel on the upper floors of a newly refurbished Art Deco skyscraper. I had arranged to meet a 20-something African immigrant, whom I will call Ismael, and his lawyer at the Starbucks in the lobby the next morning; I would accompany them to Ismael’s regularly scheduled appointment with ice.

Short, gaunt, and taciturn, Ismael came from Africa last year by way of a smuggling route through Mexico—a circuitous trek that culminated in his capture while crossing into California and several months in ice detention. When I met Ismael, he rolled up a snug-fitting leg of his black jeans to show me the monitoring bracelet strapped around his bony ankle—a condition of his release. He had also received permission to relocate to his cousin’s apartment in Columbus. Because ice prohibited him from working while he awaited authorization papers, Ismael had improved his English by watching copious television. It was good enough for him to tell me, “I came to America to be free. This is not freedom.” As we made our way to ice, I was startled to discover that we would not be leaving the premises. ice had office space on the third floor of the building my hotel occupied. It was a small but jolting illustration of the ubiquity of the relatively new agency.

Unsurprisingly, the waiting room at ice was not part of the skyscraper’s upscale refurbishment. It was like a dentist’s office stripped of magazines, posters that importune flossing, and pretty much any other splash of color. A small, older woman from Central America wandered through the perfectly quiet room with a piece of paper stapled to a manila envelope: “I don’t speak English. Please help me.”

A heavy, locked door separates the waiting room from ice’s main office, where officers interview immigrants and sometimes detain them. When a functionary in a flannel shirt opened the door and summoned Ismael, his lawyer rose to accompany him. But the officer waved a forefinger in her direction. “Sorry, lawyers aren’t allowed back,” he told her. A look of confusion compressed her face. “But I’ve been allowed back in the past. I think I’m allowed back,” she told him. “Can I talk to a supervisor?”

Two minutes later, an officer with a shaved head, a black Under Armour hoodie, and a gun on his belt leaned his body through the door to stare intently at Ismael. “Why have you been working?” he asked. “We know you’ve been working.” It appeared to be an annoyed response to the lawyer’s resistance, hurled without evidence, perhaps in the hopes of provoking a self-incriminating response. It seemed of a piece with the fraught atmosphere in the waiting room. Earlier, there had been an announcement that a car was parked illegally outside and needed to be moved. Ismael’s lawyer had leaned over to tell me that this would be widely presumed to be another trick: Many immigrants under ice scrutiny are not allowed to drive.

When immigration lawyers in Columbus deal with ice, they are tentative, fretful that anything that might reek of complaint could provoke ice into seeking retribution against their clients. So Ismael’s lawyer struck a stance of studied conciliation. As she gently explained herself, Ismael disappeared behind the door for his appointment and another manager emerged. He said that the man handling Ismael’s “intensive supervision” worked for a private contractor hired by ice, and that the company’s contract with the federal government prohibited lawyers from attending its sessions with immigrants. “Just out of curiosity,” the lawyer asked, “can I see a copy of the rules?” The supervisor returned with a sheet of paper. He pointed to the crucial passage in a section enumerating “participant rights.” It described “the right to confidentiality with the exception of information requested by ice.” The lawyer flashed me a furtive smirk as she refrained from commenting on the bravura display of doublespeak: Ismael had been denied his right to an attorney in order to protect his confidentiality. But the manager, a Latino man with an untucked shirt and glasses, earnestly attempted to explain himself. He said that he wanted to help, and he mentioned the possibility of Ismael getting a work permit soon. “Look,” he said, “I’m very sympathetic to him.”

When Ismael returned to the waiting room, he supplied one-word answers to the lawyer’s questions about the meeting. It had ultimately amounted to little more than a rote brush with the system. Still, it left the lingering sense that a terrible outcome had merely been postponed—which was perhaps the whole point.

No one, as a child, dreams about growing up to deport undocumented immigrants. Some 6,000 officers work in the Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) wing of ice, but this is not always a first-choice career option. “Many in ice applied to other agencies that rank higher in law-enforcement prestige,” says David Martin, a scholar of immigration law who served in the Clinton and Obama administrations. The ranks of ice are drawn in large part from retired members of the military and from former Border Patrol agents, who prefer the metropolitan locations of ice offices to the remote outposts dotting the nation’s southern border. The job is a solid option for high-school graduates, who are not eligible to apply to federal agencies that require a college education. It makes for an accessible entry point into federal law enforcement, a trajectory that comes with job security and decent pay, and perhaps the hope of someday storming buildings or standing in the backdrop of press conferences, beside tables brimming with seized contraband. Such reveries are easy enough to entertain, until the first day on the job.

ice consistently ranks among the worst workplaces in the federal government. In 2016, the organization ranked 299th on a list of 305 federal agencies in a survey of employee satisfaction. Even as Trump smothered the organization with praise and endowed it with broader responsibilities, ice still placed 288th last year.

The culture of ice is defined by a bureaucratic caste system—the sort of hierarchical distinctions that seem arcane and petty from the outside, but are essential to those on the inside. When ice was created, 15 years ago, two distinct and disparate workforces merged into one. The Immigration part of the agency’s name refers mostly to deportation officers who came over from the freshly dismantled Immigration and Naturalization Service. The Customs part of the name refers to investigators imported from the Treasury Department. This was a shotgun marriage, filled with bickering and enmity from the start. The customs investigators had adored their old institutional home and the built-in respect it accorded them. They were given little warning before being moved to a new headquarters, with new supervisors, a nebulous mission, and colleagues they considered their professional inferiors. When I interviewed one of the customs investigators, who later had a top job at ice, he still referred to the “unfortunate events of March 1, 2003”—the day ice came into official existence.

After several false starts, the customs investigators were eventually restyled into a unit called Homeland Security Investigations. HSI managed to consistently find its way to glamorous cases that involved transnational crime—software piracy, child pornography, the bust of the Mexican kingpin Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera, the investigation of terrorist bombings in Paris. But for all their efforts, HSI agents still found themselves dogged by their ties to ERO and the emotionally charged issue of immigration. They were shunned by police in big cities that refused to cooperate with ice, not allowing for the fact that HSI functioned as its own distinct entity. Indeed, this summer 19 HSI agents signed a letter to Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, asking her to officially separate their division from ice. The agents wrote: “HSI’s investigations have been perceived as targeting undocumented aliens, instead of the transnational criminal organizations.” They explained that they felt HSI was paying a reputational price for its connection to ERO.

There is arguably a certain institutional hauteur to HSI. “They think of themselves as aristocrats,” one former homeland-security official told me. Among other benefits, working for HSI brings the rank of “special agent”—what’s known in federal guidelines as 1811 status—which sets officers on the same level as FBI agents. Meanwhile, ERO officers carry an 1801 classification. This position typically comes with a less favorable pay scale and limited powers. For instance, these officers are not allowed to execute search warrants.

An ERO officer’s day-to-day existence is at a distant remove from the televised image of federal law enforcement. It often consists of paper-pushing and processing immigrants through the various stations of deportation. In many instances, when ERO officers are assigned to detain criminals who are at large, they brush up against bureaucratic limitations. “You go bang on a door and they’re not there,” John Sandweg, a former acting director of ice, told me. Even if the person is home, he has the right to refrain from letting officers inside. If that happens, officers have no recourse other than to sit outside and wait.

“Regular cops get frustrated when a plea agreement is too soft,” says Sandweg. “With ERO, about 50 percent of the people you arrest will still be in the country a year later.” This is one of the many consequences of a system that—whatever one’s political views on immigration—has obvious elements of dysfunction. ice’s capacity to detain immigrants long ago outstripped the capacity of courts to process them. Immigration courts currently have a backlog of 700,000 cases, which means that someone might wait several years before ever seeing a judge. A sense of futility, therefore, has become a prevailing ethos for much of the ice rank and file. One former agent recalls learning a maxim on his first day on the job: “It’s not over until the alien wins.”

Even as some ice officers suffer from a sense of their own impotence, the outside world often depicts them as heartless jackboots. Thomas Homan has described how, as acting director of the agency, he would wake up every morning and read the latest complaints and negative coverage from the American Civil Liberties Union and mainstream media. And those aren’t the only sources of criticism. Most ice agents work in cities. Many of them are themselves Latino or have married an immigrant. As John Amaya, a former deputy chief of staff of ice, told me, “Their kids go to school and hear things; they go to the grocery store and hear shit. They are not immune.”

When I asked how ice responds to complaints and criticism, I was repeatedly told that officers can have genuine qualms about their work. Like any large organization, ice has its share of bad apples. But officials from the Obama administration vociferously countered any notion that ice is teeming with racists. Carlos Guevara, who served as an adviser to the homeland-security leadership, told me, “There are a lot of good officers … And I don’t think a lot of them feel great about picking up abuelita”—someone’s grandmother—“or somebody who’s been here for 20 years, much less being part of a policy separating kids from parents.”

To navigate this moral thicket, ice officers tell themselves comforting stories. The agency was founded, after all, in the aftermath of 9/11, when the government had failed to prevent evildoers from infiltrating the homeland and killing thousands. As one former ice official told me, “You numb yourself by saying everything we do has a national-security focus. By God, if we let this one slip by, it’s the tip of the iceberg. We never know when we’re confronted with the real threat.” The likelihood of that genuine threat, of course, is very much open to debate. Statistically speaking, an immigrant who has lived in the United States for decades, has an immaculate criminal record, and comes from Central America (like many ice targets) poses so negligible a national-security threat that it is virtually nonexistent. No immigrant from the region has ever committed a terrorist attack on U.S. soil, which is something that cannot be said of native-born Americans.

This fragile institutional psyche was on full display in ice’s obstreperous response to Obama. During the first term of his presidency, Obama pursued an aggressive policy of immigration enforcement. As late as 2013, he expelled 438,000 undocumented immigrants, a far higher number than any other recent administration did. This extreme crackdown was intended as a down payment on comprehensive immigration reform. Republicans had clamored for proof of Obama’s sincere commitment to enforcement, and he supplied it. Alas, that down payment would never be recouped. Immigration reform collapsed thanks to the guerrilla tactics of the GOP hard-liners in the House. And so, in the face of congressional inaction, Obama set about steering ice toward a more compassionate strategy. He wanted to give the agency a set of explicit and rigid priorities for whom it would detain and deport. Previously, almost any undocumented immigrant had been fair game. Now Obama set about focusing ice’s efforts on serious criminals and recent arrivals. By the middle of his second term, the administration had figured out how to translate its priorities into bureaucratic reality. It supplied ice with clear procedures—with checklists and paperwork—to ensure that the organization hewed closely to the new goals.

In the parlance of certain factions of ice, these Obama-era priorities were the “handcuffs” that prevented officers from doing their job. At various moments during these years, a broad swath of ice officers behaved as a rogue unit within the federal government. In 2012, after Obama proposed his enforcement priorities, the union representing ice officers initially didn’t allow its members to attend training sessions that inculcated the new approach. When Obama issued his plans for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (daca) that same year, the head of the union, Chris Crane, sued top administration officials to block the move. Crane became a favorite witness of then-Senator Jeff Sessions, who called Crane “an American hero.”

Upon entering the political scene, Donald Trump promoted himself as ice’s salvation. By flaying Obama’s immigration policy with uncharacteristic consistency and specificity, he spoke to the deep resentments of many ERO officers. Lavishing them with praise—“We respect and cherish our ice officers”—he constantly asserted their importance to public safety. When the ice union assembled to endorse a presidential candidate, Trump received 95 percent of the vote. And he returned the favor: During a speech exactly five days after his inauguration, the president pointed to Crane and declared, “You guys are about to be very, very busy doing your jobs.”

We know all the common knocks against government: how it overcomplicates tasks, how it resists change, how it has a remarkable capacity for inventing inefficiencies. But ice has quickly created a system of incredible scale, an industrialized process for removing human beings from the United States.

Take the example of ice Air. Twelve years ago, ice set about creating an internal mechanism for transporting deportees back to their native lands by establishing its own airline. ice Air has access to 10 planes, most of them Boeing 737s, each capable of carrying 135 deportees, dispatched from airports in five hub cities: Mesa, Arizona; San Antonio and Brownsville, Texas; Alexandria, Louisiana; and Miami. Maps like the ones found in seat-back pockets show the arcing trajectories of ice Air’s most common routes, extending out across the hemisphere. (In 2016, ice Air flew 317 trips to Guatemala, its top destination.) Like most airlines, ice Air has a baggage limit: no more than 40 pounds. Unlike most airlines, ice Air forbids passengers from wearing belts and shoelaces, for fear they might use them to commit suicide. If nothing goes amiss, stewards serve granola bars and water, or on longer flights a full meal. Sometimes they unlock the handcuffs of the deportees who have been shackled.

Yet provisions on ice Air have been a source of controversy. Last winter, a flight carrying 92 Somalians made a pit stop in Dakar, Senegal. During the layover, the plane waited for a fresh crew, which was delayed due to issues at its hotel. So the plane reportedly sat on the runway for almost 24 hours, the passengers never disembarking. ice has disputed accounts of the long delay, but some of the Somalians say that the agency failed to supply them with sufficient food and drink, and that because of faulty air-conditioning, they found breathing difficult. According to one account, they weren’t allowed to walk the aisles to the lavatory, so they relied on empty water bottles—and when their urine outpaced the supply of water bottles, they were forced to wet themselves.

To coordinate ice Air requires a certain logistical genius, especially given the organization’s aim—familiar to anyone who relies on commercial air travel—of filling as many seats as possible on each of its flights. (To execute such deportations, ice Air prefers to charter its own flights; the agency tries to avoid placing deportees on commercial flights, because airlines won’t board a passenger who actively refuses to fly.) One former ice official recalls a conversation in which a colleague boasted of an especially complex deportation to Gaza, which required traversing the Sinai Peninsula. He said the agency has felt intense congressional pressure to demonstrate that no nationality, no matter how small its presence in the United States, is beyond its deportation capacity.

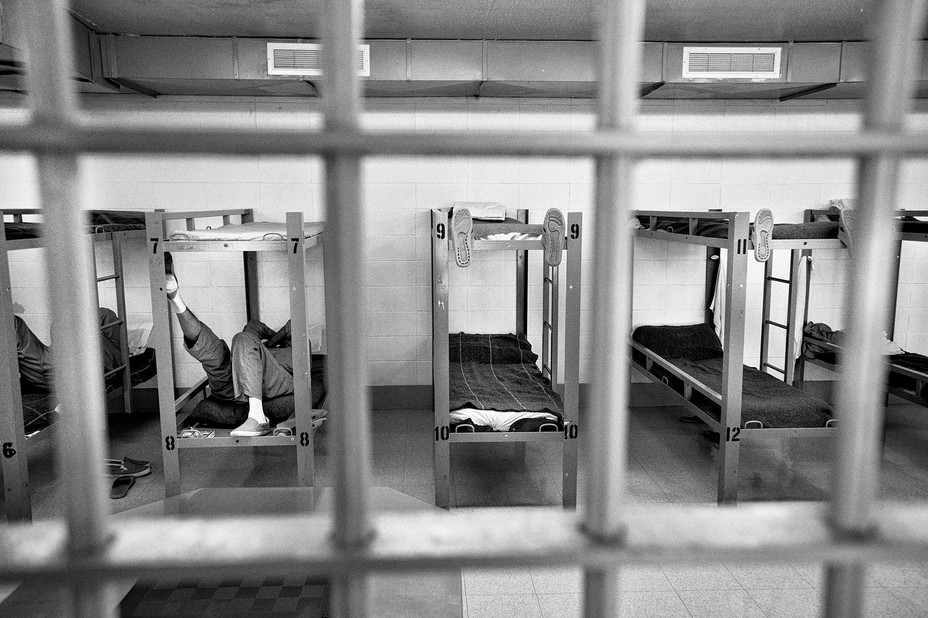

ice has numeric goals, and it goes to great lengths to achieve them. Among the most important of these goals is the drive to constantly run its detention facilities at maximum capacity. In 2004, Congress directed ice to add 8,000 new beds a year. (In 1994, the government maintained a daily average of 6,785 detainees; this year, the expected average is 40,520.) This required a massive investment in detention, which Congress wanted to ensure didn’t go to waste. In 2009, Robert Byrd, the late Democratic senator from West Virginia, quietly added a provision to an appropriations bill mandating that ice “maintain a level of not less than 33,400 detention beds.” The provision was never debated and left room for competing interpretations. But for large stretches of the Obama years, Byrd’s amendment was regarded as an obligatory quota. (Last year Congress finally removed the Byrd quota, but Trump’s goals for detention far outstrip anything Congress has ever mandated.)

It’s one thing for a city to require cops to issue a minimum number of parking tickets; it’s another for the federal government to proscribe a daily goal for the number of human beings it will deprive of liberty. But the system that Byrd helped enshrine encourages precisely that. Jeremy Jong, an attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center, described to me a conversation he had with an ice official at a Louisiana detention facility. The official bragged that “he always did his best to fulfill his contractual obligation to keep the center’s beds full of inventory.”

The description of immigrants as “inventory” is a logical extension of how ice has outsourced detention to private firms, for which each confinement represents additional profit. Detention is a boom industry, backed by such megafunds as Vanguard and BlackRock, and it has experienced a decade of steroidal growth. In the months following Trump’s election, the stock prices of the biggest detention companies, the Geo Group and CoreCivic, rose by more than 100 percent. (Those prices have leveled out since then.) Last year, the bipartisan army of lobbyists employed by the Geo Group and its primary competitors included power firms Akin Gump and the Gephardt Group, founded by former House Majority Leader Richard Gephardt. That fall, the Geo Group celebrated its good fortune by holding its annual leadership conference at the Trump National Doral resort, in Miami.

Both CoreCivic and the Geo Group maintain that they do not lobby for or promote specific legislation shaping immigration policy. But according to NPR, the detention industry donated money to 30 of the 36 co-sponsors of the infamous S.B. 1070, a broad and harsh crackdown on undocumented immigrants, which then–Arizona Governor Jan Brewer signed into law in 2010. Additionally, two of Brewer’s top advisers were former lobbyists for CoreCivic. (The bill was eventually shredded by the courts on constitutional grounds.)

There are, of course, genuine public-policy rationales for ice’s contracting with private companies for detention facilities. The principal alternative is to rely on county jails, where ice reportedly rents beds for $130 a night. The detention system is supposedly encoded in civil law, but jails are inherently rooted in the criminal system. Many of the immigrants detained in jails wear brightly colored jumpsuits and live surrounded by bars and wires. Many of these jails, unlike the private facilities, have no capacity for handling non-English speakers.

Still, the private facilities are run with the explicit goal of profit—a motive that can come at the cost of the well-being of detainees. Several are in remote, rural areas, where land and labor come especially cheap. One of the primary private facilities in the South is in Lumpkin, Georgia, on the Alabama border, 140 miles from Atlanta. Civil detention is explicitly not meant to be punitive—merely a necessary step in the administrative process of deportation—but the distance to some facilities makes regular visits from relatives extremely difficult. Immigration lawyers told me that they tend not to take cases in such facilities, because access would be so difficult. Marty Rosenbluth, a lawyer from North Carolina, relocated to Lumpkin. “I’m currently the only attorney doing defense against removal cases, that I know of, between Lumpkin and Atlanta,” he told me. “I actually opened up a one-room B&B in my house to try and lure attorneys down here, since part of their excuse for not taking cases here is that the nearest hotels are an hour drive.” Even with his presence, a 2015 University of Pennsylvania Law Review study found that only 6 percent of detainees in the facility have a lawyer. Nationwide, the figure isn’t much better: 14 percent. And without a lawyer, their chances of victory in immigration court slump from slim (21 percent) to nearly hopeless (2 percent).

Private detention companies’ contracts with ice stipulate that they uphold a set of rigorous standards, but they of course seek to tamp down costs, which means that they may skimp on basic care for detainees. Take the CoreCivic facility in Elizabeth, New Jersey, which a group of lawyers and health professionals assembled by Human Rights First toured last year. What they discovered on their visits were reports of maggots in the showers and raw food served in the cafeteria, not to mention drinking water described as “pure bleach.” Several detainees said they avoid asking for dental care because the dentist at the facility only performs extractions, even when a filling would do. Mental-health treatment commonly includes “bibliotherapy”—the assignment of self-help books—despite the obvious fact that prolonged detention can bring stress and depression. CoreCivic maintains that Human Rights First’s report contained “numerous false and misleading allegations.” But these aren’t merely the stray observations of an activist group. In December, John V. Kelly, the acting inspector general of the Department of Homeland Security, issued a comprehensive report based on a series of surprise visits to detention facilities. His findings read: “We identified problems that undermine the protection of detainees’ rights, their humane treatment, and the provision of a safe and healthy environment.”

Like many bureaucracies, ice strains for growth. When the agency was created, it employed just over 2,700 deportation officers, roughly the same number of employees as the San Diego police department. That workforce has since doubled, and the organization’s ambitions have ballooned. Beyond its own budget and its network of private contractors, ice has availed itself of a provision in an immigration law signed by Bill Clinton in 1996. That provision empowered the federal government to partner with state and local police. In effect, this means ice can deputize police to enforce federal immigration laws. Not every jurisdiction has wanted to align itself with ice—indeed, most major cities have strenuously resisted, especially in the Trump era. But plenty of local police forces, many of them in suburban counties, have gladly taken up ice’s offer to collaborate.

Gwinnett County, in northern Georgia, once epitomized the old rural South, sparsely populated and largely white. But over the past few decades, its population has exploded in both size and racial diversity. Demographers say the county’s white majority is on track to be displaced by 2040. When Trump signed an executive order allowing ice to detain essentially any undocumented immigrants it encounters, the Gwinnett County police responded enthusiastically. The number of undocumented immigrants transferred to ice from local jails jumped by 248 percent during the first four months of Trump’s presidency, relative to the prior year. Gwinnett police weren’t rounding up dangerous gang members: When the Migration Policy Institute studied the new pattern of enforcement, it found that police were primarily arresting immigrants for traffic violations before handing them over to ice.

The early Trump era has witnessed wave after wave of seismic policy making related to immigration—the Muslim ban initially undertaken in his very first week in office, the rescission of daca, the separation of families at the border. Amid the frantic attention these shifts have generated, it’s easy to lose track of the smaller changes that have been taking place. But with them, the administration has devised a scheme intended to unnerve undocumented immigrants by creating an overall tone of inhospitality and menace.

Where immigration is concerned, Trump has installed a group of committed ideologues with a deep understanding of the extensive law-enforcement machinery they now control. One especially skilled participant is L. Francis Cissna, the head of the Office of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Cissna is a longtime bureaucrat at the Department of Homeland Security who styled himself a dissident during the Obama years. In 2015, he temporarily left the department to work “on detail” for Republican Senator Chuck Grassley. An MIT graduate and the son of a Peruvian immigrant, Cissna began his career as a Foreign Service officer in Haiti and then Sweden. Over time, he became a policy savant; even his ideological opponents confess that he is more fluent in the immigration system’s intricacies than they are.

From his perch in the Trump administration, Cissna has repeatedly broadcast the agency’s new attitude toward immigration. In February, he rewrote its mission statement, erasing a phrase that described the United States as a “nation of immigrants.” He explained the change by stating that he wanted to emphasize the “commitment we have to the American people”—as if there were intellectual tension between the two sentiments. Then, in June, he announced the opening of an office that would review the files of naturalized citizens, reexamining fingerprints and hunting for hints of fraud that might enable the revocation of citizenship.

Cissna is part of a close-knit coterie of former Capitol Hill staffers whom Trump has placed in charge of the immigration system. Before Trump took office, the group clustered in the offices of the conservative politicians most committed to restrictive immigration policy, especially Senators Grassley and Sessions. Even in a time when GOP policy on immigration had swung far to the right, these staffers—Stephen Miller, now a White House senior adviser, is the most famous of the bunch—existed far outside the party’s mainstream. According to former colleagues, the offices of senators such as John McCain and Marco Rubio would lose patience with them because of their eagerness to detonate any viable version of immigration reform. “They are a little cabal,” one Republican staffer who dealt closely with them told me. They specialized in churning out missives to DHS that requested information about individual immigrants so detailed, they sometimes seemed intent purely on overwhelming the system. One letter signed by Grassley, Sessions, and their Senate colleague Michael Lee asked DHS to respond “in precise detail” to queries about 250,000 immigrants.

Aside from Miller, perhaps the most important architect of Trump’s immigration policy is another young Sessions acolyte, Gene Hamilton. In 2008, while he was a law student at Washington and Lee University, Hamilton took an internship at an ice detention facility in Miami. In 2012, he scored a job as an ice lawyer in the Atlanta field office. (Back then, Atlanta was known as one of the most aggressive cities when it came to immigration enforcement: The court there granted asylum to just 2 percent of the seekers whose cases it heard. The national average is about 50 percent.)

At the beginning of the Trump presidency, Hamilton joined DHS as a senior counselor to then-Secretary John Kelly. Last year, he left DHS to serve as a top adviser to Attorney General Jeff Sessions. The logic of the job switch was made apparent to me by one former ice official, who described Sessions as the “de facto secretary of homeland security,” given his comprehensive influence over immigration policy. Together, Sessions and Hamilton have instituted a highly insular, fast-moving enforcement operation.

The work undertaken by Sessions, Hamilton, Miller, and their ilk is based to some degree on a theory first developed by Kris Kobach, the Kansas secretary of state. Over the past year, Kobach has emerged as a prime bête noire of the left because of his ferocious, ultimately doomed attempts to stamp out a phantom epidemic of voter fraud. But for many years, he served as a lawyer for an offshoot of the Federation for American Immigration Reform—the loudest and most effective of the groups pressing for restrictive immigration laws. In that position, he helped write many of the most draconian pieces of state-level immigration legislation to wend their way into law, including Arizona’s S.B. 1070.

Kobach set out to remake immigration law to conform to a doctrine he called self-deportation or, more clinically, attrition through enforcement—a policy that experienced a vogue in 2012, when Mitt Romney, campaigning for president, briefly claimed the position as his own. The doctrine holds that the government doesn’t have the resources to round up and remove the 11 million undocumented immigrants in the nation, but it can create circumstances unpleasant enough to encourage them to exit on their own. As Kobach once wrote, “Illegal aliens are rational decision makers. If the risks of detention or involuntary removal go up, and the probability of being able to obtain unauthorized employment goes down, then at some point, the only rational decision is to return home.” Through deprivation and fear, the government can essentially drive undocumented immigrants out of the country.

Once you understand that self-deportation is the administration’s guiding theory, you can see why immigration hawks might take satisfaction in supposed policy defeats. Even if putative fiascoes such as the initial Muslim ban and family separations at the border fail in court or are ultimately reversed, they succeed in fomenting an atmosphere of fear and worry among immigrants. The theatrics are, in effect, the policy.

The Trump administration made explicit its policy that every undocumented immigrant is unsafe with the executive order that Trump signed during his first month as president, repealing Obama’s policy of prioritizing the deportation of immigrants who had committed serious crimes. As Thomas Homan testified before Congress last year, “If you’re in this country illegally and you committed a crime by entering this country, you should be uncomfortable … You should look over your shoulder, and you need to be worried.”

The administration has attempted to encode the spirit of that warning across the spectrum of immigration enforcement. For years, such enforcement has abided by a policy intended to give undocumented immigrants a sense of safety in “sensitive locations.” ice has, for instance, refrained from apprehending immigrants at schools, places of worship, and hospitals. The theory is that even if an immigrant might be at risk for deportation, she shouldn’t think twice about, say, visiting a doctor. But anecdotal evidence suggests that ice has been operating more often in the vicinity of sensitive locations: Agents arrested a father after he dropped off his daughter at school, and detained a group soon after it left a church shelter. ice has also attempted to undermine so-called sanctuary cities, which decline to hand over undocumented immigrants whom their police happen to arrest. ice has loudly trumpeted its escalation of raids in those cities, sending the message that any notion of sanctuary is pure illusion.

To date, there is little evidence that self-deportation is occurring in any meaningful numbers. Ample data, however, show that increased fear has caused immigrant families to alter their life routines. One study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that undocumented immigrants tried to limit their driving in order to lower the chance of an inadvertent interaction with the police. Many immigrant parents now keep their kids indoors as much as they can. One woman told Kaiser she noticed that once-vibrant playgrounds in her neighborhood were suddenly vacant.

Likewise, police departments around the country have noted a sharp decrease among Latinos reporting domestic violence and abuse. (In Los Angeles, for instance, reports by Latinos of sexual assault dropped by 25 percent in the first four months of 2017 compared with the same period in 2016.) Women would apparently rather tolerate battery than expose their partner to the risk of deportation—or risk deportation themselves. According to the Houston Chronicle, waiting rooms at many health clinics serving undocumented immigrants in South Texas are half as full now as they were before Trump took office. And schools in suburban Atlanta report that immigrant parents are reluctant to sign their kids up for reduced-price lunch programs.

Researchers from UCLA interviewed teachers and counselors at schools across 12 states to gauge the impact of zero-tolerance immigration policies in the classroom. They found that children of undocumented immigrants consistently expressed fear at the prospect of returning home from school only to find their parents and siblings gone. An art teacher reported that “many students drew and colored images of their parents and themselves being separated, or about people stalking/hunting their family.”

Fears of ice can be exaggerated by word of mouth or compounded by hyperbolic news reports, especially in the Spanish-language media. But the activists who interact most frequently with ice, who pay daily visits to detention centers and immigration courts, share immigrants’ sense of trepidation. This spring, an immigration lawyer from Santa Fe named Allegra Love went to Mexico to visit a caravan of Central Americans headed to the California border. By the time she arrived, the procession, organized by the activist group Pueblo Sin Fronteras, or “People Without Borders,” had swollen to hundreds of asylum seekers and attracted the attention of the media, especially Fox News. President Trump described the caravan as a “disgrace.” Although Love has made a career of advocating on behalf of immigrants, she had come to Mexico with an explicit message of discouragement. “I wanted to keep these people safe and needed to explain to them how willing our government is to make them suffer,” she told me. She conducted a workshop in a makeshift refugee camp in the city of Puebla. As hundreds of migrants gathered, she addressed them with a microphone: “The system has become so appalling. You need to be afraid. You need to take that into account.” For the first time in her life, she was actively attempting to deter people from seeking refuge in the United States. This is the terrible irony of Trump’s policy: It turns even devoted activists into unwitting servants of its goals.

Donald Trump talks a lot about the crisis at the border. But over the past generation, the U.S. has spent tens of billions of dollars sealing the frontier with Mexico. It has invested vast sums in surveillance, fencing, drones, agents. A generation ago, politicians bemoaned the influx of Mexicans into the country. Ten years ago, Mark Krikorian, one of the most prominent conservative theorists on the subject, wrote a highly touted book warning about Mexican plans for a reconquista: Through mass migration, he argued, Mexico would attempt to erode American sovereignty and exert influence over the United States. Yet just as he promulgated that argument, the problem he diagnosed was disappearing. The nation’s rigid security has made casually traversing the border much harder. In recent years, there has often been more migration to Mexico than from Mexico. The Pew Research Center has estimated that there were 1.3 million fewer undocumented Mexican immigrants in the United States in 2016 than in 2007. Even with the recent surge of Central Americans fleeing violence in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, illegal border crossings are a fraction of what they were in the 1980s and ’90s. In 2000, the U.S. apprehended 1.7 million people crossing the southwest border; last year, it nabbed just over 300,000. Contrary to widespread belief—and the president’s frequent complaints—very few borders have the dense, protective security layers present on America’s border with Mexico.

But even as the nation solves one problem, politicians and bureaucracies concoct new ones. Border Patrol has started aggressively taking advantage of an old regulation, long ignored, that permits an expansive definition of border, encompassing all terrain within 100 miles of the physical frontier. It has leveraged this flexible interpretation to set up checkpoints along I-95 in Maine and to board buses in Florida to ask passengers about their immigration status. Border Patrol has become a regular presence in cities such as Las Vegas and San Antonio—and its officers can be seen cruising highways in northern Ohio.

A similar mission creep afflicts ice. It’s hard to argue with the need for a bureau that can deport criminals who reside in the country illegally. But there are only so many of them. Study after study has shown that immigrants commit crimes at much lower rates than the native-born population. ice simply doesn’t have enough criminal targets to justify its enormous budget. That’s why, when Obama provided ice with strict priorities, its number of detentions quickly plummeted.

“Abolish ice” is a slogan, now fashionable among Democrats, that has a radical edge. Prudent policy, however, requires not smashing the system, but returning it to a not-so-distant past. Only five years ago, the political center deemed the legalization of the country’s 11 million undocumented immigrants a sensible element of a broad compromise. Only 15 years ago, before the birth of ice, America had a bureaucracy that didn’t treat them as a policing problem. Immigration enforcement was housed in an agency devoted to both deportation and naturalization. There’s no reason to wax nostalgic for INS, which had plenty of problems of its own. But the U.S. can now borrow from its positive example and design an institutional structure that restores a sense of proportion to the limited dangers posed by the immigrants embedded in American communities.

Lacking a large number of worthy targets, ice will train more of its attention on the likes of Jack, an undocumented immigrant from Mauritania whom I met this spring. (Jack is not his real name, but he does go by an Americanized nickname.) As Jack drove me around Columbus in his aging but meticulously maintained sedan, I came to think of him as an evangelist. With his round face, shaved pate, and impressive mustache, he exuded an optimism so cheery that it can only be described as faithful. I found myself disappearing into his homilies, as he set out to convert me to his version of the American dream.

As we meandered past Refugee Road toward his neighborhood, he wanted me to know that he had had the vision to buy a model home at a good price long before the developer had filled out his street. When we arrived at his place, he asked me to gaze out upon his little village of cookie-cutter houses and winding asphalt. The morning’s drizzle had turned to mist, and Jack closed his eyes and theatrically inhaled, an expression of self-satisfaction like one might see in a TV commercial.

He took me inside through his garage, past a shelving unit filled with four tiers of sneakers. Jack, a farmer’s son, takes huge—and very American—pleasure in abundance. Nearly every room in his house seemed to have a television set tuned to CNN. I saw pictures of his young son—born in Columbus, and a U.S. citizen—as well as an image of the former Ohio State University football coach Jim Tressel, whom Jack once met at a parade. I followed him to his basement, which he is in the early phases of transforming into a shrine to the team. The walls will be painted in the school’s colors, scarlet and gray. “It will be my man cave,” he told me.

Jack then led me up to his office, which has his favorite view in the house. It looks down on his deck and grill, across a grassy expanse of yard. Jack, who is in his mid-40s but looks older, is a professional mover. He works for a big company that specializes in long-distance relocations. At the beginning of the Trump administration, Jack even packed up the home of a soon-to-be senior Cabinet member and hauled his belongings to Washington. On the shelf opposite his desk, he keeps the awards he’s collected from his company for the excellence of his work.

“I refuse to give all this up,” he said. An officer at ice, whom he considers especially kind, has told him that it’s only a matter of time before he is detained and deported. But Jack, ever the American optimist, believes there’s no problem that can’t be solved. “I will tell them that I know I did the wrong thing. I came here without papers. But look at me. I’ve never broken a law. Fine, deport the guys who have committed a crime. I will say, ‘Look. It’s me, Jack.’ I will joke with them and let them know I’m not a threat. When I talk to them reasonably, they will relax.” Even with the threat of deportation hanging over him, he has disciplined himself to keep on believing. A few days earlier, he had bought a truck to start his own hauling company. “I want to employ people, to give them opportunities like I had.”

As we went through his office, he became wistful. He opened his closet and showed me the suit he had worn on his flight to America as a young man, almost 20 years ago. He had me run my hands along its frayed lapel. Then he grabbed a leather-bound notebook sitting on his printer and opened it. “Here are things that my girlfriend will need to know.” He had written instructions on how to access his bank accounts, open his safe, sell his house, reach his son. As he showed this to me, he finally broke from his customarily cheery character and said nothing. He closed the book and traced the cover with his finger one last time. Then he looked at me and said, “When the day comes.”

This article appears in the September 2018 print edition with the headline “How ICE Went Rogue.”