Perfectly on time, Scooter Braun strides into a small, windowless room at Cannes’ Midem convention, the annual gathering of the world’s music business. For someone who has just flown in from the US, he looks remarkably good: suit and shirt perfect, no hint of jet lag. But these are good times, even by Braun’s standards. The man who once sold fake IDs at university could now reasonably claim to be the biggest manager in pop, with a personal fortune estimated at $23m (£17m), thanks to his involvement with the likes of Ariana Grande, Justin Bieber and Carly Rae Jepsen, as well as canny investments in Spotify, Uber and Dropbox. He has just announced the first film to come out of his studio, Mythos – an animated movie called Cupid, with Justin Bieber voicing the title character – and the founding of a reality TV company, GoodStory Entertainment.

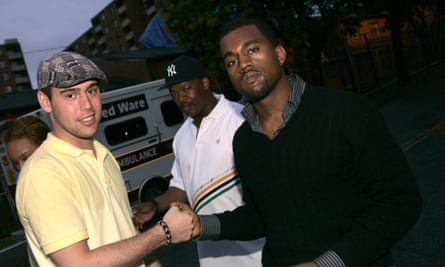

His relationship with his most wayward artist, Kanye West, is back on, after a “rough” couple of weeks in which West fired him, apparently enraged at Braun’s refusal to get rid of all his other clients and work solely with him. West announced that he couldn’t be managed (Braun favourited the tweet) in a media rampage that also included doubling down on his support for Donald Trump and appearing on TMZ to suggest that slavery was “a choice”. A “manic moment”, suggests Braun, brought on by the rapper’s bipolar disorder.

West subsequently “called me up and said: ‘We’ve had a great thing for the last couple of years. And [in] the last two weeks, I think, a lot of things have got out of hand, and we’re brothers – come help.’ I really do love the guy. We’ll see how long it lasts, but I’ll always be a friend to him. We’re not going to use the word ‘manager’ – it’s not a word that he likes, nor does it really describe our relationship. I see myself as an adviser and a partner in his efforts.”

But, as a manager, Braun’s stock is more buoyant than ever, in part because he has shown a remarkable capacity for turning tragedy into triumph, such as after the terrorist bombing at Grande’s Manchester Arena gig last year. His reaction was initially prompted, he admits, by anger. “I wanted to fight back. My grandparents are Holocaust survivors, so I have known that kind of evil exists my whole life. I’ve been waiting for it to come my way [for] my whole life, and my initial reaction was: ‘You’ve fucked with the wrong person.’” He arranged for Grande to see a therapist and pulled together the star-studded One Love Manchester benefit concert in 12 days, calling in favours from everyone from Chris Martin to the footballer Robbie Keane.

Then there was the saga of Bieber’s 2013-14 fall from grace, a classic teen-idol-gone-wild scenario involving rumours of problems with alcohol and prescription drugs and a string of arrests for vandalism, driving offences and assault. It should have been the stuff of career-ending disaster. Instead, here Bieber is, clean, sober and a bigger star than ever, thanks not just to the exceptionally well-made 2015 album, Purpose, but also to a public rehabilitation that Braun says he began planning the moment Bieber “looked me in the eye and said: ‘I’m making a change.’”

Braun won’t be drawn on what went wrong in the first place, other than to say that he thought Bieber might die. “I was not going to give up on him, I was not going to let him die, I was not going to put him in that position of: ‘Oh, let’s just keep him working.’”

He says he isn’t worried that Bieber’s recent born-again Christianity may affect his popularity. Bieber was baptised – in the bathtub of a New York Knicks player, no less – by Carl Lentz, a pastor from Hillsong, a Pentecostal “megachurch” that has attracted criticism for its views on homosexuality. “At the end of the day, I would choose this result over what I was dealing with, a thousand times over,” says Braun. He thinks for a moment. “The best thing that happened to Justin Bieber is that he found God. He was able to remove himself from being worshipped, and realise he’s in service to others. Because I don’t think human beings are built to be worshipped.”

Throughout it all, Braun has maintained a remarkably high profile for a pop manager. If he is scrupulously deferential to his clients in interviews – insisting it is Bieber who deserves credit for turning his own fortunes around, and that Braun only gave a speech from the stage at One Love Manchester because Grande didn’t want to do it herself – he is nevertheless very visible. He has more than 4 million Twitter followers tuning into a stream of plugs for his artists, photos of his family and self-help homilies. Rather than denying that he seeks the limelight, he says it was part of the plan from the start, devised when he was still a student.

A well-raised Jewish boy from a nice part of Connecticut, he faced down antisemitism at school – someone carved a swastika into his car when he was elected class president – and went to study in Atlanta, promoting hip-hop parties as a sideline. One year, he says, Puff Daddy co-hosted a party with the manager of Outkast, then the world’s biggest hip-hop act. The next year, Outkast had split, their manager was no longer their manager, and Puffy was hosting a party without him. It was a cautionary tale never to make Braun’s success dependent on someone else, although he knew that building his own brand would be divisive. He never aspired to be a manager, he says, and, at 37, admits that he will be annoyed if he’s still at it in his 50s. “I love working with the people I work with,” he says. “I’m blessed to be a part of these people’s stories. But their story is not just going to define mine.”

There are frequent suggestions that he might enter politics. Last year, it was reported that the Democrats had approached him about running for governor of California. He was, he says, “getting pressured to do so at certain points”, but thinks he would be better off “doing good work in the private sector”. As well as One Love Manchester, he worked behind the scenes helping to organise the post-Parkland shooting March for Our Lives. “I think I still have unfinished business on the business side of my life,” he says. “If I were to go into a public-office position, I would want to remove myself completely from the business world.”

Still, he thinks management may have primed him for politics. “In politics, you’re representing your constituency, and you have to listen to opinions that you might find to be irrational. And, in doing my job as [a] manager, I have learned how to humble myself to have conversations with people who I at times find irrational, and come to common ground or get them to see the light, or hear what they’re saying. Management has taught me that if you don’t like something, you don’t strike it down: you respect it, and you have a conversation with that person.”

He would be very convincing on television. When you ask him a question, he thinks for a moment, then the answer emerges, perfectly articulated, without an “um” or an “er” to be heard. He doesn’t appear to be much plagued by self-doubt, although he does keep bringing up the fact that he is nearly 38 as though looming middle age might blunt his self-proclaimed ability to identify a gap in the market and find an artist to fill it. “Am I going to tell you what I think the gaps in the market are today?” he asks, incredulous, when I mention it. “No, because I don’t want competition.”

He has, it is true, repeatedly turned out to be absolutely right when everyone else suggested he was wrong. He graduated from promoting parties to working for Jermaine Dupri’s So So Def label, but left after a few years because, in part, he says, no one would listen to him telling them that social media was the future. “People thought I was crazy,” he nods. “I had ideas of using YouTube to break an artist by making video content, and everyone said: ‘You can’t take an artist off YouTube and make them into a star – this lo-fi content is not how you break an artist.’ When I first started saying artists should tweet at fans and follow fans on Twitter, people were like: ‘Why would you do that?’”

He claims that the moment he clapped eyes on Bieber – on YouTube – he knew exactly how to make him the biggest star in the world. “I don’t even think it came from me. I’m a person who believes in God,” says Braun. But no one else believed him. “I took Justin from 60,000 views to 66m. An independent artist who was No 2 on YouTube in the world: no one would sign him. No one.”

He says that “doubt and disrespect” drive him. Certainly, he seems to have a photographic memory for everyone who has ever slighted him, from a kid at school who disrespected his father to a basketball coach who is now in jail; from Piers Morgan (who accused Grande of “running away” when she returned to Florida after the Manchester bombing) to rock manager Peter Mensch, who announced that Bieber’s drink-and drug travails didn’t matter because “no one’s going to remember his name in three years anyway”. “And that was four years ago,” he says, in dish-best-served-cold style. “Or five, I believe, at this point.”

He has to go to another interview, this time on stage: he is Midem’s big star booking, the first recipient of its hall of fame award. The audience greets him like a conquering hero. He tells them that “anyone who says they make their own luck is an asshole” and that Kanye West “doesn’t have a malicious bone in his body”. He had told me exactly the same thing earlier: what a great guy he is in person, how much he cares about people, how those who make fun of him are mocking someone dealing with mental health issues. “There are things he has said that I vehemently disagree with. Do I let him off the hook? No, I have conversations and I try to push the points of where I am, and I wish the world could get to hear what he’s saying in those private conversations because I think it would explain a lot and also clarify what he really meant. But, y’know,” he shrugs, “he’s Kanye.”

Wouldn’t your best advice be for him to just keep off social media? There’s a pause and, for once, an “um”. “Yeah. I mean, look, if you’re in a good place, yeah, go on social media.” And then, like the politician he may become, Braun neatly changes the subject. “But I’d also say I’m more concerned with the president of the United States being on social media than I am with Kanye West.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion