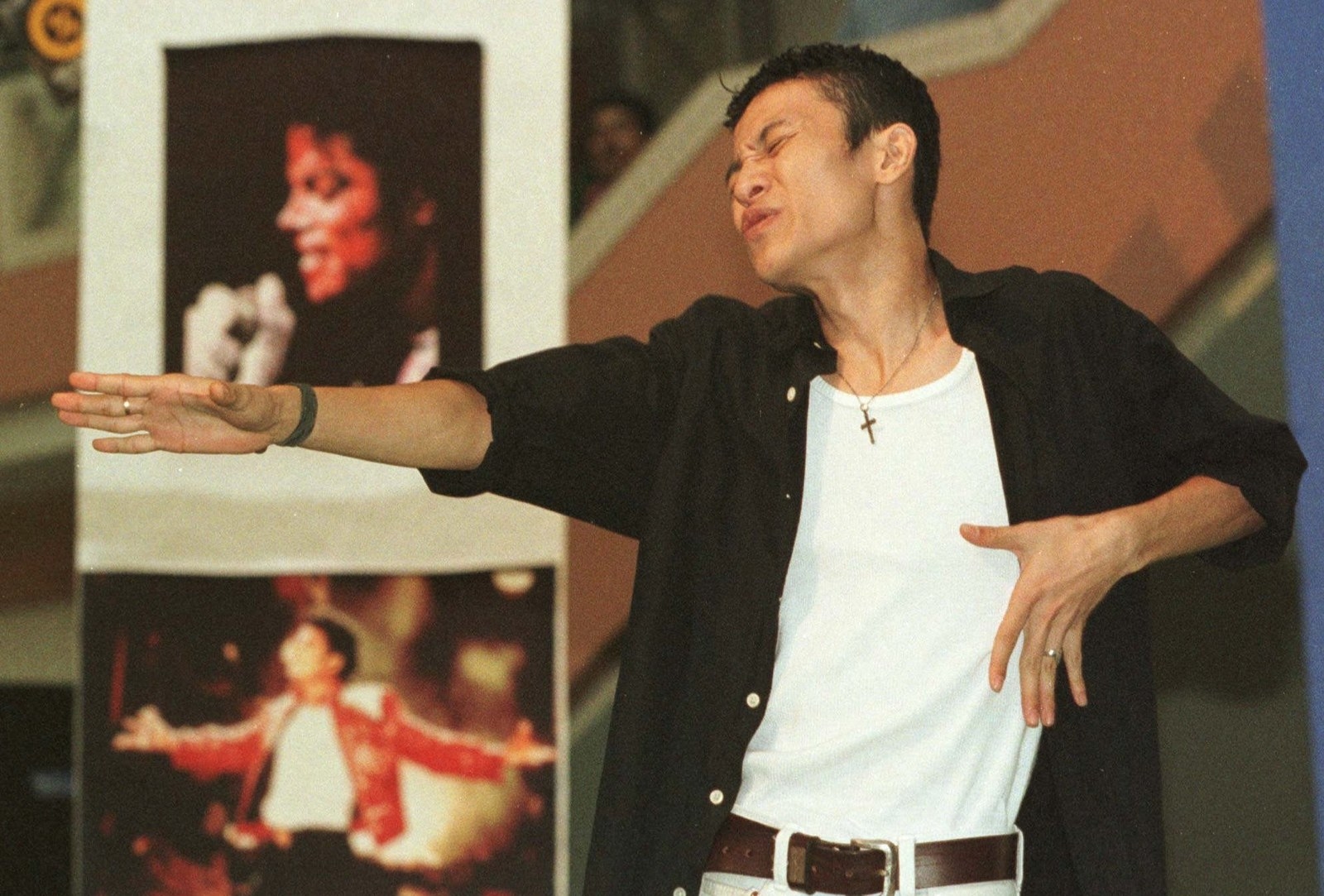

When Michael Jackson came to Malaysia in October 1996, fans mobbed the old Subang International Airport and ran after his motorcade; little boys and grown men emulated his moves at shopping mall talent shows; and grandmothers stood in line for hours outside the concert venue for front-row seats to history. The nation’s four television stations faithfully reported his whereabouts on the nightly news: Here’s Michael signing autographs on his way to Toys ‘R’ Us; here’s Michael getting sprayed with Silly String by kids from a children’s home; here’s Michael waving from the balcony of his 18th-floor suite at the Hilton while streams of multicolored balloons ascend through the hundred feet of air separating him from his giddy, starstruck congregation. Throughout, Michael appeared to endure the meteorological seesaw from 95-degree tropical heat to arctic indoor air-conditioning with equanimity, rarely shedding his heavy artillery coat, aviators, or delicately embroidered black-and-gold surgical mask.

My parents and I must have just finished dinner when one of the TV stations broadcast highlights from his concert the night before. My father had retired to the living room to watch the news, my mother outside to the kitchen, while I lingered on the staircase between the living room and the study, hoping to catch a glimpse of the spectacle. (My sister was away at university.) I saw faces, partially lit, telegraphing anticipation. A spotlight illuminating his lone figure atop a crane. His iconic roar and subsequent descent into 55,000 ecstatic fans at Stadium Merdeka, where, 39 years earlier, Malaysia’s first prime minister declared independence from a century of British colonial rule. My 13-year-old self felt a swell of kindred feeling, watching fellow Malaysians of various shades and walks of life jumping, swaying, screaming, and attempting the moonwalk together, as they witnessed what they might remember, years later, as the performance of a lifetime. Even my mother, a schoolteacher and vehement critic of what she called “the idiot box,” emerged from the kitchen to watch. “Well,” she said in Cantonese after a few minutes of quietly taking it all in, “I don’t know if any other artist will be as mourned by the world when he dies.”

I remembered my mother’s rumination many years later, after I had moved to the United States for college and stayed for work. It was June 2009. I was briefly living in New York City. While visiting a friend at his design studio in Soho — where the windows had been thrown wide open to let in a balmy, late afternoon, and the whine of wheels in stop-and-go traffic punctuated our conversation — my eyes picked out the breaking headline on his computer screen. I scanned it again for confirmation and read it out loud to my friend, who looked at me from across the room in disorientation, then disbelief. Are you sure? As if on cue, in impromptu homage, somewhere outside, a man in a convertible turned up his car stereo to the opening bass line of “Billie Jean.”

As a teenager, I got to know Michael’s songs mostly by osmosis. A friend fed his body of work into the cassette tape deck on the bus that took us to and from school every day. Our hourlong morning bus route would begin in the suburbs amid old bungalows and terraced houses ringed by second-growth rainforest, and take us past the old Moorish Revival railway station, the national mosque, and the Sultan Abdul Samad Building; past brick shophouses and the Sikh uncle with the orange beard who sat guard outside a nondescript establishment where textiles and gold jewelry were sold; past glass-and-steel office buildings and concrete high-rise flats tinted gray by smog, before arriving at a colony of shopping malls and five-star hotels, amid which our public all-girls secondary school, founded by Scottish missionaries in 1893, improbably withstood the surrounding tumult of commerce and tourism. On this commute we would journey through old, danceable Michael (“Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’”); fractured, new Michael (“Scream”); sweet, melancholic Michael (“Childhood”); and strident Michael (“They Don’t Care About Us”).

Later, this friend — a consummate Michael fan, graced with a singular sense of humor and generosity — recruited a group of us as backup dancers for a talent show reenactment of the music video for Michael’s 1991 hit “Black or White.” I happily went along, welcoming an excuse to swap out our school uniform of pinafores and six-piece skirts for baggy track bottoms and a cap turned backward, what I thought then to be an edgy, androgynous look that was ultimately more young Macaulay Culkin — who appeared in the music video — than the King of Pop himself.

In the actual “Black or White” video, Michael jumps from one cultural and geographical context to another in dance. In one frame, he accompanies an Indian odissi dancer on a median, surrounded by traffic and signs of industrial progress; in the next, he’s doing high kicks among Cossack dancers in front of a mockup of Saint Basil’s Cathedral. The video reads like a promotional ad for globalization — continents are but a jeté away, local cultures and traditions are celebrated, no one is debating the virtues or perils of immigration or the loss of jobs to China. The music video ends with a mesmerizing minutelong face-morphing sequence, in which a stocky Chinese man transforms into a svelte African American woman, who springs curls to become a Caucasian redhead, who grows a goatee to become a dreadlocked man from the West Indies, who shapeshifts into a ponytailed woman of South Asian descent, and so on.

Michael Jackson, "Black or White"

View this video on YouTube

This vision of multicultural equality, that we are all one and the same despite our purported outer appearances, had special resonance among his Malaysian fans. Demographically, Malaysia is 61.7% ethnic Malay and indigenous peoples, 20.8% Chinese, 6.2% Indian, 11.3% a mix of “other” and noncitizens. Our racial plurality is a source of both national pride — as demonstrated in the country’s tourism ads — and complicated identity politics. In school, my friends and I learned how, from the late 1800s, Chinese and Indian communities crossed the seas as imported migrant labor, to work the tin mines and rubber estates and jumpstart local commerce in British Malaya. We learned how ethnic Malay communities in kampungs continued to labor in the fields and fisheries while the British cannily placed aristocratic Malay elites in administrative positions. We were taught that our founding as an independent nation in 1957 was contingent on these three primary ethnic groups — the ethnic Malays, Chinese, and Indians — transcending a hundred years of British colonial “divide and rule” and committing to peaceful cooperative governance. In my memory of the narratives in our history textbooks, there was little editorializing about how challenging postcolonial nation-building must have been, or how in the decade after independence, Chinese and Indian minorities were still regarded by the nativists within ethnic Malay communities as pendatang, a pejorative that simultaneously connoted newcomer and interloper. Uneven economic progress between the three racial groups bred resentment and tension, escalating into violent race riots in 1969 in which houses were burnt, shops were looted, and hundreds across both sides of the divide were killed. The country was placed under a state of national emergency for two years.

As children, my friends and I were unaware of these historical antagonisms. As young adults, some of us learned from our parents to distrust politicians who brandished the national trauma of the 1969 riots as justification for maintaining race-based policies. These policies included quotas which favored the ethnic majority (a critical difference from affirmative action policies in countries like the US) in matters ranging from academic scholarships and university admissions to business loans and government contracts. More often than not, they pandered to vote-garnering populism and disproportionately benefited the politically connected, rather than serve their original purpose of rectifying historical economic inequality. To publicly question or critically discuss the political motivations behind these quotas, especially as an ethnic minority, is to contend with the threat of arrest and imprisonment under the Sedition Act, a holdover from British colonial rule.

And yet, the Malaysia of my childhood — my subjective, imperfect memory of it — is unequivocally joyful. That I was insulated from the effects of racialized policies I attribute to parental love and luck, as well as idealism, because I was part of a generation of Malaysians raised during a period of optimism and general economic prosperity. My family was comfortably middle class, though one generation removed from the kind of poverty that I glimpsed through childhood stories that my mother infrequently told, like the one in which she and her four siblings had only potatoes dipped in soy sauce for dinner. I went to an urban public school that prided itself on academic excellence and was surrounded by talented peers whose backgrounds cut across race and social class. The few brushes I had with structural inequity seemed fleeting and inconsequential, like the time a teacher revealed that I had been assigned the role of deputy head at my primary school’s prefectorial board because the school administration deemed it necessary, for optics, that a Malay student assume the role of head prefect instead. I didn’t begrudge the decision as much as I found the rationale astonishing — as far as I was concerned, my compatriot was equally qualified for the position.

Our racial plurality is a source of both national pride — as demonstrated in the country’s tourism ads — and complicated identity politics.

My parents, extrapolating to the future and perhaps knowing better, never once allowed me to forget that old chestnut — that in my academic and intellectual endeavors I needed to be, as my mother put it, “heads and shoulders better than everyone else.” To her, the pursuit of exceptionalism did double duty: It uncovered options and opportunities for a full life and rendered inequity visible. She and my father saved relentlessly so that they could send me and my sister to universities abroad, where we might have the possibility of having futures without the calcified complications of race in Malaysian political culture.

“What is peculiar, even a little bitter, about living for so many years away from the country of my birth,” writes English critic James Wood about his own immigration to the US, “is the slow revelation that I made a large choice a long time ago that did not resemble a large choice at the time.” The choice I made at 18, which did not feel large or life-diverting then, was to accept a scholarship for undergraduate study in the US. In a stroke of ironic luck, after I graduated from secondary school, the Malaysian government awarded hundreds of scholarships for university study at home and abroad purely on the basis of merit. In 2002, I, along with friends with whom I had shared seats and desks in classrooms for years, began to scatter across the globe to universities in Malaysia, France, Germany, India, Ukraine, the US, the UK, and Australia. What once felt like a single stream of parallel life trajectories now began to branch and fork into dozens of tributaries, the odds of each tributary intersecting with another diminishing with time.

There is usually a point during a conversation among those similarly displaced from their places of birth when one asks the other that inevitable question: Do you think you will ever go home? Posed in the spirit of genuine curiosity, the question, often freighted with both hope and elegy, also gives the asker herself an opportunity to turn it over anew with a different interlocutor. For a while, the answer when I was a college student and later a newly minted tech industry professional was I’d love to or Maybe in a few years. It was often complicated by snippets of news from home: instances of qualified minority students being rejected from scholarships and local universities; politicians roundly dismissing a 2011 World Bank report, which cited “economic conditions” and “social injustice” as chief factors for Malaysia’s brain drain; the spectacle of activists and journalists being hauled into court or solitary confinement; and stories of corruption in what had been the ruling party before an unprecedented election this past May. I would feel homesick for family, the food, and that banal, day-to-day luxury of being seen and understood, at least on the surface. At the same time, with every passing year over the past decade and a half, I’ve gradually built a life, a career, and a community of people I love in the US, and let free the parts of myself that have only been able to find full expression in my adopted country.

Around the time that the music video for “Black or White” was released in 1991, Malaysians christened soya cincau, a popular local drink sold at roadside stalls and restaurants, with a new moniker: the “Michael Jackson.” The drink is a slurry of black grass jelly suspended in chilled soy milk: a visual intermingling of black and white, turning a milky brown where the two meet. If you look up “Michael Jackson drink” online, you will find several articles attributing the name’s origins to the popularity of Michael’s hit song. But I’ve always suspected a less charitable subtext: We were also commenting on Michael’s physical transformation, his skin becoming lighter and his face more aquiline as his career progressed from Thriller to Bad to Dangerous. “For some,” writes cultural theorist Nicole R. Fleetwood in Coda: The Icon Is Dead: Mourning Michael Jackson, “Jackson’s physical transformation is evidence of an obsessive desire and hopeless failure to embody whiteness.” Although Fleetwood’s observation is made from within the American milieu, the sentiment travels across borders. If the inventors of Malaysian vernacular at that time were throwing shade at Michael, it was performed with an awareness of shared complicity in a culture that made space for skin-whitening creams and a tendency to be obsequious toward white-presenting tourists.

I was ignorant of American race dynamics and the continuing history of violence against the black body.

When I listen to “Black or White” now as an adult living in the US, I realize that, having grasped the song as a teenager only through its images of global multiculturalism, I had missed a vital thread in its lyrics. I sang along but didn’t fully comprehend lines like I ain’t scared of no sheets or I’m not going to spend my life being a color. I was ignorant of American race dynamics and the continuing history of violence against the black body. What I knew then of American history was gleaned from a Malaysian history-textbook romp through the Declaration of Independence to the Civil War to the US’s involvement in global wars, skipping the vicissitudes of Jim Crow and the civil rights movement, save for a brief mention of the assassination of a man named Martin Luther King Jr. This exclusion implied that the history of black-and-white entanglement in the US was a provincial matter, as though there was nothing at all existentially urgent about understanding how or why the most powerful nation in the world systematically oppressed an entire people.

In the essay I Is Another, Valeria Luiselli recalls an early encounter with the American question of race. Sitting in the waiting room of St. Luke’s Hospital shortly after she moved to New York, a feverish Luiselli worked through a medical questionnaire that she had been given. “I hesitated in front of the question for a while,” writes Luiselli, “traveling up and down the ladder of choices with the tip of my pencil: White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, Other.” The scene depicts a moment of relocation that is familiar to one who has moved to another country as an adult: where am I, how do people here see themselves, and who am I in their construction of the world? If those considerations weren’t dizzying enough, one might begin to imagine centuries of geopolitical events, cultural exchange and appropriation, violence, diplomacy, hope, and displacement all flattened into an ahistorical and deceptively straightforward multiple-choice question.

In the beginning, I was, very simply, an international student and Malaysian. The former was administratively useful for visa paperwork as a college student, the latter sufficiently meaningful to me, and the classmates and cab drivers I encountered who were curious about my provenance. In a new country, I felt liberated from racial categories that I previously knew, and whatever the American conception of race was seemed irrelevant in the protected bubble of college in the San Francisco Bay Area, where I studied engineering and met students from literally everywhere. Asian as a category felt ludicrously monolithic and abstract, and Asian American plainly didn’t apply because I wasn’t American. (My experience at the airport’s immigration threshold served as a constant reminder of the latter fact — instructions to snaking queues of tired travelers were sometimes barked and bodies roughly herded; on customs forms, all of us reentering the US after winter break were referred to as alien.)

I don't remember exactly when the ladder of racial categories started becoming less conceptual. It might have been when I became, after many years, a permanent resident of my adopted country and attempted to call two countries home. It might have been when the tech company where I worked first released its diversity numbers and I began to see the glaring absences when I looked up and around me. It might have been when Trayvon Martin was killed and when the killings kept happening in Ferguson, Charleston, Charlottesville, in too many towns to count; when every day on social media in Trumpian America announces some fresh aggression meted out on a black or brown citizen, an immigrant, a parent, families, or young children incarcerated in detention centers. My education in these aspects of the US came gradually and late, a privilege that now seems inconceivable to me.

It’s sometimes difficult to know how to best be in the presence of this knowledge. Several months ago, standing around a table of food at an event and chatting with a dear college friend and a professor I respected and hadn’t seen in years, the topic of conversation turned to the state of the internet and its mess of clickbait, polarization, and outrage. The professor asked whether, given a time machine, my friend and I would choose to live in the present, the past, or the future. I understood what the professor was getting at — it was a question about the extent to which we were nostalgic for a past before the current runaway technological train, or conversely, optimistic about a future of techno-utopian possibility. But maybe because I had recently listened to writer Zadie Smith on an episode of Fresh Air talking about historical nostalgia and its availability to only certain kinds of people, or maybe because the professor was white and my friend was black, I found myself taking the conversation off the rails, parroting a version of what I thought Zadie had said: that I could not think of a period of time in the past when it might have been a good idea to be both a woman and a person of color. The professor gave me a long look, thrust an arm forward and positioned it next to mine, remarking in a tone at once lighthearted and conciliatory that we were surely close enough in skin color and therefore not that different from one another.

On May 9, an event of seismic significance happened in Malaysia, the kind that radically shifts conceptions of home for many across the Malaysian diaspora. For the first time since independence, an alliance of opposition parties, Pakatan Harapan, ousted the incumbent ruling party in a sweeping and unexpected electoral victory, effectively ending — at least for now — 61 years of single-party democracy marked by curtailed press freedoms, repeated gerrymandering, and most recently a $4.5 billion international corruption scandal. On Facebook there were tales of heroic attempts to get the overseas vote back to Malaysia literally by hand. But it was ultimately those at home, those who stayed, who turned the tide.

It was late morning where I was in New York City, and late at night in Malaysia, when the results started trickling in. My Facebook timeline and WhatsApp group chats with family and friends were populated with cautious expressions of hope, photos of index fingers dipped in indelible election ink, and of wizened makciks and pakciks waiting in the sweltering heat for their turn at the ballot box. As the opposition’s electoral count slowly ticked upward, district by district and state by state, equalling and then surpassing the incumbent, ultimately exceeding the parliamentary majority required to convene a new government, my social media feeds exploded with pronouncements of disbelief and joy. A few hours later, Malaysians everywhere were greeted with exclamations of “Salam Malaysia Baru!” — welcome to a new Malaysia.

Some of us watching from afar met the news with both elation and melancholy. “Not just because I was far away, unable to witness this moment I never thought I’d live to see,” reflects Preeta Samarasan, a Malaysian writer living in central France, “but for everything we had lost in these 61 years, each of us alone and all of us together.” What is lost, for Samarasan and those of us who have long chosen to painstakingly make a home elsewhere, is the opportunity to make our choices under a different set of circumstances. The point isn’t that we would have necessarily chosen to return, but rather, that the reasons which propelled us in one direction or another could have been something other than the feeling of alienation and exile.

In the music video for Michael’s 1987 hit “Bad,” an 18-minute short film directed by Martin Scorsese and written by Richard Price, Michael plays a teen named Darryl who returns home for winter break, traveling from a predominantly white private school to a predominantly black, unnamed inner city touched by urban blight. Onscreen, Darryl doesn’t completely fit into either context. The abbreviated version of this music video that most international audiences are familiar with centers just on its West Side Story–inspired song-and-dance sequence, filmed at New York City’s Hoyt–Schermerhorn station. The shots are tight and the dance choreography sublime, but what has always left the biggest impression on me is how, in attempting to depict the ways in which race and class can introduce disjunction into an individual arc of life, the full-length film also provokes a meditation on in-betweenness: Where is home? Is there only one? Who gets to lay claim to citizenship, and what is its price of admission? ●

CORRECTIONS

The Indian dancer in the "Black or White" music video is an odissi dancer not a bharata natya one. An earlier version of this article misstated the lyrics.