The title of Nine Inch Nails’ new tour, kicking off in Las Vegas’s Hard Rock Hotel & Casino, is Cold and Black and Infinite. To get here you must pass the tumbling dice, the restless women queuing for the Magic Mike live show, and the inert displays of Johnny Cash memorabilia. It is slightly incongruous, appearing as it does down the street from Backstreet Boys: Larger Than Life and Mariah Carey: The Butterfly Returns, but no less razzle-dazzle in its own way.

Since forming in 1988 as the brainchild of Trent Reznor, Nine Inch Nails have taken various anti-commercial elements – industrial noise, songs about pain, absence and sex – and hammered them into Vegas-ready shapes, showtunes for the goth-glam set. Thirty years on, Reznor – the only official member until 2016, when his long-term British collaborator Atticus Ross was added – is in one of his most fertile periods, having just completed a trilogy of releases with new album Bad Witch, six arresting tracks of wailing sax, acid house bass lines, and post-punk drumming, topped with Reznor’s trademark misanthropic lyrics (“I eat your loathing, hate and fear”).

“We’re just animals that, left to our own devices, will kill each other,” Reznor shrugs, his regulation all-black attire making him blend into a leather sofa backstage. “We’re only out for ourselves anyway. This illusion that we’re more than that is nothing but that: an illusion.”

This bleak worldview has barely changed since the band’s beginning. After his parents divorced, Reznor, now 53, was raised by his grandparents in Mercer, Pennsylvania, a “little, shitty town, a small-aspiration environment” between Cleveland and Pittsburgh, the kind that – in teen movies – only has room for one hooded, bullied outcast. “I was always good at math, and I was going to be an engineer, because you had to have a real job,” Reznor says. “Where I come from, there are no artists; artists were teaching at the high school down the street.”

Long before the internet and with no access to cool college radio, Reznor was immersed in mainstream AM-radio rock. “I could sing you every hit from the 70s, every word to every song, because I heard them all constantly. The idea of having a chorus and a melody, it’s beaten into my head.” At 23 and working alone under the influence of Prince, the industrial label Wax Trax! and more, he started writing the songs that would make up the band’s brilliant 1989 debut album Pretty Hate Machine: tinny, seething tracks that had definite shades of Depeche Mode, Nitzer Ebb and other twisted synthpop, but with a head-banging street-punk swagger that was totally new.

The lyrics conjured up a struggle between God, love and death as Reznor contemplated suicide, sin and salvation in sex. “I fucked around with some bad music; I was trying to sound like other bands,” he says of his pre-Pretty Hate material. “I thought the Clash were cool so I was trying to be cool, too. Important political statements, no one’s going to make fun of me for them. But the journal entries of a horny, sad guy who doesn’t fit in ...” He realised that the words he was writing in his journal – “to keep myself from going crazy” – were the real lyrics he needed, and Nine Inch Nails’ success was quick and exponential.

Today, with burly arms and designer stubble, he is still a rock star, but one with a top note of nerdish unease: shoulders ever so slightly tensed, head ever so slightly bowed. He says he has never fully grown out of the disquiet that powered Pretty Hate Machine and sent him into a gyre of self-destruction in the 1990s – The Downward Spiral, to quote the title of the band’s multi-platinum 1994 followup, infamously recorded in the house where the Manson family murdered Sharon Tate.

“The self-destruct button was pushed when I first started writing,” he says. “There was a sense that I couldn’t fit in anywhere, I couldn’t relate to people; I felt alone, I felt angry about it. And part of me is still that. I felt like I was heading down into something that wasn’t going to have a good ending. That ended up being addiction: its claws were in me but it hadn’t fully revealed itself.”

Reznor began drinking, then using hard drugs, culminating in an accidental heroin overdose in 2000 that nearly killed him. “I wasn’t the guy who aged 12 had a beer and turned into a werewolf,” he says. “It kind of crept up. I wasn’t prepared for the transformative effect of fame and recognition. Now everyone’s here to see me, and I still feel like I don’t belong there, that I don’t deserve to be there, that I don’t know how to act. I don’t know how much of that is learned, how much is experiential, how much is in my DNA, how much is in how I was raised. But I found myself uncomfortable in a scenario where everybody wants to be your friend. Having a drink or two was a tool. It did help, for a while, until it started to define who I was. In every scenario I had to drink, because that was me now.”

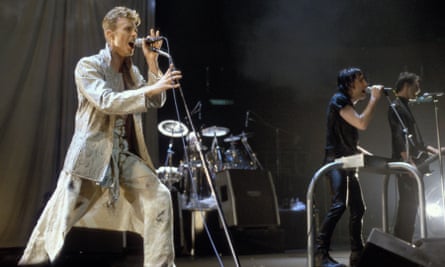

Someone who helped slow the rot was David Bowie, whom Reznor describes as his hero. He proposed a tour with Nine Inch Nails in 1995. “Things in my life at that time felt unrecognisable,” Reznor says, “and Bowie definitely helped. Not in a lecturing kind of way, but I saw someone who had come through [addiction], and he was happy and optimistic and remained fearless. I thought: if he can do that, maybe there’s light at the end of the tunnel.” Versions of Bowie’s I’m Afraid of Americans and I Can’t Give Everything Away feature in Nine Inch Nails’ tour setlist.

He also credits his wife Mariqueen Maandig, with whom he formed the band How to Destroy Angels and had four children, and Ross, the Eton-educated studio wizard with whom, outside of Nine Inch Nails, Reznor has scored a series of films and documentaries. They won an Oscar for their work on David Fincher’s The Social Network. “Over the last 18 years, we’ve probably spent more time together than we have with our wives,” Ross laughs, wreathed in biscuit-scented vape smoke when I meet him later on. “We work 11am to 7pm every day, and not on the weekend. Some people wait for inspiration. Our experience has been – and I’ve read this a lot about painters and writers I like, too – that it comes from the act of doing it, and continuing to do it.” Alongside the new Nine Inch Nails material, Reznor says the pair have been working on “two major things and two minor things”, neither of which he can disclose.

Reznor’s other recent extracurricular activity was working as chief creative officer for Beats Music – later bought by Apple – alongside the company’s co-founder Jimmy Iovine, who signed Nine Inch Nails to Interscope in the 90s (and who has since married Ross’s model sister Liberty). Reznor consulted on the streaming service that eventually became Apple Music. “I was trying to make the experience of how people listen to music feel more akin to walking into a great indie record shop rather than an FTP server,” he says. “There was always a part of me that wondered: what would it have been like if I went down the other branch of my life?” Namely, the one where he became an engineer in Mercer, Pennsylvania. “But I don’t want to do that, if I have the choice. It made me appreciate the life of the artist much more; I really prefer being a musician.”

Corporate life over, he and Ross hunkered down for this latest trilogy, “a reflection on the way we are now in the world we live in now,” Ross says, “and the scary things in America. A dark journey.” For Reznor, the records started “from this position of: I think I know who I am now, the chaos feels behind me, there’s family life and stability. It was me daring myself to say: ‘What if all that was bullshit? And what I really am is an addict in remission that can’t wait to light a match to the whole thing?’” Aside from this flirtation with the devil, he and Ross describe it as a reflection on Trump’s America. “It feels like things are coming unhinged, socially and culturally,” says Reznor. “The rise of Trumpism, of tribalism; the celebration of stupidity. I’m ashamed, on a world stage, at what we must look like as a culture. It’s seeing life through the eyes of having four small kids – what are they coming into? And who am I in this world where it feels like every day the furniture got moved a bit while I slept?”

The first EP, Not the Actual Events, was a “self-destruct fantasy binge” that harked back to NIN’s 90s sound; the second, Add Violence, “was addressing the same issue, but saying: ‘Maybe it’s not me, maybe it’s the world, maybe this is all a simulation.’” Bad Witch came from a realisation that it is all our fault, after all: “We aren’t these enlightened beings, here to take care of each other and think about our benevolent role in the universe as protectors and creators – we’re just a fucking mutation and an accident.” For Reznor, it wasn’t merely Trump’s presidency that brought on this Damascene moment – it was our online behaviour. “We’ve got dumber, more tribalised; we’ve found niches of other people that focus on extremity. For the miracle of everyone sharing ideas, I see a hell of a lot more racism. It doesn’t feel like we’ve advanced. I think you’re seeing the fall of the empire of America in real time, before your eyes; the internet has eroded the fabric of decency in our civilisation.” Social media meanwhile is “poisonous: I don’t think great art comes from being overly concerned or hyper-aware of what your audience’s expectations are. Market your brand: that’s part of what being an artist is, sadly.” You can see why he left Apple.

The other thing that gets both barrels today is popular culture. Reznor starts talking up the greatness of Childish Gambino’s This Is America: “Choreography: excellent. Camerawork: excellent. What’s actually being said: I’m really thinking about it. I feel humbled by that – it reminded me that the bar can be as high as it needs to be.” I suggest that one of the best things about it was everyone’s evident joy at parsing its meaning online; I love rap trio Migos, but This is America was a reminder that we cannot live on escapist lyrics alone. “That would sum up my cursory feelings on popular culture right now,” he replies. “There’s plenty of birthday cake, Migos being a great example – there’s nothing wrong with that. But isn’t there anything else? There are times I don’t mind being reminded of excellence.”

While he admits that his alienation from pop culture might be down to his age, he suggests that he would like as many thinkpieces devoted to rock – presumably including him – as there are about hip-hop. “How many Kanye West thinkpieces have the Guardian done in the last fucking month?” he asks. Er, a few. “The guy’s lost his fucking mind: that’s the thinkpiece. His record sucked, and that’s it. He has made great shit; he’s not in a great place right now.” So you’d like the conversation to be wider? “It would be nice, but there’s no appetite.”

Later, on stage, Reznor shows that Nine Inch Nails are still worth talking about. Holding the mic as if he’s turned a lightsaber on himself, he vents half a lifetime of political anger and personal revelation into it. “It’s not coming from the same place as when I was 23 years old, but there is still rage,” he’d said earlier. Nine Inch Nails’ genius is to create a pit to contain that rage, and the audience’s too. While the lights initially face the band, they slowly rotate during the show until they are facing out into the crowd: a small gesture of communion in Trump’s America. Maybe it is not all cold and black and infinite after all.

Bad Witch is released on 22 June in the UK. Nine Inch Nails play Royal Festival Hall, London, on 22 June as part of Robert Smith’s Meltdown, and Royal Albert Hall, London, on 24 June.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion